The special pandemic unemployment benefits — also known as Pandemic UI — were one of the most wildly successful government programs the U.S. has ever undertaken. One person told me that it was the only time he had ever felt like the government really cared about him. It was a bipartisan program, with former Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin playing a key role in its inception (even though Mitch McConnell’s obstructionism allowed it to temporarily lapse in the fall of 2020).

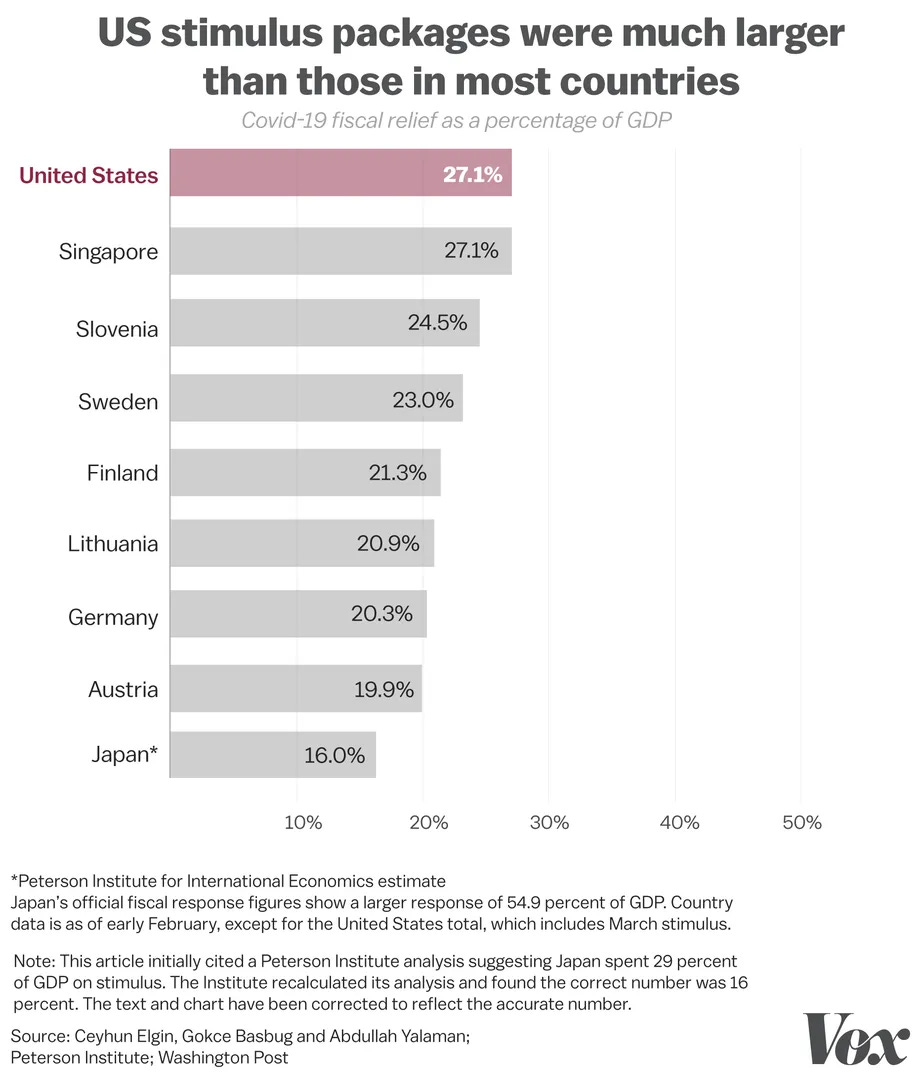

Pandemic UI was a key reason — perhaps the key reason — why the U.S.’ economic response to COVID was so much more generous than most countries’. Vox’s Dylan Matthews has a great rundown making the relevant comparisons. Here is the relevant chart:

As Matthews notes, U.S. relief was so generous that Americans’ disposable income actually rose during the pandemic, rather than falling as in many European countries. Pandemic UI was a huge part of that.

Now, you might think that paying people to sit around at home and not work would reduce the number of people working. But in fact, a large amount of empirical evidence shows that it didn’t — at least, not during the pandemic’s early phase:

First, there’s this paper by Altonji et al. from late July, which uses private employment data along with individual differences in the percent of a worker’s wages that Pandemic UI replaced (called the “replacement rate”), in order to measure the effect of Pandemic UI on employment. Their results are unambiguous…Other papers by Bartik et al. and Dube et al., using different data sources, find exactly the same result. And Ernie Tedeschi has a research note finding the same.

The theory of this is well-understood — given a choice between holding onto a job and going on a temporary dole, rational people would generally choose to keep the job.

But results like this aren’t laws of the Universe; they’re contingent on what’s actually happening in the economy. And what’s actually happening now is that the pandemic is on the way out:

This is primarily due to the U.S.’ rapid vaccination effort. That effort is now flagging, thanks in large part to a campaign of vaccine refusal among certain parts of the political Right. Thanks to that politicized tantrum, COVID will probably persist at a moderate level in many pockets of the U.S. But in most of the country, life will return to normal — mask mandates will end, indoor dining will return, people will feel safe going to shops and concerts and sports games (perhaps with vaccine passports). Fear of the virus was always the big constraint on the economy, and that fear is ebbing fast.

That means that companies should be hiring robustly in anticipation of booming consumer demand. And for a few months this looked to be true. But in April, hiring slackened dramatically, with only 266,000 workers added to payrolls compared with a predicted 1 million. The unemployment rate actually rose.

