Is conflict with China fueling anti-Asian attacks?

Probably not yet. But we should still use every tool we can to make sure it doesn't.

Here’s something that keeps me up at night. I’ve always been a little bit of a China hawk. Back in the 2000s I was heavily skeptical of the idea that opening up trade with China would make them less authoritarian, and I already worried about the impact on American workers (both fears turned out to be justified). In recent years I’ve become alarmed at China’s crushing of Hong Kong and its increased aggression toward neighboring countries, and both have caused me to speak out more against the Chinese government; meanwhile, the persecution of the Uighurs, whether or not it amounts to a genocide, seems to suggest that the leadership in China has taken a darker, more authoritarian turn.

But at the same time, I’ve been dismayed at the massive increase in violence and harassment against Asian Americans. And I’ve wondered if there’s a connection between U.S.-China conflict and that outbreak of racist aggression. In fact, one of my first Bloomberg posts, back in 2014, was about the possibility that this might happen:

The "coming war with China" feels like the Sword of Damocles hanging over the head of Chinese-Americans.

The U.S. has a bad record when it comes to this sort of thing. The most famous and shameful example, of course, is the mass internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II -- just read "Star Trek" actor George Takei's account of growing up in a U.S. concentration camp. But it isn't the only example…

Our leaders haven't been vocal enough or persistent enough in saying that this is a multiracial country[.]

Now it seems like my fear might have come to pass. And even worse, there are a few people out there who accuse me of feeding the hate:

Now, this person is a tankie who says a lot of very ridiculous things on Twitter. I don’t take them seriously (in fact, I blocked them). But I do take the allegation seriously, because I do worry that hawkish rhetoric on China is contributing to anti-Asian hate. You’d have to be a complete fool to look at history and not worry about international conflict causing violence against minority populations. And when we look at the violence against Asian Americans, it’s clear that it’s very real and racially motivated, and that it coincides with a hardening of attitudes toward China around the world.

The question then becomes: What do we do about it?

The increase in anti-Asian violence is real, and it is racial

Every time I tweet about the anti-Asian attacks, a couple of Twitter “reply-guys” pop up to question whether it’s actually a real increase, or whether it’s racially motivated. People just really don’t want to believe that a wave of racist, xenophobic violence could be a real thing in the America of 2021. And of course if you want to stick your fingers in your ear and go “LA LA LA, CAN’T BE REAL”, then of course you can do that — in fact, Americans have become quite adept at sticking our fingers in our ears and blocking out unpleasant truths. But the truths are still out there, regardless.

There was a 150% increase in reported anti-Asian hate crimes in American cities in 2020 (by some measures, the total number of reported violent incidents was about 3000). That’s compared to a 30% rise in murder and a 6% rise in aggravated assault. Violent crime has obviously surged during a year of pandemic, social unrest, and economic devastation, but the rise in anti-Asian hate crimes is far bigger — about 5 times as big as the rise in murder and 25 times as big as the rise in aggravated assault. In Vancouver, Canada, reported anti-Asian hate crimes rose from 12 to 98, an 8-fold increase, and there’s also a reported increase in Europe. (That shows that the wave of hate stretches far beyond America’s borders, which casts heavy doubt on the idea that Black-Asian racial tensions are behind the violence.)

These numbers are just too big to be part and parcel of an overall increase in violent crime.

And although “you can’t PROVE it’s racial!” is a perpetual rallying cry among the fingers-in-ears types, tons of corroborating evidence suggests a massive wave of increased animosity toward Asian Americans in the past year. Interviews with kids report a substantial rise in racial bullying, often related to COVID. A study found that media use of the term “Chinese virus” was associated with an increase in measures of implicit bias toward Asians, which was more pronounced among conservatives (who tend to hear the term “Chinese virus” and similar terms much more often in their media outlets). Meanwhile, someone bombed a Chinese community center in Nebraska, anti-Asian racist graffiti abounds, researchers report a big increase in anti-Asian rhetoric online, and some people have actually declared their specific intent to attack Asian people!

Now, the fingers-in-ears crowd might say that anecdotes are anectodes, qualitative research is qualitative, implicit bias tests have plenty of problems, graffiti can be faked, and reports of abuse can’t be independently verified. But we’ve clearly entered the region where the burden of proof is on the denialists to show why there isn’t an outbreak of violent racially motivated anti-Asian hate crime.

Until someone comes out with some very convincing evidence pushing back on the notion that the wave of anti-Asian hate is real, we should regard it as a very real problem in need of immediate solutions.

