Inequality might be going down now

Knock on wood.

One name you don’t hear a lot these days is Thomas Piketty. In 2013, the French economist burst into the popular consciousness with the publication of Capital in the Twenty-First Century. The basic thesis was that unless extraordinary forces — war, or massive government action — intervened, capitalism would naturally tend toward greater and greater inequality. That thesis was summarized by the famous and pithy formula “r>g”, meaning that if the rate of return on capital is greater than the growth rate of the economy as a whole, inequality mechanically increases. In Piketty’s telling, only the extraordinary combination of the Great Depression, the New Deal, World War 2, and rapid postwar growth managed to save us from a social collapse due to spiraling inequality in the early 20th century, and now we were back in the danger zone. Here’s the famous graph, with some labels I added:

Piketty’s book was perfectly timed to coincide with an explosion of leftist political sentiment and popular unrest. In an age where everyone needs data to back up their arguments, Piketty’s inequality numbers were something solid and tangible that people could point to and argue that capitalism was naturally unstable, and that the U.S. was in a moment of deep crisis. Progressives hammered home the message of a Second Gilded Age day in and day out — in fact, they are still hammering it home.

Inside the econ profession, meanwhile, the book sparked its share of fiery debates — the most dramatic moment was at the 2015 American Economic Association meeting, when Piketty suggested that his critics were bought and paid for by the rich. In the more staid forums of papers and blogs, economists found any number of reasons to take issue with Piketty — he ignored the costs of capital depreciation, he ignored the fact that much of the income from “capital” was actually income from land, his theory relied on some questionable assumptions about savings rates, etc. Some even argued that Piketty’s data itself was unreliable.

But essentially no one questioned that inequality had risen a lot in the U.S., even if there was disagreement on the exact amount. As long as income and wealth kept getting less and less equitably distributed in the U.S., academic criticisms of Piketty’s data and theory would remain…well, academic. Although a few stalwart defenders of laissez-faire capitalism insisted that inequality wasn’t a problem, these arguments fell very flat; most people don’t think that a society can experience perpetually rising inequality without running into some sort of major social problems.

So for a number of years, many of us thought very hard about ways that inequality could be curbed before it got completely out of hand. I was in the camp that wanted to uplift the incomes of society’s poorer members, via cash benefits and faster economic growth.

But anyway, then an interesting thing happened — inequality started going down a little bit.

The plateau and (slight) decline of U.S. inequality

First, let’s talk about wealth inequality, which tends to get a lot of press in the U.S. This is the type of inequality that the new socialist movement, as well as left-leaning economists like Gabriel Zucman, have tended to focus on the most.

As you may have noticed, stocks crashed this year (and to a lesser extent, house prices fell too). A stock crash will tend to hurt the rich a lot more than it hurts the middle class and poor, since the rich collectively own most of the stock in America. And it’ll hit the super-rich especially hard, since their wealth is mostly made up of stock in the businesses they founded. Elon Musk, the country’s richest man, has lost $133 billion this year as Tesla’s stock has fallen.

And in fact you can see this in the wealth numbers. A good source for these numbers is realtimeinequality.org, which displays data gathered by the economists Thomas Blanchet, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman. People will argue about this data, but Saez and Zucman tend to find higher inequality than others do, so these numbers are probably a worst-case scenario. And they show that the wealth share of the top percentiles took a dip this year as the market crashed:

You can see this crash, and its disproportionate effect on the rich, even more dramatically if you look at the absolute wealth numbers:

What’s also interesting is that the recent dip follows about eight or nine years of plateau, or even decline, for the top wealth shares. It seems that right around the time Piketty published his book, the trend of relentlessly rising wealth inequality that had been in place since around 1980 came to a halt.

Now let’s take a look at wage inequality. This is something that progressives aligned with the labor movement tend to look at a lot. Labor income inequality steadily rose from the late 70s through the late 2010s — right around when Piketty’s book came out — and then plateaued. The wage shares of all four quartiles of the distribution, as well as the famous “one percent”, basically stabilized, with the top two quartiles falling a bit and the 2nd-poorest quartile rising a bit.

