Interview: Arvind Subramanian, former Chief Economic Advisor to the Government of India

Everything you wanted to know about India's economy.

In terms of economic development, India is now the most important country in the world. With 1.4 billion people, it will soon eclipse China as the world’s most populous nation. And although India has made huge strides in reducing extreme poverty over the past four decades, almost half of the population still lives on less than $3.20 a day. So the question of how to sustain India’s growth is essential to the future of human flourishing. And on top of that, whether India can continue its economic rise will determine its future as a great power — and thus, the future of geopolitics.

When I want to understand India’s economy, I turn to Arvind Subramanian. From 2014 to 2018, he served as the Chief Economic Advisor to the Government of India. He’s also an accomplished academic economist, who has worked at Ashoka University, the IMF, and the Peterson Institute, and is currently working as a Senior Fellow at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University. My personal favorite research of his is a series of papers where Subramanian and his co-authors demonstrate that developing countries have started to catch up with rich ones. He has also written a number of books, the most recent being Of Counsel: The Challenges of the Modi-Jaitley Economy.

In this interview, I ask Arvind every big question I can think of regarding the Indian economy — how it got to where it is today, what the situation is now, what the stumbling blocks and challenges are, the best policies to meet those challenges, and so on. I learned a lot, and I hope you do too!

N.S.: Let's talk about India's economy. In a nutshell, what's the situation there now?

A.S.: So, big picture, abbreviated history.

India had more than 3 decades of really rapid growth beginning, late 1970s-early 1980s. Per capita GDP growth averaged close to 4.5 percent and as I wrote in a JEP paper (co-authored with Rohit Lamba: https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jep.34.1.3), India's dynamism was quite remarkable by cross-country standards. Poverty rates declined, access to goods and services increased sharply, public infrastructure improved. And dynamism was especially marked for close to a decade between 2003 and 2012 when India may have grown even faster than China. NPR had a even coined a catchphrase—“the world’s fastest growing, free-market democracy”—as its way of encapsulating the world’s admiration, even astonishment, as India seemed to vault effortlessly from a nation mired in poverty into a modern high-tech, car-owning middle-class society. China was the world's factory but India was going to be its back-office. That was the expectation.

In the decade after the global financial crisis (GFC), especially after 2011, growth slowed considerably. Of course, there were exogenous factors as the world economy slowed down and globalization went into retreat. But India's growth slowdown was sharper than for other countries, reflecting India-specific factors.

Initially (2011-2014), it reflected macro-economic mismanagement, corruption and decision-making paralysis which led to the near-crisis of the 2013 Taper tantrum. Later (post-2014) it reflected the inability of the government and central bank to address India's Twin Balance Sheet challenge: over-indebtedness of corporates and the counterpart rising NPAs in the banking system which had financed much of the infrastructure boom of the oughties. This was a classic Japan-style problem that India did not really solve (and truth be told, did not even really embrace as diagnosis). Private investment and credit growth have been virtually flat in the last decade. And export growth was weak too.

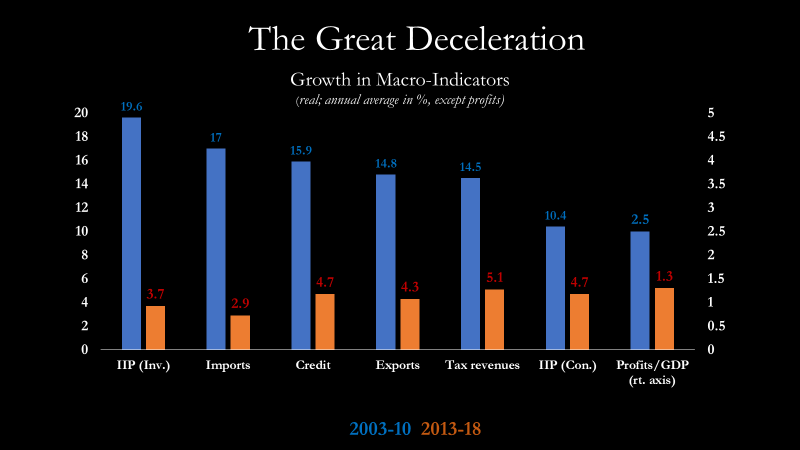

This chart captures what happened in the first 2 decades of this century:

Heading into the pandemic, India had a weak economy. So, the impact of Covid was especially hard for India, in part because the lockdown (in 2020) was amongst the most severe but also because the economy was already weak. The labour market has been especially badly affected. Informality means that measuring unemployment is tricky. But demand under a major, national employment guarantee program--reflecting reduced employment opportunities elsewhere in the economy--ran very high, well above pre-pandemic levels. And the SME sector was severely affected by 3 shocks--first demonetization, next the implementation of a nation-wide VAT (otherwise a terrific reform, called the GST) and then the Covid-related lockdowns.

