Greetings from Japan! I’m here for a two-week trip, so I think I’ll write a few posts about the country. Let’s start with the economy.

The first thing most people notice about Japan is how amazing the cities are. Tokyo in particular is a modern marvel. Gorgeously manicured plants surround immaculate, well-designed buildings. The restaurants and shops and entertainment options are intoxicatingly, fabulously infinite. The space is crowded yet always somehow serene, and you’re always within a few minutes’ walk of a train station that will take you anywhere you need to go. Japan has achieved feats of urban design and planning that no other country approaches, supported by a culture both unusually peaceful and startlingly creative.

But underneath the gloss of that fantasy-land exterior, Japan as a whole is not exactly thriving. For decades, the country’s real wages have drifted downward:

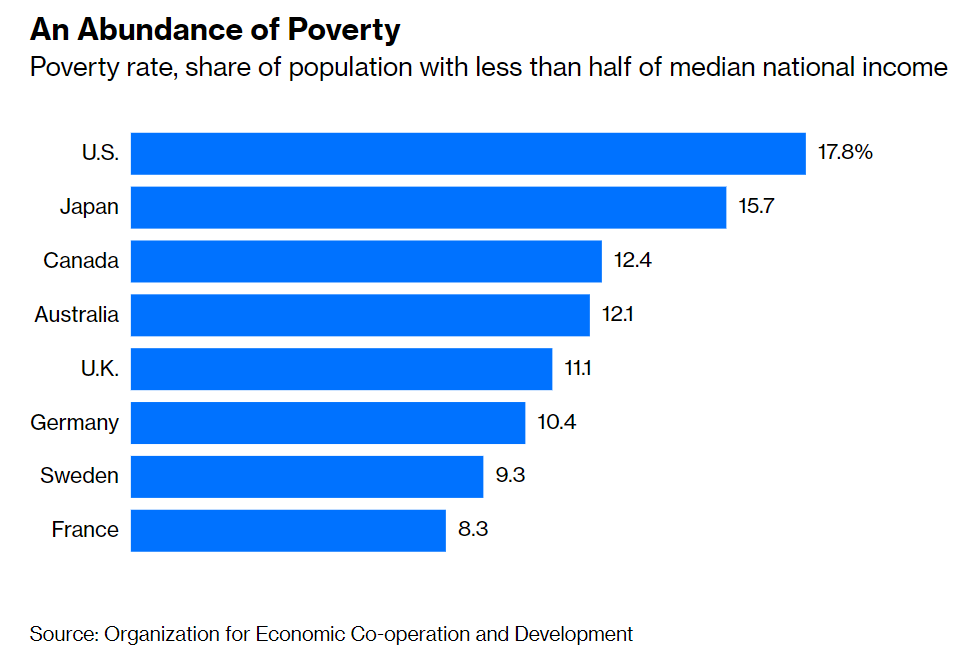

What does this mean in practice? First of all, it means that many Japanese people are suffering in quiet, hidden poverty. Tourists from the U.S. tend to assume Japanese people are almost all middle-class, both because we’ve been inundated with stereotypes of Japan as a highly equal society, and because you don’t see a lot of crime, dirt, urban decay, or the other visible markers Americans associate with poverty. But the stereotypes are wrong. Japan’s income inequality is about average for a rich country, and its relative poverty rate — defined as the percent of the population with income below 50% of the median — is higher than in Europe.

And that’s just relative poverty — remember, Japan’s average living standards are lower than others’ to begin with. Its per capita GDP at purchasing power parity is only 64% of the United States, 87% of France, and 92% of South Korea. Japan has not yet fallen back into the ranks of middle-income countries, but it’s in the lower part of the developed-country range.

As I wrote in a post for Bloomberg back in 2019, the extent of poverty in Japan is particularly galling to those who believe life outcomes are a result of our personal choices. Rates of drug abuse, teen pregnancy, out-of-wedlock birth, and crime in Japan are extremely low; Japanese poor people play by the rules and get screwed by the system anyway.