Normally, I tell people to ignore the monthly payroll numbers. These numbers are quite noisy, and one month is usually much too little to establish any kind of a trend. But a miss of 734,000 is way too big to be random error; something is not working the way it’s supposed to in this recovery.

Now, it’s not all bad news. As my former undergrad econ student and current Bloomberg econ reporter Matt Boesler points out, the reason labor unemployment rose is that labor force participation actually ticked up. That means more people are out there looking for jobs. Underemployment actually fell, which is a sign that people are looking to transition to full-time work. And the leisure and hospitality industry, one of the hardest-hit by the pandemic, continues to be a bright spot.

So what are we supposed to make of this? Here are several hypotheses for what might be going on:

Businesses are uncertain, both about policy and about whether the pandemic is really over (thanks to antivaxers), and this uncertainty is making them hesitant to hire.

Many schools remain closed, forcing parents to do intensive child-care duties at home.

Businesses aren’t used to raising wages to attract workers, and are simply holding out for a while to see if they can get away with not raising the wage. (Update: Though it's important to note that some are raising wages considerably.)

Pandemic UI is now giving people a significant incentive to delay going back to work.

These aren’t mutually exclusive. Data is patchy and is still coming in, so it will be months before we can get an idea of how much each of these forces matters (or if it’s also some other thing that’s not even on this list).

We do have a few scraps of info. For example, we know that existing workers are being worked harder:

This implies that businesses do see higher demand, and are trying to meet that demand without hiring more workers.

We also know that the ratio of job openings to unemployed workers is high, suggesting that employers are trying to find new workers:

And we know that workers are quitting their jobs more, which suggests that people are optimistic about their prospects of finding better jobs:

All of these things seem to mitigate against explanation (1); demand seems robust, and fear and uncertainty on the part of either workers or businesses does not seem like the limiting factor for hiring. Instead, it seems like either businesses are just temporarily trying to get away with not raising wages, or there are some subgroups of workers who aren’t ready to get jobs yet, whether because they’re busy with child care or they’re happy to keep taking Pandemic UI for a little while longer.

Note that the theory of why Pandemic UI didn’t kill jobs when the economy was collapsing is perfectly consistent with the idea that it’s holding back employment now. When the main determinant of employment is how many people leave their jobs, it makes sense that people would hang onto them rather than go on a temporary dole. But when the main determinant of employment is how many people leave their homes and go get jobs, it makes perfect sense that those who are already on the dole might choose to stay there for a few more months.

Anyway, we won’t know for a while how much each of the factors listed above really matters, so we have to try to address all of them. The child care problem can only be addressed by reopening schools (and vaccinating the kids). There are probably ways to solve “wage hike hesitancy” as well. But just in case Pandemic UI is one of the big reasons holding back full recovery, we should modify the program.

It’s important to realize why we did Pandemic UI in the first place. It was a form of disaster relief — a kind of retroactive social insurance, to make sure people came through the pandemic in good financial shape instead of destitute and ruined. As soon as the disease itself is no longer a danger, that mission has been accomplished.

Thus, in order to help the labor market along, we can replace the Pandemic UI program with something that accomplishes the same purpose while also encouraging people to get jobs. The most common idea for doing this is to offer workers a signing bonus — anyone who goes off of Pandemic UI and gets a job gets a $4000 check (equivalent to a little over 3 months of Pandemic UI at current rates). That would mean that if you go get a job, you get to earn a wage AND get the cash, whereas if you stay at home, you only get the cash. Essentially, this approach gives you the option of taking all or most of the Pandemic UI money you would have received by staying at home for a few more months, but as an up front payment, and then going back to work and starting to earn more money immediately.

Advantage: job.

Adding signing bonuses to Pandemic UI is a MUCH better approach than simply winding down the program and hoping that fear of destitution will force people back onto the payrolls (as some Republicans will probably suggest). Doing this probably won’t cost the government any more money than simply keeping Pandemic UI going as normal; in fact, it will probably save us money, by getting people off of the unemployment rolls and goosing demand throughout the economy.

In fact, the government could also pay signing bonuses to companies that hire workers at significantly higher wages than what they were paying before — a temporary wage subsidy. Not only would that provide additional impetus to hire, it would help normalize the habit of offering higher wages to attract workers.

So these policies could help kick the labor market out of its current doldrums and produce the rapid recovery we’re all expecting from the end of COVID. They won’t represent a rejection of Pandemic UI — instead, they’ll simply represent an acknowledgement that as conditions change, policy has to change too. Pandemic UI was never meant to be permanent, and it’s time to replace it with something better.

I suspect if the UI bonus was made permanent, it would become a default minimum wage hike.

My brother-in-law, who owns a fast food joint, is having problems getting workers. But I also know, it’s partly because he doesn’t wanna pay what he needs to pay.

The whole thing sort of makes me torn.

One thing I thought about, which I don’t see mentioned a lot is that the hiring wage needs to be a decent amount higher than the UI rate.

For instance, in Idaho the UI is 448 + 300. Or 748 total. Which works out to $19 an hour. Which is way more than the typical restaurant salary.

If I was making $19 an hour staying home, I’m not gonna take a job unless I’m making $22 or $23 an hour.

Previously someone who earned $10 an hour would of receive reduced benefits, but right now I believe everyone gets max.

Quite frankly, if it wasn’t a family business, my wife would of stayed on UI benefits. She’s actually losing money by going to work.

Nice column Noah! Do you think that the feds and the state DOL could actually implement a UI bonus before its usefulness has passed? Many state UI agencies did not distinguish themselves during the pandemic. I recognize that it is normative in economics to ignore such implementation issues, but ...