Interview: Saikat Chakrabarti, creator of the Green New Deal

He also discovered AOC, served as her chief of staff, and co-founded the Justice Democrats

Saikat Chakrabarti is not your typical political activist, to say the least. A former finance guy and startup founder and an early engineer at Stripe, Chakrabarti left industry to work for Bernie Sanders in 2015. From there he went on to found the Brand New Congress political action committee, with the goal of discovering new political talent. One of the people he discovered was none other than Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

Chakrabarti was just getting started. He co-founded the incredibly influential Justice Democrats and the think tank New Consensus. He became AOC’s chief of staff, during which time he wrote the original Green New Deal. It was during this time that Chakrabarti and I had a…vigorous debate over the economic policies that were included in that early incarnation of the climate plan.

But when I met Saikat in person, I found out that he and I disagreed on far less than I had expected. In fact, he’s one of the major proponents of industrial policy, which is a big shift I’ve been hoping to promote for years. He has a remarkably broad, detailed, and ideologically flexible vision of American progress. In this very long unedited interview, Chakrabarti describes how the Green New Deal came to be, how he discovered AOC, and what he envisions for the future of industrial policy, American politics, and the progressive movement.

N.S.: So, you co-wrote Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez' original Green New Deal. What do you think the biggest impact of that so far has been? How happy are you with the climate policy that Biden has come out with? How optimistic are you about the chances of getting a big climate package passed?

S.C.: When we started working on the Green New Deal, the world of climate politics was pretty different. In the activist world, there were (and still are) a lot of different movements like the "keep it in the ground" activists who focused on stopping new fossil fuel projects or the environmental justice activists focused on reducing pollution in their communities. Many environmentalists (and, as we've found out, fossil fuel companies) preached a kind of “climate austerity” in which reducing consumption, recycling just right and smaller carbon footprints would get us to ending climate change. In policy and academic circles, the majority of effort went into figuring out carbon tax/carbon pricing schemes that would set up the right incentives for the market to solve climate change.

There was a lot of good work being done in these circles (except by the people preaching climate austerity). However, we felt that almost everyone working on climate policy was approaching ending climate change as a necessary thing to do at the expense of our economy, making the political discourse all about "climate vs. jobs." On top of this, no one was talking about solutions even close to the scale of what would actually need to happen to reverse climate change. In fact, if you look at Bernie Sanders' climate change plan in 2016, it called for an 80% cut in US emissions by 2050 done largely through carbon taxes. This was considered very ambitious in 2016!

So we had two major goals when we were writing the Green New Deal, which was at the end of 2018/beginning of 2019 (the same time that the Democratic presidential primary races for 2020 were getting serious):

1) Create a plan that Democratic presidential candidates would have to respond to, creating pressure on them to have a race to the top against each other on climate proposals. We aimed to have an order of magnitude increase in the ambition of climate proposals being put out by presidential candidates and, through that, dramatically change the scale of what would be “politically acceptable.”

2) Introduce (but really reintroduce) a new approach to solving climate change that didn’t pit jobs against climate, but made the project of solving climate change the same as growing, upgrading and developing our economy, creating millions of high wage jobs in the process.

To expand for a bit on point 2, the team that worked on the Green New Deal was greatly inspired by the American approach to World War 2. In 1940, as the threat of war loomed, FDR famously delivered his Arsenal of Democracy speech. What's a little less known is he followed up in a speech to Congress by setting specific production targets for what America needed to produce, which included 185,000 planes, 120,000 tanks, 55,000 anti-aircraft guns, and 18 million tons of merchant shipping. For context, in 1939, America had built 3,000 planes. A lot of experts at the time thought FDR was just doing political theatre and these numbers were completely unrealistic. But of course, America crushed these targets--we built 300,000 planes in five years.

So how'd we do it? That's a long story (and I highly recommend the amazing Destructive Creation if you are curious about it), but it involved mobilizing our economy to hit actual goals. It wasn't a story of socialism vs. capitalism, but rather a story of all of American society trying, together, to do something ambitious and not being tied to any ideology to do it. We invested not just in infrastructure, but in industry. We invented new materials, like synthetic rubber when we had a rubber shortage. We invested to create whole new industries from scratch. We invested in existing industries to help them build out supply chains and upgrade their existing assembly lines. When it made sense, the government set up state-owned enterprises, and when it didn't, we contracted the whole thing out. When companies didn't convert factories to making what we needed, the government built factories for them and rented them out. When CEOs did poorly, we replaced them--and when they did well, we made them heroes and sent them around the country to teach other companies how to produce better and faster. In short, we tried everything, and when something didn't work, we didn't dwell on it--we forged ahead and tried something new. The result of this was not just that we won the war, but that we built the industries and wealth that created the greatest middle class in the world for the next several decades.

Our mobilization in World War 2 solved two big problems at once--the rise of fascism and the Great Depression. We took inspiration from this example when writing the Green New Deal because we are again facing a big problem--climate change--at the same time that the middle class is declining and wages are stagnating. We wanted to mainstream the idea of mobilizing our economy to solve climate change, and we wanted people to realize that all the work we must do to solve this problem is exactly the way to rebuild our middle class, push wages up, build wealth for everyone, upgrade our economy, and massively improve everyone’s quality of life--just like we did with our mobilization for World War 2. People don't always realize that all the things we need to build to end climate change--pollution free cities, electric cars, houses that stay warm in the winter and cool in the summer--are just better, and the work necessary to build all those things creates a lot of advanced manufacturing jobs. And the idea of our government investing to build new industries and upgrade existing industries is not something we only started doing during World War 2, even though that’s a great example. It's an idea as old as economic development itself, and as American as Alexander Hamilton. In fact, it's downright un-American to face a challenge like climate change and surrender.

So all that is to say that the biggest impact the Green New Deal has had so far, in my opinion, has been in bringing this approach to economic development and problem solving back to America. I say this not just because mobilizing our economy by investing in industry, infrastructure, and production is the way to tackle climate change, but because this approach can help us tackle other problems too--like a pandemic. It could even change our approach to developing our economy more generally. We should move away from thinking of our country as “developed” and no longer needing the state to do anything to thinking of ourselves as a continually developing country in which we celebrate our government investing in productive industries to advance our economy.

One result of this mindset shift on climate policy has been that Biden did not pit climate change action against jobs in his campaign. Instead, he talked about building the clean energy economy of the future in America. He talked about solving climate change as the same thing as upgrading our economy and reindustrializing the rust belt. This ad about building electric cars in America was an amazing example of that. And in his address on the COVID relief bill, Biden even used the example of the arsenal of democracy in WW2 to show what his recovery plan will be like. But it's not just Biden--at the beginning of the COVID pandemic, even Trump talked about mobilizing our economy like we did in World War 2 to tackle this crisis. Of course, he didn't then actually do it!

