Is China's catch-up growth over?

The development star has been hit by a perfect storm of headwinds

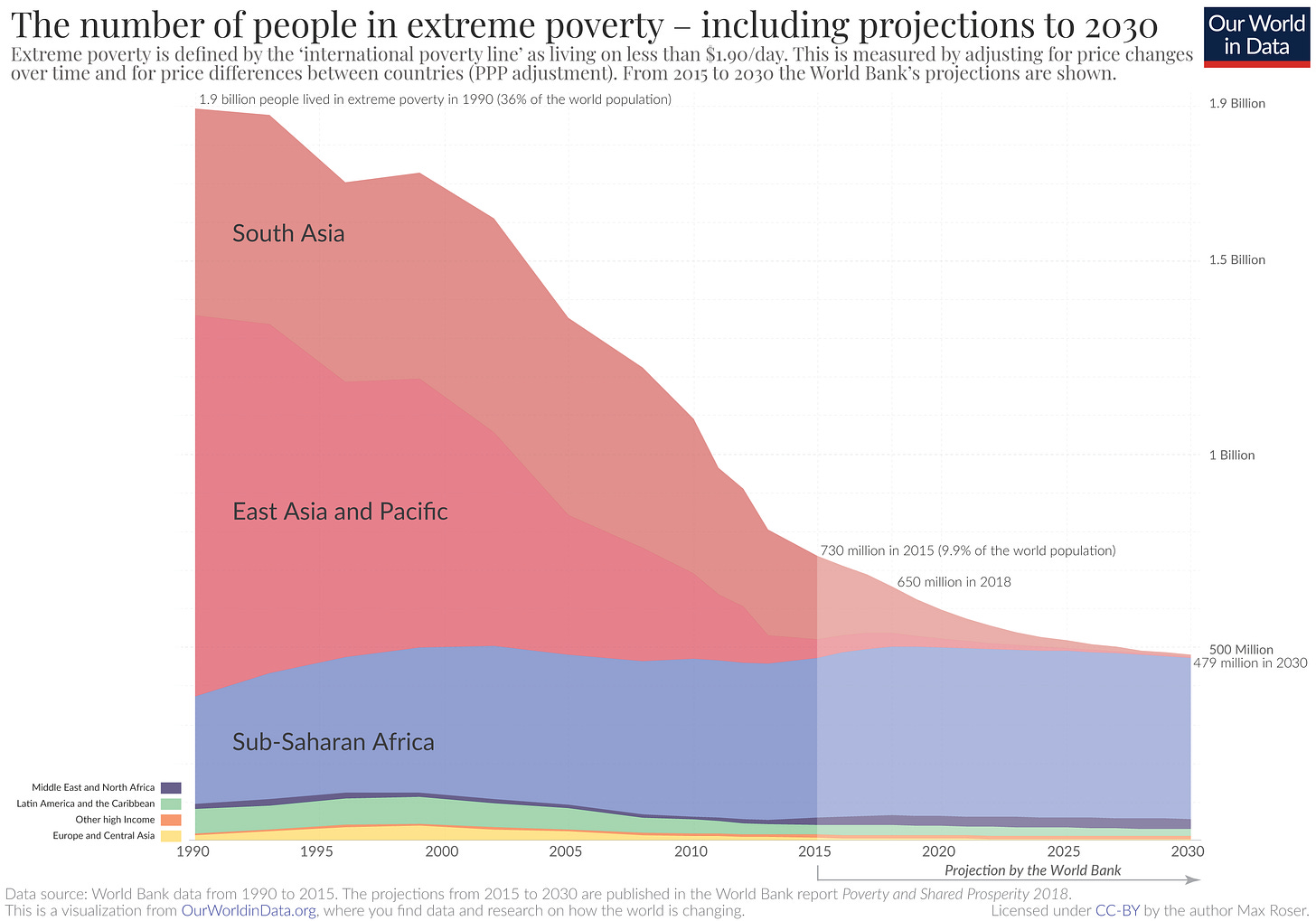

There is no doubt that China’s catch-up growth has been one of the most impressive feats of economic development in world history; the only other contender would be the Industrial Revolution itself. In just 40 years, the country lifted itself from utter destitution to average income status, pulling hundreds of millions of people out of dire poverty.

