No, Pandemic UI didn't kill jobs

Mulligan and Moore are at it again...

Bad economic arguments can be like the aliens in one of those old Space Invaders games. No matter how many you shoot down, they just keep coming. So you have to just keep shooting.

Casey Mulligan and Stephen Moore are two economists who will never, ever give up the idea that when government gives people anything, for any reason, it kills jobs. Moore, a one-time Trump advisor, has made a name for himself by simply repeating that tax cuts help the economy. In the service of this claim, he’s made a list of howlers so long it’s hard to identify them all. Mulligan wrote a book called “The Redistribution Recession”, claiming that food stamps, unemployment insurance, and Medicaid were a major reason for the Great Recession — in other words, that unemployment was high because people were taking a government-sponsored vacation. In 2014, he predicted that Obamacare would lead to a substantial decrease in full-time employment relative to part-time employment. That prediction didn’t exactly work out, as a glance at the ratio of full-time to part-time workers will show:

Anyway, I could go on rehashing the past all day, but the point is, it’s not even one tiny bit surprising to see Mulligan and Moore claim, in the pages of the Wall Street Journal, that Pandemic UI killed millions of jobs. Pandemic UI, remember, was the $600/week extra unemployment benefit that Steve Mnuchin and Congress worked to create back at the end of March as part of the CARES Act. That program is widely credited with helping to decrease poverty and boost consumption during the early stages of the pandemic.

But Mulligan and Moore write:

In July we warned on these pages that six more months of $600-a-week bonus unemployment benefits would keep millions of Americans out of the workforce...President Trump didn’t fully suspend bonus benefits—which would have been optimal for job growth—but he did cut them to $300 a week. Americans subsequently rushed to fill jobs and the unemployment rate fall rapidly...We estimate that Mr. Trump saved between three million and five million jobs by refusing to cave in to Democratic demands for six more months of supplemental benefits.

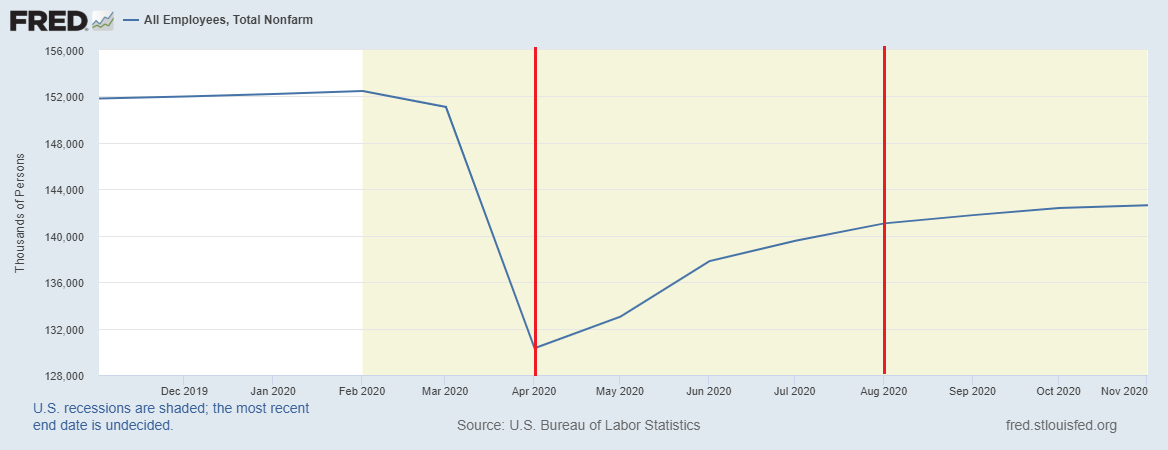

That’s a startling claim, given that employment increased after Pandemic UI was passed, and that the rate of increase slowed after Pandemic UI expired:

But of course, it’s technically possible that without Pandemic UI, employment would have increased by even more from April through July, and that if Pandemic UI had continued, employment would have fallen again in August. This is insanely unlikely, but we can’t rule it out just by looking at this one graph! So let’s look at some more detailed evidence.

