Interview: James Medlock

The pseudonymous prophet bringing the word of Social Democracy to the masses

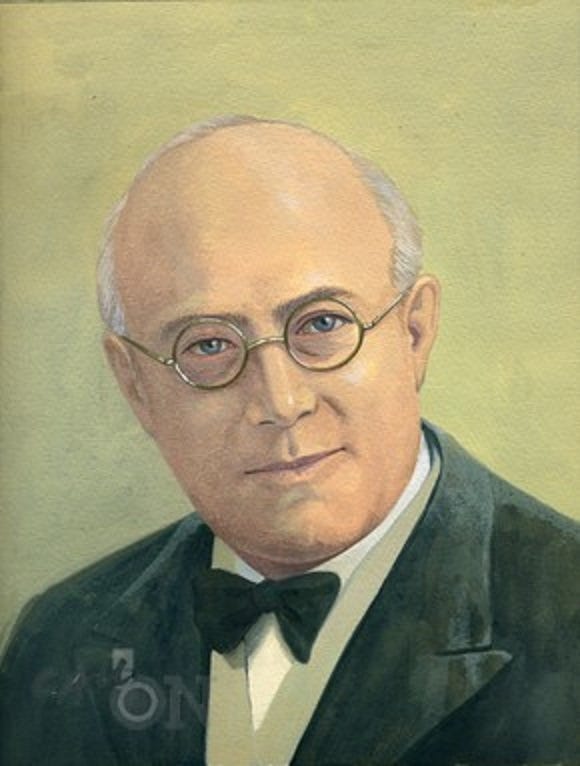

This is not a picture of James Medlock. It’s a picture of economic historian and sociologist Karl Polanyi. “James Medlock” is the pseudonym of a Twitter personality who has been stirring up the left-leaning portion of the internet. But instead of the usual Twitter routine — denunciations, anger, etc. — Medlock has thrilled people with his relentless calm and the power of his simple message. That message is that people simply need more money, and we know how to get it to them: Universal programs, higher taxes, and stronger unions. A self-proclaimed “social democrat in the streets, market socialist in the sheets”, Medlock has captured the attention of major Twitch streamers and gathered a Twitter following that spans all ages and walks of life. Often sporting sock emojis (for “socdem”, or “social democrat”), Medlock’s followers have become the Nice Guys of Left Twitter, subduing haughty libertarians and obstreperous tankies alike with a relentless barrage of cheerful humanitarianism sprinkled with empirical data. Their numbers have steadily grown, and AOC follows Medlock now too. In my opinion, he would make a perfect policy advisor.

In the unedited interview that follows, Medlock explains the pillars of his worldview, often referred to as Medlock Thought.

N.S.: So, as far as I can tell, our first Twitter interaction was in January 2019. Is that about when you started posting? What possessed you to become a pseudonymous Twitter celebrity? Did you have any idea you’d eventually become known as the leader of an online movement for social democracy?

J.M.: So initially I spent a lot of time arguing about politics on reddit, but I never really felt at home in the various politics subreddits. I jumped ship for twitter in 2019 because I felt like maybe I could find my place in the discourse a bit better on a platform without walled off communities. I didn't have any expectations of becoming anything more than a reply guy, I was mostly after catharsis and learning-through-arguing (one thing I discovered on reddit was nothing is a better motivator to read piles of papers than getting owned online). And then things kind of snowballed from there. I wouldn't want to overstate my influence now, I'm still relatively small in the scope of things, but I definitely found the community of like-minded people I was looking for beyond what I ever could have imagined.

N.S.: Would you describe your views as basically "Universal programs, higher taxes, stronger unions"? That's basically what I know you for.

And how have your views on economic issues evolved over time? Did you have any moment of enlightenment when you hit on this simple model? Or did it evolve gradually as you encountered ideas you liked?