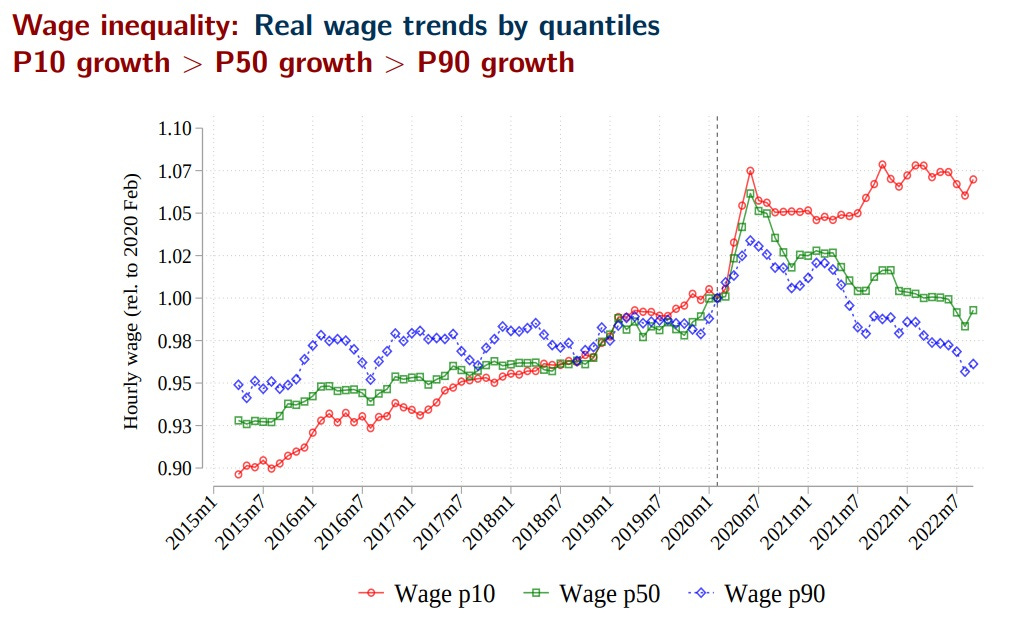

Other data sources show an even more optimistic picture, especially since the pandemic. A recent presentation by Autor, Dube and McGrew shows that although inflation has hurt everyone’s real wages, for the bottom 10% of earners the gains have outweighed the losses:

Workers with only a high school education have also seen their wages increase faster than their more educated counterparts.

As you can see on the chart, this wage compression began well before the pandemic (the red line goes up more than the blue or green). The authors find that this pre-pandemic drop in wage inequality happened entirely in states that raised their minimum wages, which suggests that policy might have played a role here.

Autor, Dube, and McGrew don’t know exactly why the wage compression is happening. They find evidence suggesting that labor market tightness — due to fast growth and the overheated economy — plays a role. But they also find evidence that job switching has increased since the pandemic, and that low-wage workers who switch jobs have seen much bigger raises. This suggests that the labor market isn’t just tighter now — it’s also more competitive.

As for total income — which includes not just wages but also rental income, government cash benefits, etc. — that’s a more complicated picture. Realtimeinequality.org shows a plateau around 2013, similar to wealth and wage inequality, but no recent compression. But a recent paper by Larrimore, Mortensen, and Splinter shows that government benefits, including Covid relief, have boosted the incomes of the poor relative to others.

It’s important to note that the drops in inequality are all very modest — only enough to cancel out the rise in inequality that happened in the years immediately following the financial crisis, and certainly not yet enough to reverse the long trend of the 80s, 90s, and early 00s. And this could also just be a temporary reprieve. But the failure of inequality to continue rising since Piketty’s book came out suggests that predictions of an imminent crisis of capitalism was overdone. This, as much as any academic pushback, may be why we don’t hear Piketty’s name thrown around as much these days.

Why is inequality going down, and can the drop be sustained?

Whether the drop in inequality will be sustained depends in part on why it’s happening. This isn’t possible to know yet, but we can start to make some guesses.

On the wealth side, the most important factor is just the stock market. In a recent post, I listed a number of reasons that U.S. stock returns could be more moderate than we’re used to over the coming decade:

These reasons include U.S.-China decoupling and deglobalization in general (meaning less opportunity for overseas profits), slower population growth, higher interest rates, a reinvigorated antitrust movement (meaning less growth in profit margins), and the fact that stock valuations are still pretty high in historical terms. If stocks do yield more modest returns over the next decade, that will compress wealth inequality further.