As India emerges from the pandemic, the big challenge is: how do you revive private investment and trade (the long-run engines of growth) and in a manner that creates jobs?

N.S.: Great big-picture summary! OK, now let's zoom in on those eras one by one. What did India do right in order to accelerate its growth in the late 70s and early 80s? That's not an era we hear much about; most retrospectives seem to focus on the liberalizing reforms undertaken by Manmohan Singh as Finance Minister in the early 1990s.

A.S.: Exactly. This is the puzzle that Dani Rodrik and I explored in our paper (http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.498.7043&rep=rep1&type=pdf): namely, why growth took off nearly a decade before the justly-famous liberalizing reforms of Dr. Manmohan Singh triggered in the aftermath of India's balance-of-payments crisis in 1991.

It seems clear that the break in the Indian growth process occurs around that time. Between 1950 and 1980, per capita GDP growth was close to 1.5 percent (famously called the "Hindu" growth rate) but in the 1980s and 1990s, it averaged about 3.5-4 percent.

Our explanation is that India undertook what we called pro-business reforms, distinguishing it from the pro-markets reforms of the early 1990s. Essentially, for domestic producers and incumbents, greater freedom was given to operate (the onerous restrictions on them were gradually eased) and they were given greater access to foreign inputs, technology, and foreign exchange and all this without really opening up the economy to foreign competition (Non-tariff barriers came down some but tariffs didn't decline much in the 1980s and trade did not take off either). And we argued that because India was so far away from its income possibility frontier that there was a big bang for relatively modest pro-business reforms.

It didn't hurt that, at the same time, the government embarked on massive fiscal expenditures that amounted to Keynesian pump-priming on steroids. Of course, this fiscal stimulus led to large current account deficits financed by foreign borrowing and eventually to a depletion of reserves. Along with other proximate triggers (oil price rise, non-resident Indian investors withdrawing their investments), and a fixed exchange rate regime, India experienced what might be characterized as a classic Krugman-esque first-generation BOP crisis in 1991.

The unsettled debate between us and the critics was whether the growth take-off was due to unsustainable fiscal profligacy of the 1980s or also in large part due to the pro-business reforms of the 1980s.

Now, why did the modest reforms and the profligacy happen? Essentially, because politics started to become more competitive. The Congress Party's monopoly on power at the Center (what you would call the federal level) was broken in 1977 in reaction to Mrs' Indira Gandhi's imposition of the Emergency and the suspension of democracy in 1975. A chastened Mrs. Gandhi returned to power in 1980 but without the guarantee of political dominance: as a result she became more populist (resulting in the macro-profligacy) and had to court business for electoral advantage which forced the pro-business reforms.

The political economy of these pro-business reforms in India of the 1980s had a counterpart in the early Deng actions in China in that both were not hugely disruptive and hence politically incentive compatible ("reforms without losers"). In China, incumbents (in agriculture and the township and village enterprises (TVEs)) got to keep the marginal gains from liberalization. In India, incumbents got benefits without being exposed to competition.

N.S.: That's great! It suggests that the right approach to development policy is a pragmatic, eclectic one, rather than a commitment to an ideology of free-market liberalization. A process of "crossing the river by feeling the stones", to stick with Deng quotes.

OK, so how about those liberalizing reforms that Singh did in 1991? Did those actually have a big additional effect, on top of the pro-business reforms of a decade earlier?

A.S.: Yes, the Singh reforms were a real structural break from the dirigiste past--trade and FDI were liberalized; the exchange rate became more flexible; firms were freer to raise capital, industrial licensing was dismantled. Then came a second wave of reforms in the late 1990s/early 2000s which opened up a number of sectors, especially telecommunications, airlines, banking, power, and also provided a big push on infrastructure, rural and urban. India also started making the transition from the state as operator/producer to the state more as a regulator.

