Ed Prescott, who was in some ways the father of modern macroeconomics, passed away recently at the age of 81. I thought this would be a good idea to write about the state of macro as a science. I used to write about this a lot when I first started blogging, so it’s a fun topic to revisit.

Macroeconomics has a bad reputation. I often see people whom I like and respect say stuff like this about the field of economics:

When they say this, I’m pretty sure they aren’t talking about the auction theorists whose models allowed Google to generate almost all of its ad revenue. And I’m pretty sure they aren’t talking about the matching theorists whose models improved kidney donation and saved countless lives. When people say “economists are still struggling to predict the last recession”, they’re talking about macroeconomists — the branch of econ that deals with big things like recessions, inflation, and growth.

It isn’t just pundits and commentators who are annoyed with the state of macro; economists in other fields often join in the criticism. For example, here’s Dan Hamermesh in 2011:

The economics profession is not in disrepute. Macroeconomics is in disrepute. The micro stuff that people like myself and most of us do has contributed tremendously and continues to contribute. Our thoughts have had enormous influence. It just happens that macroeconomics, firstly, has been done terribly and, secondly, in terms of academic macroeconomics, these guys are absolutely useless, most of them. Ask your brother-in-law. I’m sure he thinks, as do 90% of us, that most of what the macro guys do in academia is just worthless rubbish.

This is much harsher than I would put it, but it hints at some of the vicious internal battles being waged in the ivory tower. And even top macroeconomists are often quite upset at their field — see Paul Romer’s (extremely nerdy) 2015 broadside, “Mathiness in the Theory of Economic Growth”.

Ed Prescott’s generation of macroeconomists came into the field intent on fixing this situation.

Prescott’s solution and the DSGE Revolution

The stagflation of the 1970s had called into question much of the conventional wisdom in the field, and academics were scrambling to both diagnose the problem and offer solutions. Prescott’s idea turned out to be the most revolutionary and impactful. In 1982, he and Finn Kydland published a paper modestly titled “Time to Build and Aggregate Fluctuations”, which was actually a grand theory of why economies have booms and busts.

That theory came to be known as “Real Business Cycle Theory”, and it won Kydland and Prescott a Nobel prize in 2004. The basic idea was that booms and busts are driven by changes in the rate of productivity growth. Recessions, in this theory, happen when something temporarily reduces the rate of productivity growth — a decline in the rate of new innovations, or a deterioration in the terms of trade, or an ill-advised tax policy, etc. These slowdowns reduce the demand for labor, which reduces wages, which makes some people decide to take off of work for a while — hence unemployment. According to these models, demand-boosting policy like interest rate cuts, quantitative easing, or fiscal stimulus has no hope of boosting growth or reducing unemployment, since these policies don’t increase the speed of technological progress. These policies, Prescott declared, are “as effective in bringing prosperity as rain dancing is in bringing rain”.

If Prescott’s story — recessions happening because engineers just didn’t invent as much stuff this year, unemployment as a voluntary vacation — sounds highly implausible to you, it’s because it is highly implausible. A vigorous pushback against RBC models began the moment they came out. The most famous early salvo came from none other than Larry Summers, who pointed out that many of the parameter values in Prescott’s model — numbers that were treated as akin to constants of the Universe — didn’t make a lot of sense.

In fact, those weren’t the only things that were mathematically suspect about RBC — the procedure Prescott used to separate economic “fluctuations” from changes in long-term growth, for example, was highly unreliable. And the way that RBC theorists “validated” their models — by creating simulations of the economy, eyeballing those simulations, and then declaring that the size and frequency of the fluctuations looked similar enough to the real economy — was an incredibly low bar for any model to clear. A cottage industry sprang up in the macroeconomics field showing all the ways that RBC models failed to fit the data. Wonkier papers showed that small, plausible extensions of the model turned the basic results on their head.

All this led to RBC falling out of fashion among macroeconomists. Though Prescott and a few allies continued to insist that RBC models were a good description of the macroeconomy — and briefly attempted to extend it to other economic phenomena — at this point very few macroeconomists use it as anything other than a teaching device.