On the income side, policy choices matter a lot. Dube and others have shown that minimum wage increases — which, I should note, don’t seem to have resulted in any sort of mass unemployment anywhere so far — are effective in compressing wages. Whether the labor movement really manages to unionize restaurants and warehouses etc. will make a difference too, as will government cash benefits. Big factors like deglobalization and AI could have an impact too, and there’s the question of whether the Fed’s rate hikes will send us into a recession. But I think the most important factors, at least in the long term, are going to be driven by our democratic policy choices.

In other words, even if Piketty’s direst warnings were overdone — and even if the leftists who cited his research to warn of the coming collapse of capitalism were blowing hot air — there seems to have been a core of truth to what Piketty wrote. Ultimately, it was a combination of government action, a stock crash, tight labor markets, and deglobalization (if not yet major war) that curbed the upward trend of rising inequality — just as Piketty might have predicted.

But it also seems possible that this demonstrates not the fundamental instability of democratic capitalist systems, but their fundamental self-correcting stability. Stock prices can outpace economic fundamentals for a long time, but probably not forever. An economy that focuses on cultivating highly educated workers will eventually find itself more in need of laborers, and their wages will rise. Globalization can progress for a long time, but eventually export markets and overseas investment opportunities get saturated. And if low-end workers get the shaft for long enough, eventually they’ll get mad and come together to vote for increases in wages and benefits.

And perhaps people like Piketty, who arrive at the peak of inequality to issue dire warnings, are themselves a crucial part of the stabilization mechanism that brings inequality back down. I hope so, anyway. Knock on wood.

Update: Here are some other numbers from Michael Strain and John Voorheis showing a plateau in wage inequality in the early 2010s and a drop beginning in the late 2010s. Strain also points out that the Gini coefficient of income after taxes and transfers also stopped going up around the early 2010s.

Extrapolating a single, small downtick as a reversal of a trend? That's honestly pretty sloppy, Noah. You, of course, have qualified your thesis with a "might," but the tone here is still a little too much one of vindicated optimism for a case that's actually pretty weak.

Look at the inequality graphs you shared. Were they smooth lines trending upward without interruption until now? You could have taken a slice out of the same graphs at 2001-03 or 2007-09, where inequality fell far more dramatically (due to recessions/bear markets), as "evidence" of a reversal, too. And yet you didn't. Because you know that the *secular trend* continued right after both declines, didn't it?

Nor did you note the similar-sized declines in inequality during the early 90s. Because, again, they were just temporary blips in the super-cycle of increasing wage/wealth inequality from the 1970s through now.

Now, aren't we now in a similar such (at least technical) recession?

Conversely, what if you had written this same essay between 2020-21? I didn't hear that much about Piketty then, either. Did you? Despite the fact that inequality by some measures shot up faster than anytime in my lifetime. A ripe moment, especially, for "r>g!" Maybe Piketty's relative absence was because there were certain other things for Twitter people to talk about at that time, and not because his thesis was discredited or overstated by reality (quite the opposite)? Maybe in 2022, when inflation and the largest war in Europe since WWII became the primary concerns of the commentariat, we also have had other things to focus on? Maybe our attention is somewhat capricious and not meritocratic? (Did we talk about Climate Change much? Does that mean it's no longer happening?)

Workers getting some more non-real-inflation adjusted hand-to-mouth wages is not a real case of "inequality decreased". Especially with all kind of accounting tricks to hide the real situation on the ground.

This sort of "drop of inequality" is like someone like Musk makes 500 million on a bullish stock market rumor and losses 500 million in a falling market - in a day. Did their wealth and standing in society actually change in any relevant way?

The actual wealth inequality remaining is huge, greater than any time in US history, and still there. Not to mention that this "reversal" comes after a period of unprecedented profits...

Even if a two-billion-aire becomes a mere single-billion-aire because of the stock market, they're still above any imaginable economic related hardship, economically sorted out for 10 generations of progeny, with dozens of ultra expensive tangible assets all around the world, with diversified portfolio and property investments, with huge influence on society and politics, and with tens of thousands of people under their direct control (as employee, owner, etc.).

If on the other hand a 50K a year worker gets to 35K a year (or gets unemployed for a while, or has some medical issue or such), they have to severely downsize their life, their kids education, give up the mortgaged house and rent, or even become homeless, even dead because of lack of medical coverage, the hardship might break their family, end them depressed, and worse. Not some theoritical point: happens to millions every year. Most Americans can't even afford to have a spare $1000 for an emergency.