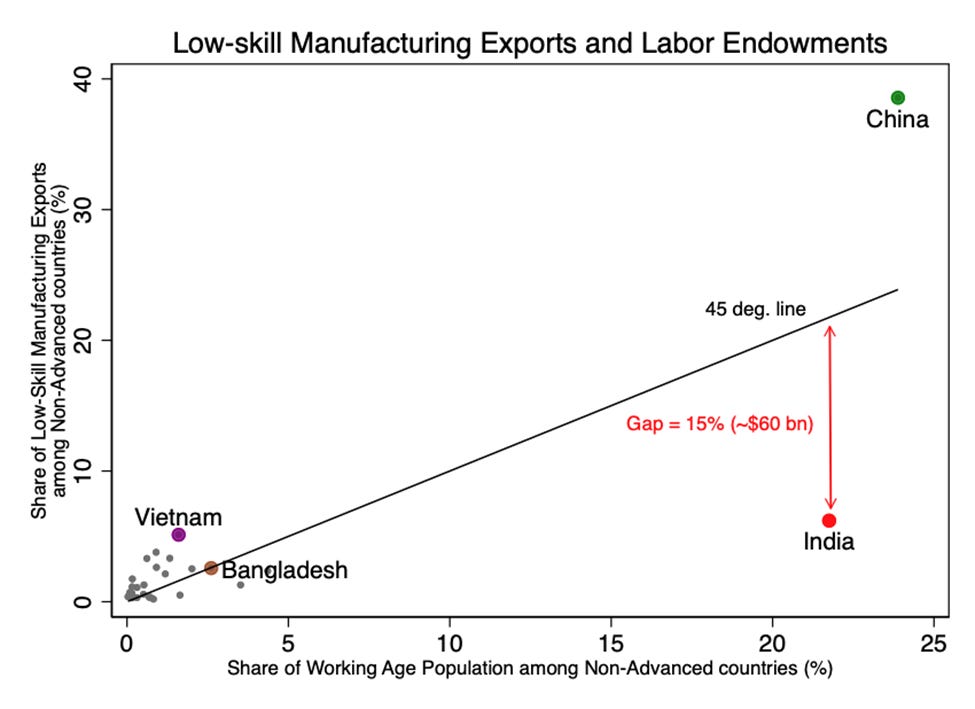

The consequences were enormous. The 1990s and 2000s saw rapid growth, large reductions in poverty, increased availability of goods and services, and also witnessed an expansion of educational opportunities partly in response to the boom in the economy. And less recognized, something that Shoumitro Chatterjee and I discovered (https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3713234) recently is that for nearly 25 years, the development model was basically East Asian with one important difference. The similarity was double digit export growth (third highest in the world) not just in services but also in manufacturing. The difference was that export growth, even in manufacturing, was based on defying rather than deifying comparative advantage, in being concentrated on more skill-intensive activities. A sort of negative way of illustrating this--and we find this chart telling--is to do a cross-country comparison (amongst developing countries) of the share of unskilled-labor intensive exports versus their share of the global labor force. India and China are striking outliers but in opposite directions.

This partially explains why despite rapid growth and all the gains, including in poverty reduction, there was less structural transformation and less equal sharing of the gains than perhaps occurred during the comparable growth phase of the east Asian countries. The current zeitgeist--the backlash against neo-liberalism--tends to highlight the latter but also tends to overlook the huge gains that were achieved in the 3 decades of the dismantling of the socialist Raj. Of course, our current view of those boom years (1980-2012) is inflected by the experience of the last decade when a combination of slowing reforms, policy inadequacies, and a less favourable external environment changed the pace of the Indian growth juggernaut from torrid to tepid.

N.S.: Now, the common criticism of this period of post-1991 Indian growth is that because it focused on services and on more skill-intensive manufacturing, it didn't create as much broad-based employment as the typical labor-intensive manufacturing development model. Is that a problem? And if so, have there been steps to add more labor-intensive activities to the mix? If so, how are those working out?

A.S.: Patterns of specialization are determined not by any one set of actions in any one period; they are the cumulative result of history. And in India's case, they owe to all the policies from the 1950s onwards that raised costs and cosseted inefficiency (tariff barriers and licensing), that penalized size (activities exclusively set aside for the small scale sector as well as blunt production limits and anti-monopoly laws), and that favored higher education over basic education. Reflecting these factors, India's employment share of manufacturing has always been low, especially in formal manufacturing. In some ways, the slew of policies converted an unskilled labour abundant country (in quantity endowments) into a skilled labor intensive country (in cost terms). Tsieh and Klenow have shown that Indian firms tend to be small (relative to US and Mexican counterparts) and Indian industry exhibits limited churn. Indian capital today is uncomfortable with having too big a payroll which undermines its competitiveness globally in labor-intensive sectors.

