It’s been quite a week for the Ukrainians fighting for their homes and their lives. The Ukrainians launched two offensives against the Russian occupiers, one in the south at Kherson, and one in the north near Kharkiv. The southern offensive has made only modest progress so far, but the northern offensive broke through weakened Russian lines, seizing the strategic railway hub of Kupiansk and the key staging area of Izyum. It all went down stunningly fast:

Now the Russians are in disarray, and the Ukrainians may be able to take back more of their territory in the ensuing chaos. The Ukrainian offensive — far swifter and more decisive than anything the Russians have managed since the beginning of the war — makes it seem less likely that Russia will be able to force major territorial concessions from Ukraine.

If you want to follow the unfolding situation more closely, check out my Twitter list for the Ukraine War, or my short list with only a few key experts.

This is obviously a great development — Ukraine are clearly the good guys in this war, a peaceful country invaded by a brutal, imperialistic neighbor without provocation, and it’s good to see them throw the invaders back. But it also illustrates some important principles about the broader conflict unfolding across our world between liberalism and illiberalism.

Those words are tricky to define, and it’s even trickier to map the messy, complex conflicts of our real world onto that simple dichotomy. The real world is neither Star Wars nor Lord of the Rings. But the events unfolding in Ukraine should provide some object lessons about what’s worth fighting for, the true sources of collective strength, and how the U.S. should proceed going forward.

Acting tough vs. being tough

“You mistake, too, the people of the North. They are a peaceable people but an earnest people, and they will fight, too.” — William T. Sherman

Americans, of course, tend to care first and foremost about our own culture wars. At the very outset of the Russian invasion, right-wing media personality Matt Walsh crowed about how Russian masculinity and toughness would carry the day:

This perception that Russia was a bastion of traditional masculinity was probably why many social conservatives seemed extremely willing, almost eager, to believe early Russian propaganda about an imminent victory:

Half a year later, Russia has stumbled from defeat to defeat. Its forces were evicted from the north of the country early on, a drive toward the port of Odessa was defeated, its navy suffered a series of catastrophes, and now the Ukrainians have shattered Russian lines in the northeast. Russia’s only real progress in the war has been using overwhelming masses of artillery to reduce the city of Mariupol to rubble and to take an embarrassingly small pocket of territory in the country’s east.

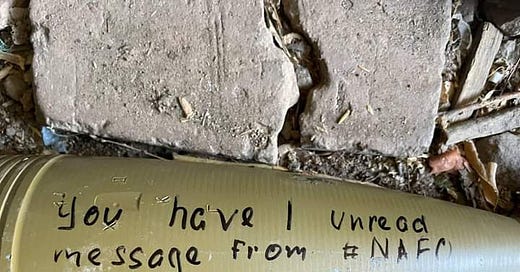

This is not purely due to the personal qualities of the soldiers involved; much of it depends on equipment and leadership. But the failure of Russia’s bully-boy fierceness to translate into real military gains should make us deeply question the narrative that the tough soldiers of authoritarian countries will overcome a supposedly feminized modern democratic society in any direct contest of strength. This meme is a joke, but there is a nugget of deep truth here:

Of course, there is no lack of he-men in the Ukrainian military. But their attitude is one of quiet, often self-effacing endurance, rather than ravening aggression. Nor do they see war as an opportunity to reinforce traditional gender divisions; by some estimates, more than 20% of Ukraine’s military personnel are women.

This difference can be seen in the two sides’ different approaches to human rights. The Russian military has become notorious for committing atrocities as a matter of routine, while Ukrainian telephone operators have to reassure surrendering Russians that they won’t be castrated. Russia massacres Ukrainian civilians, not just out of some inherent bloodthirst, but to seem fierce and terrifying; the Ukrainians respond by simply blowing up more Russian vehicles. And when push came to shove in the recent offensive, the Russians were more than willing to abandon their equipment and flee.

