Elon Musk recently reposted a video showing a montage of drone swarms in China, declaring that the age of manned fighter jets was over:

I’m not sure if Musk is right about the F-35 and other manned fighters — drones and fighters play different roles on the battlefield, and may coexist in the future (for an argument that the F-35 itself has been overly maligned, watch this fun video). But in any case, Musk’s larger point that drones will dominate the battlefield of the future should now be utterly uncontroversial.

Drones have already become the essential infantry weapon, capable of taking out soldiers and tanks alike, as well as the key spotter for artillery fire and the standard method of battlefield reconnaissance. Electronic warfare — using EM signals to jam drones’ communication with their pilots and GPS satellites — is providing some protection against drones for now, but once AI improves to the point where drones are able to navigate on their own, even that defense will be mostly ineffectual. This doesn’t mean drones will be the only weapon of war, but it will be impossible to fight and win a modern war without huge numbers of drones.

And who makes FPV drones, of the type depicted in Musk’s video? China. Although the U.S. still leads in the production of military drones, China’s DJI and other manufacturers dominate the much larger market for commercial drones:

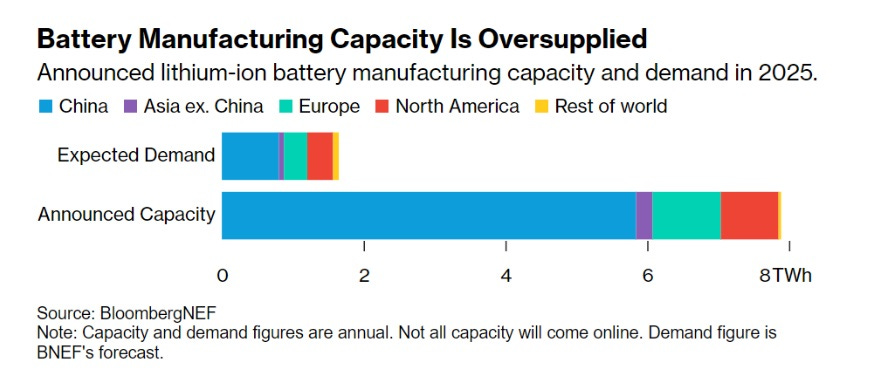

And one absolutely essential component of an FPV drone is a battery. In fact, improvements in batteries — along with better magnets for motors and various kinds of computer chips for sensing and control — are what enabled the drone revolution in the first place. And who makes the batteries? That would also be China:

So now I want you to imagine what happens if the U.S. and its allies get in a major war with China — as analysts say is increasingly possible. In the first few weeks, much the two countries’ stores of munitions — including drones and the batteries that power drones — will be used up. After that, as in Ukraine, it will come down to who can produce more munitions and get them to the battlefield in time.1

At that point, what will the U.S. do if neither we nor our allies can make munitions in large numbers? We will have to choose to either 1) escalate to nuclear war, or 2) lose the war to China. Those will be our only options. Either way, the U.S. and its allies will lose.