The Green New Deal did also succeed in its first goal. Democratic Presidential candidates all rushed to release increasingly larger climate plans in response to the Green New Deal. This massively shifted the Overton window on climate change plans and put pressure on Biden to release a “moderate” plan in that environment. The resulting $2 trillion plan he released was, indeed, moderate for the 2020 Democratic presidential primary. But it was bigger by an order of magnitude than anything anyone had ever proposed in the past. While I'm proud of the role we played in making that happen, plans are still only just plans!

And speaking of plans, to answer your second question, Biden's climate plan is pretty good! It's not big enough to end climate change. And even though he talked a lot about investing in American industry, there isn't much in there beyond some government procurement contracts (and, in case anyone in the Biden admin reads this Substack, I'd love for you to take a look at some ofthe proposals we've put out for investing in productive industry in America!). But that's fine, because if he manages to not just pass, but execute successfully in the next 2 years, people will feel the effects of new jobs in their communities. This will get the political capital needed to keep going bigger I really hope that at the end of the next 2 years, I can say that the biggest impact of the Green New Deal was that it pressured Biden into creating a $2 trillion climate plan that he then executed successfully, giving millions of Americans high-wage jobs and proving to the American people that the American government can still do big things.

And to answer your third question, I am fairly optimistic of a big climate package getting passed, but I don't think it will be a “climate package.” My guess is Biden’s COVID-19 recovery plan will include almost all of his initial $2 trillion climate change plan because Biden has, correctly, taken the position that we should tackle climate change by investing in the economy to “Build Back Better.” The Democrats have one more shot at getting a big plan passed through budget reconciliation this year, and I think they will use it for Biden’s recovery plan.

Biden has also already signed a bunch of executive orders which sound promising, like ordering agencies to procure domestic ZEVs and establishing a Civilian Climate Corps. But, unfortunately, passing big legislation and signing executive orders is going to be the easiest part of all of this. I am somewhat less optimistic Biden will successfully execute these plans just because execution is hard and there will probably be significantly less pressure on Biden to execute well once a bill gets signed into law. I hope I'm wrong, though, and there is a lot we can do to help Biden succeed.

N.S.: So it sounds like to a large extent, the Green New Deal was about changing attitudes and approaches within the environmental movement. You seem to want to steer environmentalists away from the idea of degrowth, away from thinking of climate change as a lifestyle issue, and away from market-based tools like carbon taxes. Is that right? To what extent do you think that has succeeded? Has the environmental movement learned how to embrace green growth and industrial policy?

And speaking of industrial policy, tell me more about your ideas in that realm. I know we're fans of many of the same books about industrial policies in America's past and in other countries. But what should an industrial policy look like now, in the America of the 2020s?

S.C.: On the first question: sort of. We do want to steer people away from the idea of degrowth and climate change as a lifestyle issue, but we aren't against market-based tools like carbon taxes. These solutions are just nowhere close to being enough to reverse climate change on their own, and they often don’t make sense to use as a first step. But in DC, they were sucking up nearly 100% of the oxygen on climate change proposals because they were very convenient for solving the political problem of DC bipartisanship.

And the goal was less to convince environmentalists and more to convince Democrats running for President and the broader American people. We were pretty successful there--almost every Democrat running for President endorsed the Green New Deal, the ones with major climate plans all talked about ending climate change as an investment and jobs program, and despite a pretty extensive campaign to scare people away from the Green New Deal in right-wing media, the Green New Deal (and, more importantly, the ideas in the Green New Deal) are broadly popular.

Democrats running for president also embraced the environmental justice parts of the Green New Deal--something I did not get into much in the first question, but which was a big part of what we were trying to advance with the Green New Deal. Environmental justice basically says that we should, when possible, prioritize creating new industries and jobs in places that have been hit hardest by the past several decades of deindustrialization, pollution, and other bad policy decisions. So that means, for example, invest in places like West Virginia and Flint, MI, first if possible. This is one of the ways the Green New Deal aimed to create broad-based wealth rather than just have new wealth go to the places that already have it. And on that front, I'm excited that Biden has already signed an executive order to make environmental justice a core part of his climate plans.

With environmentalists, our results have been more mixed. Newer groups, like Sunrise Movement, have embraced the idea of solving climate change through investment and development. Check out this ad they made for Mike Siegel . And while Siegel ended up losing to incumbent McCaul in that district by about 4 points, McCaul had previously won that district by 20-30 points in 2012, 2014, and 2016. But we certainly haven't convinced every environmentalist.

On industrial policy ideas, a focus of ours at New Consensus has been to create institutions that focus on investing productively with patient capital and institutions that do some level of economic development planning--some of the basic building blocks needed to do any industrial policy. Most developed countries have institutions like these, and they don't all look the same. For example, in Germany, a collection of non-profit banks known as the Sparkassen fund small and medium sized businesses (the Mittelstand), which do much of the high-wage, advanced manufacturing that Germany is known for. In Japan, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI, which has since become METI) made the industrial plans that helped Japan climb from economic disaster after World War 2 to becoming a wealthy, modern industrial powerhouse.

America has also had these institutions in the past. One of the three core pillars of Alexander Hamilton's American School of economic thought was to have a national bank focused on productive investment instead of speculation. The First Bank of the United States, the central bank Hamilton helped establish, focused on providing that kind of financing for development. And its modern day version, the Federal Reserve System, was originally established to perform more of an economic development function than it does today. Even today, we still have one state-owned bank focused on long term economic development left in America--the Bank of North Dakota. And it’s not a coincidence that North Dakota was the state that perhaps weathered the 08-09 recession best, ending up with a large surplus in 2009.

One idea we've advanced at New Consensus is to turn the Federal Financing Bank (FFB)--the bank housed within the Treasury that acts as the bank for federal agencies--into a fully fledged national investment bank and pair it with a newly formed National Reconstruction and Development Council (NRDC). The NRDC would be tasked with developing a regularly-updated, comprehensive National Development Strategy (NDS) comparable to the defense agencies’ annually updated National Defense Strategy Statements. The FFB would be empowered not just to do lending, but to also issue new classes of securities, organize private investors into projects, take equity stakes, and more. As an example of how this could be used to solve a specific problem, imagine that at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the NRDC had decided that it would be strategically important to build enough mask capacity to give every American a fresh supply of N95 masks every week, the way Taiwan has done. The FFB could have created a “PPE fund” that it contributed capital to and invited private investors to invest in as well. It could have then used this fund to guarantee purchases from 3M, giving them the confidence to ramp up manufacturing. It could separately set up contracts and provide financing to existing manufacturers to convert their existing assembly lines into N95 manufacturing lines. Maybe it would even contract the Army Corps of Engineers to replicate 3M's mask factories and lease them out for cheap to companies willing to build N95 masks for us--similar to the GOCO model we used in World War 2.