The role of conjunctural factors should also not be overlooked. The IT-services revolution owes to an accidental sequence of events, including the relaxation of US immigration restrictions in the 1960s and expansion of the H-1B visas subsequently, the early investment in India's educational centers of excellence (the famous technology and management schools, IITs and IIMs, respectively) and English language proficiency (the colonial inheritance). When the IT revolution occurred, Indian talent had acquired not just a foothold but also a reputation in the US which then gave comfort to US firms to tap the English-language speaking talent pool back in India.

Reversing this long-standing specialization will be difficult. But it is not obvious that the government's new strategy goes in the right direction. Its new industrial-cum-trade policy involves promoting domestic champions (mostly in non-tradables unlike the Korean chaebols which had to prove the test of efficiency by exporting), offering production subsidies (mostly in capital and technology-intensive sectors rather than labor-intensive ones), raising tariffs and staying out of regional trade agreements, especially the ones in Asia (RCEP). This is unlikely to be a recipe for a labor-intensive export boom.

N.S.: Well let's talk about a couple of those factors. Why isn't India's basic education particularly good? Also, why are Indian companies uncomfortable with large payrolls?

Another factor I've heard other people mention is infrastructure. For a long time it seemed as if India had a vetocracy in place that prevented it from building good roads and other transport infrastructure that's necessary in order to move goods quickly from place to place. But I've also read that Modi's administration has gone on a building boom, and national infrastructure is finally improving. Is this true?

A.S.: The shortfalls in basic education go back a long way. One of the puzzles of Indian development and democracy is why the early leadership did not push strongly for spreading primary education. Under the Indian constitution, education was the responsibility of the states rather than the federal government and the latter was reluctant to get involved because of language diversity and the tricky politics around it in the early years. One persuasive structural explanation goes back to the late MIT political scientist, Myron Weiner, who looked at child labour and basic education and argued that in India's deeply hierarchical society, the elites, who were both educated and upper caste, were not really committed to the spread of education nor incentivized to do so. Historically, this spread has had a lot to do with religion (the US and Europe) and ideology (for example, China and Korea) with motives including transmitting beliefs (communism), creating a sense of nationhood (France) etc. And those wellsprings of action were not strong in India. Interestingly, the places in India where education did spread, most notably in the southern state of Kerala, a combination of enlightened rulers and strong anti-caste reform movements (before independence) and a committed communist government (post-independence) played a big role, which is consistent with the broader historical experience.

Things started to change in the 1990s. As the political scientist Akshay Mangla, argues in a new book, the elites, converted to the cause of education because of seeing the costs of India falling behind other countries and possibly also prodded by international actors, nudged the government into more serious action. It also helped that when growth took off, the returns to education, and especially English-language proficiency, became more evident which helped on the demand side as well. As a result, primary and secondary school enrollment have made great advances. Increasingly, the debate in India, as elsewhere in the developing world, is about learning outcomes not enrollment and attendance. And here the news is sobering because they are not just not improving but actually declining, as recent work by my CGD colleague Justin Sandefur and his colleagues has shown.

On infrastructure, since the late 1990s, things have really stepped up. It began with the government constructing rural roads and highways connecting the major cities. This was followed in the 2000s by a major private sector-led push across the board not just in roads but ports, airports, power and telecommunications. And the Modi government has continued this infrastructure thrust.

Great strides have not just been made in physical but digital infrastructure. In 2015, I coined a term JAM which represented the coming together of financial inclusion (the J from the Hindi "Jan Dhan"), biometric identity (the A for “Aadhaar”) and telecommunications (the M for mobile). The government has used this trinity for a variety of purposes, including making direct cash transfers to the poor. In addition, a public-private partnership has created a digital, non-proprietary platform called the Unified Payment Interface (UPI) which is driving a lot of private dynamism and innovation in a number of sectors--finance, tourism, e-commerce, software solutions etc. I like to joke that India is creating unicorns roughly at the rate that it is creating chess grandmasters. While cause for cheer, this dynamism, based on skill- and technology-intensive factors of production, cannot drive structural transformation because that requires creating jobs for India's vast, relatively less skilled labor force. And India's job situation, especially after the pandemic, is sobering.

Which leads to your question about why India has not really managed to achieve scale in its manufacturing operations and why Indian capital is reticent in doing so. I suspect, although I am not sure, that there is again a lot of path-dependence here. For a long time under the license Raj, domestic entrepreneurship was penalized. And there was a particular aversion to size, fearing the economic and political power that large firms could wield. There is a strong view that India's labor laws have militated against size but there is not a lot of convincing evidence to support that particular claim even though the larger point that the whole ecosphere of laws, regulations and practice penalizes size is probably true.