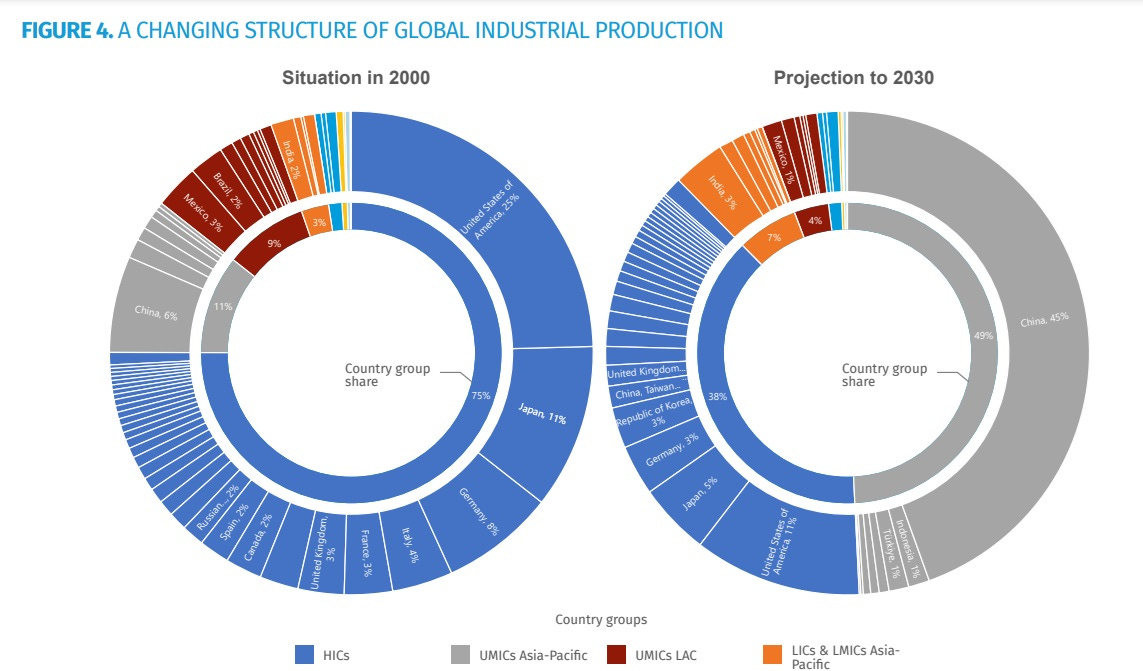

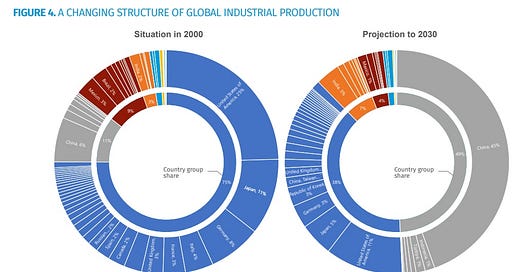

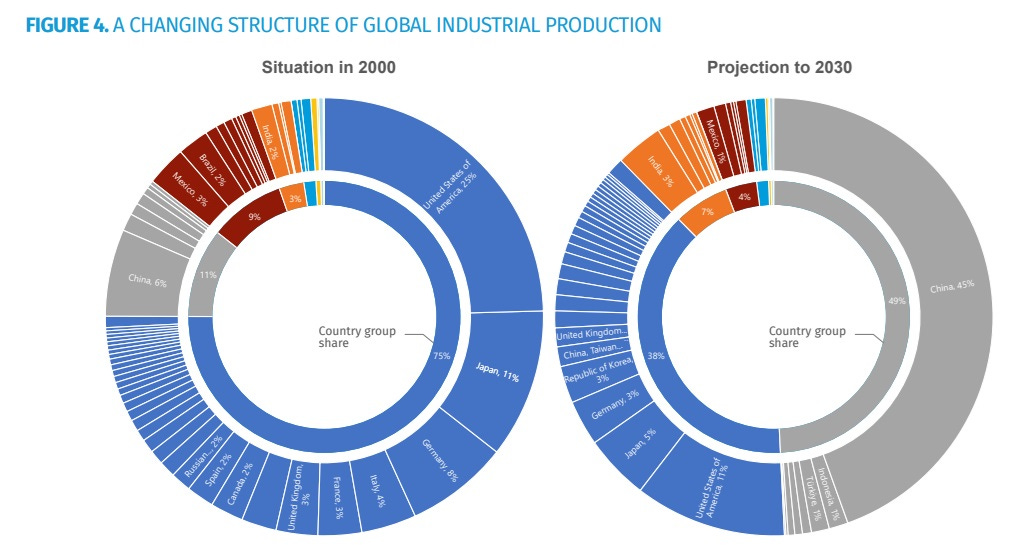

Now realize that the U.S. and its allies aren’t just falling behind China in drone and battery manufacturing — we’re falling behind in all kinds of manufacturing. The chart at the top of this post comes a 2024 report by UNIDO, the United Nations Industrial Development Organization. Here, let me repost it so we can take a look:

In the year 2000, the United States and its allies in Asia, Europe, and Latin America accounted for the overwhelming majority of global industrial production, with China at just 6% even after two decades of rapid growth. Just thirty year later, UNIDO projects that China will account for 45% of all global manufacturing, singlehandedly matching or outmatching the U.S. and all of its allies. This is a level of manufacturing dominance by a single country seen only twice before in world history — by the UK at the start of the Industrial Revolution, and by the U.S. just after World War 2. It means that in an extended war of production, there is no guarantee that the entire world united could defeat China alone.

That is a very dangerous and unstable situation. If it comes to pass, it will mean that China is basically free to start any conventional conflict it wants, without worrying that it will be ganged up on — because there will be no possible gang big enough to beat it. The only thing they’ll have to fear is nuclear weapons.