This model--a strategic planning organization combined with a financing arm--is inspired directly by the War Production Board and Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which led our successful economic mobilization in World War 2. And the FFB part of this proposal is a lot like an institution the US already has--the US International Development Finance Corporation--but that is only for developing other countries, not our own.

Another idea we've advanced has been to return the Federal Reserve System back to its roots as a network of regional development banks. So while the FFB/NRDC focuses on national-level development strategies, a network of regional development banks can bring in the kind of bottom-up input necessary to have successful national development. To do this, the Fed would expand its direct-to-business lending to support productive small and medium sized businesses--similar to the Sparkassen in Germany. And unlike today, where the NY Fed makes the biggest financial decisions, the Fed would empower its regional banks to develop their respective regions. The Fed could be informed by the NDS put out by the NRDC every year to guide its investing decisions while also feeding information about what's actually working on the ground back to the NRDC. This would be a great way to rebuild, with some intentionality, the small and medium businesses that are dying by the millions right now due to the COVID-19 recession.

But beyond policy, successful national economic development will take a different kind of political leadership than what we're used to. We need leaders who are willing to take risks, be creative, throw out ideas when they aren't working and double down when they are, think outside the box to call the nation to action, and always be pushing to go bigger and faster. Just as an example, a few weeks ago some of us at New Consensus began digging a bit more into our vaccine production bottlenecks. New Consensus put out an op-ed arguing for going faster since if we can shave off even a couple months in vaccinating all of America, we could save hundreds of thousands of lives. Worst case, we would end up with the capacity to vaccinate the rest of the world faster, which we will need to do if we don't want COVID-19 to become a yearly disease like the flu. But when we started looking into what the actual bottlenecks are in mRNA vaccine development, we mostly came across articles arguing for why we can'tdo it. These articles are interesting and I'd encourage the reader to read them, but the argument boiled down to our inability to make more of these nanoassembly machines and train enough people to operate them. This sounded surprising to us--if only a handful of these machines are making our supply right now, how could we not possibly make more of them? My colleague Zack Exley and I called a few people in industry who work on vaccine manufacturing to see if maybe we were missing something--perhaps these machines were incredibly hard to make? But the people we called, including someone at a company that makes these nanoassembly machines, thought we could easily build more in a matter of weeks. So why isn't Biden pushing to invest in building more of these machines now to ramp up our production?

The point of this anecdote isn't to say that there is one weird trick to upping vaccine production by building more nanoassembly machines. Even if these machines are the only bottleneck now (which I'm skeptical of), as soon as we fix it there will be a new bottleneck. My point is we need the kind of political leadership that tries to relentlessly figure out what we should be doing to go faster and does it. With vaccines, the only reason to not make more doses faster would be if there is some raw material we have to get from nature that we are running out of. But then our leaders should ask, why not make a synthetic version of it? We need leaders who assume there is a way to do better instead of assuming we're doing the best we can.

This is, unfortunately, the opposite of how most of our political leaders act today. From my time in Congress, I learned that politicians in America are greatly incentivized to do as little as possible as long as it doesn't get them in trouble. The consequence for action and failure is obvious to them--you get attacked in political attack ads and probably the media. Also your colleagues won't like you because you are the annoying person asking uncomfortable questions and telling people they could be doing a better job. But we need politicians to realize that often, the consequences for trying and failing are minimal compared to the consequences for not trying at all. We need leaders who are brave enough to question, break through barriers, and drive progresseven when there isn't public pressure to do so. Without that, I fear even the best designed institutions and industrial policy will not get us very far.

N.S.: I like your ideas for industrial policy. I've been calling for things like that for a long time myself, though my proposals weren't as specific.

On environmental investment, what do you see as the most important areas that need government investment? With solar and batteries so cheap now, it seems like the private sector is racing to install low-carbon electricity and transportation on its own. So where can the government make the greatest impact with its dollars?

Also, you're pretty optimistic about the Sunrise Movement embracing industrialism. But haven't they also been pretty strongly against upzoning and pro-density policies when it comes to urbanism? I feel like they might still have a strong strain of the degrowth idea in their ideology. Do you think that's true, and if so, can they be nudged further in a pro-growth direction?

Third question: What do you see as the biggest pitfalls for industrial policy in the U.S.? As in, how can we best make sure we emulate the successes of other countries and not the equally numerous failures?

S.C.: Thanks, I like a lot of the ideas you promote too!

But to push back a bit, I still think the government should invest in electricity/transportation. Maybe private capital alone gets us to a fully electrified grid and zero-emission transportation in 15-20 years, but government investment in, e.g., building production capacity, building supportive infrastructure, car buyback programs, and cheap financing for consumers could shave at least 5 years off that. There's no downside to going faster. Plus, we should build the capacity to get the rest of the world on zero emission vehicles and electricity too, since we only account for 15% of emissions worldwide but are one of the only countries rich enough to help upgrade the rest of the world. It will be interesting to see what China does in the next 10 years on electrification and transport. Currently, China subsidizes about 30% of its EV market. I'd bet they don't divest much, and instead focus on expanding faster and becoming the global leader in exporting electric vehicles.

Beyond vehicles and power generation/storage, the government should be investing in electrifying everything else. This largely means electrifying buildings and industry. We already have the technology to do this for buildings, and mostly for industry, but need to scale up massively and quickly. I'm a big fan of the work Rewiring America has done on this topic (and check out this super cool Sankey diagram they made to show what, exactly, is the source of emissions in America). There are also some last mile problems that account for a small but non-negligible amount of emissions like air travel and shipping. The solutions for these are still mostly in the R&D phase, and the government should invest in any promising solution to those problems now so that we can scale those solutions up in the next 10-20 years!

In parallel, the government should be investing in zero or negative carbon agriculture solutions, like regenerative agriculture and carbon farming, lab-grown meats, vertical farming, and kelp farming. Solutions in this space are in somewhat earlier stages than those for electrifying everything, so government investment would likely be a combination of R&D and trying to scale up the solutions that seem to be working.

If we do all of that, which covers building emissions, industry emissions, transportation, power generation, and agriculture, we've covered it all. And the really cool part of these investments is they build things we can export or even give to countries that will have a harder time than us reducing emissions. We can literally export carbon reduction by exporting clean steel, induction cooking appliances, heat pump water heaters, carbon-sequestering concrete, carbon-negative produce, etc. I'm a big proponent of the US doing a Climate Marshall Plan for the rest of the world to speed up the global race to end climate change.