Ironically, that very Raj spawned what I call "stigmatized capitalism," the suspicion that firms that have prospered have done so not because of intrinsic merit but because of their proximity to government. The consequence is that in any potential conflict between labor and capital (whose probability rises with larger payrolls), the state cannot afford to be seen to come down on the side of tainted capital. So, paradoxically, labour feels vulnerable to the power exercised by large firms but equally capital does not feel protected by the state either. So, we are in a bad equilibrium that favors small over big.

N.S.: What about foreign capital? That certainly doesn't favor small over big. Are there big opportunities for foreign manufacturers to scale up big operations in India now and make good money?

Also: It occurs to me that China used a strategy of local industrial policy in the 80s through the 00s. They told regional governments to boost growth, gave them a ton of power to do so, and then stepped back and basically let them experiment. Could India do that? Are they overly centralized?

A.S.: In principle, the constraints on foreign firms--by way of the regulatory environment--are no different from those on domestic firms. If anything, like in most places, foreign capital is always more vulnerable to discriminatory treatment, not necessarily brazenly, but subtly. So, while they may want to scale up, they may be no more able to do so than domestic firms. And, if foreign investment is of the tariff-jumping variety, targeting the protected and seemingly large domestic Indian market, even the incentive to scale might be dented.

On your great China question, there was a period when the comparable dynamic was at play in India. We called it competitive federalism, where the Indian states would attempt to lure investors--domestic and foreign--to their jurisdictions with the enticement of tax breaks, an easier business environment, and uninterrupted power supply. The current Prime Minister famously did it when he was the chief minister of the state of Gujarat; another politician successfully attracted IT firms to Andhra Pradesh (which has since been bifurcated); and the auto and auto parts industry was lured to the state of Tamil Nadu. And in the current environment, Bangalore is the hub of the new unicorn revolution, reflecting the agglomeration benefits of exploiting the rich ecosphere built around India's largest IT firms that are located there.

That competitive federalism dynamic has become less salient, I suspect because the overall growth environment has lost its luster and in part also because things have become more centralized politically. In fact, one could argue that the weak growth environment has converted competitive federalism into a competitive populism whereby state leaders are trying to outdo each other in terms of promises to cash transfers, free power, and a whole slew of subsidized goods and services etc. And, as the political scientists Yamini Aiyar and Neelanjan Sircar have argued, the political centralization has affected the ability of state leaders to do things on their own and get political/electoral credit for it.

N.S.: Let's talk about populism. Is redistribution, rather than growth, the thing the Indian populace is interested in most today? And how is the Modi administration doing on that front? I've heard that there has been good progress in rural sanitation; is that accurate?

A.S.: Gauging what the "populace" is interested in or wants (i.e. their preferences) is, as you know, very difficult. But what is clear is that Prime Minister Modi has established, very successfully, at the national level, a new strategy or idiom for redistribution-cum-inclusion which we called "New Welfarism." (https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/national-family-health-survey-new-welfarism-of-indias-right-7114104/)

Several features of this are noteworthy.

First, what New Welfarism is not about. It does not prioritize the supply of public goods such as basic health and primary education as governments have done around the world historically and which successive Indian governments had not until the turn of the 21st century. It is also somewhat ambivalent about strengthening the safety net which the previous Congress government did by establishing a national employment guarantee scheme and enshrining in law the right to subsidized food.

Second, what New Welfarism is about is the subsidized public provision of essential goods and services, normally provided by the private sector, such as bank accounts, electricity, cooking gas, toilets, housing, plain cash and, more recently, piped water.

Third, New Welfarism has been successful economically and politically. Recent survey data show that access to these goods and services has increased substantially (Chart: Percent of Households with Access to These Goods). The government has tended to over-hype the achievements but even discounting for that, the gains are real. For example, no Indian leader has dared to speak so openly about open defecation and make it worthy of attention and action.

These gains have yielded political success. Part of the strategy--through careful and unrelenting messaging--has been to ensure attribution: that these goods and services have been due to the PM's efforts and interventions; and the fact that these are tangible (rather than education and learning, progress in which is much more difficult to assess, let alone divine its source) helps in the attribution strategy. And, so far, the populace appears to have bought this. To be clear, the government's political success is not all due to New Welfarism; social and cultural issues have no doubt played a big role. But promoting welfarism and playing on identity do not have to be mutually exclusive political strategies.

Fourth, one irony is that welfarist populism did not begin with Mr. Modi because its origins go back to state leaders in the south who inaugurated it several decades ago. Mr. Modi has embraced and refined it with both conviction and calculation.

