Senator J.D. Vance caused a bit of a stir on Twitter the other day by claiming that immigration is responsible for rising rents in the United States:

First of all, it’s worth noting that the Axios data — which shows rent outstripping income — isn’t necessarily the right data to use here. Using the BLS’s numbers for rent inflation (which are adjusted for the size and quality of housing) divided by median personal income, I find that rent has actually become generally more affordable in the U.S. over the last few decades when immigration was high:

In other words, to the degree that rents have risen since 2010 or so, it’s because people are renting bigger places with more air conditioning and other expensive amenities.

Also, Vance talks about a wave of immigration being responsible for pushing up rents. But in fact, what should matter for housing demand isn’t the number of immigrants — it’s the total number of households. And here there just hasn’t been much change. The number of new households that the U.S. added each year in the 2010s was actually lower than in the 70s, and about the same as in the 80s and 90s:

So the basic picture that Vance paints — a wave of immigration swamping our rental markets — just can’t be true. Immigration has merely compensated for decreased natural population growth in the U.S., which should keep overall national housing demand pretty constant. And indeed, once you account for things like house size, rents don’t seem to have increased at the national level.

Therefore, I wouldn’t lose much sleep over the chart that Vance posted.

That said, there are some legitimate concerns about the effect immigration has on housing markets, especially at the local level.

Why immigration can strain big-city housing markets

Immigration is just like any population increase — it pushes up demand for housing, without automatically increasing the supply. You can make a fancy model for how this works, but ultimately it’s pretty simple — more people means more demand, demand pushes up price unless supply also goes up.

(Note: this means immigration will affect housing markets differently from how they affect labor markets. Recall that immigrants raise both labor supply and labor demand, which is why studies don’t show much effect of immigration on the wages or employment of the native-born, or even show a positive effect in some cases. But with housing, more people, be they immigrants or locally born babies, don’t automatically come pre-packaged with new housing.)

So if immigrants flood into a city, one or more of these three things will generally have to happen:

The city builds new housing to accommodate the newcomers.

Existing residents move out of the city.

Rents and house prices go up.

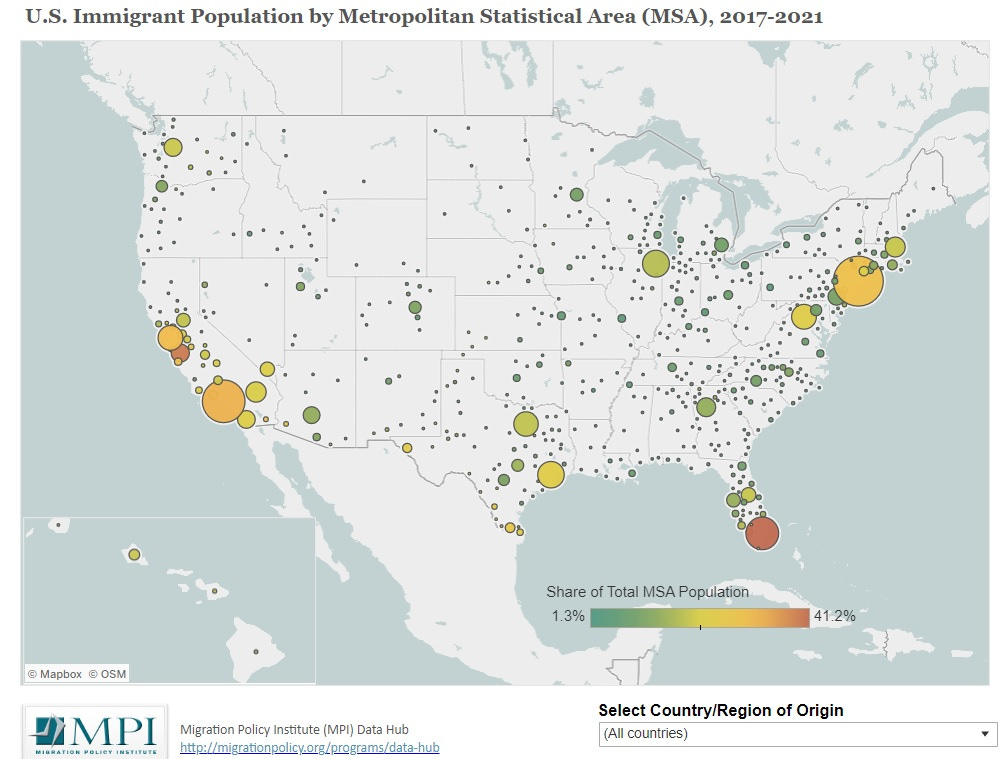

A lot of people responded to Vance’s tweets by saying “Just build more housing!” But it’s easy to see why that’s an unsatisfying response. First of all, the U.S. political economy already struggles to build housing. Second, immigration tends to be concentrated in a few big cities:

We probably can’t expect these few big cities, all on their own, to build enough housing to accommodate the entire national inflow of immigration. Thus, we probably should worry somewhat about the dynamic where immigration raises local rents in big cities, this causes locals to move out, and the people who get pushed out get mad and start to vote for anti-immigration politicians.

