"Luxury" construction causes high rents like umbrellas cause rain

The NIMBY mindset persists in the face of evidence.

Imagine if you went outside and saw that it had started to rain, and that people on the street were opening their umbrellas. And imagine that you ran around waving your arms and saying “Stop! Stop! Umbrellas make rain worse!!” People would think you were a silly person, and rightly so.

But why don’t people think that umbrellas make rain worse? After all, everyone knows that rain typically starts to intensify shortly after people start opening their umbrellas. But we have a good causal theory of why rain happens, and we know that umbrellas have nothing to do with it; we know that the umbrellas are a response to the problem, rather than the cause.

The same should be true for market-rate housing construction and rising rents. When a city like Austin, Texas becomes a more important tech hub, lots of high-earning people — managers, engineers, entrepreneurs, venture capitalists — will move into that city for work. And in response, developers will try to build housing that they think the high-earning newcomers will pay a lot of money for. Meanwhile, because a lot of people with money are moving into town, rents go up, making life more expensive for everyone else in the city.

But we don’t think the new construction actually causes rents to go up, right? Because we know that the actual cause of rising rents is the underlying increase in demand. We know that the high-earning people are moving in and pushing up rents because there are economic opportunities to be had in Austin. And we know that the new market-rate housing construction is a response to that rise in demand, rather than the cause, just like umbrellas are a response to rain…right??

Except that a number of people do think that building market-rate housing makes rents go up. This idea is a darling of left-NIMBY activists, for whom ideology and online turf wars generally trump hard-headed empirical evidence. But once in a while I see the idea being taken up by people who write about housing for a living. For example, in a recent article for Bloomberg CityLab entitled “Cities Keep Building Luxury Apartments Almost No One Can Afford”, Prashant Gopal and Patrick Clark write:

Academics, developers and people in their 20s and 30s—particularly those most active on social media—have reached an unusual level of consensus. Their solution, supported by a wealth of scholarly research, is simple and elegant: Loosen regulations, such as zoning, and build more homes of any kind—cheap, modest and palatial.

The shorthand for the movement has become “Build, build, build” or “Yes, in my backyard”—Yimby, for short…

Inconveniently for the Yimbys, Austin, like other cities, is still way more expensive than it was years ago, even though it’s built so many apartments. As a result, a small group of academics is starting to question the free-market path…

Desirable cities around the world have all, one way or another, tried the Austin-style solution to their own housing crises. And they’ve all ended up in a similar bind: urban centers packed with luxury properties that regular folks can’t afford…the very popularity of these places with the affluent drives up housing costs[.]

Now, if you cornered Gopal and Clark — or the “small group of academics” they cite — you could probably get them to admit that if we built 10 market-rate (“luxury”) apartments for every resident of Austin, most of them wouldn’t get filled, and landlords would be forced to slash prices, and regular folks would have cheap apartments to live in. An apartment’s price is not built into its walls and floors; “luxury” is just a marketing buzzword, and most of the apartments that are affordable today went for market rate when they were built.

You could also probably get Gopal and Clark to admit that demolishing every market-rate apartment in Austin would not lead to an affordable city.

But the CityLab writers aren’t thinking in terms of such extreme thought experiments. Instead, they are probably going around and talk to a lot of low-income residents of gentrifying neighborhoods in Austin, and observing that those residents are afraid of all the new nice-looking housing going up. And this probably leads them to suspect that perhaps the YIMBYs are trying to pull one over on the good people of working-class America, who naturally know their own economic interests and are right to be afraid.

Let’s go back to our example of umbrellas and rain, though. It makes perfect sense to worry about rain when you see people opening their umbrellas, even though the umbrellas don’t actually cause the rain. The reason is that when you see a bunch of people opening their umbrellas, it means they’ve probably checked the weather forecast. Umbrellas aren’t a cause of rain, but they are a signal of rain. A harbinger. An omen.

Market-rate housing development is similar. If you’re a working-class person, and you see a big new shiny glass apartment tower going up a block away, it makes perfect sense to be afraid that rents are about to rise. The apartment tower tells you that A) your city is becoming more of an employment hub for yuppie types, and B) for some reason, the yuppie types have decided that your neighborhood is a good one to live in. But that doesn’t mean you think the new apartment tower is the cause of the gentrification.

In fact, it is theoretically possible for new market-rate housing to cause gentrification in the small area surrounding them (unlike umbrellas, which have zero chance of causing rain). It’s possible to imagine that rich newcomers to a city might see shiny glass towers going up in a particular neighborhood and think “Oh my God, that neighborhood is the hot cool new place to be!”, and move there instead of to another part of the city. This is called “induced demand”, and it’s a favorite theory of the academics who decry market-rate housing.