J.M.: Yea, I think that's a good summation. I've always had an egalitarian political orientation and I studied sociology in college, but I hadn't really taken a deep dive into policy specifics until after 2016. Trump winning and Bernie being surprisingly competitive made me feel like what was possible politically was broadening, and I wanted to know what, exactly, the left should do if it took power at some point. I felt like a natural starting point was to look at where the left has been most successful at building functional egalitarian institutions and so I took particular interest in the Nordic countries. From there I found Matt Bruenig's old blogs, and sort of went down the rabbit hole of the mid 2010s blogosphere. (Insert dramatic montage of me spending all of 2017 staying up late, reading hundreds of blog posts, journal articles, blog post rebuttals, and white papers, furiously taking notes but crossing them out, and then, finally, with a look of triumph, writing a single line on a piece of paper: "taxes = good"). But in all seriousness, I wouldn't say there was an ah-ha moment, just a process of things coming slowly into focus. And I'm really glad to see Substack getting popular now because I've long said that short blog posts are the best medium, quick enough to not be a serious time commitment, but with enough links to follow if you want to go deeper.

N.S.: Nice. I hope the old Noahpinion was among the ones you read? :-)

OK, let's talk about "taxes = good". If I'm not mistaken, you're a big supporter of value-added taxes (VATs), like the ones used in Europe. I've seen you get in some ferocious battles with certain segments of the left who say VATs are regressive. What's that all about? Why are VATs good?

And a second question. One idea that has gained a certain amount of popularity -- or at least notoriety -- is MMT. MMT people believe taxes are not necessary for funding government spending, and that their main use is to equalize the wealth distribution. Basically, they think the only purpose of taxes is to bring the rich down, and we don't need them to lift the poor up. What do you think about that?

J.M.: Yea, I did go through the old Noahpinion archives, I still love referencing this post about how Japan in 2011 was a case study on how bringing more things into the cash nexus doesn’t necessarily increase freedom, in part because of transaction cost externalities.

I think VATs are a super useful tool, there's a reason why the US is one of the only countries in the world without one. They're low-salience, because the tax tends to be hidden in product prices and is paid in tiny increments over the year without any accounting of how much has been paid in (this is an important feature in an anti-tax country like the US). They're administratively efficient, as they have a self-enforcing mechanism that makes evasion pretty rare. And they're a "money machine," conservatives often worry that implementing one would be like throwing gasoline on the fire of our welfare state. The usual knock on VATs is that they're regressive, and in a vacuum this is true. But when considering regressivity, it's important to not just look at the distributional impact of the tax itself, but also the spending it enables. The net effect of a VAT-funded universal benefit is a big transfer to the poor, and away from the rich. Basically, the rich consume a lot more in absolute terms, and the value of a lump sum benefit is much higher to someone with low income. People often counter with: well why not do a progressive tax instead, it'll be even more progressive than the VAT+transfer? To which I say, yes, we should do that too. But we shouldn't get caught in a loop where we reject every tax because there's another tax more progressive than the last, because that would end up with a tax solely on the single richest person in the world (which happens to be only one person away from Grover Norquist's ideal tax system). Too much of the tax discourse is focused on *tax side progressivity* when we really should be focusing on *overall system progressivity*. The Nordics manage to have some of the most progressive tax and transfer systems in the world, not by narrowly focusing on either end, but by taxing everyone a ton (including, but not limited to, the rich) and giving everyone a ton of welfare and public goods. That's not to say there isn't an important role for steeply progressive taxes too. I think there's a good case to be made for top marginal rates on the right hand slope of the laffer curve, as a way of compressing the income distribution. And it's also worth taking into account the current context. In the US, where market inequality is sky high, we can manage with a more progressive tax system than other countries (at least so long as we remain this unequal), and we should make sure that any regressive taxes we implement are done alongside welfare state expansions that leave poorer people better off. We also have plenty of room to deficit spend while we’re recovering from the coronavirus, and we should take full advantage of that. But with all that said, I worry that in the long term, if the left rejects things like VATs out of hand, we'll be stuck doing kludgey ACA-like reforms that are designed minimize explicit taxes by relying on public-private partnerships, mandates, and means-testing, rather than clean, social democratic approaches along the lines of Medicare for All. We shouldn't prioritize low prices on consumer goods over the provision of plentiful public goods!