Now, this strategy is once again being emulated by state leaders around the country. In recent and upcoming state elections, there is a frenzy of competitive populism with candidates trying to outdo rivals in what free goods and services are promised and how much. As democracy in action, the imagination and inventiveness around this strategy elicits both awe and anxiety.

Fifth, of course, there is a populism to all of this that distracts attention away from the focus on improving state capacity, enhancing growth-oriented policies and reining in spending and deficits but New Welfarism is not all populism. In fact, even the term Welfarism takes away from the fact that some of what is provided really adds to the basic quality of human lives. In fact, it is not dissimilar in spirit to the Basic Needs-as-Development strand of thinking that was popular in the 1970s.

Finally, it is no co-incidence that the current enthusiasm for competitive populism comes against a backdrop of weak growth and a shrinking pie and opportunities. At some point, budget constraints will start to bite, putting limits on New Welfarism. There is no substitute for re-invigorated growth and employment-creation as the durable way of improving the welfare of all Indians, including and especially the poor.

The one piece of good news is the recent political success of a party called Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) that, uniquely in Indian history, has made the public delivery of basic health and education its political calling card. If this dynamic spreads that would truly be a game-changer for human capital investments and outcomes.

N.S.: Let's talk about Modi a little more. This is a third rail on social media, where pro-Modi and anti-Modi people will swarm you no matter what you say. But we can't talk about the Indian economy without talking about him, so let's do it!

India's GDP growth began to slow noticeably around 2016, the same year that Modi conducted an experiment with demonetization. Was demonetization the cause of the slowing growth, or was it unrelated -- perhaps the delayed effect of bad loans in the banking system?

A.S.: Yes, demonetization takes us into hot and murky waters. But before we do that, I want to correct your assertion/assumption that growth started to slow down around 2016. As you know, I am not very comfortable with India's GDP (and consumption) statistics post 2004, so you need to look at a whole set of alternative macro-indicators to get the timing right. Here is one chart on real credit growth but the pattern (also shown in an earlier chart) is broadly similar if you look at real investment, exports, and imports, profits, capacity utilization etc.

And that pattern is a boom in the 2000s and sharp deceleration after the global financial crisis, especially after 2011/12. So, that is when it starts and the reason for that slowdown is a combination of the external environment becoming less buoyant and policy inadequacies under the previous government, especially between 2009 and 2012, including loss of macro-economic control, corruption, anti-investor actions etc. But the slowdown endures throughout the decade because of the overhang from the boom period that we called the Twin Balance Sheet problem which was only feebly and tardily addressed. All this is to say, that demonetization is not the event that separates the boom from the slowdown.

But then to your question, what was the impact of demonetization? In the short run, there was enormous pain and hardship inflicted especially on poorer households and small firms in the informal sector (and parts of agriculture) because demonetization was a severe tax on cash-intensive activities; there was also some adverse effect on the labour market.

The real puzzle is that it is hard to detect a large and durable impact on overall economic activity as Amartya Lahiri discusses in his Journal of Economic Perspectives piece on demonetization. In fact, if you go back to the chart you will see a rebound, albeit short-lived, in activity a year after demonetization. And this shows up in other indicators as well.

But a few other things should be kept in mind when evaluating demonetization. Its short run objective of penalizing holders of illicit wealth in the form of cash had very limited success because all the demonetized cash came back. Its longer term objective of reducing cash in the economy has also not been achieved because today the cash-GDP ratio is in excess of the pre-demonetization level. Its objective of promoting digitalization has occurred in spades but that is less due to demonetization and more due to the dramatic, overall improvement in India's digital infrastructure.

One reason demonetization still looms large in the imagination is that the small scale informal sector has suffered in the last five years but that has owed to three shocks specific to this sector: demonetization was the first but it was followed by the introduction of the national VAT and then the Covid shock.

Leaving aside the costs inflicted on the poor and small firms which were first order, the aspect of demonetization that was really significant and certainly upended all my understanding of the political economy of reforms, was its political impact. I discuss this in my book Of Counsel. There was a major election a few months after demonetization where this was arguably one of the big issues; and in that election, the ruling party earned a landslide victory. The argument I make is that inflicting so much cost on so many people, far from hurting the government probably ended up helping it. So, it may have been that inflicting hardship–perhaps not by intent but certainly as consequence–was a feature not a bug of demonetization. Political economy folks need to figure that one out.

N.S.: So what should be the Modi administration's top economic priorities right now?