It’s difficult to overstate what a huge feat this was. It involved a combination of market-based reforms, effective governance, and (mostly local) industrial policy. It reshaped the industrial landscape of the globe and changed world history forever.

But all things come to an end. Every other spurt of rapid development has eventually slowed to the stately pace of a mature economy. There are basically two reasons this happens. First, as you build more physical capital — more buildings, roads, railways, machine tools, vehicles — the added output of each new piece of capital goes down, while the upkeep costs just keep rising. This is the basis of the famous Solow growth model, and we’ve seen this happen again and again to fast-developing countries. The second reason rapid growth peters out is that it’s easier to copy existing technologies from other countries than to invent new ones yourself.

The real question is when this slowdown happens. Japan’s history provides an interesting example here. Here’s a graph of Japan’s income per capita (at purchasing power parity) as a fraction of America’s:

You can see that Japan’s catch-up (at least, post-WW2) really happened in two phases. There was rapid catch-up until the early 1970s, then a few years where catch-up paused, then a resumption of catch-up at a slower pace for about 15 more years. After the bursting of the country’s famous land bubble, its economy actually lost ground to the U.S. (rapid population aging was also a big part of this), and settled in at around 75% of U.S. levels (fairly standard for a medium-sized developed country).

Economists have found that this pattern is very typical. In a pair of famous papers in 2012 and 2013, Barry Eichengreen, Donghyun Park and Kwanho Shin found that fast-growing countries tend to slow down when they reach a certain income level. In the second paper, they write:

[N]ew data point to two [points where catch-up growth slows down], one in the $10,000-$11,000 range [of per capita GDP (PPP) in 2005 international dollars] and another at $15,000-$16,0000. A number of countries appear to have experienced two slowdowns, consistent with the existence of multiple modes. We conclude that high growth in middle-income countries may decelerate in steps rather than at a single point in time.

Of course, these numbers probably aren’t fixed in time; as the developed countries get slowly richer, the ceiling at which newly developing countries top out rises as well. Eichengreen, Park and Shin also find that slowdowns tend to happen when a country reaches 75% of U.S. income levels.

China has already experienced its first growth slowdown, and it was right around the first level that Eichengreen et al. predict. In the early 2010s, China’s growth decelerated from about 10% to about 7%:

It’s pretty startling how well the economists’ model predicted both the timing and the size of that slowdown. The reasons for the growth decrease are pretty well-documented — the Lewis turning point (where surplus rural labor dries up), the end of the demographic dividend, the stagnation in developed-country export markets after the financial crisis, etc.

7% growth is still pretty fast, though, and by 2020 China had reached the income level where Eichengreen et al.’s model predicts a second slowdown. We won’t know for years whether China has slowed a second time, both because Covid is distorting the numbers and because China’s government will probably smooth out a few bad years of data as it has in the past. But there are signs that a perfect storm is brewing that could lead to a permanent deceleration. And depending on the size of that slowdown, it could mean that China’s economic miracle has basically run its course.

A perfect storm

China is being hit by four simultaneous economic problems. These are:

A real estate crash

An electricity crunch

Xi Jinping’s industrial crackdown

Delta Covid, combined with China’s zero-Covid policy

Let’s look at each of these in turn. First, China’s real estate woes are by now well-known, and I’ve written a lot about them. But a couple months after everyone was focused on Evergrande, the problems are still ongoing (Bloomberg, btw, is the best source to follow to keep up with that story). The property sector, which makes up a ridiculously large percent of China’s economy, is slowing down:

One important point here is that the Chinese real estate crash won’t look quite like the Japanese and American crashes in previous decades. Those were mainly about falling land prices. In China, prices are falling, but only modestly, and they never reached the ludicrous heights that they did in Japan or the U.S. That reflects the fact that the U.S. and Japan basically had (and have) market-driven financial systems, where land prices were the link between real estate and the rest of the economy. In China, in contrast, the links have more to do with state-mandated lending to property-related industries, and with local government dependence on revenue from real estate sales.

