First, the inflation news. The basic story is the same as in the last couple of months — headline inflation was very low, while core inflation was moderate but still above target. In fact, in month-to-month terms, overall prices fell last month, while core inflation accelerated slightly from 2.4% to 3.6%:

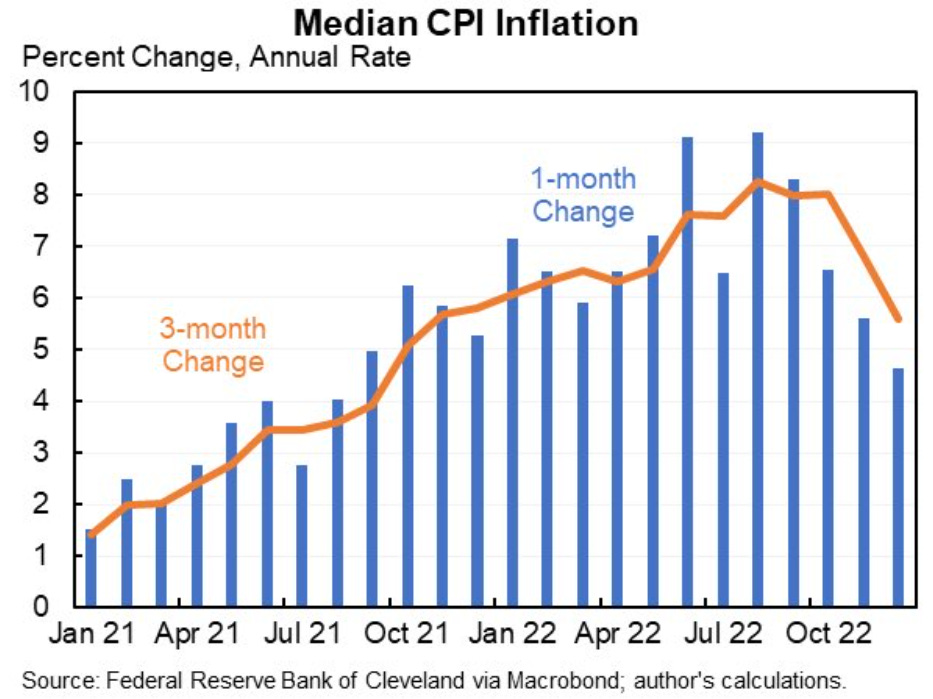

As always, check out Jason Furman’s thread for a good detailed breakdown. Also check out his thread on alternate inflation measures. My favorite of these is median inflation, which measures what the price of the typical product in the economy is doing. Here we see the same story, which is that inflation is slowing but still above target:

Anyway, there’s always quite a bit of noise in these numbers, especially the month-to-month ones. Some people like to cherry-pick particular products in order to justify their hawkish or dovish stances (apparently eggs got way more expensive last month), but unless the product is “oil”, or maaaaaaybe “semiconductors”, doing this just introduces more noise. The basic story here is pretty clear — inflation is decelerating, and has gone from an emergency to a disquieting nuisance. This pretty much fits with the news headlines, where you don’t see nearly as much worry about inflation anymore.

Now, many in the commentariat are worried not about inflation, but about a recession. The worry is that inflation is subsiding on its own, and that the Fed’s rate hikes are an unnecessary measure that will end up hurting employment and growth. There are really two pieces to this argument. First, there’s the idea that the economy is now flashing warning signs for a recession, so it’s time for the Fed to stop hiking. Second, some argue that the Fed’s rate hikes in 2022 haven’t even had time to affect the economy yet, so the fall in inflation can’t possibly be the Fed’s doing, and hence the Fed’s tightening has been (partly or entirely) superfluous. So let’s talk about both of these ideas.

Are we headed for a recession?

The answer to this question, by the way, is “No one really knows”. Not just now, but always. There are some suggestive indicators that tell us when the probability of a recession is elevated, but the signal is very weak; there’s no macroeconomic model in existence that can know with a high degree of certainty whether a recession is imminent.

