“The easiest way to inject a propaganda idea into most people's minds is to let it go through the medium of an entertainment picture when they do not realize they're being propagandized.” — Elmer Davis, head of the Office of War Information

The image above is from a short film called Don’t Be a Sucker, first released in 1943 during the height of World War 2 and then re-released in 1947 after the war’s end. The film depicts a nativist, bigoted demagogue railing against minorities while standing in front of a flag and claiming to be an “American American”. In the film, a man watching the show — representing the American everyman — meets a Hungarian refugee who warns him about how anti-minority scaremongering was how the Nazis came to power in Germany. Meanwhile, the film’s narrator extols American diversity and the inherent strength of a liberal society. Don’t Be a Sucker remains highly influential to this day, and was widely circulated as a warning against fascism in the aftermath of the Charlottesville demonstrations in 2017.

If you haven’t seen it, it’s well worth your 22 minutes:

Who produced this film? Was it some anti-fascist citizens, concerned about stemming the tide of nativism at home and fighting back against the Axis powers abroad? Was it some nonprofit or citizens’ group? Nope. Don’t Be a Sucker, the film that progressive youth were sharing so widely in 2017, was made and promoted by the United States Department of War.

Nor was even close to being the only film that the Roosevelt and Truman administrations used to persuade Americans to get behind the fight against fascism. Another famous example is Why We Fight, a series of films directed by the then-famous director Frank Capra during World War 2 to explain the U.S.’ entry into the war to a skeptical public. You can watch the entire series on YouTube if you like. I watched Part 1 in high school, and I vividly remember a graphic depicting how the Axis powers wouldn’t be satisfied with Europe and Asia, and would eventually come for the United States in the end:

I remember being persuaded by this graphic; not because I thought the hypothetical invasion plan looked particularly plausible, but because it made me think hard about whether Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan would have left America alone after taking over most of the rest of the world. It seems highly unlikely that they would have.

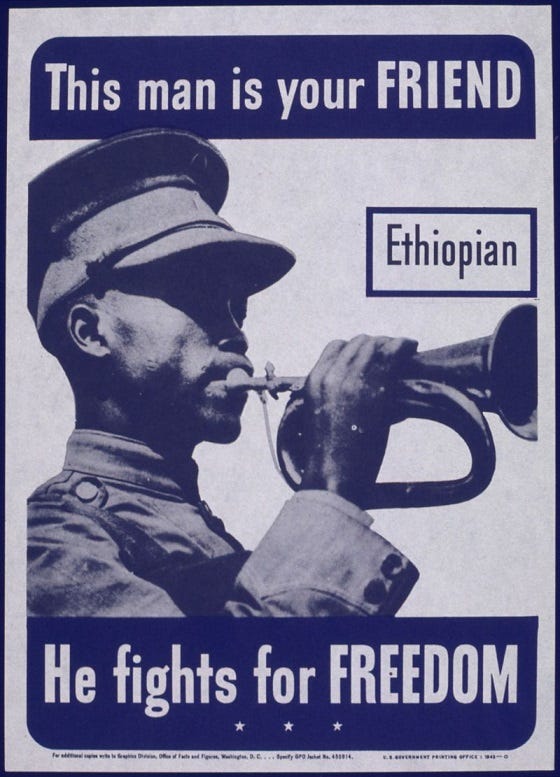

But films justifying America’s role in World War 2 were only the tip of the iceberg when it came to government communications in that era. The Roosevelt Administration created a whole Office of War Information, which tried to convince the country of both America’s fundamental unity and of the primacy of liberal values. There were also innumerable other such persuasive efforts, such as the famous posters that tried to convince fearful Americans to trust their nonwhite and communist allies.

In some cases, such as the government’s positive portrayal of Chinese-Americans, these efforts led to amelioration of long-standing racial animosities.

Nor did FDR’s efforts to convince the American public of his worldview begin when the bombs fell on Pearl Harbor; the New Deal included plenty of similar messages of liberalism, unity, optimism, and so on. And of course there were FDR’s own famous “fireside chats”, where he took to the radio to personally explain the thinking behind his policies.

These efforts weren’t all-powerful, but they almost certainly did move the needle somewhat. A postwar study of Don’t Be a Sucker found that the film decreased anti-outgroup prejudice by about half — not perfection, but far from useless either. It also made Americans more confident that their country would never fall for fascism; some see this as encouraging complacency, but I think it’s reasonable to conclude that a nation that would be persuaded by a film like Don’t Be a Sucker is a nation with deep-seated liberal values and institutions.