And of course other nations will know this in advance, so in any conflict that’s not absolutely existential, most of them will probably make the rational choice to give China whatever it wants without fighting.2 China wants to conquer Taiwan and claim the entire South China Sea? Fine, go ahead. China wants to take Arunachal Pradesh from India and Okinawa from Japan? All yours, sir. China wants to make Japan and Europe sign “unequal treaties” as revenge for the ones China was made to sign in the 19th century? Absolutely. China wants preferential access to the world’s minerals, fossil fuels, and food supplies? Go ahead. And so on.

China’s leaders know this very well, of course, which is why they are unleashing a massive and unprecedented amount of industrial policy spending — in the form of cheap bank loans, tax credits, and direct subsidies — to raise production in militarily useful manufacturing industries like autos, batteries, electronics, chemicals, ships, aircraft, drones, and foundational semiconductors. This doesn’t just raise Chinese production — it also creates a flood of overcapacity that spills out into global markets and forces American, European, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese companies out of the market.

By creating overcapacity, China is forcibly deindustrializing every single one of its geopolitical rivals. Yes, this reduces profit for Chinese companies, but profit is not the goal of war.

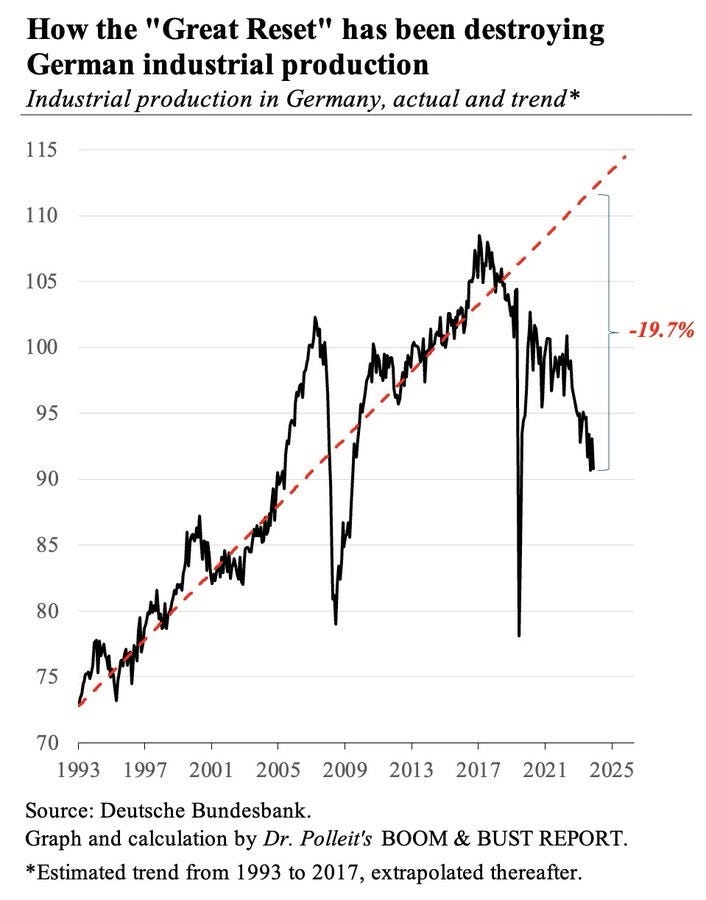

America’s most economically important allies — Germany and Japan — are bearing the brunt of China’s most recent industrial assault. In the 2000s and 2010s, Germany’s manufacturing exports boomed, as they sold China high-tech machinery and components. China has now copied, stole, or reinvented much of Germany’s technology, and are now squeezing out the Germany suppliers:

This is one reason — though not the only reason — why German industrial production has been collapsing since 2017:

Meanwhile, China has already taken away much of the electronics industry from Japan, and now a flood of cheap Chinese car exports is demolishing the vaunted Japanese auto industry in world markets:

The democratic countries have all struggled to respond to China’s industrial assault, because as capitalist countries, they naturally think about manufacturing mainly in terms of economic efficiency and profits unless a major war is actively in progress.

Democratic countries’ economies are mainly set up as free market economies with redistribution, because this is what maximizes living standards in peacetime. In a free market economy, if a foreign country wants to sell you cheap cars, you let them do it, and you allocate your own productive resources to something more profitable instead. If China is willing to sell you brand-new electric vehicles for $10,000, why should you turn them down? Just make B2B SaaS and advertising platforms and chat apps, sell them for a high profit margin, and drive a Chinese car.