Beyond industrial investments, our government needs to play a big role in infrastructure investments like building a ubiquitous charging network, desalination plants to address the climate change-fueled water crisis, zero-waste solutions, restoring damaged ecosystems (which can act as carbon sinks), upgrading cities to be more resilient against climate change by, e.g., building seawalls, building mass carbon removal solutions, and upgrading transmission lines like China is doing. But everyone mostly agrees that the government should be investing in infrastructure, so I won't harp as much on that.

On your question about Sunrise Movement--I'm mostly familiar with their national organization, and I can say with confidence that they definitely believe in solving climate change through investment and growth. I suspect what you've heard about them being against pro-density policies may be coming from some of their local chapters. Some of this may be coming from degrowth environmentalists who have joined those chapters, which are open to anyone. But in my experience, degrowth sentiment in progressive local groups often comes from a place of assuming leaders are going to screw over marginalized communities in the name of progress, like New York did when building Barclay's Center. Missteps like that are horrible because they create a generation of mistrust and default opposition to new projects. I faced a lot of this when working on the Green New Deal from everyone ranging from environmental justice activists to labor unions. People in America are used to progress meaning the rich get richer and everyone else gets screwed. Of course it doesn't have to be that way, but I can absolutely understand why people don’t give our leaders the benefit of the doubt.

On the third question, I see three major kinds of failures that industrial policy has had in other countries and in our own history. One is countries betting on the wrong horse, which takes the form of investing for too long on the wrong industry. Japan famously bet early on hydrogen fuel for cars, and that may possibly have been the wrong bet (though I believe hydrogen will be part of the final mix of ZEVs) as they are finally introducing electric cars late to the game. I am less worried about this for America. We have a diverse enough industrial base, a large enough labor market, and enough capital to bet on everything. If you look at the “feasible opportunities” visualization in Ricardo Hausmann's Atlas of Economic Complexity, and select America, you quickly realize that we could choose to build everything if we wanted to. Our currently unique financial position in the world means we can afford to take a VC-like mindset to industrial policy--we should not worry so much about losing money as long as we make sure to invest in the winners.

The second failure is failing to invest for long enough (or even at all) in industries that end up being successful. I am much more worried about this for America. Having no industrial policy is itself a policy, and that has largely been America’s policy for several decades. We are a large country that sees ourselves as developed and successful, and it's easy in that situation to get complacent, risk-averse, and assume we will always be on top. My fear of this failure is largely why I've dedicated the past several years of my life to getting a new kind of politics and economic consensus established in America.

The third major kind of failure is industrial policy that creates pain instead of gains for the vast majority of people. Industrial policy, if done properly, should make the vast majority of Americans wealthier and have drastically better lives. But if we don't plan for disruptions to existing industries, or implement half measures that just lead to funding companies to outsource more jobs, or create price hikes by implementing bad tariffs, we could cause all the new wealth we create to flow to the people who already have it and make most people's lives even worse. This is bad for the obvious reason that it causes unnecessary pain. But it is also bad because if our industrial policy doesn’t make people’s lives better, we will lose all public support for doing future industrial policy. Not planning for the social impacts of our industrial policy is a good way to ensure massive backlash towards it. I'm somewhat worried about the US doing a bad job here because we have not always been good at thinking through what will happen to people, especially people who don't have a lot of political influence, when implementing big economic policies. But the increasing power of people like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ro Khanna, Jamaal Bowman, and Cori Bush in Congress is a formidable check against that. And our response to this recession vs. the 2008 recession gives me hope that we are learning, as a country, to do better.

N.S.: Just to be clear, I think the falling cost of solar and batteries is a reason for government to invest MORE in those things right now, not LESS. I explain that in this Bloomberg post and this Substack post. The low cost means these things will pay themselves back even without the environmental benefit. But yes, I like all the other investment suggestions you have.

S.C.: Oh, good, then we agree!

N.S.: Anyway, let's switch gears and talk about politics. You talk about the new generation of politicians like AOC. You were sort of the person who first "discovered" her, right? Talk about a successful investment! Tell me a bit about how that happened.

S.C.: Well, I was part of a team, and I wouldn't say we “discovered” her so much as she was crazy enough to join a harebrained scheme that we hatched! The backstory (much of which is chronicled in Knock Down the House) is that in the summer of 2016, after working on the Bernie Sanders campaign, a few of us from that campaign--Alexandra Rojas, Corbin Trent, Zack Exley, and myself--started an organization called Brand New Congress. We wanted to recruit 400+ people to run for Congress, regardless of party, in a unified national campaign with a bold plan to rebuild America's economy. We were hoping to replicate the kind of movement the Bernie campaign had inspired, but focus that energy on Congress. Here I am talking about it when we launched.

The core of this idea was the belief that we needed a team of motivated leaders who were not the usual careerists to run for office. Instead of individuals all running with own agendas, we believed a team of nurses, doctors, teachers, principals, CEOs, factory workers, service workers, small business owners and others from all parts of the economy running on a big plan of action could make a compelling case for Americans to believe that, if they vote for this team, something could actually change. We were looking for people who a) actually knew how to do things, b) were real leaders who others in their communities looked to for support, and c) had a track record of being selfless.

At the time, the plan everyone would be running on was a lot of the Bernie platform, but with the addition of the kinds of industrial policy ideas we talked about in earlier answers. We focused on mobilizing the economy to, for example, build the healthcare system needed for universal healthcare, rebuild deindustrialized towns, reverse climate change, and in the process create broad-based wealth and end poverty. Over the next two years, we further fleshed this plan out. Zack did a fellowship at Harvard where he spent his time researching and talking with economists to further create a more detailed version of the plan. The candidates we recruited gave their input and perspective to develop it further. Zack and I did a trip to Europe to socialize the plan with some economists there because economists in Europe at the time were talking about these kinds of ideas more than academics in America. The final Green New Deal was basically a summary of this plan.

We recruited candidates by asking people to nominate leaders they knew on our website. We didn't allow self-nominations in the hopes that it would help filter out some of the egomaniacs. We separately had a team of volunteers scouring the web and local news to try to find these local leaders. Once someone got nominated, they got put through a multi-round vetting process, which involved multiple calls and video chats. Most of these people had no idea they were nominated, so they would usually get a cold call from me or someone else on the team trying to pitch them on this whole idea. It was a two-way interview--on the one hand, we'd be trying to figure out if this person would be a great fit on the team, and on the other hand, we were trying to convince them that we weren't totally out of our minds. Alexandria got one of these cold calls in December of 2016 after her brother had nominated her on the Brand New Congress website.