And yet despite all these issues, RBC still won the day. Why? Because the modeling methods that Prescott pioneered became so influential that they basically took over the entire macroeconomics field. RBC pioneered a type of modeling called “Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium” that became the standard tool in macro theory.

A little background here for the uninitiated. If you’re trying to analyze the whole economy at once, you quickly run into the problem that everything affects everything else. Before Prescott, the most common ways to deal with this were A) to basically make a giant spreadsheet of correlations between different sectors of the economy, and hope and pray (er, “assume”) that those correlations would hold when there was some kind of policy change, or B) to make simple toy models that were basically a couple of equations or a few lines on a graph, and then use these to make vague, qualitative predictions. Both approaches were deeply unsatisfying — (A) because no one really believed the correlations in the giant spreadsheet were robust, and (B) because you couldn’t really test these vague little theories, and because they were kind of simple and undergrad-ish.

So Prescott and his allies turned to a theory called general equilibrium, which is basically just a gigantic supply-and-demand model that tries to model every transaction in the entire economy at the same time. If that sounds really hard, it’s because it is really hard — so hard, in fact, that to actually make general equilibrium usable, you have to make an incredible amount of simplifying assumptions. Those assumptions are generally so unrealistic that economists in most fields besides macro — for example, public economics, which deals with taxes and spending — have drifted away from using general equilibrium:

But in macro, general equilibrium won the day. Though RBC models fell out of style, they were replaced by a different class of models called New Keynesian models that used the same basic mathematical framework Prescott had pioneered. New Keynesian models make different assumptions about how the economy works — most importantly, they leave a role for monetary and fiscal policy to fight recessions. But math-wise, the bones of New Keynesian models are pretty much the same as RBC.

And that’s the real reason Prescott and Kydland won their Nobel. The economics prize tends to be a prize for developing new methods rather than for making concrete discoveries about the world. This sort of makes sense for a new science — before you can start finding the facts, you have to develop tools for finding the facts, so it’s reasonable to reward people who develop new tools.

The problem with this approach is that sometimes the new tools are influential but don’t actually work very well when applied to the real economy. And that’s basically what has happened with DSGE models so far.

DSGE and its discontents

DSGE models boil a great big complicated economy down to just a few things — consumption, productivity, hours worked, and so on. To many economists, this parsimony is an advantage. But it requires huge simplifying assumptions in order to make it work. The assumptions of New Keynesian models are a heck of a lot more realistic than those of their RBC predecessors, but that’s a very relative statement. In a post back in 2013, I took a standard, popular DSGE model and made a partial list of its assumptions. Most of them bore very little relationship to reality. For example:

Firms can only change their prices at random times…This is "Calvo pricing"…The wage demanded by households is also subject to Calvo pricing (i.e. it can only be changed at random times). Households purchase financial securities whose payoffs depend on whether the household is able to reoptimize its wage decision or not. Because they purchase these odd financial assets, all households have the same amount of of consumption and asset holdings.

This is obvious fantasy. Have you ever heard of a financial asset that pays off depending on whether or not you’re able to renegotiate your wage this year? No, because no such asset exists. Other assumptions are just provably false when you look at the micro evidence — a fact that was pointed out to me by one of the creators of the model described above.

Why would macroeconomists base their models on obvious fantasies and known falsehoods? Well, one reason is because it makes the math “tractable”. Macroeconomists want their math hard enough to make them look smarter than sociologists, but not too hard that they can’t get clean-looking solutions. DSGE hit that goldilocks point.

Macroeconomists who do this kind of modeling will sometimes defend themselves by making reference to Milton Friedman’s famous “pool player analogy”. This is the idea that a pool player doesn’t have to know all the physics and physiology of how they hit the ball — they just have to know how to hit a ball, and their body does the rest. In economics, this principle means that as long as models can match the macro data — the overall fluctuations of employment, growth, etc. — then the building blocks of the model don’t have to match the micro data.