A.S.: As you know, these lists are always daunting to respond to possibly because they end up being reductive in both diagnosis and prescription. With that caveat, let me wade in.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has, of course, thrown up new challenges. One would expect the Indian government and business to scent significant opportunities here. One expects that responses (sanctions) to the Russian invasion will increasingly force investors to be more sensitive to the nature of political regimes where they operate, intensifying already-existing pressures to shift production out of Russia today and possibly China tomorrow. Similarly, access to foreign markets for goods exported from such regimes has also become more uncertain.

Against this background, a democratic India should be, and see itself as, more attractive to the fleeing investors. Surprisingly though, there is growing concern that India itself might be targeted in the future for similar actions by the West. The argument is that if the US can act against Iran or Venezuela or Russia for geo-strategic reasons, pretexts can always be found for freezing Indian assets in the future or raising barriers to Indian goods and services. Talk has therefore begun about indigenizing payments systems to reduce reliance on the dollar-based system, diversifying foreign exchange reserves and negotiating barter trade agreements.

Such costly deglobalizing actions would be in keeping with and even re-inforce the government’s inward turn. In the last few years, India has raised tariff barriers, implemented selective industrial policy and stayed out of integration agreements, especially in dynamic Asia. Freer trade and more intensive economic engagement with the world now risk becoming serious casualties of recent developments. So, one policy suggestion would be to do exactly the opposite: India should perhaps see recent developments as a real new opportunity and reverse the inward turn.

The other suggestion is more difficult to itemize. In our recent Foreign Affairs piece (https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/india/2021-12-14/indias-stalled-rise), Josh Felman and I talk of defective software of policy-making as being the critical problem afflicting economic management. Fixing this does not translate into one or two concrete actions. It is about a broader policy approach or sensibility that requires a number of fixes.

Restoring the credibility and integrity of official data, which in recent years has been problematic.

Making the playing field level between investors especially since in recent years the perception has gained ground of India being infected by what we called the 2A variant of Stigmatized capitalism which is a euphemistic way of describing the government championing the 2 largest conglomerates in India, owned by Mukesh Ambani and Gautam Adani.

Working more cooperatively with the states because in India the remit for almost any thorny issue--agriculture, power, the Goods and Services Tax--is the joint responsibility of the central (federal) government and the state governments.

Avoiding policy inconsistency. In a number of areas--bankruptcy, taxes, regulation--policy has reversed itself to the detriment of investor sentiment.

Finally, preserving the independence and integrity of independent institutions and thereby upholding rule of law. Political scientists such as Pratap Mehta have written about the Indian Supreme Court, which should act as a powerful and important check on executive actions, but has been ineffective in doing so. In macro-economics, in recent months there is a real anxiety about fiscal dominance, something that Viral Acharya has written about. Interest-revenue ratios are so high in India (almost 40%) that despite inflation running above the upper range (6%) of the central bank's inflation target the anxiety is that the central bank may be less than totally vigilant about fighting inflation because of having to contain the government's borrowing costs.

N.S.: In fact, let's talk about the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and how this impacts India. First of all, India has bought a significant amount of its current stock of weapons from Russia, and those need to be serviced and maintained, even if India switches to buying new weapons from the U.S. and NATO countries. Will the sanctions on Russia interfere with that?

Next, do you see India taking advantage of Russia's inability to sell oil and gas to Western countries? With those markets closed and with Russia desperate for foreign exchange, it seems like India might be able to buy oil and gas from Russia at a steep bargain. And perhaps Indian companies could even acquire Russian assets on the cheap, if they can outcompete Chinese buyers. Do you foresee anything like that happening?

A.S.: These questions are beyond my scope of expertise. But broadly the facts are that India's dependence on Russia is more a stock problem--the need for supplies and parts for about 60 percent of its equipment purchased over several decades. India has been diversifying away from Russia in flow terms, especially toward French, Israeli and US equipment. One major exception to even the flow point is the recent purchase of the S-400 missile defence system on which the US will have to take a call about imposing sanctions. Ashley Tellis of the Carnegie Endowment believes that India’s defence cooperation with Russia is unlikely to weaken soon. Without doubt Russia’s military capability will be degraded because of its invasion and the resulting sanctions. But its ability to continue supplying parts and equipment to India will only really be knowable with time. A State Department official claimed in early March that India had cancelled some military orders from Russia but this was not confirmed by Indian officials. It seems more likely than not that India will diversify away from dependence on Russia.

On your second point, India has recently increased its purchase of Russian oil at reportedly discounted prices but that was clearly an opportunistic strike given oil prices and their critical impact on the Indian economy and the budget. A bilateral rupee-rouble trading mechanism is once again under consideration. Since India runs a trade deficit of about US$ 3 billion in 2020 with Russia that might not be unattractive. But there is still considerable uncertainty about the scope of Western sanctions and their collateral impact. I doubt India or Indian companies will rush into further economic entanglement with Russia, certainly not any time soon.

