Jevons' Paradox won't slow the energy transition

Cheap cars didn't make us ride more horses.

Green energy is cheap and getting cheaper fast:

I’ve seen some people worry that Jevons’ Paradox will slow or even prevent the transition from fossil fuels to green energy. But don’t worry! This won’t happen!

Jevons’ Paradox is about efficiency. When you get more efficient at providing something, sometimes you actually end up using more of it instead of less. This is why policies that increase energy efficiency can occasionally lead to higher energy usage.

But green energy tech isn’t about efficiency; it’s about substitution. Jevons’ Paradox doesn’t apply.

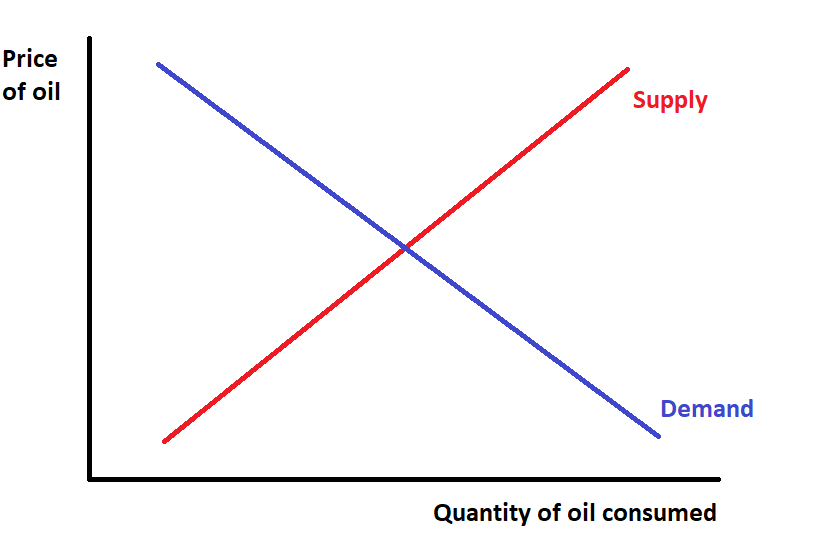

To see why, let’s explain why Jevons’ Paradox works. Suppose we’re talking about the market for oil. Let’s represent this with a simple supply-and-demand graph:

OK, so now suppose we become more efficient at using oil. Wikipedia depicts this situation in the following way:

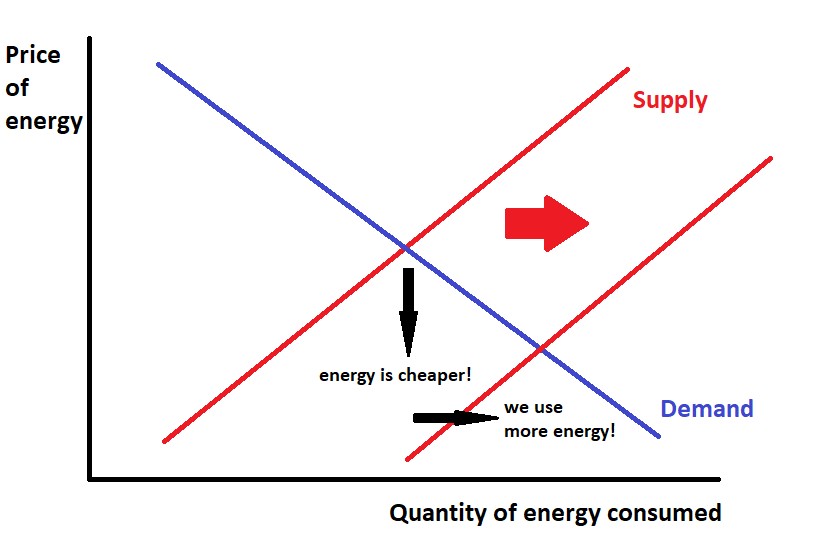

But cost doesn’t just move on its own. What’s really happening here is that the supply curve — which isn’t shown in the Wikipedia graph — has shifted to the right. If we become more efficient at turning oil into energy, it means that sellers of energy are able to provide more energy at any given price. So what’s really happening is this:

If the increase in energy use is large enough (which happens if the blue demand curve is flat enough, i.e. if demand is elastic enough), then it actually causes an increase in oil usage, despite the fact that we got more efficient at turning oil into energy!

That’s Jevons’ Paradox.