In terms of MMT, insofar as it's really about policy advocacy for accepting higher deficits, as you've argued, I think it could push things broadly in the right direction. Deficit fear mongering has done a lot of damage. But overall I don't think the rhetoric about taxes is useful. As I understand it, MMTers are mostly rephrasing what taxes are for (inflation control), not really whether or not we need them. I worry vulgar MMTism being pitched to the public would just encourage people to push for tax cuts rather than benefit increases (the Kelton article you link certainly makes the case that the rich should embrace MMT to avoid higher taxes on themselves). I'd like to see public spending increase by 10-15% of GDP. I buy JW Mason's case that we could do ~3% of GDP in deficit spending to fund big green investments without worrying about it, but for full social democracy I just don't think there's a way of getting around taxes. We need a big transfer of real resources from private consumption to public consumption. Is telling people "actually when we tax you, we're not using that money to fund popular spending, we're destroying that money, and we're funding spending out of nothing" really a good way to get people on board? I'm skeptical. We can push for more aggressive monetary and fiscal policy without playing word games, in fact I think it's easier to do that directly rather than getting caught up in battles about semantics.

N.S.: OK, let's talk about universal programs. In general it seems like there are three arguments for universality: A) it makes administration easier, B) it gets more political support for welfare spending because everyone realizes that the benefits don't just go to the people they don't like, and C) it avoids the high implicit income tax rates that can result from phase-outs at low levels of income for means-tested programs. Are there any other advantages?

Anyway, those all seem like strong advantages to me. But in the case of COVID relief, targeted programs seemed like the clear winner. Pandemic unemployment benefits -- sometimes called the "superdole" -- were hugely successful at reducing poverty, with no apparent work disincentive effects, at a fairly reasonable fiscal cost. Meanwhile, the near-universal $1200 checks in the CARES Act, though extremely expensive, mainly just seemed like they ended up convincing lots of people that $1200 was all that Americans were getting. And almost all other countries went with purely targeted relief programs, which were effective and popular. Was COVID simply a singular case in which targeting made more sense? Or did we learn something here?

And aren't there other targeted programs that make a lot of sense? Housing assistance for the homeless, for example, seems a lot more effective than just giving homeless people cash. Unemployment insurance seems like an effective way of fighting recessions. Social Security is only for the old, yet it has been a remarkably durable and successful program. Same for Social Security Disability. Is targeting really so bad?

J.M.: I think it makes sense to make a distinction here between targeting and means-testing. I don't think we should just do UBI and nothing else (though I do think UBI is a good idea). Universalist social democratic welfare states do a lot of targeting based on broad categories: children, elderly people, people with disabilities, students, caregivers, and the unemployed. These groups, aside from the special case of unemployed people, are groups that shouldn't be working, but who receive no labor income. This leads to a large amount of inequality across households, as those with more dependents are pushed into poverty. So programs like social security should be considered universal within the relevant target universe (old people, in that case). We should follow the same logic for the other categories, by doing things like a universal child allowance. Introducing means-testing to this sort of program adds complication without much point. In the case of a child allowance, a means-test is essentially putting a tax (embedded in the welfare code) on high income people with children, but not applying that same tax to high income people without children. It's more efficient and more progressive to just do a tax on all high income people that raises as much as the equivalent means-test would (as they say, broaden the base and lower the rates).

In terms of the covid response, the SuperDole was one of the best policies we've implemented in a few decades (we *reduced* poverty during mass unemployment!) and I was definitely frustrated by the posts on twitter about how people just got one check. But the checks were also extremely good, and I think the backlash to the SuperDole-erasure sometimes missed this. By some measures, the checks actually had more dollar for dollar poverty reducing power than the unemployment insurance (UI), because poverty is concentrated among people who are out of the labor force, and thus not eligible for UI. Broad-based checks are a good way of getting cash to the "undeserving poor" that usually get excluded. But it shouldn't be a competition between the two, they both serve distinct purposes. UI may not be as progressive as UBI/means-tested welfare (which are basically the same thing, but with the taxes in different places), but UI serves the important purpose of providing stability and smoothing income shocks, and that was probably the single most important thing to do during the pandemic. It also serves an important labor market function, improving job matching and giving workers the power to hold out for better jobs. In terms of what all this tells us about universalism vs targeting, it's kind of funny that technically speaking, UI is considered a universal benefit (it's insuring everyone's income against job loss, and even individuals in high earning households are eligible), while the checks were means-tested (albeit at the very top of the income distribution). But in practice the politics of those programs were reversed. This fits with my general theory that the more people a policy visibly helps, the more popular that policy will be. The popularity of the checks ended up creating pressure that got more cash to the neediest people in the country, so I'd count that as a win. We are going to end up having one of the best welfare state responses in the world, and significantly more progressive than countries like Denmark that focused much more on flat income replacement (though part of that is accidental due to our outdated UI systems).

