This morning I noticed that the New York Times blamed rising imports for the fall in U.S. GDP in the first quarter of 2022:

The ballooning trade deficit, meanwhile, took more than three percentage points away from G.D.P. growth in the first quarter. Imports, which are subtracted from gross domestic product because they are produced abroad, have soared in recent months as U.S. consumers have kept spending. But exports, which add to G.D.P., have lagged in part because of weaker economic growth abroad. (emphasis mine)

The part in bold is not right. In fact, it’s the most common mistake in economics journalism. And it’s a mistake that helped to fuel Donald Trump’s misguided trade policies.

Now, most of what the NYT wrote in the paragraph above is correct. It’s certainly true that exports are counted in GDP. And it’s certainly true that slowing export growth reduces the rate of GDP growth. And it’s true that export growth slowed in the first quarter:

But the part of the article I highlighted in bold — the idea that imports are subtracted from GDP — is not right. Imports are not subtracted from GDP. Bloomberg made the exact same mistake, and I heard that NPR made the same mistake as well, as did the WSJ. Even some economists make this mistake. Even the Bureau of Economic Analysis makes this mistake in some of its press releases! So I don’t want to single out the NYT here.

Instead, what I want to do is to explain why imports don’t subtract from GDP. But first, I have to explain why people think imports are subtracted.

Why many people think imports are subtracted from GDP

The way we usually count the components of GDP is by splitting it into the following four parts:

GDP = Consumption + Investment + Government spending + Net Exports

Net exports are just equal to exports minus imports, so you can also write this as:

GDP = Consumption + Investment + Government spending + Exports - Imports

As you can see, in this equation, imports look like they are subtracted from GDP. But in fact they’re not. Because the other parts of GDP — consumption, investment, and government spending — contain more than meets the eye!

Why imports are NOT actually subtracted from GDP

To understand why imports are not actually subtracted from GDP, we first should understand what “GDP” means. GDP is the total value of all the stuff produced within a country’s borders. That’s what the “DP” stands for — “domestic product”. Imports are not produced within the country’s borders, so they don’t count in GDP one way or another.

So how does that square with the equation we wrote above? The key is to understand that imports are also included in consumption, investment, and government spending. The real GDP breakdown looks like this:

GDP = Domestically produced consumption + Imported consumption + Domestically produced investment + Imported investment + Government spending on domestically produced stuff + Government spending on imported stuff + Exports - Imports

So you can see that while imports are subtracted from GDP at the end of this equation, they’re also added to the earlier parts of the equation. In other words, imports are first added to GDP and then subtracted out again. So the total contribution of imports on GDP is zero.

So another way you can write the equation is

GDP = Domestically produced consumption + Domestically produced investment + Government spending on domestically produced stuff + Exports

As you can see, there’s just no imports in this equation at all. Nada. Zilch. Zero.

So why don’t we write it that way? Why do we first add imports in and then subtract them out again?

The answer is that it’s inconvenient. It means that we have to keep track of where each piece of consumption, investment, etc. comes from. And that is hard. It’s much easier to simply measure consumption, investment, and government spending directly, and then subtract out imports at the end to make sure they don’t get counted in GDP. But this easy data collection method leads to popular misunderstandings.

(Side note: There’s also the question of how imports of intermediate inputs are counted in GDP. The answer is that they are also not counted, but the reason they’re not counted is subtler and harder to understand. The St. Louis Fed has a good primer on this. Basically, the reason is that GDP measures only the domestic value added.)

So while it’s very easy for econ journalists to just read off the components of GDP, doing this ignores the fact that imports are also a positive (but hidden) component of consumption, investment, and government spending.

The moon base example

If you still don’t believe me, David S. Chang has a simple example to help explain how this works:

So, this is a very lazy moon base — they’re not doing any science, they’re just importing stuff from Earth and consuming it. But it makes for a good example.

Here’s the GDP equation for the moon base:

Moon base GDP = Consumption + Investment + Government spending + Exports - Imports = $420 + $0 + $0 + $0 - $420 = $0

The moon base’s net exports are -$420, meaning it has a trade deficit of $420.

So now suppose that the moon base’s imports from Earth rise to $690, but nothing else changes. Now we have:

Moon base GDP = Consumption + Investment + Government spending + Exports - Imports = $690 + $0 + $0 + $0 - $690 = $0

Imports went up. The trade deficit went up. But GDP did not change at all! This example shows why economics writers should not write that imports subtract from GDP.

(Anyway, if you still don’t believe me about all this, you can read this explainer by the St. Louis Fed, or this one by Scott Lincicome and Daniel Griswold.)

What if Americans buy imports INSTEAD of domestically produced goods?

In fact, there’s yet another reason a lot of people get confused about imports and GDP. A lot of people are thinking about the situation where American consumers switch from buying domestically produced stuff to buying foreign-produced stuff.

In this case, GDP really does go down, because less stuff is getting produced domestically. Colloquially, we say that “domestic production went down because imports went up”. But what really happened is that consumers simply switched what they wanted to buy. And that ended up increasing imports at the same time that it decreased GDP.

(Side note: This is also true for the case when there’s an increase in the cost of intermediate inputs, though again it’s a lot more subtle. If the cost of imported intermediate inputs goes up, and domestic producers can’t pass on those costs to buyers, then imports will go up and GDP will go down, because the domestic producers are simply adding less value to the inputs they buy.)

Now if this kind of thing happens a lot, then you would see a correlation in the data between increased imports and falling growth. But in fact, when we look at the data, we see the opposite correlation. GDP growth tends to be faster when imports go up!