But there’s an obvious problem with this theory. Even if market-rate housing draws rich people to a particular neighborhood, it must be drawing them away from some other neighborhood. Engineers aren’t going to move all across the country from Seattle or San Francisco just because they hear about a new apartment building going up in a particular neighborhood of Austin. If “induced demand” happens, the rich people who flock to a trendy new neighborhood must be coming from another part of Austin. That means that even if new housing did increase rents in one place, it would be reducing them in a different place. If you think about housing policy from the city-wide level instead of just from the vantage point of a single neighborhood — as you definitely should, if you’re a policymaker or a planner — then “induced demand” isn’t scary, because it’s really just relocated demand.

Anyway, whether induced demand is even a big deal in the first place is an empirical question. And the empirics come down pretty firmly on the side of “no”.

The alternative to induced demand is called “filtering” — or as I like to call it, the “yuppie fishtank theory”. Basically, this says that when you build a big glass tower full of nice new apartments, it draws high-earning people away from working-class neigborhoods. Yuppies would probably rather go live in a nice new tower with other yuppies than go around bidding up the price of 40-year-old apartments in working-class neighborhoods. So if you build those “luxury” apartments, they’ll draw the yuppies away and stop them from pricing out the working class.

Gopal and Clark sneer at this theory, calling it “trickle-down economics but for apartments”, even though it bears zero resemblance to the Reagan-era idea of stimulating the economy by cutting taxes. They then turn to the evidence, describinge one empirical paper that supports the “filtering” hypothesis and one that doesn’t:

A growing body of research focusing on cities such as San Francisco and Helsinki has offered support for the filtering effect. Building more apartments, even luxury ones, does indeed moderate prices in surrounding neighborhoods. Older buildings become less attractive; other tenants move in and pay less. In 2019, Brian Asquith and Evan Mast, economists at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research in Kalamazoo, Michigan, concluded that new buildings in low-income areas slow rent growth nearby.

Using similar methods, Anthony Damiano and Chris Frenier, Yimby-skeptical University of Minnesota researchers, also found that new construction reduces rents nearby—but only in upscale buildings and not in a significant way. More important, though, a gentrifying neighborhood drives up the prices of more ordinary units. Overall, they determined in their study of Minneapolis from 2000 to 2018, the new units actually pushed prices up, validating the displacement fears of low-income residents.

What you should notice here is that Gopal and Clark only briefly mention the “growing body of research” that supports the filtering effect, choosing only to specifically name the 2019 paper by Asquith et al. They do not mention Li (2019), who finds that “for every 10% increase in the housing stock, rents decrease 1% and sales prices also decrease within 500 feet.”

Nor do they mention Pennington (2021), who uses a very innovative and credible research design (using structure fires as the spur for new market-rate housing construction), and who finds a decrease in local displacement when new market-rate housing goes up:

I find that rents fall by 2% for parcels within 100m of new construction. Renters’ risk of being displaced to a lower-income neighborhood falls by 17%.

Nor do they mention Mast (2019), who finds that market-rate housing construction reduces rents for the low-income housing market specifically.

Nor do they link to any review of the older literature on this topic, such as the one by Been, Ellen, and O’Regan (2018), who write:

We ultimately conclude, from both theory and empirical evidence, that adding new homes moderates price increases and therefore makes housing more affordable to low- and moderate-income families.

And although they mention that some of the support for “filtering” comes from Helsinki, they do not cite the 2022 paper by Bratu, Harjunen, and Sarimaa. Unlike the papers by Asquith et al., Li, and Pennington, which only study hyperlocal neighborhood effects, Bratu et al. are are able to use Finnish government data — which tracks to tracks where people move from and to — to study how new market-rate housing in one neighborhood affects rents in other neighborhoods. They find that new market-rate construction draws high-income tenants from all over the city, which puts downward pressure on rents all over the place:

We study the city-wide effects of new, centrally-located market-rate housing supply [in] the Helsinki Metropolitan Area. The supply of new market rate units triggers moving chains that quickly reach middle- and low-income neighborhoods and individuals. Thus, new market-rate construction loosens the housing market in middle- and low-income areas even in the short run. Market-rate supply is likely to improve affordability outside the sub-markets where new construction occurs and to benefit low-income people.

Nor do the CityLab writers mention Mense (2020), which finds city-wide rent decreases from construction of new market-rate housing in Germany. You can find these papers in a list maintained by the Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies at UCLA.

Gopal and Clark do mention one study by “Yimby-skeptical” researchers. Damiano and Frenier (2020) use a research design that’s similar to that of Asquith et al. (2019), but find no effect of market-rate housing on overall rents in the area nearby. Breaking down their analysis to look at the effects on the rents of different tiers of nearby housing — something Li (2019) also does — they find that new market-rate housing lowers rents for more expensive nearby apartments, but raises rents for less expensive nearby apartments. This is the opposite of what Li found, which Damiano and Frenier attribute to subtle differences in how the two samples were constructed.