Fast forward to spring of 2017, and out of our goal of recruiting 400 candidates, we had recruited 0. We had a few dozen candidates we were excited about, but had not managed to convince a single one to actually run. Most people already doing great work in their community were repelled by the idea of going to Congress, and our idea of making it less abhorrent by having them go in as a team still seemed too far-fetched. This was when we had an idea: all these candidates we're recruiting are amazingly inspirational, so what if we had them meet each other instead of just talking to boring old us? So we planned a small candidate retreat in Frankfort, KY, in March, 2017, and invited the candidates we were most excited about to it. It was pure magic. Alexandria was there along with Cori Bush (who won her race this year) and Demond Drummer (who is now Executive Director of New Consensus). Here's a photo of it where I'm making an unnecessarily stupid face:

At that point I had talked to Alexandria a few times on video calls and Zack and I had met her once for dinner. We could tell she was seriously considering running, but she was unsure about taking on the third most powerful Democrat in the House. That retreat gave her the confidence she needed as she saw all these amazing people willing to take the leap with her. A little while after that, she agreed to run, and we launched her campaign.

Fast forward to fall of 2017. We had recruited all of 15 candidates, and were starting to run out of money. After the success of the retreat in Kentucky, we tried to scale up by doing a retreat every weekend, but this only got us so far and was exhausting as hell. A lot of the great people we found and tried to recruit to run still looked at us like we were crazy. We thought we could convince these amazing leaders to run and inspire America by kickstarting an exciting, national movement. But to kickstart this movement, we needed the leaders. It was a chicken-and-egg problem.

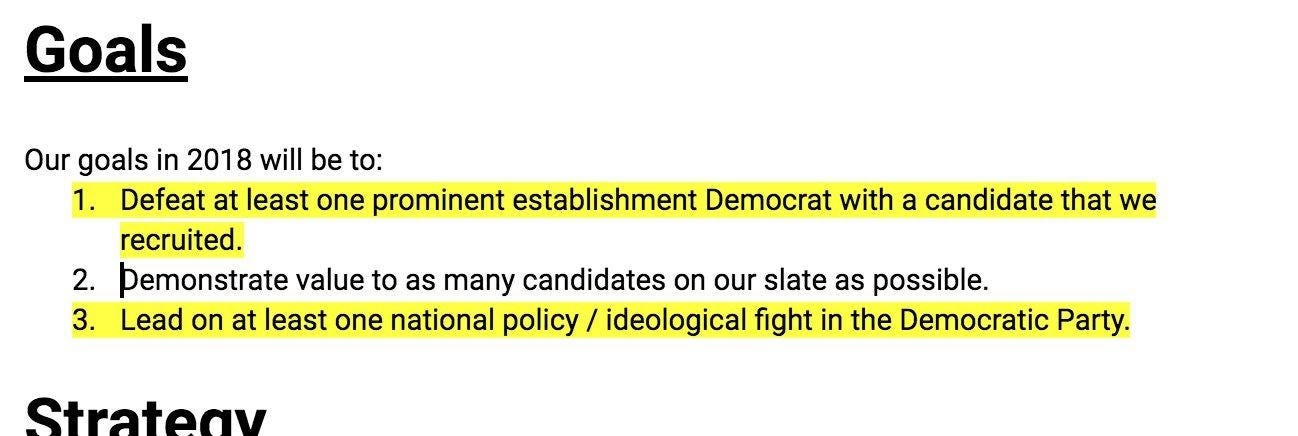

After Trump had won his election, though, a lot of amazing people had started running on their own in 2017 (including many we had talked to in the summer of 2016 but who had refused to run back then), so we began supporting some of these candidates with money, volunteers and tech. We had wanted to build a team from the ground up, so this wasn’t exactly part of our plan, but we tried our best to pitch them on this team idea anyway (with mixed results). Including them, we had about 70 candidates. But every candidate was outraised heavily and most barely had campaign infrastructure--especially the candidates we had recruited and convinced and whom we, therefore, felt a special obligation to. The result was that everyone looked like they would probably lose unless we made some big decisions. We started by writing down some goals for what we thought we could realistically do with what we had at the end of 2017. Here’s a screenshot of that doc:

To hit these goals, we needed to focus, so we made the decision to give up on doing a post-partisan project. At this point, we had only recruited one person to run in a Republican primary, and we were already losing faith in this part of the project after Trump got elected. In January of 2017, we had started a second project with the same team working out of Knoxville called Justice Democrats. We started this together with Cenk Uygur of the Young Turks and Kyle Kulinski of Secular Talk, and it had the same goals as Brand New Congress, but focused on recruiting people for Democratic primaries only. By fall of 2017, it was clear to me that Justice Democrats had more momentum. So I made the decision to hand off Brand New Congress to the people on the team who still believed in the Republican recruitment project (and Brand New Congress still exists!) while I, and the rest of the team, would just focus on Justice Democrats.

The second decision was to throw a hail mary and go all-in on Alexandria's race. There were a few reasons to focus on Alexandria's race. Tactically, Justice Democrats had its largest pool of volunteers in New York, the voter turnout in New York primaries was so low that we only needed to mobilize a few thousand votes to win, and the media being so concentrated in New York meant we could get national headlines more easily. We thought it might just be possible to overcome the 100-to-1 fundraising gap we had in that race if we focused all our efforts on it. Strategically, we believed that defeating the third most powerful Democrat in the House could be a huge shock to the system and create the kind of momentum needed to win a few more races. Alexandria was, of course, an incredible candidate, but that wasn't a big factor in this decision because so many of the other candidates we had recruited to run were also amazing!

From the beginning, we had regularly rotated leadership at Brand New Congress and Justice Democrats to let lots of people get experience. At the time, I was running Justice Democrats, so I handed off leadership to Nasim Thompson and moved back to New York to work full-time as co-campaign manager on Alexandria's campaign. Corbin Trent and Alexandra Rojas came with me to run her Communications and Field program while sleeping on the floor of my one bedroom apartment, which in some other cities would be a large closet. Over the next few months, Alexandra built an incredible Field operation together with local volunteers that contacted hundreds of thousands of voters while Corbin managed to wrangle some major national press hits and key endorsements at the exact right moments. Incredibly talented local supporters built new campaign tech that was actually game-changing, led a historic petition drive, and built a truly innovative social media campaign that went well beyond just Alexandria’s Twitter account. And of course, Alexandria worked like hell, personally writing and helping to direct her viral campaign video while also knocking it out of the park in her televised debate with Joe Crowley. All of this got us some momentum. We had hope.