Attitudes toward China have turned sharply negative

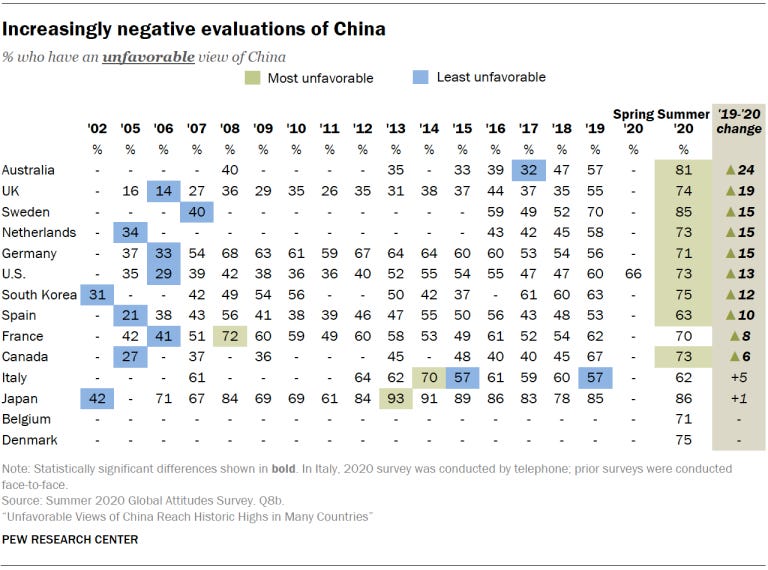

Now let’s look at attitudes toward China. The best data I know come from Pew, which does very large-sample studies with lots of face-to-face interviews. Their data shows an enormous spike in unfavorable opinions of China:

Now, this is only developed countries, because in the time of COVID it was hard to do face-to-face interviews in developing countries. But other data suggests that a similar hardening of opinion is underway in Southeast Asian countries.

The obvious cause would be COVID itself — even if the press refuses to say the name “Wuhan”, but everyone in the world knows that the virus originated in China. Whether or not it makes sense to blame China for failing to suppress the virus or warn the world earlier, it’s clear that many people do blame China. In the U.S., fully half of people say that we should “hold China responsible” for the role it played in the pandemic, whatever that means.

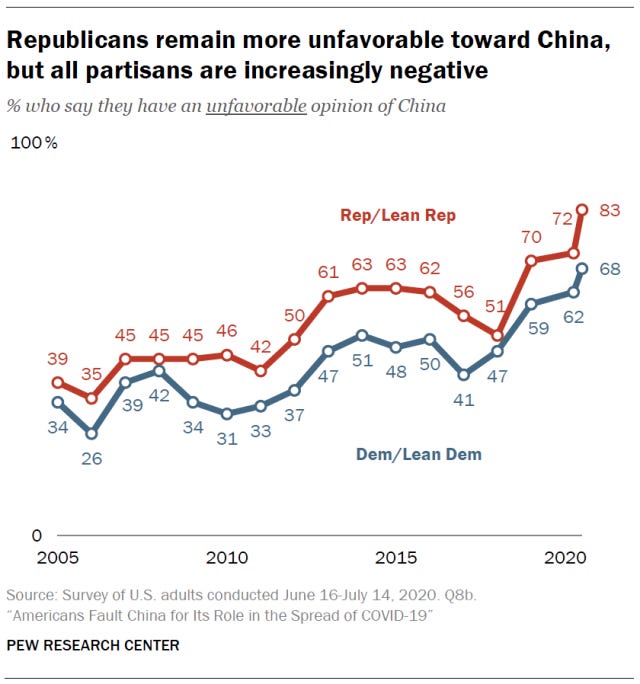

Nor does this attitude shift seem like a pure effect of Trumpian rhetoric. Yes, Trump loved to say “China virus”, and conservative media is full of terms like that. But Democrats, who on most issues tend to go the exact opposite direction from Trump, have also soured on China:

Nor should we expect Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany, Australia, etc. to think what Trump wants them to think, especially because they have very poor opinions of Trump as well!

So it’s not just Trump making people mad at China. But is it just COVID? Here are Pew’s numbers, broken down by year:

There was certainly a big negative swing in the year of the pandemic. But there were also pretty substantial negative swings across the board in 2019, before anyone knew COVID existed. Here are the increases in negative opinion toward China from 2018 to 2019:

Australia: +10%

UK: +20%

Sweden: +18%

Netherlands: +13%

Germany: +2%

U.S.: +13%

South Korea: +3%

Spain: +5%

France: +8%

Canada: +22%

Italy: -3%

Japan: +7%

And though the data is patchier, it looks like there were substantial increases in negative opinions of China in many countries well before Trump ran for President. Negative sentiment toward China was at its lowest before the Great Recession, and seems to have ticked up in the U.S, UK, and Japan in the early 2010s around the time that Xi Jinping took power.