Anyway, I have to say that I’m not a huge fan of the way Gopal and Clark reported on this paper. First of all, identifying Damiano and Frenier as “Yimby-skeptical” impugns their objectivity a bit by defining them in relation to an activist movement, so I’d steer away from that sort of terminology. Second, they fail to note that Damiano and Frenier fail to find an overall effect of new housing on nearby rents overall, and only find an effect on certain sub-markets.

But most importantly, the Damiano and Frenier paper — like the papers by Asquith et al., Li, and Pennington — only studies hyper-local neighborhood effects. The papers that study city-wide effects are pretty much ignored. But shouldn’t city-wide effects matter more? Shouldn’t we make policy at the city level (or the state level), rather than the neighborhood level?

Making policy at the neighborhood level is really the essence of NIMBYism. In a world of hyper-local control, each neighborhood rejects new housing — maybe because they fear gentrification, but more likely because they fear crime, street crowding, property value reduction, or simply any sort of change at all. Each neighborhood’s NIMBYs imagine that all of the country’s necessary new housing will be built somewhere else, in an imaginary HousingBuildyLand far from where they live.

In fact, for a long time we did have a real HousingBuildyLand — it was called the exurbs. Until 2007 our cities sprawled and sprawled and our commutes grew longer and longer. That sprawl belched carbon into the atmosphere and required us to build highways to nowhere, but at least we built housing. Then we hit the limits of how far out from the centers of commerce and industry we could build, and, well, we stopped building as much as we used to:

Ultimately, people need somewhere to live. And if every neighborhood gets to say “not in my back yard”, then there will simply be nowhere to put the housing, and housing will get more expensive overall.

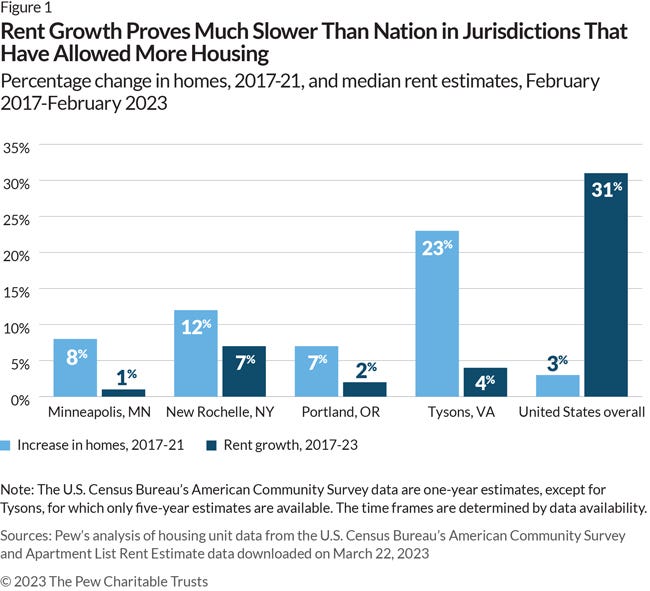

Fortunately, some cities (and states) are taking action and getting results. A recent report by Alex Horowitz and Ryan Canavan of the Pew Charitable Trusts finds that although rents have risen across the country, cities that have built more housing have seen much smaller increases:

Now, none of this is to suggest that new market-rate housing will solve the rent crisis in American cities. Been et al. (2018), who offer the most wide-ranging and authoritative defense of market-rate housing supply among all the papers I’ve mentioned, are absolutely right when they argue that deregulation is not the only thing we need to do:

Because the price effects of market-rate construction may be slow to materialize and are unlikely to be sufficient to address the needs of very low-income households, it is important for local governments to seek to ensure that new supply comes on line at a range of price points, so that growth is balanced among the various income levels in the community.

That’s why YIMBYs have also pushed hard for more social housing — a fact that Gopal and Clark, in their rush to describe YIMBYism as a “trickle-down” approach, conspicuously fail to mention.

But as Horowitz and Canavan show, allowing more market-rate housing can absolutely blunt and slow the rise in rents, even if it doesn’t reverse it entirely. So it’s something we should definitely do!

Look I know that the Left-NIMBY worldview is a seductive one. The movement of knowledge industries and high earners into city centers is scary and disruptive for lots of people, and it’s tempting to tell ourselves that we can make it go away if we just block new apartment towers from going up. But we can’t. We aren’t in total control of the vast economic forces that are causing changes in our cities, and kicking out blindly at the most visible symbols of those forces won’t make them go away. Those new housing towers didn’t cause the rain; they’re the umbrella. And knocking the umbrellas out of people’s hands won’t bring back the sunny skies.

Excellent, well researched article. Thank you.

Big fan of getting these types of posts every 9 months or so with updated research links ;)