Two weeks out from the race, we got a leak that the Crowley campaign had us up in a poll (we later learned this information was false). We got so excited that we did our own poll--at great expense relative to our budget. It showed us down 35 points. We were crushed. But Alexandria, the team and hundreds of volunteers powered on, and all our efforts ended up turning out people that the polls did not catch. It all added up, and we won. We were all shocked, especially Alexandria.

What was the bigger surprise to me was just how impactful her victory ended up being. We thought it'd be big--maybe as big as when Dave Brat defeated House Majority Leader Eric Cantor--but it totally eclipsed that. Like we hoped, it created the momentum needed to help 3 other Justice Democrats candidates win in 2018 (Ayanna Pressley, Rashida Tlaib, and Ilhan Omar). But unlike anything we could have imagined, Alexandria was able to use this newfound international spotlight to change the Democratic party.

This change didn’t just happen because she’s an incredible communicator. It happened because she was willing to seize the opportunity starting that very night, using her impromptu victory speech to rally supporters to the next Justice Democrats’ elections that were coming up. We knew the media would lose interest in a day if we didn’t engage. So even though she was beyond exhausted, Alexandria did dozens of national media hits relentlessly for the next week straight, barely sleeping, to define the media narrative instead of letting the media define her and this movement.

This change also happened because of her courage to do exactly what she said she would when she was running. She didn’t play it safe. She was herself. She never stopped talking about the issues in her district. And she seemed to be able to engage on issues in a whole new way that people connected with. The best example of that courage came when Sunrise asked her to support their sit-in in Nancy Pelosi’s office with a tweet. Their original demand was for Pelosi to do something about “green jobs.” But Alexandria decided she wouldn’t just tweet--she’d join the sit-in and turn this into a big, national moment. And instead of just “green jobs,” we worked with Sunrise to make a concrete demand for a Green New Deal. Of course, that’s a whole story in itself.

We thought we needed a team of at least 30 people to do anything in Congress because of how powerless individual members of Congress are. And while I still believe we need that team for real political power, Alexandria showed us just how powerful a single member of Congress can be if they stand for something and have the courage to fight for it.

N.S.: Wow, that's quite the epic story!

I notice that one of your 2018 goals included defeating an establishment candidate within the Democratic party and winning an ideological fight within the Democratic party. Was this just to get attention and establish yourselves? Or was it the beginning of a strategy of factional struggle within the party? As I see it, the intense factionalism of the Bernie movement -- the obsession with inside baseball, denouncing the Democratic establishment, making rivals "bend the knee", and so forth -- ended up leaving it out in the cold after Biden's victory, at least in terms of appointments and direct influence. Is it time to reevaluate the anti-establishment strategy? Is there a danger of Justice Dems turning into a sort of Tea Party of the Left, always fighting with the leadership and making it hard to get things done? Is the time for revolt over? Or is it still necessary to keep the mantle of outsiders leading a popular (dare I say, populist?) revolt against an ossified party establishment?

And that reminds me of another question: To what degree are New Consensus and Justice Dems actually a movement of the Left? The term "socialist" has been thrown around a lot, including by Sanders himself, but what does that mean in this day and age? And to what degree do the Justice Dems view themselves and their agenda as the heirs to the socialist movements of the past?

S.C.: Our original goal was to elect a big new team all at once that could go in and get stuff done. When the movement didn’t take off, we took stock and realized we could at least win one seat. I don’t think any of us were thinking in terms of starting a “factional struggle.” We honestly didn’t have any idea what one person--in this case Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez--might be able to do if they were elected. But we hoped that a high profile victory of someone like Alexandria defeating Joe Crowley, combined with us leading campaigns for certain policies, might start something that could change the landscape of the ideas that our politicians were considering. Rather than trying to bend anyone’s knee, we just wanted to show that a politics of big, bold ideas could gain followers and generate energy and power.

To back up slightly and give context to this whole project, we started Brand New Congress (BNC) and Justice Democrats (JD) because we believed our political leadership was failing on the job. On a policy level, we believed they were not presenting solutions that would actually solve the very real and very big problems facing our country. And politically, ideas that are incredibly popular in America--like getting rid of money in politics, increasing the minimum wage, or universal healthcare--were not getting the light of day in Congress.

There are a lot of reasons why politicians get so out-of-touch from real solutions and the real needs of people. Our political system incentivizes politicians to do as little as possible so as to minimize risk of failure, which I talked about earlier. And politicians themselves come from a very narrow segment of the population, which gives them myopic perspectives. A majority of Congressmembers are millionaires. The average age of a congressperson is about 60. Lawyers are heavily overrepresented as a profession.

And of course, there is the influence of money in politics. People often think of this as wanton corruption--big company gives politician money to vote for X. This certainly happens, but a more subtle and nefarious effect of our expensive elections is that the pressure to raise money means our politicians spend a lot more time talking to donors than anyone else. All that time talking to a narrow segment of wealthy people influences their worldview because our politicians are people. There are a million other ways money influences our politicians that I could probably spend a whole essay talking about, but the short of it is it’s strong and not always in the ways people think.

With Justice Democrats, we wanted to counter these pressures on politicians that kept real solutions from gaining traction in DC. We wanted to apply a larger, opposite pressure to get politicians to go for big ideas. The strategy, at least when I was involved in JD, was not to become a “Tea Party of the Left.” And even if that had been our goal, it’s important to remember that, unlike the Tea Party (which, at least originally, was ideologically just committed to cutting government and taxes), the ideas we were fighting for were popular. We weren’t fighting just to make a political point or have our “faction” win. We were fighting to achieve real outcomes for Americans by pushing the Democratic Party to fight for big solutions for the American people. Democrats managed to win power for decades in the mid-1900s with this strategy, and they could do it again.

I will say that there certainly were people in JD that disagreed with me and believed we should just focus on the factional fight within the party. But I still believe the big opportunity is not just to compete in deep blue districts to win power for a faction within the party, but to compete everywhere with big solutions. We need people who won’t campaign as “progressives” or “conservatives” or any current political tribe, but simply fight for the whole of America. I also believe we should keep the pressure on our political leaders to go big and execute their solutions. Pressuring politicians has gotten us this far, and there is a lot at stake if our leaders fail. I don’t see it as a question of, “Should we revolt?” America faces very real problems that we must solve if we wish to reverse our decline. When our leaders are solving them, we should cheer them on! And when they aren’t, we should pressure them, and democratically challenge their power. We’re lucky to live in a democracy! Let’s use it.