It’s a pretty weak defense, though, for a number of reasons. First, it violates something called the Lucas Critique — if the “microfoundations” of a macro model aren’t actually based on reality, then the model could just break down and stop working as soon as you try to use it. Second, there just isn’t that much macroeconomic data out there.

That’s a weird claim to make, right? We’ve been keeping track of macro data every month, for many decades now, for a variety of different countries. But most of those data points are highly dependent on each other — if unemployment is high one month, it’s likely to be high the next month. And when the U.S. economy crashed in 2008, the German economy and the Japanese economy suffered as well. So the actual amount of information we have is pretty small.

Statisticians Daniel J. McDonald and Cosma Shalizi have been studying DSGE models for a while now, and have just come out with a pretty damning paper. They simulated the most popular models — Prescott’s original RBC, and the most widely used modern New Keynsian model — and found that even if the models’ assumptions were all exactly right, it would take thousands of years of data to learn the correct parameter values.

(Update: A number of people are claiming that McDonald & Shalizi’s first result doesn’t replicate. So I guess we have to wait and see about that. But to be honest, I just cited this paper because it’s recent and kind of fun; the difficulty of estimating modern DSGE models is already very well-known.)

But it gets even worse. McDonald and Shalizi also try fitting DSGE models to nonsense data. They replace unemployment with consumption, consumption with productivity, etc. — in other words, a complete nonsense economy. And they find that DSGE models fit this nonsense data just about as well — or in some cases, even better — than they fit the data of the real economy. In other words, any apparent match between these macroeconomic models and empirical data is probably a coincidence.

Unsurprisingly, DSGE models are also really bad at forecasting the economy — worse, in many cases, than the simplest imaginable models (called univariate AR(1) models).

So if they don’t fit the data and they can’t forecast the economy, what can DSGE models actually do? For private-sector companies, the answer is “nothing” — every attempt to use DSGE models for finance or other practical applications has come to naught. But for policymakers, the answer is increasingly also “nothing”. During the 2008 crisis and the recession that followed, central bankers found that DSGE models were too cumbersome and unintuitive to give them quick answers — instead, they found themselves turning back to the ultra-simple, qualitative models they had used in the distant past. The Fed also continued to use its giant spreadsheets of correlations.

In other words, DSGE — the big innovation in macroeconomic theory over the past 40 years — has so far not proven itself useful for anything other than publishing more econ papers.

Macroeconomists sometimes defend this unfortunate result by saying “all models are wrong” (a quote from statistician George Box), or “it takes a model to beat a model”. But there are plenty of simple models available, which are much easier to understand and use, and which certainly don’t perform any worse than DSGE models in any empirical sense.

A few macro papers do employ some of these alternatives, but most continue to use DSGE. Why? For some, it’s simply because DSGE has become a sort of universal language that macroeconomists use to speak to each other. For others, it’s a way to prove that they have some math chops. And still others earnestly believe that eventually the assumptions that go into DSGE models can be improved so that they’ll fulfill their initial promise and become truly scientific models of the economy.

Personally, I am not so optimistic. But given that the problems with DSGE come from very deep facts about the macroeconomy — the sheer complexity that requires a ton of simplifying assumptions, the lack of good data — I don’t think any clearly better paradigm is going to suddenly appear. This is still a field that’s in its infancy. Modeling a whole economy is a hell of a lot harder of a task than modeling some Google auctions or kidney donations, and there’s every reason to expect true understanding to take some time. Maybe a very long time.

And in the meantime, modeling the economy isn’t the only thing macroeconomists do — they also try to figure out more about how the pieces of the economy work. Here there seems like much more room for progress.

Proto-scientists vs. slick salesmen

Young macroeconomists, generally speaking, already know pretty much everything I’ve written in this post, and are fairly frustrated with Prescott-style macro modeling. Many of them are spending more and more of their time on humbler, more answerable questions — how consumers decide when to splurge and when to cut back, why businesses decide to invest, how various companies and consumers respond to fiscal stimulus or interest rate hikes, and so on. That means a lot of empirical work.