How much should we be worried about this? Well, probably not a lot! Remember that studies show that immigration generally leaves native-born real wages unchanged. Real wages account for the cost of housing. So even taking the increase in housing costs into account, immigration isn’t actually making native-born people poorer…on average.

On the other hand, almost none of those immigration studies were done in a modern American “superstar” city in the 2000s and 2010s, so the general increase in demand for housing in these cities, combined with their unusually NIMBY-fied political economy, could make them special cases. And remember that even if immigration doesn’t make native-born people poorer on average, it can still hurt some people, who may then move out of town and start voting for Trump-type politicians.

That last point is a reminder that immigration’s effect on local housing markets could also contribute to local inequality. When immigrants buy houses — typically from the native-born — it represents a wealth transfer from those immigrants to the native-born. But when immigrants rent, the increased demand raises the income of landlords and decreases the real purchasing power of native-born renters.

And when we look at population changes in U.S. cities, we see that in the late 2010s, big cities lost population to domestic migration, and gained population only because immigration more than made up the difference.

The pattern was especially noticeable, and started earlier, in New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago.

So although immigration isn’t creating housing problems at the national level, it might be straining the housing markets in a few big cities. It’s not a huge problem, and it certainly doesn’t come close to outweighing all the good that immigrants do for America. (Nor is it a problem for J.D. Vance’s own constituents.) But we should think about how to solve it, anyway.

Two solutions: Immigrant diffusion and place-based visas

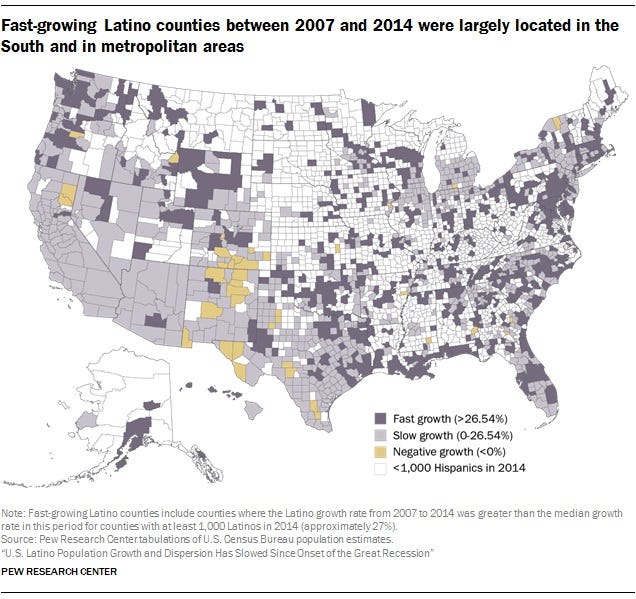

The first solution to the problem is just to wait. The pattern with immigrants is that they start off moving to a few big cities and ethnic enclaves, and then they and their kids and grandkids eventually they disperse throughout the country. The recent waves of immigrants are following this pattern to a T. For example, Latinos used to cluster very strongly in California and the Southwest, but in the 2000s and 2010s they started moving to the rest of the country:

This will eventually help equalize immigration patterns. Because people tend to immigrate to places where there are others of the same ethnicity (or even family and friends already living there), the spreading-out of Latino Americans throughout the country will also lead to a diffusion of immigrant destinations over time; more Mexican and Central American people will immigrate to the Midwest, South, or East instead of to the Southwest.

And that will help revive declining towns in the American heartland. Here’s a map showing how immigration overcame native population loss in the Plains states in the 90s and 2000s:

Rents are a big problem if you live in L.A. or NYC or San Francisco. But in much of the country, it’s decline that’s the bigger problem by far, as locals move to the coasts and towns empty out. Immigration, and diffusion of immigrants and their kids from traditional ethnic enclaves, is the main force that can arrest that decline.

This is a trend that the government should try to speed up, not just to spare the housing markets of New York and Los Angeles, but to accelerate the demographic revival of the heartland. One way to do this is with place-based visas, which encourage immigrants to move to the places where the local economy could use the biggest boost. The Economic Innovation Group, a think tank, managed to persuade the Biden Administration to embrace the idea of a “heartland visa” pilot program, and even some conservatives have voiced their support. The government could also create vouchers for immigrants to move to special designated areas to shore up local population loss.

In other words, immigration is a good thing for America overall, but it has the potential to be a very good thing for places like J.D. Vance’s Ohio, which attracts relatively few immigrants or domestic movers, and whose population has largely flatlined since the 70s:

It’s nice of Vance to be so concerned for renters in big blue cities in coastal states. But in terms of helping his own constituents, more immigration represents nothing but upside.

1. Canada has a great provincial nomination system for immigration. It can work here.

2. Vance is being unserious and Noah should stop wasting time on his bullshit.

3. Ask Vance about building more housing and watch how he flips into full NIMBY mode.

It's funny to talk about "heartland visa" as if the coastal states didnt have large semi-rural and rural areas that face exactly the same kinds of problems as Ohio does. There is a funny misconception that everyone on the coast lives in the big cities or their immediate suburbs - probably no more true than everyone in Georgia lives in Atlanta.