N.S.: And that reminds me of another question: To what degree are New Consensus and Justice Dems actually a movement of the Left? The term "socialist" has been thrown around a lot, including by Sanders himself, but what does that mean in this day and age? And to what degree do the Justice Dems view themselves and their agenda as the heirs to the socialist movements of the past?

S.C.: I don’t know if Justice Democrats today sees itself as a Left movement or not, but when we started BNC and JD, none of us thought about what we were doing as a new “movement of the Left." A lot of the ideas we championed, especially the industrial policy ideas, have since been taken up by the Left--and AOC and the Green New Deal had a lot to do with that--but those are not necessarily “Left” ideas. We wanted to find a new set of leaders that could win a big majority of the entire nation and fundamentally change the political landscape. And we wanted to do this explicitly as people from neither the Left nor the Right because we believed leaving the baggage of these labels behind would be necessary to win the kind of majority needed to implement big solutions. Plus, all of us, personally, hated being defined by narrow political labels when our ideas ranged far outside of their bounds.

In short, we wanted to create a whole new kind of movement, but we failed at that. In the process, what we worked on sort of defaulted into the Left. This was partly because the media needed a narrative to fit the left-right frame that all political reporting uses, and partly because a lot of our movement was still the remnants of the Bernie 2016 movement.

New Consensus is, as our name suggests, trying to put together a new economic consensus for how we can solve big problems and create a society where everyone thrives. We’re strategically somewhat inspired by FEE which was instrumental in the 40 year project to create a new right-wing economic consensus in the latter half of 20th century (if you want to learn more about that, I highly recommend Invisible Hands by Kim Phillips-Fein). The economic consensus we want to create is not based in socialism or capitalism or any ism, because we believe the isms are false constraints that we can’t afford to tie ourselves down with. Like FDR did in WW2, it’s more about trying everything, testing different ideas, and focusing on the actual results.

I’m not the best person to ask about what a socialist is today because, like you, I’m not entirely sure myself. I’m not a part of any socialist chapters or groups, and I have an aversion to labeling myself anything, so I certainly am no authority on modern day socialism and don’t want to misrepresent it. But I did spend a lot of time around Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) members through my work for Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, so I learned a few things. I learned that there are people in socialist circles today who, like socialists in the past, want the state to control all means of production. But that is a very small faction in the socialist movement, and those socialists are not the ones in power anywhere. For many others, including people like Bernie and Alexandria, socialism is about focusing on the needs of people and workers more than corporations and owners. In an interview with Colbert, Alexandria answered the question of what being a democratic socialist means to her with, “I believe that in a modern, moral and wealthy society, no person in America should be too poor to live.” I thought that was a pretty good summation of what many socialists believe today, and I agree with Alexandria that this should be a goal in America.

But one thing I’ve sometimes found frustrating about the resurgent socialist movement is that it does not focus on investing in a better means of production. Modern socialists tend to talk about distribution, but not production. Distribution is important, but people understand that wealth must be generated in the first place to be distributed. It’s hard to have an argument about how to distribute the profits from making cars in Janesville, WI, when GM is simply shutting down the factory and moving it to Mexico. And on this point, the right has, so far, done a better job in their message. I was amazed when I saw Donald Trump, who is very much not a socialist, tell his voters, “Our politicians took away from the people their means of making a living and supporting their families,” and followed that by saying he wants to rebuild it. And it’s Marco Rubio, of all people in Congress, who has one of the more extensive analyses I've seen on state-led investment and industrial policy.

N.S.: That's interesting. To me, your ideas sound less "socialist", whatever that means, and more like a sort of progressive industrialism in the vein of FDR. Do you think there's a real chance for a sort of industrialist movement to coalesce in this country? And if so, who will comprise it? Do you think AOC will be part of that movement?

Also, I wanted to ask you a little more about AOC. It's pretty amazing how she's progressed in such a short time. What do you think makes her such a generational political talent? What's her secret sauce?

S.C.: Well, not to be annoyingly anti-label, but what makes it progressive? The basic economic stuff we’re talking about has been put into action in American history and around the world by leaders of all different political stripes--including capitalist liberal democrats, social democrats, communists, and fascists. We’re just talking about investment. And of course, we want to do that the American way, under our liberal democracy, just like we’ve done it many times in the past. There were in fact many leaders of the Reagan revolution who thought they were coming to power to do this, but found themselves outmaneuvered by the Chicago School.

There is a very high likelihood that a new industrialist movement will happen in this country. Crises create moments where new movements with new ideas have a chance to rapidly win over a big majority of the country. This happened with the Great Depression and FDR. It also happened with the stagflation of the late 70s, which the right used to usher in the Reagan Revolution. The people who, in that moment, are able to clearly articulate why the current system isn’t working and why their new system will, can win. And unfortunately for us, we’re entering a decade of many crises. Climate change will cause more systemic infrastructure failures like we saw in Texas. Refugees fleeing uninhabitable areas will test our democracies (see how much backlash only about a million refugees in Europe created). As central banks do everything they can to hold economies together, we’ll see greater asset bubbles followed by greater crashes. In the midst of all this, we’ll get the usual answers from different camps. Some will say we gotta just keep the banks and economy afloat, and others will say we need to just get relief to people. And don’t get me wrong, both of those things are necessary to keep treading water. But it won’t work forever. In that moment, another camp could say, “Actually, we need to fix the underlying problems directly. We need to rebuild productive industries for the long term because that’s actually what powers our economy. We need to rebuild this failing infrastructure so it can withstand sub-zero freezes. We need to rebuild for the future.” And that could make a lot of sense to a lot of people who will have seen how the bandaid solutions are not actually solving our problems. But the bigger question to me is your second one--who will comprise this movement?

Among Republicans, there is already a kind of new industrialist movement taking shape, and it’s in the Donald Trump wing of the party. It’s more rhetorical than anything else because, as we saw, despite his promises, Donald Trump did not actually rebuild our means of making a living. They are currently united more by their culture wars than anything else. But it’s there, and people like Josh Hawley are its successors. If this is where the new movement comes from, it’s going to come along with all the other crap it’s associated with. And like with Trump, all this other crap will take center stage. The Republican industrialist movement is xenophobic, anti-democratic, and anti-immigrant. It is uninterested in solving any of our major social problems, like mass incarceration, our failing healthcare system, or our failing education system. Their worldview is oddly zero-sum, despite their industrialism, and in that world, they want to distribute this fixed pie of wealth to the wealthy. They believe we can’t have more immigrants because jobs are fixed (something I thought you rejected pretty well in this post). They believe we can’t have universal healthcare because they can’t imagine us increasing our supply of healthcare to give everyone quality healthcare.