Fast forward eight decades, and government messaging efforts like FDR’s are basically nonexistent. At some point during those eight decades, Americans collectively concluded that this sort of message is propaganda — the kind of thing the Nazis and the Soviets did — and is therefore represents the kind of government thought control that a free society should desperately avoid. We decided it was best for the government to step back from the fray of public opinion, guarding the principles of free speech from an Olympian remove, and letting the best ideas prevail in a neutral Marketplace of Ideas. That approach seemed to do fairly well for us in the late Cold War.

But the governments of other powerful countries didn’t all take the same lesson from the 20th century. China and Russia in particular have both doubled down massively on the use of propaganda in the modern age. Vladimir Putin’s regime turned Russian broadcast media into a web of disinformation so dense that for someone not steeped in that alternate universe, the experience of watching Russian TV for five days can be psychologically crushing. China, meanwhile, took to the internet with a vast army of censors and rules, shutting out foreign information sources, tightly policing topics of conversation, and sending out paid armies of influencers to promote the government line anonymously.

That’s all perfectly tragic for the peoples of those distant lands, to be sure. But now consider what happens when those countries turn those formidable, well-honed propaganda apparatuses on the American public. There was no internet in the 1940s, but in the 2020s, every American has a direct connection to the governments of fascist powers sitting in their pockets. How do you know if the person railing against Ukraine in your Twitter mentions is a Russian operative? If you see a lot of anti-Taiwan videos on TikTok, how sure are you that the Chinese government didn’t instruct the app’s owners to tilt the algorithm in favor of that content?

The fact is, you don’t know. Nor does anyone in the world — those governments included — actually know how much their overseas propaganda efforts move the needle on U.S. public opinion. But we definitely know that Russia and China are trying. Russia’s “troll farms” are well-documented, and Europe has been flooded with TikTok ads echoing the CCP’s party line on various topics. These efforts go by various names — “influence operations”, “cognitive warfare”, etc. — but there seems to be a broad agreement among experts that they’re real and that the governments of Russia and China believe they’re important. The worry crosses party lines — even many Republicans who scoff at the idea that Russian trolls might have promoted Trump in 2016 are worried about Chinese influence reaching us via TikTok. Representative Mike Gallagher writes:

Via TikTok, Chinese state media pushed divisive information about U.S. politicians ahead of midterm elections. Numerous reports have found TikTok censoring and suppressing content about Xinjiang, Tibet, Tiananmen Square, and other issues sensitive to the CCP. TikTok has also suppressed content about LGBT issues, and even temporarily blocked a teenage American Muslim activist who criticized the CCP’s treatment of Uyghur Muslims…

Allowing a CCP-controlled entity to become the dominant player in America would be as if, in 1962, right before the Cuban Missile Crisis, we had allowed Pravda and the KGB to purchase The New York Times, The Washington Post, ABC, and NBC.

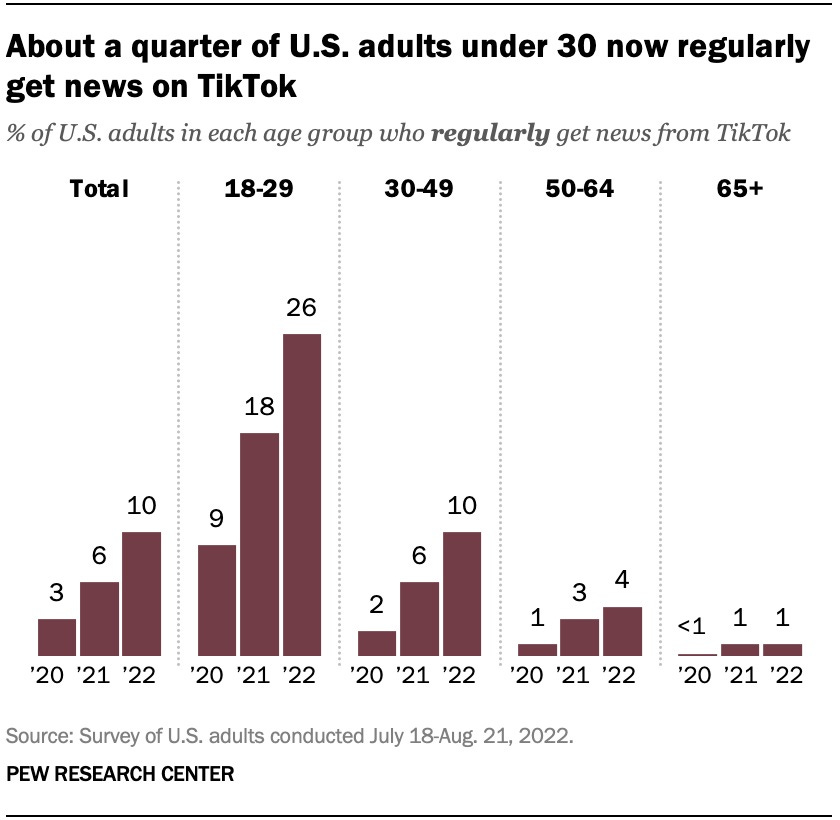

He’s right to be worried. TikTok is especially influential among the young generation of Americans, who increasingly get their news from the video app:

Personally, as someone whose job includes absorbing large amounts of Twitter, I can say that pro-Russian narratives have been especially common on that platform. But CCP control of TikTok messaging in the event of an invasion of Taiwan scares me the most.