It’s a lot harder to predict how a slowdown will filter through the economy that sort of opaque, state-heavy system. But it’s clear the problems are systemic; more and more big important real estate companies are revealing deep distress, and defaults are rising. As of a month ago, Chinese developers accounted for half the world’s distressed debt. The government has taken some halting steps to reflate the real estate sector, but it’s clear that policy is being restrained by the government’s desire to reduce the importance of the sector in the Chinese economy. And companies all know that. Thus, we’ve probably reached the end of the line for the era when China made and all economic problems vanish by pumping up real estate.

Next, there’s the electricity crunch. A combination of regulation, pandemic-driven supply disruptions, and a government attempt to shift away from coal power hit China hard in September and October. That crunch now looks to be easing, but only because China started burning a lot more coal (much of it imported). But this is just an unsustainable strategy. China is already the world’s biggest coal user by far, and produces more greenhouse emissions than the entire developing world combined. Eventually coal exporters will come under increasing pressure not to ship their coal to China, for the sake of the planet. And as the climate change problem increasingly becomes a China problem, there will be more pressure for the country to resume its efforts to curb coal use — from self-interest if nothing else.

China’s third growth headwind is Xi Jinping’s crackdown on industries he doesn’t like, including consumer internet companies, private education, and various entertainment industries. The basic idea, as everyone pretty much accepts now, is to prevent China from becoming a decadent post-industrial society, and force it back toward being a martial, manufacturing-oriented nation.

The problem here is that the crackdowns are being driven by one old conservative Boomer’s idea of what a tough strong society should look like, rather than by any sort of consistent economic theory or precedent or transparent decision-making process. That means that no one really knows where the hammer is going to strike next. And that’s going to chill entrepreneurial activity in sectors far beyond the locus of the initial crackdowns — even ones that Xi has every intention of leaving alone. Companies and entrepreneurs simply don’t know which activities the old Boomer-cons of the CCP will decide are a source of national weakness — so why take chances?

Finally, there’s Covid. Back when the original virus had an r_0 of 3, countries like China, Australia, South Korea, Taiwan, and New Zealand did very well economically by simply containing the virus. But now that Delta Covid has evolved to have an r_0 of 6, those zero-Covid strategies simply aren’t possible anymore. Most countries that had relied successfully on containment are now shifting to mass vaccination and a “live with Covid” strategy, but China’s government seems intent on trying to save face by keeping the policy in place forever. As a result, we’re seeing China resort to increasingly desperate measures to contain a virus that seems to have evolved past the point of containment.

Now, I said “finally”, but there might be even more shocks on the way. Another might be fear of war. Shuli Ren writes:

An official statement urging local authorities to ensure there was enough food this winter prompted a social media frenzy, with people linking it to a possible war with Taiwan. In the last month, tensions between China and the U.S. increased over the island…These days, Chinese investors talk obsessively about stagflation, economic sanctions — and wartime survival skills.

State media is now rushing to quiet online speculation of a possible imminent conflict with Taiwan, but they are simply not powerful enough to alter the bearish tone in the marketplace.

And on top of all these shocks, there’s China’s deteriorating demographic situation. The country’s population either declined last year or will decline next year, depending on which reports you believe. The total fertility rate is now at 1.3, which is lower than Japan, despite the end of the one-child policy. The working-age population has been declining for almost a decade now, and the country is aging so rapidly that its median age has surpassed that of the U.S. Even if the government pulls out some draconian policy to force Chinese people to have more kids (which will bankrupt their household finances and stir unrest), decades of workforce declines are already baked into the demographic cake. A smaller, older population will decrease dynamism, increase the economic burden on working-age people, and chill investment.

Rapid aging, of course, comes on top of the natural forces of technological catch-up and capital saturation. China has copied, bought or stolen a lot of technology, but now that it’s basically at the frontier in manufacturing industries, this will no longer be a big source of growth. And China has built so many buildings, roads, vehicles, and machines that simply forcing the creation of more cheap capital won’t lead to nearly as much growth as it did in the past.

In other words, China is perfectly in place for its second big growth slowdown, right at the place that Eichengreen, Park and Shin predict. And if growth is at 5% now, another slowdown of typical size might put it around 3% going forward — around the level of a developed country. We might see another few years where growth spikes back up to 5% — as it did in the Japanese “bubble years” of the late 80s — but historical precedent suggests that’s unlikely to be sustained.