In other words, there is a clear difference between acting tough and actually being tough. The former is all about outward fierceness and savagery, while the latter is about the inner ability to endure hardship and pain and fear and still keep fighting effectively.

In fact, this difference is a reason why authoritarian, illiberal regimes traditionally underestimate more liberal ones. The Nazis and Imperial Japan both believed that the U.S. was weak due to capitalistic decadence and racial diversity. The Confederacy said similar things about the people of the North. The rhetoric of Putin and his cronies regarding the West’s supposed weakness echoes those earlier allegations. So does the rhetoric of Xi Jinping and his cronies in China, who have worked to expunge Western culture lest it lead to decadence. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine was obviously motivated in part by an extension of this “weak, decadent” stereotype to any nation aligned with the West

Just as Hitler and the Japanese militarists were wrong last century, so Putin and Xi are wrong this century. If the U.S. proves weak, it will only be from internal political division, not from any sort of decadence. And countries aligned with the West, like Ukraine and Taiwan, are not going to be pushovers simply because they don’t oppress gay people or mutilate prisoners.

What are “liberals” actually fighting for?

“And it’s root, root root for the home team/ If they don’t win it’s a shame” — traditional American song

“China is a big country and you are small countries, and that is a fact.” — Yang Jiechi, Chinese foreign minister, 2010

Part of the reason Ukraine demonstrates quiet resilience instead of chest-thumping savagery is that they haven’t been inculcated with imperial arrogance the way Russians have under Putin. Part of it is because Ukraine wants to emulate (and join) the West. But a big part of it is simply that Ukraine is on the defense. Motivating yourself to go onto someone else’s land and slaughter them requires a very different mindset than motivating yourself to defend your home and family.

This difference in goals, I think, helps us understand what we instinctively mean when we say “liberal” and “illiberal”. A big part of the distinction is about differences in political and social systems (as I’ll discuss in a bit). But a lot of it is simply about conquerors vs. defenders. There’s a clear difference between the vision of a world where “the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must”, and the vision of a world where every country is free to determine its own destiny.

To some extent, being “liberal” in terms of geopolitics simply means identifying with the defenders. It means upholding the idea that we now call “Westphalian sovereignty” (even though its connection to the actual Peace of Westphalia is tenuous). That’s an international regime of fixed borders and a respect for the interests of small nations. So far, the fixed-border norm has proven extremely useful in the decline of interstate conflict since World War 2 — a norm that Russia has flagrantly violated with its invasion of Ukraine, thus portending a darker, more violent world.

A liberal regime is also a regime that respects human rights. The U.S. tried very hard to enshrine the idea of universal human rights into the postwar system (though the success of that effort is open to debate). In fact, this is the far more common definition of “liberal” — a political system based on human rights and democracy. It’s this aspect of liberalism that leads to tolerance of racial minorities, sexual minorities, non-traditional gender roles, and all the other that authoritarians consider decadent. It’s also the reason “liberal” is sometimes identified with free markets, even though in practice most “liberal” countries are what we’d call social democracies.

The notions of liberalism-as-Westphalian-sovereignty and liberalism-as-human-rights-and-democracy obviously come into conflict quite often. When a country oppresses or slaughters its people, do you try to intervene or not? But there’s also a conceptual thread that unites the two notions of liberalism — the respect for autonomy even in the face of power differences. There’s a natural analogy between a respect for small nations and a respect for individuals. In both cases, the core idea is that might does not make right.

This is exactly what the neoconservatives got so disastrously wrong in the 2000s. Though they tried to conceal it with a fig leaf of democracy promotion and liberal interventionism, ultimately the neocons’ promotion of the Iraq War was rooted in the idea that, as Karl Rove so infamously is alleged to have said, “We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality.” This led to a gross violation of the principle of Westphalian sovereignty — the U.S. launched an unprovoked invasion of another country, in defiance of international outcry. And it predictably led to human rights violations as well, including widespread torture. Once you embrace the idea that might makes right, you tend to embrace it on an individual level as well as a collective one.