As Marika Katanuma notes, this poverty falls heavily on women. Women tend to be shunted into dead-end, low-paid part-time work, and many slip through the cracks in the pension system. It also falls disproportionately on the young, because of Japanese companies’ habit of basing wages mostly or entirely on seniority. These folks are out there scrimping and saving and working long hours at dreary, monotonous, soul-crushing jobs, sleeping in tiny bare rooms, desperately pinching pennies, able to afford fewer and fewer luxuries every year.

Even for those who manage to land a middle-class job, the lifestyle is often soul-crushing. Japan’s famous culture of overwork rewards employees who put in long hours at the office instead of those who accomplish tasks quickly and efficiently. This is mostly a result of the country’s notoriously low white-collar productivity rates —workers are working overtime to make up for broken corporate cultures. But it’s also likely that there’s a feedback loop involved; excessively long hours have been shown to make workers tired and ineffective.

This also means that for the country to keep growing, more and more people need to go to work. Women may not earn much in Japan, but about 74% of those aged 15-64 are working now — a considerably higher rate than the 66% in the U.S. The elderly are working more too:

In other words, practically everyone in the country is just grinding away forever and not getting nearly enough material reward in exchange.

Now, I don’t want to catastrophize here. This is still a rich country. Safety and good urbanism count for a lot. And there are certainly ways in which Japan’s quality of life has improved over the years — for example, suicide rates have dropped to all-time lows. Many Japanese people are quite happy with their lives. And though breathless newspapers will blame Japan’s economic situation for low birthrates or sexless youth or other negative social trends, these comparisons are generally overblown (Japan’s birthrates are higher than other East Asian countries, and sexless youth are a global phenomenon).

But it’s impossible to ignore the fact that this feels like a somewhat less happy, carefree country than the one I lived in back in the early 2000s. Years of declining living standards and rising work hours have taken a quiet toll. Something needs to be done.

Japan’s leaders are aware of the problem, of course, and they’re not completely sitting on their hands. The country increased minimum wages last year. The Financial Services Agency (in my experience one of the smartest and most proactive branches of Japan’s bureaucracy) is now going to require companies to publicly report their gender wage gaps. Prime Minister Kishida Fumio is introducing measures to shield consumers against rising energy costs, and has talked about policies to push Japanese companies to raise wages.

This is an OK start, but there are two things lacking here. One is a better welfare state. Japan has a middling level of social welfare spending — 21.9% of GDP, higher than the Anglosphere but lower than the rich countries of Europe. But much of that is simply government services — middle-class people paying taxes for health care and other services that they themselves consume. It’s when it comes to poverty alleviation that Japan really falls short, with a fiscal system less redistributive than most other rich countries. This OECD data is from 2005, but not that much has changed since then:

To make a long story short, Japan still relies mostly on corporations to bring about social equality, but those corporations haven’t been able to carry out that task for decades now. Government needs to step in to reduce the country’s disturbingly high poverty rate with fiscal transfers, such as a negative income tax or EITC type program.

The other, even more important factor is economic growth. When your country has a GDP of only $48,000 per person, redistribution will only take you so far; even with a better welfare state, low-income Japanese people will still be behind their German or British or French counterparts, because Japan is simply a poorer country. The country has to catch back up in living standards in order to give its least fortunate a shot, and to shake off the malaise that lies over its middle class. And this has to be done in a way that doesn’t require even longer working hours — in other words, productivity must go up.

In the next post in my series, I talk about some ideas for how to do that.

More immigrants, please!

In particular I believe Japan should consider entrepreneur visas. Everybody says (and has been saying for years) that Japan needs to let in more foreign talent. Why not focus on folks starting up businesses? If dysfunctional corporate culture is holding back the country's productivity (and thus ultimately growth, and living standards) one way to change that culture might be to import a bunch of business people from different, erm, cultures.

I see Noah is still using GDP/capita as a stand in for comparing standard of living between countries. I remain skeptical. Maybe we can have a column about the various ways of comparing standards of living some day. Pretty please?