First, there’s this paper by Altonji et al. from late July, which uses private employment data along with individual differences in the percent of a worker’s wages that Pandemic UI replaced (called the “replacement rate”), in order to measure the effect of Pandemic UI on employment. Their results are unambiguous:

We test whether changes in UI benefit generosity are associated with decreased employment, both at the onset of the benefits expansion and as businesses look to reopen. We use weekly data from Homebase, a private firm that provides scheduling and time clock software to small businesses, which allows us to exploit high-frequency changes in state and federal policies to understand how firms and workers respond to policy changes in real time. Additionally, we benchmark our results from the Homebase data to employment outcomes in the Current Population Survey (CPS). We find that that the workers who experienced larger increases in UI generosity did not experience larger declines in employment when the benefits expansion went into effect. Additionally, we find that workers facing larger expansions in UI benefits have returned to their previous jobs over time at similar rates as others. We find no evidence that more generous benefits disincentivized work either at the onset of the expansion or as firms looked to return to business over time.

(emphasis mine)

Other papers by Bartik et al. and Dube et al., using different data sources, find exactly the same result. And Ernie Tedeschi has a research note finding the same.

OK, so what evidence do Mulligan and Moore have to counter this mountain of careful empirical evidence? Their only actual piece of data is the fact that job openings fell during Pandemic UI and rose after Pandemic UI expired:

Bureau of Labor Statistics data show that from May through July—when unemployment benefits were high—job openings surged. As the Journal reported, employers complained they were having trouble rehiring workers.

Once the high benefits expired in August, job openings fell for the first time since the start of the pandemic. This certainly wasn’t because the economy was faltering. Third-quarter gross domestic product surged at a 33% annualized rate.

But it makes no sense to look at job openings without actually looking at employment. Mulligan and Moore note that job openings fell in August, but looking at the graph of employment above, it’s obvious that the fall was NOT because employment surged! In other words, job openings didn’t fall because a bunch of people became willing to work after Pandemic UI was cut off; they fell for some other reason.

As for the increase in job openings under Pandemic UI, the story is not quite what Mulligan and Moore claim. Pandemic UI went into effect at the end of March and job openings continued to plunge in April. Here, from a paper by Marinescu et al., is a picture of job vacancy postings using high-frequency private data:

The timing of the increase in vacancies — which began in mid-May, over a month after Pandemic UI started — just doesn’t like up with Mulligan and Moore’s story.

Marinescu et al. also look at applications per vacancy — in other words, how hard people are trying to get jobs. If Mulligan and Moore were right, this number would go DOWN under Pandemic UI, due to people being less willing to work. Instead, Marinescu et al. find that it went UP:

In other words, under Pandemic UI, Americans actually tried harder to get jobs.

So there are at least four careful, high-quality academic papers that just blow Mulligan and Moore’s argument right out of the water. What scraps of evidence they muster are not the kind of thing required to prove their case, and don’t even fit their story anyway.

Mulligan and Moore are just wrong.

At this point a few of you might be asking: How the heck could they be wrong? How can you pay people not to work, and pay them more than they’d earn at a job, and NOT see workers drop out of the workforce and take the checks instead?

The best answer comes from this paper by Boar and Mongey (a great example of how macroeconomic theory can help us think through questions like this). They explain that when deciding whether to work or to collect government checks, workers don’t just care about how much money they’ll get next month; they care about how much money they’ll be able to get six months or a year or two years from now. Jobs are hard to find, and coming back to work after a period of unemployment can also mean your wages take a big hit. So it’s generally better to hang onto a job if you can, even if that means a little less money for a few months.

Combine that with the stimulative effects of Pandemic UI — that consumption increase I mentioned earlier — and it’s entirely possible that Pandemic UI had no negative effect on employment at all. Or even a slight positive effect!

Of course, that leaves open the possibility that if Pandemic UI had been extended through the end of 2020, a few workers would have decided that it was permanent, and would have started dropping out of the workforce in late summer or fall. That possibility can’t be ruled out. And an actually permanent version of Pandemic UI almost certainly would reduce employment by a substantial amount.

But that’s not what happened. What happened is that the government gave unemployed people a bunch of money in a time of need, and they used that money to avoid poverty, and they kept trying to get jobs, and the people who still had jobs didn’t quit those jobs in order to sit on the couch and collect checks. The program was a success, and the arguments of the naysayers don’t really have a leg to stand on.

____________________________________________________________________________

(By the way, remember that if you like this blog, you can subscribe here! There’s a free email list and a paid subscription too!)

What do you expect from a man who thinks child labor is perfectly fine (Moore). The man is a moral cretin.

Is there a worse pretend-economist out there than Stephen Moore? He's got to at least be in the running for all-time worst, right?