Now, you could say “OK, but if we hadn’t spent that money on imports, and had spent it on domestically produced stuff instead, growth would have been even faster.” And for some things that’s probably true, but for some things it isn’t true. For example, if the government forced American car producers to use more expensive American steel and less cheap European steel, U.S. steel producers would enjoy a boom, but this would probably be outweighed by the reduced output of American car companies. Imported inputs would fall, but GDP would also fall. In fact, this is what happened as a result of Trump’s steel tariffs.

Imagine if we were to simply ban all international trade. Our trade deficit would vanish. But do you think GDP would go up? I guarantee you the opposite would happen.

In general, it’s a lot easier to answer questions of “How do things add up?” then to answer questions of “If we hadn’t done X, what would we have done instead?”. The former is just accounting, while the latter requires a deep understanding of the workings of the economy. For example, the time I spend petting my rabbits, like imports, is not counted in GDP. If I hadn’t spent that time petting my rabbits, would I have spent the time producing economically valuable goods and services? Maybe. But maybe I would have just watched Netflix. It’s hard to know.

So even if they’re trying to think about the cause of GDP growth rather than just the accounting components, econ journalists shouldn’t write “Imports subtracted from GDP”. Because it’s simply very hard to know whether the economic forces that caused the increase in imports were good, bad, or neutral for the economy. And we certainly don’t know the dollar amount.

In fact, in the case of Q12022, some piece of the import increase probably did come from Chinese lockdowns and energy and food disruptions from the Ukraine war. And those things also tend to reduce GDP. But we don’t know how much this effect contributed. And some piece of the import increase came from consumer spending; if consumers had instead retrenched and started stuffing their money under their mattresses, imports would have gone down, but GDP also would have suffered.

In other words, even though there are some things that increase imports while reducing GDP, you can’t just say “Imports went up by $50 billion so GDP went down by $50 billion”. That’s just not correct.

Why this matters

If this were just a technicality, I wouldn’t care. But I’ve spent years trying to debunk this mistake, because it was the foundation for Trump’s trade policy. Trump’s economic advisor, Peter Navarro, believed that it was possible to pump up U.S. GDP by restricting imports. That was an important part of the way Trump sold his trade policies. It was an argument repeated to me in conversations with right-wingers and Trump supporters throughout the administration.

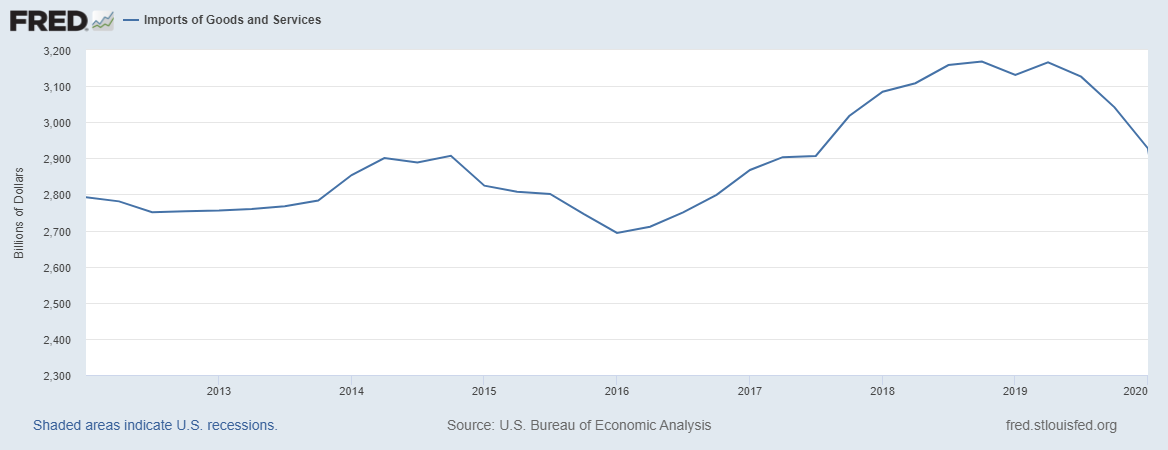

It didn’t work. Sure, growth was strong during Trump’s tenure in office. But imports also rose for most of that time:

And the tariffs almost certainly hurt U.S. GDP a bit. For example, Lake & Liu (2021) look at an earlier round of similar steel tariffs under George W. Bush, and find:

Our results show that, at best, the [Bush] tariffs only slightly boosted local employment in steel-producing industries. But, the tariffs substantially depressed local employment in steel-consuming industries and this depression did not bounce back after Bush removed the tariffs. These results suggest significant and long-lasting damage from the Trump administration’s national security tariffs on steel and aluminum.

Now that doesn’t mean trade wars are always bad — maybe you’re willing to hurt the U.S. economy a little if it means you can hurt the Chinese economy by even more. That’s a choice for politicians, and the nation, to make. But the idea that simply curbing imports will mechanically raise GDP was simply false. And remember that Trump’s tariffs were leveled not just against China but against key U.S. allies — Europe, Canada, Japan, etc. Pretty much any way you slice it, that was a loss.

So that’s why I want econ journalists to stop saying that imports “subtract from GDP”. Not only is it not true in the accounting sense, and usually not true in any deeper causal sense, but it leads to the kind of thinking that encourages harmful approaches to trade policy. I’m not just being an annoying pedant here. This stuff matters.

Can we list and address other common econ journalism fallacies? Like the idea that the strength of a country’s currency represents how strong their economy is?

This is a great post. Such a clear explanation not only of how imports don't count in GDP but why it matters that people are getting it wrong. Thanks for writing this.