In terms of places where means-testing makes sense, I think the idea should be to build a comprehensive set of universal systems that provide a foundation for people's lives, and then if there are a few programs like Housing First where means-testing makes sense, that's all well and good. Social democratic countries like Sweden still have some means-tested last ditch assistance programs, but they only spend .3% of GDP on them compared to our 2.5% of GDP, because the universal programs on top of them prevent people from needing them in the first place. I think the problem is when people see poor relief as the be-all-end-all point of the welfare state, when a good welfare state does so much more than that.

N.S.: So you have this pretty cohesive policy program and ideology here. A couple questions about that. First, do you consider this a socialist program? Does that word matter?

I notice you've been ferociously attacked by a few online socialists who don't like your program. What's going on there? Is this just a function of the fact that the Left is always splintered and prone to doctrinal infighting? Is it a function of the toxicity of Twitter? Or are there real big substantive disagreements between socdems and other leftist groups? If so, how would you characterize those disagreements?

Also, it's really interesting (and to me, inspiring) how many young people on Twitter are "taking the Medlock pill", and how you've managed to get inside the heads of many of the top econ/politics Twitch streamers. How did you do that? Do you think your sort of relentless, friendly, positive, substance-focused style will eventually crowd out the shouting, denunciatory style that we've come to expect from policy arguments on Twitter?

And finally: What's next for Medlock Thought? A book? A podcast? A subreddit? Where does this budding movement go from here?

J.M.: While I'd consider myself a socialist, I don't think the welfare state is inherently socialist. I think my general outlook could be shared by socialists and non-socialists alike. But I think it's worth remembering that social democracy was initially a socialist project, led by revisionist marxists backed by strong labor movements. It's arguably the most successful socialist achievement and I think socialists should take more credit for that. The current Nordic countries aren't full socialism, but they still have quite high levels of social ownership, and I think it makes sense to look at these things on a continuum. I really like early Swedish social democrat Ernst Wigforss' idea of the "provisional utopia", a sort of middle ground between dogmatic utopianism and incrementalism that loses sight of bigger goals. In a democracy I don't think you'll ever necessarily reach a pure end point, but I think it's really good and important to have a flexible utopian vision that provides a guide for incremental progress.

In terms of conflicts with other online lefties, honestly I feel like I'm pretty friendly with a lot of different folks across the ideological spectrum, and beyond normal lefty factionalism, there's a lot to agree on about things like building worker power with unions and the welfare state. But I think it's inevitable to get some haters the more prominent you get on the internet. There are some lefties who would rather be part of an obscure but exclusive counterculture than win any real material gains, and I've also been developing some centrist haters who seem to identify with centrism for centrism's sake. It's hard not to find the whole thing really funny, people just getting fuming mad at a friendly pseudonymous guy with a Karl Polanyi avatar talking about how great taxes and welfare are. I don't think that style will ever really crowd out being mad on the internet, but I do recommend it, tends to be a better way of convincing people of things in my experience. As for the twitch streamers, that was surprising to me because I don't really watch streams/videos, but some of my zoomer friends are more hooked into that world and so I guess that's how that happened.

In terms of next steps, I plan on doing a regular blog soon, and maybe a patreon/substack type thing. I still work full time, and so I'm hoping to cut back on hours so I can dedicate more time to posting (this, to me, is the american dream). I'm also in talks with a few think tanks about writing policy papers, so keep an eye out for those later this year.

N.S.: So basically, we’ll be seeing lots more of Medlock Thought in the years to come?

J.M.: That’s right.

That's right.

While I think I’m probably “neoliberal”, Medlock regularly pressures and shifts my left limit more and more.

Which, as this interview seems to capture, is exactly what he wants to do.