Thus it was the Iraq War, rather than Putin’s invasions of Georgia or Ukraine, that struck the first huge blow against the liberal order that the U.S. built after World War 2. By abandoning its liberal principles, the U.S. in its neocon period sent a clear message that the world was once again going to be a place where the weak suffered what they must.

That’s a failure we shouldn’t forget. Just because the U.S. has “the land of the free” in our national anthem doesn’t mean that anything we do is automatically and definitionally liberal. The morality of the Ukraine War is clear, but the world can’t so easily be divided up into Team Good Guys and Team Bad Guys. Even as we work to oppose the expansionist dreams of Putin and Xi, we should work equally hard to restore the U.S.’ moral commitment to liberalism both inside and outside its borders.

Ukraine has reminded us Americans of our country’s proper role in the world — as the spoiler of empires and the defender of human rights.

Strengthening the liberal world

So Ukraine’s successes have sent us messages about what’s worth fighting for. But they have also sent us a message about how to most effectively prosecute that fight. The recent offensives succeeded not just because of the courage, tenacity, intelligence and adaptability of Ukraine’s warriors, but because of massive military aid from the West. The most famous and probably the single most effective piece of equipment has been the HIMARS rocket artillery system with GMLRS precision-guided rockets:

Those rocket trucks were able to drain Russia’s artillery of ammunition via constant strikes on ammo dumps, as well as taking out command posts and air defenses and eventually backing up the Ukrainian counteroffensives.

In fact, this is far from the first time the U.S. has done this. In this thread, Paul Poast explains how U.S. aid for Ukraine today mirrors our aid for the Soviet Union when they faced Nazi invasion and extermination in World War 2:

Acting as the “arsenal of democracy” is a proven strategy of success. The U.S. should therefore stay the course on aid to Ukraine, despite complaints from both rightists and leftists that the money could be better spent elsewhere. No, it could not.

Of course the U.S. has self-interested reasons for supporting Ukraine. If one of America’s most powerful and dogged rival superpowers can be brought low with an investment of just $40 billion, that’s obviously a win from a realpolitik perspective. But only a total cynic would think that these are the only reasons. A successful defense of Ukraine will be a powerful blow against the dawn of a new age of imperial expansionism. In an interview in March, eyeing Russia’s invasion, a Chinese professor wrote:

The old order is swiftly disintegrating, and strongman politics is again ascendant among the world’s great power…Countries are brimming with ambition, like tigers eyeing their prey, keen to find every opportunity among the ruins of the old order.

Preventing that future should be the core goal of liberalism in this day and age.

But if that effort is successful — if the movement toward a dark world of conquest and totalitarianism can be averted — the world order that will emerge will not look like the “unipolar moment” that prevailed in the 1990s. The U.S. is no longer capable of serving as a benign hegemonic guardian of liberalism, if we ever were to begin with. In the face of rapid catch-up growth by developing countries, we are simply too small. And the Iraq War and the amoral Trump administration both show that our internal politics are fickle enough that the world cannot afford to rely on America always doing the right thing.

Instead, we must work toward both a multilateral defense against illiberalism in the present, and a multilateral liberal order in the future. Ultimately, the only guarantee of a world without bullies is for people and countries to rally to each other’s defense. Right now, the successes in Ukraine are showing the way.

The key belief of illiberalism is that the world is abuse or be abused and that's never going to change. The key belief of liberalism is that humans are capable of inventing ways (democracy, human rights, the rule of law) to create a space where it doesn't have to be like that.

There's another element of Liberalism & war that's frequently overlooked or underrated.

Bismarck famously said that 'People never lie so much as after a hunt, during a war or before an election', and while courage and strength of will are obviously key to winning, so to is being able to separate and prioritise fact from fiction (particularly unwelcome facts over comforting fictions), in order to make the right decisions.

Anti-liberal societies are exceptionally bad at this, and prosecuting a war with false info and inflexible world-view is about a sure -fire way of losing it as you can get.