N.S.: OK, two final questions. First, if you were advising the Biden administration and other U.S. policymakers, what would you say we need to do in order to help India develop effectively?

Second, if you were advising Western investors on investing money in India, what would be your advice?

A.S.: To state the obvious first. India's development will be successful or not based mostly on what happens domestically. But the outside world and the US does matter too. It is worth repeating ad nauseam that the era of developing country convergence that Dev Patel, Justin Sandefur and I (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S030438782100064X?via%3Dihub) documented was also the era of hyperglobalization. So, at a 30,000 feet level, the US must remain open to goods, services, people and students to be both a model and a magnet for the world. That may be necessary (even if insufficient) for India to continue seeing the world as an opportunity. The worry is that polarization and paralysis in the US might come in the way of doing the things domestically that are necessary for sustaining an open liberal economic order. Polarization and the policy volatility that it generates (imagine US policy towards Russia had Trump remained in power) also risks making the US a less reliable partner.

But the good news (and the exception to that polarization) is the broad bipartisan consensus in the US on the need to further the India relationship which is related (but not limited) to the converging strategic interests on managing the rise of China. The economic, and especially the trade, relationship has, however, been more wobbly. Post-Russian invasion of Ukraine, the US has a chance to cement the first and improve the second.

Collaboration on research, science and especially military/defence technology should be intensified and the US needs to find ways of addressing its own arbitrary rules and procedures that come in the way of easier sharing of critical technologies and hardware. Clearly, India needs to reduce reliance on Russian arms but the US and Europe need to facilitate that concretely and practically by becoming easier partners themselves.

Since sanctions against Russia are raising concerns that India could be targeted in the future, the US must work toward convincing India that there is more opportunity than threat here, and that the US will help India become the hedge against the increasing unreliability of China and the Asian value chain. For example, Devesh Kapur suggests that the US could nudge/incentivize American firms to make India the next Taiwan in terms of chip/semi-conductor production capability. Of course, the Indian government will have to do its bit--quite a bit--to create the appropriate regulatory environment and assure investors that the playing field will be level.

But those are the kinds of bigger conversations that India and the US should be having. Equally though, given history and each country's interests and constraints, there should be realism about the limits of the US-India relationship: they can edge closer and they can cooperate more fruitfully together and more frequently but there will always be differences and they will never be formal allies.

On your second question, I will be honest in saying that I am terrible at offering investment advice, especially about the future and especially about India. Investors care–and should care–about the long term which is about more than just narrow financial opportunities. Here, there has to be anxiety about the kind of society India is becoming. To me, the famous “Idea of India” was always a collective, cognitive capaciousness that allowed competing ideas of India to fight and flourish, and I now wonder whether that capaciousness was more superficial and brittle than we had hoped for or even taken for granted. I am also not confident–for reasons we have discussed earlier–that India can regain the broad-based economic dynamism it achieved for about 3 1/2 decades until the global financial crisis.

But what I can say with confidence is that investors should pay attention to the entrepreneurial talent that is being unleashed not just in urban, privileged India but all over the country thanks to the digital transformation that has occurred in recent years, including under the Modi government. I said earlier that India is now producing as many corporate unicorns as it is chess grandmasters and as rapidly, and both successes owe in no small part to the democratization of digital access. Indian cricket wallowed in mediocrity for decades until the liberalizing reforms spread opportunities to the smaller towns, making India a cricket powerhouse now. Give a young Indian a cell phone and connectivity, and there are no limits--in magnitude or sphere of human activity--to what her creativity, hustle and aspiration can achieve ( “Dreamers,” a book by Snigdha Poonam, captures very well some of this spirit).

Will these millions of inevitable, individual mutinies--to paraphrase V.S. Naipaul--add up to something macro (to put it as a crude economist)? Can they overcome the long-standing deficiencies of collective action of India's state and society that Lant Pritchett and Devesh Kapur have written about? These are big and open questions for India's future.

Thank you for this interview, Noah. It's terrific.

Is there a potential quick win available from liberalizing the textile and apparel sector?

Milton Friedman wrote decades ago about the costs of protecting Indian handloom weavers (certain products, like saris, can't legally be made on mechanized looms) and yet these and other restrictive practices are still in place.

India's apparel exports are lower by value than Bangladesh's even though India has eight times the population, so clearly something needs to change.