Except then a war comes, and suddenly you find that B2B SaaS and advertising platforms and chat apps aren’t very useful for defending your freedoms. Oops! The right time to worry about manufacturing would have been years before the war, except you weren’t able to anticipate and prepare for the future. Manufacturing doesn’t just support war — in a very real way, it’s a war in and of itself.

Democratic countries seem to still mostly be in “peace mode” with respect to their economic models. They don’t yet see manufacturing as something that needs to be preserved and expanded in peacetime in order to be ready for the increasing likelihood of a major war. Fortunately, both Republicans and Democrats in America have inched away from this deadly complacency in recent years. But both the tariffs embraced by the GOP and the industrial policies pioneered by the Dems are only partial solutions, lacking key pieces of a military-industrial strategy.

Neither Republicans nor Democrats have a complete strategy for winning the manufacturing war

A military-industrial strategy for the U.S. and its allies to match China will need to involve three elements:

Tariffs and other trade barriers against China, in order to prevent sudden floods of Chinese exports from forcibly deindustrializing other countries.

Industrial policy, to maintain and extend manufacturing capacity in democratic nations.

A large common market outside of China, so that non-Chinese manufacturers can gain economies of scale.

The GOP’s tariffs-first approach achieves the first of these, but actively sabotages the third by putting tariffs on allies. The Democrats’ industrial policy focused approach achieves the second, but hamstrings much of its own effort with regulation and contracting requirements.

First, let’s talk about the GOP, since Trump is about to come back into office. In his first term, Trump moved the U.S. away from the free trade consensus and from the model of “engagement” with China. He pioneered the use of both tariffs and export controls as economic weapons. In his second term, he’s almost certain to double down on tariffs.

This will help protect the remaining pieces of U.S. industry from being suddenly annihilated by a wave of subsidized Chinese imports — as happened to the U.S. solar panel industry in the 2010s. But Trump is making a number of mistakes that will severely limit the effectiveness of his tariffs.

First, he’s threatening broad tariffs on most or all Chinese goods, instead of tariffs targeted at specific, militarily useful goods. In a post two weeks ago, I explained why broad tariffs are of limited effectiveness:

Broad tariffs cause bigger exchange rate movements, which cancel out more of the effect of the tariffs. Putting tariffs on Chinese-made TVs, clothing, furniture, and laptops weakens the effect of tariffs on Chinese-made cars, chips, machinery, and batteries.

Second, Trump is threatening to put tariffs on U.S. allies like Canada and Mexico. This will deprive American manufacturers of the cheap parts and components they need to build things cheaply, thus making them less competitive against their Chinese rivals. It will also provoke retaliation from allies, limiting the markets available to American manufacturers.

As for industrial policy, Trump doesn’t seem to see the value in it. He has threatened to cancel the CHIPS Act, as well as the Inflation Reduction Act that subsidizes battery manufacturing. But tariffs cannot simply make chip and battery factories sprout from American soil like mushrooms after the rain. Tariffs protect the domestic market but do absolutely nothing to help American manufacturers in the far larger global market; only industrial policy can do that.

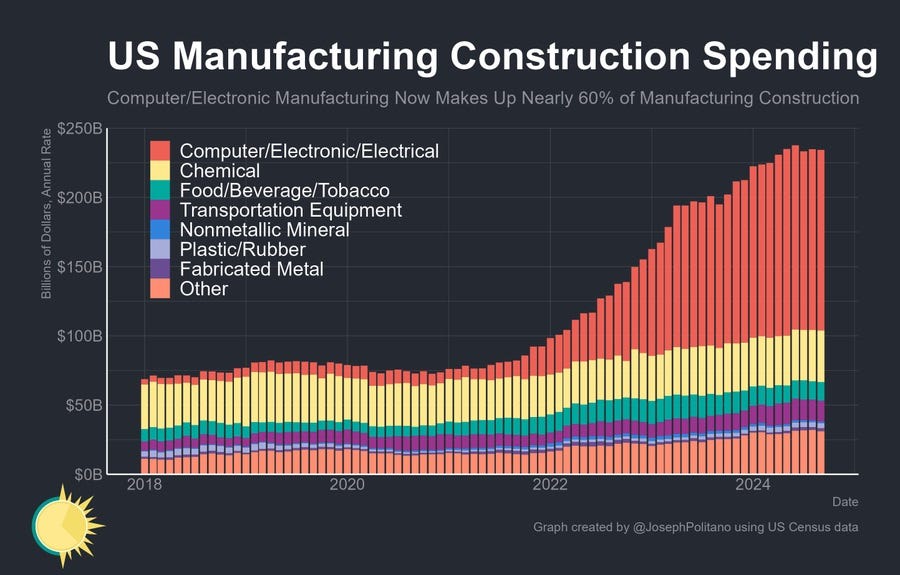

Democrats do support industrial policy. And in fact, Biden’s industrial policies have been one of the few small successes that any democratic nation has had in the struggle to keep up with China’s manufacturing juggernaut. A bonanza of factory construction is now taking place in the U.S.:

The construction is heavily concentrated in the industries Biden subsidized, even though almost all of the actual money being spent is private.