So there’s a good chance we’re looking at the end of China’s economic miracle, even though it might take another decade for the world to agree that this was the end.

How good is China’s system really?

If China does indeed slow to near-developed-country levels of growth after these disruptions, how far will it have caught up? When Japan stopped catching up, it was around 75% of U.S. income levels. But if China stops catching up now, it’ll be at only around 30% of U.S. levels. If it slowly climbs up to 40% thereafter, it’ll still just be an upper-middle-income country. People will then say — with good reason — that the country hit the dreaded “middle income trap”.

Economists generally think that the level at which a developing company stops catching up reflects the quality of its institutions or technology. If building more buildings and machines and roads can only get you to 40% of U.S. GDP, the thinking goes, there must be some systematic weakness holding the country down. Personally, I’ve always felt that explanation to be a little tautological — simply taking the part of national income that we can’t easily explain and labeling it “technology” or “institutions”. It’s more a reflection of our ignorance than anything else.

But in China’s case, if the economic miracle ends here, it’s pretty clear what story people will tell to explain it. China simply turned away from the path of market reform, folks will write. Xi Jinping (and to a much lesser degree, Hu Jintao) thought they could turn back from the liberalizing path of Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin, but — surprise! — free markets and secure private property rights work best after all. The breathless articles suggesting that maybe Xi really has discovered how to make state capitalism work will be memory-holed, libertarian nostrums will return, and the “China can do no wrong” narrative of the past few years will be replaced with the equally simplistic “China can do no right”. A brief resurgence of 5% growth will reverse the triumphalist narratives for a few years, only to see them shelved again when it fizzles.

That, unfortunately, is how punditry and collective memory work. But in this case there will probably a core of truth to the post-slowdown narrative. China’s state-directed financial system really did prioritize lending to unproductive SOEs and (especially) to the real estate sector. Centralized authority and the pervasive dominance of the Communist Party made it possible — perhaps even inevitable — for a leader like Xi Jinping to begin personally mucking about in the gears of industry. A weak financial system and the dominance of SOEs really did force people to put all their wealth in their houses, which in turn helped push the less-productive property sector to nearly 30% of GDP. Reliance on stealing foreign technology probably helped supercharge Chinese catch-up for a decade or two, but the difficulty in switching to a regime of intellectual property protection might mean that this freewheeling approach to technology is now a liability.

And so on. Again and again, we’ve seen national institutions that are very useful for rapid development or postwar rebuilding turn into liabilities when a country gets richer. Usually this is in the form of an overgrown development state that just doesn’t know when to downsize itself and hand things over to the private sector, combined with a private sector that doesn’t know how to make decisions on its own when the state finally does retreat. All the major catch-up countries — Germany, Japan, South Korea — have had to deal with this. China is just having to deal with it a lot more.

And of course, China is also yet another object lesson in the timeless drawback of authoritarianism — eventually you wind up with a Bad King, and no way to get rid of him. This problem plagued Chinese dynasties just as much as their counterparts in France, Turkey, England, Iran, and everywhere else. For a while it looked like China might have finally cracked the code — invented a bureaucratic one-party oligarchy that could ensure smooth transitions of power, maintain checks and balances, and prevent the emergence of destabilizing personalistic rulers, even as it leveraged the traditional authoritarian strengths of concentrated investment and swift decisive policymaking.

Or not.

One reason China hit the slowdown at an earlier stage surely is due to its sheer size. Japan was 100 million or so. SK, Taiwan, fractions of that. All relied on exports driven to grow fast.

But you need a large external market for that, and the larger the ROW is relative to you the longer you can extend that period. That's probably why Singapore can do it indefinitely, and China hits a wall at circa 35% of US GDP. Because ROW relative to China is much smaller, compared to Taiwan, Japan, SK.

Japan's growth plummeted after its crash, but Korea kept growing fast even after 1998.

Should we expect China in 20 years to have income up just 50% like post-89 Japan, or up 250% like post-98 Korea?

One billion people with average income of $21,000 is very different from one billion people with average income of $42,000.