As a case in point, it’s useful to remember the late 2010s. Those were boom times, and yet many in the commentariat — including many economists — thought that a recession was right around the corner. Obviously the coming of the pandemic in 2020 makes it impossible to tell whether late-2019 recession forecasts would have come true, but in fact, people were talking about an imminent downturn as early as 2018. Much of the worry focused on corporate debt, which was the only sort of private-sector debt to grow in the years following the Great Recession.

Then in late 2018, the yield curve inverted — meaning that long-term interest rates fell below short-term rates. The talk of recession exploded, because an inverted yield curve is a decent predictor of slowing economic activity. And yet by the time Covid struck over a year later, there had been no recession, or even anything close to one — in fact, hiring was accelerating in January and February of 2020.

I definitely see some similarities between now and then. The labor market is still very strong — U.S. payrolls added 223,000 jobs in December, which is a very strong performance for an economy supposedly on the brink of recession. My favorite measure of labor market strength, the prime-age employment-population ratio, is still right around 80%, which seems like its long-term ceiling:

Consumer sentiment increased as well.

So where might we find signs of an imminent recession? Data on economic output comes out quarterly, and thus we don’t know exactly what happened in late 2022 yet. But private investment did fall in the 2nd and 3rd quarter of 2022, and exports fell in the 3rd quarter. Consumption grew a little bit, but if the slowdown in investment and exports continues, we would expect consumption, employment and growth to eventually fall.

But anyway, lots of people are worried about a recession in 2023. One reason, as in 2018, is the inverted yield curve. Many economic studies predict that when long-term rates are lower than short-term rates, the probability of a recession is much higher.

And whereas long-term rates barely went below short-term rates back then, this time the inversion has been massive since summer 2022:

This is the biggest and most protracted inversion we’ve seen since the 80s, when Paul Volcker raised rates to very high levels and caused two sharp recessions.

Let’s take a second and review why an inverted yield curve would predict a recession. Basically, when long-term interest rates are lower than short-term rates, it means that markets expect short-term rates to fall over time. That could mean that A) rates will come down because they’re especially high right now relative to their “natural” rate, and high rates tend to choke of economic activity, and/or B) the real economy will slow in the future, which lowers interest rates all on its own.

In any case, economists generally believe that a yield curve inversion is a good predictor of recession. For example, economists like Campbell Harvey managed to predict the 2008 recession using the yield curve:

But by the official NBER definition, or by GDP-based indicators, by the time Harvey made this prediction the U.S. economy had already been in recession for several months. So unless we see really huge data revisions in the coming months, that just isn’t the case right now.

Then there’s that nagging case of 2018-19. Due to Covid, we’ll never really know if that yield curve inversion really would have presaged a recession, but it had already been over a year and the economy was still going strong. And some economists have argued that the yield curve’s predictive power is weaker than it used to be.

If inflation gets defeated via the mechanism of lower inflation expectations, without the need for actual demand destruction, the economy might escape a recession and the Fed would lower rates because inflation had been defeated. That would be consistent with an inverted yield curve. Alternatively, maybe market expectations are just wrong, and the inverted yield curve is just bond traders making a mistake.

So we’re in this weird moment where both our theoretical intuition and our traditional leading indicators say that we should be either in a recession right now, or headed for one very soon. And yet all the macroeconomic data continue to look strong. So either the economy is like Wile E. Coyote and has fallen off a cliff without realizing it yet, or the prediction methods that worked in the past aren’t as useful anymore.

Anyway, that brings us to the equally difficult question of whether the Fed is going overboard.

Is the Fed doing too much?

In the early days of the post-pandemic inflation, there were people who called themselves Team Transitory, who argued that inflation was due to supply chain snarls and would subside on its own. That was always dubious — the booming job market made it seem likely that positive demand shocks (from easy monetary and fiscal policy) were also a big factor. And as supply chain snarls worked themselves out but inflation failed to subside, that idea started to look a bit silly. The Fed itself certainly seemed to abandon Team Transitory, and started hiking rates in March 2022.