This is great, but the effort has been slowed by progressive policy priorities. Stubborn progressive defenses of NEPA and the American permitting regime have prevented major reform of that formidable stumbling block, while various onerous contracting requirements — the dreaded “everything bagel” — have held up construction timelines.

Even more fundamentally, progressives tend to see the point of industrial policy as providing jobs for factory workers, rather than in terms of national defense. This tends to make them complacent about delays and cost overruns, since these end up providing more jobs even as they prevent anything physical from actually getting built:

This is also why some progressives oppose automation in the manufacturing sector, on the grounds that it kills jobs. China, meanwhile, is racing ahead with automation, having recently zoomed ahead of both Japan and Germany in terms of the number of robots per worker, and leaving America in the dust:

Meanwhile, although Democrats may become negatively polarized into opposing all tariffs (throwing the baby out with the bathwater), they still oppose measures like the TPP aimed at creating a common market capable of balancing China’s internal market.

In other words, neither political party in America has yet grasped the nature or the magnitude of the challenge posed by China’s manufacturing might, or the nature of the steps needed to respond. Trump is still dreaming the same simple protectionist dreams he thought of back in the 1990s, while his progressive opponents think of reindustrialization as a giant make-work program. Meanwhile, America’s allies overseas seem even less capable of averting their decline.

The manufacturing war is being lost, and we urgently need to turn things around.

Of course those munitions will have to be roughly equal in quality, but it’s pretty obvious that China is now technologically on par with other major nations in almost every area.

Insert overused Sun Tzu quote here.

Speaking of economic wars: In solar power systems, essentially all of the smart electronic boxes (inverter/controller/battery management/etc.) are manufactured in China. US brands are almost entirely contract manufactured, and typically OEM rebrands of a Chinese design with some amount of customization. This is especially true of the current devices of choice for private and small business solar installations: The AIO (all in one) box, which simplifies installation, operation, and monitoring. The main EG4 (Texas) AIO, for instance, is a rebrand of a Luxpower (China) product, the (Chinese) Deye inverters are rebranded for Sol-Arc, sold in the northern US and central America, called Sunsync and sold in the EU, called inverex and sold in Pakistan and so on and so forth.

The Chinese are not interested in the competition between these rebrands -- each is given a region and a monopoly for what is sold there. There has been speculation and concern that such China-manufactured products may contain a backdoor to allow remote shutdown, which could be used to cripple both the US electrical grid and stand-alone solar powered sites should relations with China sour into open or cold war. People who have worried have been told that they are racist, fear-mongering conspiracy theorists for having such ideas, because of Climate Change.

Well, on November 15, the tin hats have been proven correct once again, at least in terms of Deye products. Deye "bricked" a number of Deye-branded AIO inverters, mainly in Puerto Rico, but some reported in the US, Canada, Pakistan and Costa Rica.

The inverters were shut down and displayed the following message:

This inverter is not allowed use at Pakistan/USA/UK

Pakistan contact inverex

USA contact Sol-Arc

EU contact Sunsync

Pls return to your supplier.

The following page requires a 5 digit passcode to start This passcode is generated overseas

Please have your passcode ready. [PROCEED]

So if you got the message in error, you could in theory get your inverter to start again. Otherwise you have a nice brick. This appears to be response to a Sol-Arc suit claiming Deye was not doing enough to stop dealers from selling Deye-branded versions of their inverters in their contracted exclusive territories, but you cannot rule out a Chinese cyberwar limited trial shot after the Trump election, preparing for conflict with the US, with the above as a cover story.

It's been two weeks and nobody has reported receiving any passcodes so far.

Discussion thread here in the DYI solar forum. There are thousands of messages but not a lot more information than what I posted here.

https://diysolarforum.com/threads/china-kills-all-non-sol-ark-branded-deye-unit-in-the-usa-this-morning.94349/

Absolutely brilliat. Clarifies and deepens the argument I and advanced manufacturing colleagues are championing in the UK. Thank you