So while COVID seems like a factor, the timing is wrong for this to just be COVID. Other possibilities include:

Fear of China’s economy

China’s crackdown on Hong Kong and repression of the Uighurs

Increasing military tensions (South China Sea, etc.)

The timing seems off for the “fear of China’s economy” explanation. China’s growth was very fast before the Great Recession, but has slowed substantially since then.

I could see people being scared of how much better China’s economy did in the pandemic, thanks to its effective suppression efforts. But that doesn’t explain 2019, or the earlier increases either. And with Chinese labor costs much higher than a decade ago and rising steadily, the competitive threat to workers in the developed world has receded.

That leaves geopolitical tensions and human rights abuses. The parsimonious explanation for rising anti-China sentiment is that China is an increasingly powerful superpower that also looks both increasingly authoritarian and illiberal and increasingly aggressive territorially. People don’t like big scary countries (this applies to the U.S. as well), and China is bigger than ever and looking scarier than before.

And what about the link between anti-China sentiment and hate crimes against Asian Americans? The big worldwide uptick in negative opinions of China in 2019 didn’t apparently coincide with any wave of anti-Asian racial violence. For example, here’s the NYPD’s numbers from September 2020:

The FBI shows 158 anti-Asian hate crime incidents in 2019 compared to 148 in 2018 and 140 in 2014 (before Trump). They don’t have 2020 numbers yet, but it definitely looks like the big increase is 2020-specific, even though people around the world were souring on China in 2019.

Obviously this data doesn’t prove that anti-China sentiment over geopolitics and human rights is unconnected to anti-Asian hate crimes. Maybe the effect happens with a lag. Maybe conflict with China didn’t create anti-Asian hate before, but is now interacting with misplaced anger over COVID in some complex way. Etc., etc. But it does seem to suggest that COVID, rather than Hong Kong or Xinjiang or the South China Sea or the trade war, is the thread connecting anti-China sentiment to anti-Asian racism.

Specific forms of violence are self-sustaining memes

I should mention my own hypothesis for why anti-Asian racial violence is exploding. Misplaced anger over COVID seems like the obvious instigating factor. But I suspect that anti-Asian violence then became a self-sustaining meme — just like other waves of violence.

An example is the big rise in Islamophobia in 2015-17. In the U.S., attacks on Muslims during the early Trump Era exceeded those in the wake of 9/11. Most of the high-profile incidents were during this period. But after early 2017, Islamophobic attacks began to fall at a rapid pace.

Another example is the giant wave of terrorism in the U.S. in the late 60s and early 70s. Most of that violence was nonlethal (bombing of empty buildings), but size of the peak in the early 70s, and the rate decline afterwards, is just incredible.

A third example is the trend of high-profile mass shootings that arose in the 2010s. It didn’t get any easier to go shoot a bunch of people, nor was there any political connection between most of the various incidents. Some researchers believe that many of these were copycat crimes — when one mass shooter gets a lot of attention in the media, it makes other violent, unhinged people want to do the same thing so they can get attention too.

So my theory of anti-Asian violence is that misplaced anger over COVID kicked it off (perhaps aided by Trumpian rhetoric), but it became a self-sustaining meme. Violent people looking for someone to attack — whether because of pandemic stress, natural aggression, a desire to rob someone, a yearning to find someone to hate and exclude, or whatever — zeroed in on Asians as potential victims instead of looking elsewhere.

Because memes like this can be self-sustaining, the violence and hate threatens to outlast Trump. And even if geopolitical tensions with China didn’t give rise to the anti-Asian meme in the first place, they might end up sustaining it or reigniting it. At least, we can’t rule out the possibility. So we have to use every trick in the book to make sure that doesn’t happen.

The return of “racial liberalism”?

If you haven’t read Ellen D. Wu’s “The Color of Success: Asian Americans and the Origins of the Model Minority”, you really should read it. The book chronicles the history of what the author calls “racial liberalism” — official attempts by the U.S. government to paint Asian Americans in a positive light.