But now the monetary doves — the people arguing for the Fed to stop or reverse its rate hikes — are sounding quite Team Transitory-ish. For example, my podcast co-host Brad DeLong believes that there’s no way that inflation could be falling because of the Fed’s rate hikes, because rate hikes take over a year to have an effect. Thus, inflation must be subsiding on its own, meaning that further Fed hikes will be going too far. In the latest episode of our podcast, he debated with my PhD advisor Miles Kimball, who wants the Fed to raise rates more:

And on January 11th, columnist Kevin Drum wrote:

The Fed is not winning anything and the patient hasn't been given any medicine yet. Nothing that's happened in the past year is related to Fed activity in any way. I assume that even the hard core forward guidance folks agree that six or seven months is far too short a time for the Fed's interest rate hikes to have affected the economy…If inflation keeps going down and then the economy crashes midway through the year, the Fed will have proven itself about as competent as a Russian general.

In fact, DeLong and Drum are backed up by a fair amount of research. Lots of studies find that it takes 2-3 years for interest rate hikes to have an effect. And when you look at the history of the U.S.’ most famous monetary tightening — the conquest of the 1970s inflation — you can see that it was about three years from when rates began to rise (which was even before Volcker) until inflation started to fall:

But to say — as Drum does — that the research literature is fully in support of long monetary policy lags is just not right. Havranek and Rusnak (2013) surveyed the literature and found that studies are divided into two types — those that predict a hump-shaped (i.e., temporary) effect of rate hikes on inflation, and those that predict a gradually increasing impact. It’s natural that studies don’t agree on this, because estimating this lag requires a lot of strong assumptions about the economy works, and different assumptions lead to very different conclusions. The “hump-shaped” studies find that most of the response to a rate hike happens in the first 6 months:

So it really depends on what assumptions you make here. The short version is that if you assume that if expectations matter a lot, then you get a much faster response — as soon as businesses see the Fed start to hike, they know that either inflation will go down or the Fed will just keep hiking til it does, so they go ahead and lower their prices immediately. On the other hand, if you assume that expectations don’t matter very much, then rate hikes can only work by making investment more expensive, which reduces investment, which reduces hiring, which reduces consumption, which reduces prices…which takes years.

To make things even more complicated, it’s possible that the monetary policy lag actually changes over time. In fact, Doh and Foerster of the Kansas City Fed have a new paper arguing that the role of expectations has increased in recent decades, meaning that rate hikes act a lot faster than they used to — maybe in as little as 2 to 4 months.

So DeLong and Drum are not on solid empirical ground when they claim that the Fed’s rate hikes had no effect on inflation; indeed, in macroeconomics, there is almost never any solid empirical ground to be found.

I should also mention the possibility that fiscal policy is playing a big role here too. We ran huge deficits in 2020 and early 2021 to get people through Covid. People saved up a lot of that cash and spent it in 2021 and 2022, which many people think contributed to inflation. But fiscal deficits started closing in late 2021 as pandemic relief dried up:

And disposable personal income stopped being anomalously high around this same time. So it could be that part of the inflation decrease comes from the fiscal austerity that began a year and a half ago.

So anyway, we don’t really know for sure whether the Fed and/or the Biden administration and Congress get much credit for the moderation in inflation over the last few months. But it seems like a safe bet that as long as the trend continues, the Fed will taper off its rate increases. One way or another, the conquest of the post-pandemic inflation is underway.

What isn’t transitory is the tight labor market. Long-term demographics show that we’re going to be in a labor shortage for 20 years. Fed policy, economic models, etc. won’t solve this. The high-tech sector may be at an inflection point but it will be the high-tech sector (AI, automation, high-end manufacturing) must take up the slack in the labor market. The age-participation numbers are already set in motion. Unless we significantly increase immigration (politically infeasible with a gridlocked, coin-operated Congress), the burden/challenge falls to high tech.

During the whole section about "how long it takes" I was rolling my eyes and whining "come ON! What about the Doh and Foerster paper!"

... And then you mentioned it lol

In general I think everyone (academics, laypeople, pundits) underestimate how often systems lack any kind of "long run average". We crave a kind of certainty and predictability in the world that often just isn't there.