Learn smart lessons from the L.A. fires, not stupid lessons

Ignore the political propaganda. We live in a world with more fires now, and we need to prepare for it.

Public social media — X, Reddit, Bluesky, and so on — has changed how we think about disasters. On one hand, because it floods us with information, it gives us the ability to draw reasonable, well-informed conclusions about terrible events much more quickly and arguably more easily than we could in earlier times.

On the other hand, the inevitable flood of misinformation and opportunistic politicking that inevitably accompanies any disaster raises our chances of being rapidly misinformed, and makes any calamity more socially divisive than it would have been before.

Compare the reactions to the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake — the first major natural disaster I can remember hearing about — with the reaction to the horrific wildfires burning through Los Angeles today. Back in 1989, the news responded to the earthquake for the first few days by simply showing photos and videos of the damage, telling stories about the victims, and generally just saying “Oh what a terrible disaster.” We didn’t have to be inundated with political opportunists rushing to blame the collapse of the Bay Bridge on affirmative action, or Reagan’s defense buildup, or whatever. On the other hand, I suppose most Americans didn’t end up spending a lot of time or effort thinking about earthquake preparedness.

In contrast, the social media reaction to the 2025 L.A. wildfires — which have already claimed five lives, left thousands homeless, and cost tens of billions of dollars — has featured all the finger-pointing and false rumors that we’ve come to expect from every big negative news event in America. Some rightists were quick to blame Ukraine aid for defunding the L.A. fire department; leftists blamed aid to Israel. Rightists also blamed DEI for supposedly making the L.A. fire department incompetent (without evidence, of course). I think the single wackiest take I saw was that Israel is responsible for the wildfires because the carbon emissions it released during the war in Gaza had exacerbated climate change:

Meanwhile, a lot of misinformation went flying around, especially regarding Los Angeles’ preparedness. A bunch of people claimed that fire hydrants ran out of water to fight the fires because it L.A. county had refused to fill its reservoirs. This turned out to be false; the water reservoirs and tanks were full (and this is true throughout California), they just ran out quickly due to enormous demand. An even more popular rumor, embraced by figures on both the left and the right, was that the city of L.A. had cut its fire department budget recently. That rumor was also false, as Politico reported:

[The] assertion [that L.A. defunded its fire department] is wrong. The city was in the process of negotiating a new contract with the fire department at the time the budget was being crafted, so additional funding for the department was set aside in a separate fund until that deal was finalized in November. In fact, the city’s fire budget increased more than $50 million year-over-year compared to the last budget cycle, according to Blumenfield’s office, although overall concerns about the department’s staffing level have persisted for a number of years.

Others mistook a one-time capital expense in 2024 for a 2025 budget cut.

In general, the misinformation, finger-pointing, and political opportunism flew fast and furious. But if you remained calm, resisted the urge to dunk on your political enemies, and watched the situation unfold, I think there were a few important signals you could extract from the storm of information. Basically, the lessons I take away from the horrific L.A. fires are:

The insurance industry as we know it is in big trouble.

Climate change is making wildfires worse, but there’s not much we can do about that right now.

Forest management needs to get a lot more proactive, but is being blocked by regulation.

Wildfire preparedness is just a lot more important than it used to be.

Insurance companies are not an infinite pot of money that can make everyone whole

If you crack open an introductory economics textbook, here’s how it says insurance is supposed to work. Suppose you have 100 people, each with 1% probability every year of losing their home in a fire. A home costs $100k. So each person pays an insurance company a premium of $1k a year. The insurer takes in $100k in premiums, and on average it pays out one claim of $100k per year. The company makes zero profit, and homeowners have zero risk of losing money from a fire.

In reality, it doesn’t quite work like that. People’s risks are correlated — if one person in California loses their home in a fire, it’s probably because it was an especially bad fire season, which means a whole lot of other people in California are more likely to lose their homes in a fire that same year. This is fine in principle — insurance companies can incorporate those correlations into their models, and adjust the premiums accordingly. But if too many people’s houses burn down in a single year, and they all use the same insurance company, then that insurance company won’t have enough money to pay out all the claims. The company will go bankrupt, and the homeowners won’t get their claims. This is called counterparty risk.

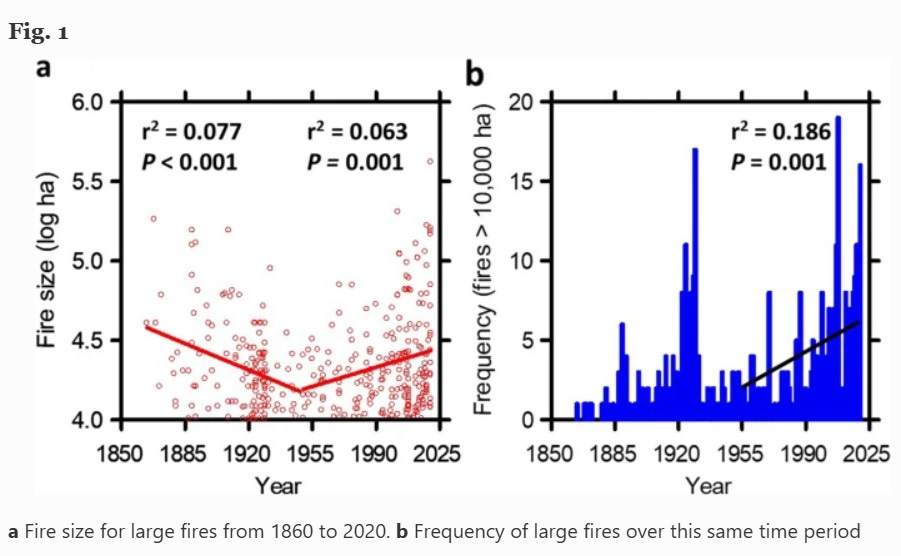

This weakness in the insurance system is getting more important over time, since big wildfires are becoming more common, especially in California:

Insurers can deal with this in two ways. First, they can raise premiums, based on models that take the worsening fire environment into account. Second, they can use reinsurance — they can buy their own insurance from truly giant insurance companies, so they don’t go bankrupt in a bad year.

Except in California they can’t actually do either of these things! In 1988, California voters passed a ballot proposition called Proposition 103, which says that if insurers want to raise their premiums, they have to get the raise approved by the government first. This means that if premiums go up, California voters will blame the insurance commissioner, who is democratically elected. So naturally, the commissioner tries to keep voters happy by forbidding insurance companies from charging higher premiums. In recent years, insurance companies have been begging California Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara to let them charge higher premiums in order to account for the increased risk of large fires, and for the reinsurance premiums they now have to pay. But Lara forbid them from doing so.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Noahpinion to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.