Interestingly, these attempts began during the Depression, under FDR, even before World War 2. But they accelerated during the war, when China was a key U.S. ally in the fight against Japan. The Roosevelt Administration and media outlets made concerted attempts to humanize and praise Chinese Americans, in order to combat the pervasive anti-Chinese racism that existed on the West Coast. Interestingly, in the later years of the war, this hagiographic approach was extended to Japanese Americans, who by then were joining the U.S. Military in significant numbers; Japanese Americans, though they had only recently been mass interned and dispossessed, were painted as noble, heroic, etc. in official government propaganda.

During the early days of the Cold War, when China was a U.S. opponent (rather than a de facto ally as it would later become), the U.S. government consciously promoted an Asian American identity — which looked surprisingly like modern multiculturalism — as part of an effort to distinguish “our” good Asians from “their” bad ones. This didn’t stop suspicion from being directed at Chinese Americans on the West Coast, but it probably prevented the kind of mass hatred and systematic discrimination that was directed toward Japanese Americans at the beginning of WW2.

Obviously these past efforts by the U.S. government to tell Americans not to hate Asian people were ham-handed propaganda that would look painfully dated to modern sensibilities. But they offer the possibility that a modernized form of “racial liberalism” could quash the meme of anti-Asian violence. (Side note: Though the title might imply it, the “racial liberalism” of WW2 and the early Cold War was not anti-Black; comparisons between Black and Asian Americans were weaponized later, mainly by conservatives, during the Civil Rights movement and afterwards. FDR and Truman also pushed for more positive perceptions of Black people, as illustrated by the 1947 propaganda film “Don’t Be a Sucker”, which helped promote the integration of the U.S. Military.)

Already, the Biden administration is making moves in this direction. On January 26th, the President released a memo announcing a broad-spectrum effort to combat racism against Asian Americans. Some excerpts:

The Secretary of Health and Human Services shall, in coordination with the COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force, consider issuing guidance describing best practices for advancing cultural competency, language access, and sensitivity towards Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the context of the Federal Government’s COVID-19 response…

Executive departments and agencies (agencies) shall take all appropriate steps to ensure that official actions, documents, and statements, including those that pertain to the COVID-19 pandemic, do not exhibit or contribute to racism, xenophobia, and intolerance against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders…

The Attorney General shall explore opportunities to support, consistent with applicable law, the efforts of State and local agencies, as well as AAPI communities and community-based organizations, to prevent discrimination, bullying, harassment, and hate crimes against AAPI individuals, and to expand collection of data and public reporting regarding hate incidents against such individuals.

In other words, Biden has placed the U.S. government firmly on the side of Asian Americans, not just with words but with concrete actions.

Civil society, too, is mobilizing on behalf of Asian Americans. Jennifer Lee and Tiffany Huang report on grassroots efforts to protect Asians from violence:

This is a moment of reckoning for all Americans—not only Asian Americans—to reimagine what safety, belonging, and justice could look like. We are already seeing signs of this. Hundreds of Americans are volunteering to escort elderly Asian Americans to help them feel safe, and hundreds more gathered over the weekend at a rally in New York to protest anti-Asian violence. When neighbors learned that an Asian American family with two young children in Orange County, California was being harassed repeatedly by a group of teenagers, they organized to stand guard each night to protect them and their home.

This won’t completely prevent anti-Asian attacks. America is a huge country with a lot of anger and a lot of violence, and neither the U.S. government nor community defense organizations can be everywhere at once. But hopefully it will send a message to all the violent people out there that Asian Americans are not some special category of people that it’s OK to attack.

In fact, more efforts like this might be needed in the near future. The U.S. is simply not going to appease China’s territorial ambitions or look the other way regarding its human rights abuses just to reduce the risk of racism at home. Indeed, Biden’s policy stance toward China is arguably tougher than that of his big-talking predecessor.

Official government actions to protect Asian Americans, both in rhetoric and in deed, will be necessary to prevent tensions with China from reinforcing or rekindling the anti-Asian meme. The U.S. probably can’t avoid tensions with China, but it must not repeat its mistakes of the early 20th century — national conflicts can’t be allowed to spill over into racial persecution.

It's not just the virus it's things like this. China is acting very authoritarian not just inside China but also towards other states and it's coming back to bite them.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2020/01/21/chinas-ambassador-sweden-calls-journalists-critical-beijing-lightweight-boxers-facing-heavyweight/

I know language policing is never a full solution to anything but I wonder if it would be worthwhile to talk about the Chinese Communist Party's human rights violations, about the CCP's territorial ambitions, about Biden being tough on the CCP.