So I do hope there is a more powerful “democratic industrialist” movement, and that is what I've been working on. This “democratic industrialism” must have some core, non-negotiable values. It should stand for democracy, first and foremost. It should believe in a fair, multi-racial society and strive to create better lives for all in America, regardless of race, gender, or anything else. It should believe in welcoming immigrants to come join us in this great American project--especially because there will be so much work to do. And it should believe in solving problems at a scale where the vast majority of Americans’ lives will be improved, rather than just the lives of a wealthy few. This last part means that our industrialism is combined with investing in social programs. We should use part of the wealth we create by upgrading our economy to build the best universal healthcare system in the world, the best public education system in the world, and end problems like poverty, hunger, and homelessness.

Democracy and inclusiveness are important not just on principle but also out of practicality: we live in a democracy, so if we want to see this happen, the people will need to support it. The way to win their support is to pitch them on a plan that benefits everyone.

The same way FDR was one of the few figures in the early 20th century to push back the international wave of fascism, which was the right-wing version of industrialism, we need a “democratic industrialist” movement to do the same today. The right-wing authoritarian wave today is also international. We see it with figures like Bolsanaro in Brazil, Modi in India, and Orbán in Hungary. And it’s not going to go away on its own with just a return to “normal.”

What we see over and over, though, is that the right-wing industrialists are all talk and no action when it comes to actually investing in industry. They win their votes with racism and xenophobia, because that’s easier than rebuilding an economy. Their “industrial policy” tends to just be corruption and giant handouts to the wealthy who don’t use it to build anything new. Trump felt he could get away with just building a wall, and only a few parts of it. He didn’t need to build those factories he promised during his campaign. The only way democratic industrialists can win majorities and keep them is by actually building a better life for people.

N.S.: Also, I wanted to ask you a little more about AOC. It's pretty amazing how she's progressed in such a short time. What do you think makes her such a generational political talent? What's her secret sauce?

Saikat: I agree with you--Alexandria is incredibly talented. But I do want to reiterate that there are tons of incredibly talented people out there. When we were doing BNC and JD, we came across dozens if not hundreds of people who were extremely talented. Not all of them were talented in the same ways that Alexandria is, but any one of them would run laps around the average Congressperson in DC. I’m not saying all this to take anything away from Alexandria, but more to give people some hope. There are hundreds if not thousands of people as talented as Alexandria out there, and instead of putting all our hopes and dreams on the shoulders of one person, we should encourage those talented leaders to run and join her.

But Alexandria’s “secret sauce” is that she tries. This is also hopeful because more people than you think could become incredible political talents simply by trying! I watched her campaign and she was constantly trying out different ideas and messages, learning from reactions, and working on improving herself. She would put herself out there, even when it terrified her, and learned from real world experience rather than spending a lot of time on “messaging strategy.” When she does committee hearings, she does multiple prep sessions, stays for the whole hearing (which is rare in Congress), and uses everything she’s hearing and all her prep to come up with the best questions to ask. Of course, it helps that she doesn’t spend a single minute dialing for dollars, so she has way more time than others in Congress. We’ve all heard about how master violinists or star athletes do thousands of hours of intentional practice. She brings that kind of intentional practice to things like figuring out how to best message a policy or how to best use a moment to change public opinion.

Through this, Alexandria has turned herself into a messaging genius. People often conflate this with thinking of her as a social media genius, but her real skill is that she knows how to take policies and complex ideas and distill them down to the parts that matter and that will connect with people. And of course, the same way FDR mastered the new communication technology of his day (radio), and Reagan mastered the new communication technology of his day (television), Alexandria has mastered social media, the new communication technology of her day. It’s necessary for politicians trying to bring about generational systemic change to master new technologies that let them talk directly to the people. There’s a tendency among established politicians to pooh-pooh this, but it’s to their own detriment.

There’s one other very important ingredient to Alexandria’s success--she has an actual goal that is not simply her political career. This comes through to people when she talks and acts. People can see, whether they agree with her or not, that she is fighting for others and for something she believes in. It gives her the freedom to make big, bold moves like the sit-in at Nancy Pelosi’s office demanding a Green New Deal. This, too, is hopeful--because the only people in this country who care about their political careers are people already in politics, and that is a tiny minority of people.

N.S.: Well, I hope both she and New Consensus can help jolt America out of the rut we've gotten ourselves into in the last couple of decades. I have high hopes! Don't let me down!

Which brings me to the final question: What's next on your plate? What's next on New Consensus' plate?

S.C.: Well, it will take a whole lot more people than just AOC and New Consensus to do it!

I'm working on a few projects right now. At New Consensus, we're working on some proposals for how Biden could pandemic proof the country now, while there might be political capital to do so. More broadly, we are trying to promote some of the ideas I’ve talked about in this interview with both people in Congress and with the broader public. We’re also creating short videos to explain things like the Green New Deal and basic economic topics. If you are excited by the kinds of ideas I talked about in this interview and want to help us expand them, please support us!

I’m also working on a podcast with Corbin Trent and Zack Exley, two of the co-founders of Brand New Congress and Justice Democrats. It’s called Building the Dream. Please subscribe wherever you listen to podcasts!

And finally, Corbin, Zack and I have also started a new political group called No Excuses that is focused on pressuring Democrats to live up to the promises they campaigned on with their majority. We started when Joe Manchin came out in opposition to relief checks, and we quickly put up radio ads in West Virginia to pressure him. He backed off his opposition a couple days after that. We believe that Democrats need to execute on their promises not just to help people, but to have a shot at keeping or even expanding their majority in 2022. The country will be demanding results, and excuses like the filibuster won't cut it if Democrats fail to deliver. If you agree with us and want to support this project, you can do that here!

And I just want to end by saying that, despite everything that's happened in the last year and all this talk of America being in a rut, I am an optimist. I believe in America. My dad came to this country in the 70s after being recruited at an American immigration office in Calcutta, India. Isn't that amazing? America was doing so much work back then that we were recruiting immigrants to come, inviting the world to join us in building this great nation together. My father came here with less than $20, leaving his entire family behind, like so many immigrants do. But he had faith that, despite the incredible risk, it would be worth it. America was where dreams came true. My father came from abject poverty in India, often going days without food. But in America, he got the chance to build a stable, middle-class life and lift our family in India up from poverty as well. I believe America can be a country that rises above its divisions to create a society where everyone is excited for the future--their own future, their children's future, and the future of the entire country. All we have to do is try.

One thing:

- Hell yeah for this guy and his ambitious optimism!

This is a fantastic interview. It further convinces me that the only way forward for the Democrats is to re-embrace the economic legacy of FDR.