Fortunately, the Israel-Gaza War seems to have prompted the Biden administration to worry as well. (I’m sad that it took a morally ambiguous case like the Israel-Gaza War to demonstrate the potential power that TikTok gives China over our youth, but I guess at least people are waking up now.)

Who has the power to stand up and push back against a flood of online Chinese and Russian government propaganda? Currently, under the U.S.’ marketplace-of-ideas doctrine, that duty falls to private citizens. It’s normal, everyday Americans who must spend hours upon hours of their day replying to viral tweets and desperately making TikTok rebuttal videos, lest their fellow Americans fall victim to the siren song of totalitarianism. We are all somehow expected to sacrifice hours of day to do thankless, unpaid work pushing back against illiberal narratives spread relentlessly by people for whom spreading those narratives is a full-time salaried job.

Meanwhile, under this onslaught of Russian and Chinese messaging, the U.S. government stands serenely aloof from the fray. Administration officials will give speeches and pen the occasional op-ed in Foreign Affairs, government officials make anodyne tweets, and the Voice of America is still putting out articles that no one reads, but the kind of coordinated forceful official advocacy of liberal values that we saw under FDR is considered propaganda to be avoided at all cost.

It should be obvious that this is a recipe for liberalism’s utter defeat. Imagine if a country being invaded by a conquering army declared that government shouldn’t get involved in violence, and outsourced the defense of the nation to private citizens with homemade guns? That is effectively what the U.S. government is doing by ceding the information sphere to foreign governments and private citizens. We are so afraid of being propagandists that we are refusing to counter the efforts of powers who have no such fear.

The U.S. government needs to get back into the information warfare game.

First, this means articulating liberal values to the American people, and explaining how U.S. government actions are intended to promote those values. The right messaging medium probably won’t be preachy films and stylized posters like it was in the 1940s (though who knows, maybe it might!). Instead it might involve 15-second videos, or podcasts by elected politicians, or whatever messaging best reaches the online populace of the 2020s. Despite being a modestly popular blogger, I’m not really the expert in what moves the masses. But someone out there is, and the government can find and employ them like it employed Frank Capra in the 1940s.

Second, the government needs to act to limit the ability of the totalitarian powers to push their own messaging to our people. FDR’s Office of War Information reviewed Hollywood films to make sure they weren’t anti-American; that sort of blunt censorship was almost certainly unconstitutional, and shouldn’t be considered today. But there are analogues that do make sense. The most important step is probably to force TikTok to sell itself to an American company — a move the U.S. government has repeatedly considered and then shied away from.

There are, of course, dangers to this approach. The U.S. government’s censorship efforts during the Vietnam War silenced much-needed dissent in that conflict, and the Bush Administration was famously less than forthright with the American people when persuading them to accept a war in Iraq. And there’s always the danger that the administration in power will use government resources to present events in a way that puts itself in a positive light and sours people on the opposition.

These are potential abuses that we need to take seriously. Instead of censorship, our defensive efforts should focus entirely on preventing foreign governments from controlling our information ecosystem. And all U.S. government communication should be open and honest about where it comes from, so that it can be subject to the same scrutiny that any other piece of information receives.

But simply sitting back and trusting in the Marketplace of Ideas to reach an optimal equilibrium is no longer a viable option for a liberal society. Totalitarian powers are on the march, and social media gives them the opportunity to reach American hearts and minds more directly than ever before. One of our government’s essential functions is to guard us against such powers. If we force it to abnegate that function, mainlining totalitarian propaganda out of fear of creating our own, we’re all a bunch of suckers.

'a morally ambiguous case like the Israel-Gaza War'

There is no moral equivalence between Hamas and the state of Israel in this war. Their fundamental aims are completely different. Hamas' stated goal -- stated again and again -- is to wipe Israel and the Jews out of existence. Isarael's goal is to live peacefully. Hamas brags about brutalizing and killing babies, children and women. Israel goes to tremendous effort to avoid killing civilians even as Hamas pushes their own civilian people into the front lines by hiding behind them or preventing them from leaving. One is pure evil; the other is not.

The United States has liberal norms and liberal institutions. But we don’t have a firm liberal consensus and the polls currently suggest that an illiberal candidate might win the next presidential election.

What’s the version of this proposal that is still a good idea if Donald Trump is president and the whole apparatus of government funded media is run by Steve Bannon?