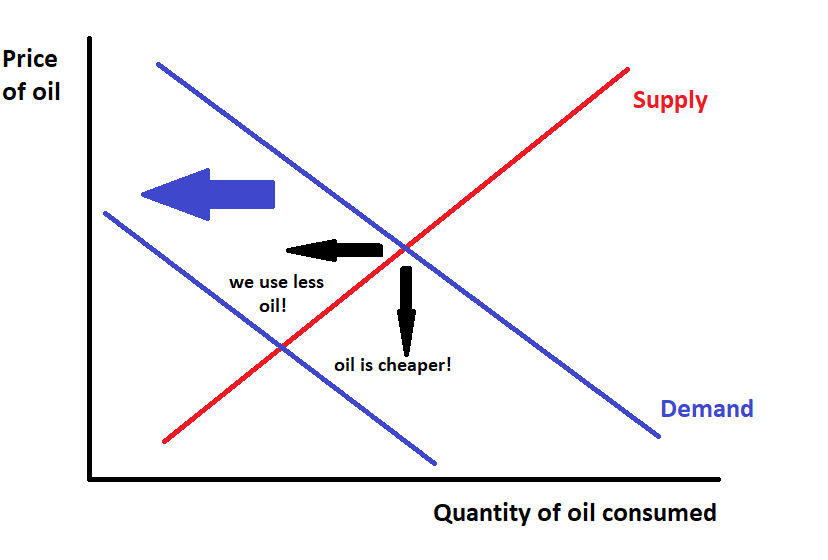

OK, but now let’s think about what happens when car batteries get cheaper. This is completely different from the example above. Car batteries are a substitute for oil. When substitutes for a good get cheaper, that good falls in price. Just think about pens and pencils. If pens get cheaper, people become less willing to pay high prices for pencils, since they can go buy cheap pens now instead. So demand for pencils falls.

Car batteries and oil are just like that. When car batteries get cheap, demand for oil falls. The situation looks like this:

Cheaper batteries mean that oil gets cheaper, and that we also use less oil.

At this point, you might ask: “OK Noah, but energy gets cheaper as a result of cheap batteries. Doesn’t that mean that people will use more energy, just like in the first example earlier? And doesn’t that mean that the people who still get their energy from oil will use more oil?”

Nope!

The reason is that in the second example, the cost of getting energy from batteries goes down, but the cost of getting energy from oil stays exactly the same. A barrel of oil still costs the same to pump out of the ground and refine and deliver to the gas station. An internal combustion car still gets the same amount of energy out of a gallon of gasoline.

So what happens when batteries get cheaper is that the quantity of oil consumed just goes down. Marginal, expensive-to-extract oil like the Canadian tar sands will no longer be worth it to extract; for the same cost, you would be better off just building some batteries instead. So people will just leave the expensive oil in the ground.

Remember: Jevons’ Paradox is about efficiency, not about substitution. Green energy is about substitution. It’s like when cars came along and replaced horses. So while Jevons’ Paradox can be a problem for energy efficiency policies, it’s not a problem for green energy. Don’t worry!

____________________________________________________________________________

(By the way, remember that if you like this blog, you can subscribe here! There’s a free email list and a paid subscription too!)

Does anyone consider more usage of energy a bad thing if the energy comes from renewable resources?

Hi Noah,

This is not quite precise, though the main point you make is exactly right. In your summary say "the cost of getting energy from oil stays exactly the same" and follow it up in the very next paragraph with "...so people will just leave the expensive oil in the ground" - which is contrary to your first point - the cost of oil is not staying the same, the expensive oil stays in the ground and the cheap oil continues to be extracted, so the average cost of each barrel of oil produced falls, along with the marginal cost of production.

The cost of producing the original amount of oil would remain the same, which is why the paradox isn't broken, but the cost per barrel of the oil that actually gets produced is lower.

As you pointed out, the price of oil will fall, and the price of energy as a whole will fall. If you assume people consume one or the other (oil or renewables) then as some people substitute away from oil to cheap renewables others will see a benefit to increasing their consumption of cheaper oil. The equilibrium can involve more oil consumption by the remaining oil consumers, but less total oil production/consumption (otherwise the price of oil would not be lower than when it started); the drop in oil prices is due to some portion of consumers shifting over to clean energy.

For example, assume 100 people initially consume 100 units of energy each, all in oil. Renewables become available at a lower price. 50 consumer switch to cheaper green energy and now consume 110 units of cheap green energy. The remaining 50 oil consumers stay on cheaper oil, and for a similar total cost now consume 110 units of cheaper oil energy.

Total oil energy consumed goes from 10,000 to 5,500, but it's up on a per-oil-consumer basis.

This doesn't mean your analysis that the paradox is broken is wrong - you're right that it won't hold.

I'm sure I'm not telling you anything you don't already know, it's just the ending explanation played a bit fast & loose with the terminology for me.