Empirical work is hard in macro, because everything affects everything else. Data is scarce, and you generally need to make too many assumptions for comfort. But “hard” doesn’t mean “impossible”, and most of the best minds in the field are working on how to mine more nuggets of knowledge from the chaos. For an overview of some of the techniques they’re using, I recommend Emi Nakamura and Jón Steinsson “Identification in Macroeconomics”. (Here’s a fun interview I did with Nakamura earlier this year.)

This is exactly the kind of thing macroeconomists would do if they were simply hard-working, curious, intellectually honest scientists trying to learn more about their world. That doesn’t mean macro is a “science” yet — I’d say it’s more a proto-science, maybe a bit like medicine in the 1600s. But there seems to be movement in the right direction.

That isn’t enough for a lot of people, though — especially those in the commentariat, the finance industry, and politics. Most people don’t really know what macroeconomists are up to, or have a firm grasp of the technical challenges involved. And so they become susceptible to the siren song of people who claim to be “heterodox” scholars whose groundbreaking ideas, like Galileo’s, have been suppressed and silenced by the mainstream.

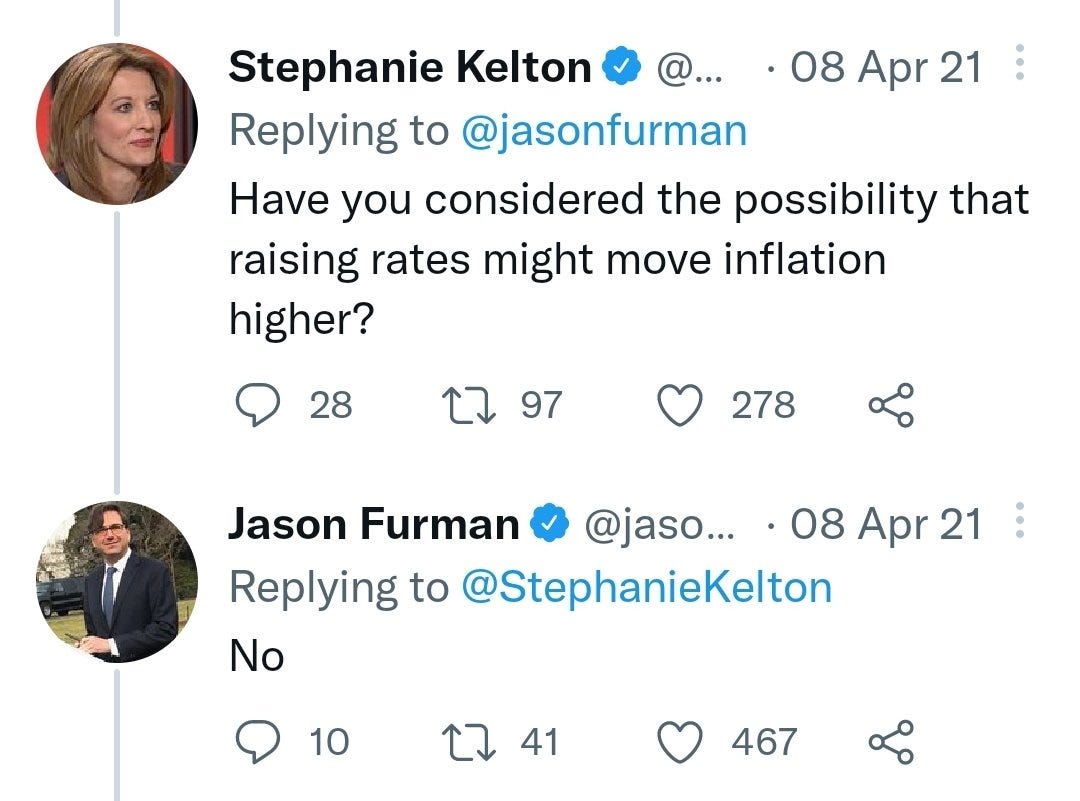

The most famous and most flagrant of these, of course, is MMT. The “T” in MMT stands for “theory”, but there isn’t any actual concrete theory there — instead, it’s defined by memes, and by the pronouncements of a few online gurus. Never revealing the precise details of the theory means never having to say you got anything wrong — which is why the MMT people are constantly taking victory laps, with the help of a few overly credulous journalists. But occasionally they do slip up and make a concrete prediction, and then we get to see how wild the whole enterprise is:

In fact, the theory that low interest rates reduce inflation is now being tested by Turkey, whose president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has embraced the idea expressed by Stephanie Kelton in the tweet above. And how is it going? Well, Turkey now has one of the highest inflation rates on Earth:

But MMT is simply the most egregious example of “heterodox economists” with pretensions of Galileo-hood. There is no shortage of guru-like figures who claim to be able to predict financial crises, but who end up constantly getting the details wrong and predicting 10 crises for every 1 that actually happens.

I don’t want to tar all heterodox economists with this brush, because there are some folks who call themselves by that name who really are doing good work, and whose ideas tend to get explored by the mainstream eventually. But there are a lot of hacks out there, doing their best to be a non-economist’s idea of what an economist looks like. One key giveaway, I think, is that these folks tend to stick to macro, and utterly disdain micro as trivial. This isn’t really because micro is less important — it’s because micro is the area where mainstream economists actually have had a decent amount of predictive success, and where empirical evidence can disprove theories. Slick salesmen of alternative theories prefer to stick to the deep waters where the truth can never really be known.

For all their failures — and for all the overconfidence of the occasional Prescott — mainstream macroeconomists know more about the macroeconomy than do the alternative advice-givers. They are groping their way slowly toward making an actual science of their perpetually disappointed discipline. Sometimes that involves going down blind alleys, backtracking, or hitting dead ends. But anyone who told you this Universe was going to be an easy one to understand was trying to sell you something.

Update: In a Twitter thread, Fabio Ghironi takes issue with some of the phrasing I used in this post. For example, he disagrees with my joke that macroeconomists try to make their math hard in order to distinguish themselves from other fields:

Yes, Ghironi is right about this; I was making a joke, and I should have been clearer about that. Macroeconomists might not mind the “moat” that their math creates around their field, but it’s not intentional; they’re not actually thinking about sociologists at all. The truth, however, is that models with simple math (such as OLG models) don’t seem methodologically innovative compared to posts that pioneer more difficult techniques (like Bayesian estimation or approximate aggregation or projection methods or whatever). It’s the drive for methodological innovation, rather than some kind of chauvinism or obscurantism, that biases the field toward clunky-but-novel math.

He also disagrees with my assessment that DSGE papers haven’t been of practical use:

Ghironi doesn’t elaborate here, but I am going to stick to my guns on this one. DSGE models aren’t good at forecasting, the standard microfoundations have been repeatedly shown to not fit the micro data and are theoretically dubious, the models are very difficult to even fit to the data in the first place, private companies refuse to use the models, and central banks only use them as one source of analysis among many. That doesn’t mean I think it was a mistake to try modeling the economy this way, or that there’s anything obviously better out there. But a scientific theory should have a clear successful use case outside of the realm of thought experiments before we call it a success.

Update 2: Hanno Lustig points out that I criticize Prescott’s modeling approach, but also agree that microfoundations are the best way forward. That is true, and there is no contradiction here. Prescott’s basic idea of basing macro models on micro behavior was good, but the specific way that he tried to implement it was not successful.

Update 3: Scott Sumner argues that macro is not in its infancy but rather is senile, trapped in a failed paradigm. Worth a read.

Update 4: I went on David Beckworth’s Macro Musings podcast to elaborate on the ideas I expressed in this post. Check it out!

IS-LM macro still works well enough. Macro was in a better state in 1958 than it now. https://johnquiggin.com/2013/01/05/the-state-of-macroeconomics-it-all-went-wrong-in-1958/

As for DSGE, you know my view from Zombie Economics.

Do any modern macro economists ever think about Georgism? I’m just in this journey of discovery and it seems fundamentally so necessary. Almost too easy and obvious and I’ve been seeking counter arguments.