If this is a bad economy, please tell me what a good economy would look like

We should acknowledge that things are going well, even as we continue to look for problems to solve.

(Housekeeping note: The Substack comments phishing problem seems to have been at least temporarily solved, so I’m going to try opening up comments to everyone again.)

I do not want to be a shill for the Biden administration. Yes, I like most of what Biden is doing on industrial policy. But I really want to resist being one of those center-left pundits who always just blasts out the latest press release of a Democratic administration and trumpets how many jobs the President has “created”. That sort of partisan cheerleading would be damaging to my credibility (or at least my self-respect) as an independent analyst of the economy, and it would also play into the kind of silly simplifications that the media too often uses to talk about the macroeconomy — for example, the idea that the President “creates jobs”, or is responsible for everything that happens to the economy under his watch.

And yet when I look at how the U.S. economy is doing right now, I find it difficult to describe it in terms that allow me to avoid sounding like a shill. I know lots of Americans still think the economy is doing poorly, and are upset about that. But when I look at objective measures, I just can’t rationalize that negative viewpoint. Because as far as I can tell from the actual numbers, this economy is doing really, really well.

Why the economy is doing really, really well

What do we want from the macroeconomy?

We want employment to be high, meaning that as many people as possible who want jobs can get them.

We want inflation to be low, so that people have certainty about how far their paycheck and their savings will go in the future.

We want real incomes to rise, meaning that we’re able to consume more than we could in the past, or save more if we want to.

(There’s a fourth thing we might want, which is wealth, but that’s more complicated and I’ll talk about it later.)

Basically, this is the whole list. If people have jobs, inflation is low, and real incomes are rising, the economy is good. That doesn’t mean people necessarily realize it’s good — social strife, or partisan polarization, or lingering pessimism from past disasters may cause people to be pessimistic about the economy even in the face of great data, a phenomenon some refer to as a “vibecession”. But while I acknowledge that people’s feelings are important and that there are other things that matter besides the economy, when I’m analyzing how well the macroeconomy is actually performing, I can’t go on vibes.

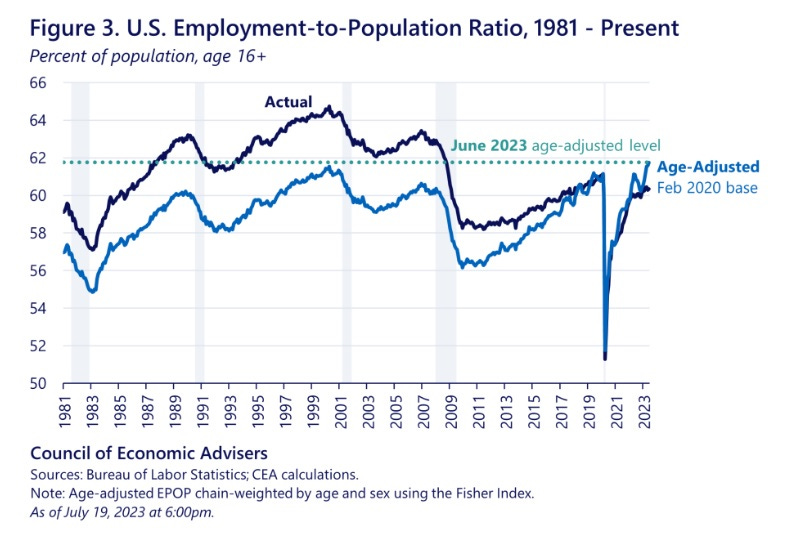

And when we look at the objective numbers, they are great. First of all, there’s the employment situation. Some indicators of employment, like labor-force participation, look bad because we’re in the middle of the great Baby Boom retirement. That’s why you generally shouldn’t use measures of the labor force that don’t adjust for age! When we do adjust for age, we find that the U.S. job market is now the best that it’s been in recorded history. Here’s the employment rate — i.e. the percentage of Americans who have a job — adjusted for age:

This shows what the employment rate would have been since 1981 if the fractions of the U.S. population in each age group were the same as in February 2020, right before the pandemic. Basically, we have a much older population today than we used to, and this is a way to try to take that into account. Now you can say “Well, if the labor market of 2023 were as good as 1999, then old people would be working a lot more in 2023 than they did back in 1999.” And maybe that’s true, but if so, there’s not really much way to tell. The assumption that aging works about the same in 2023 as it worked in 1999 seems like a good one. And even if the reality is a little bit off from that assumption, we’re still pretty damn near the best labor market ever.

Next up we have inflation. This has, of course, been the big problem since the start of 2021. But now inflation is plunging; if it’s not back to its target, it’s headed there very rapidly. In month-to-month terms, PCE inflation (which the Fed likes better than the more commonly used CPI) is now below the 2% target.

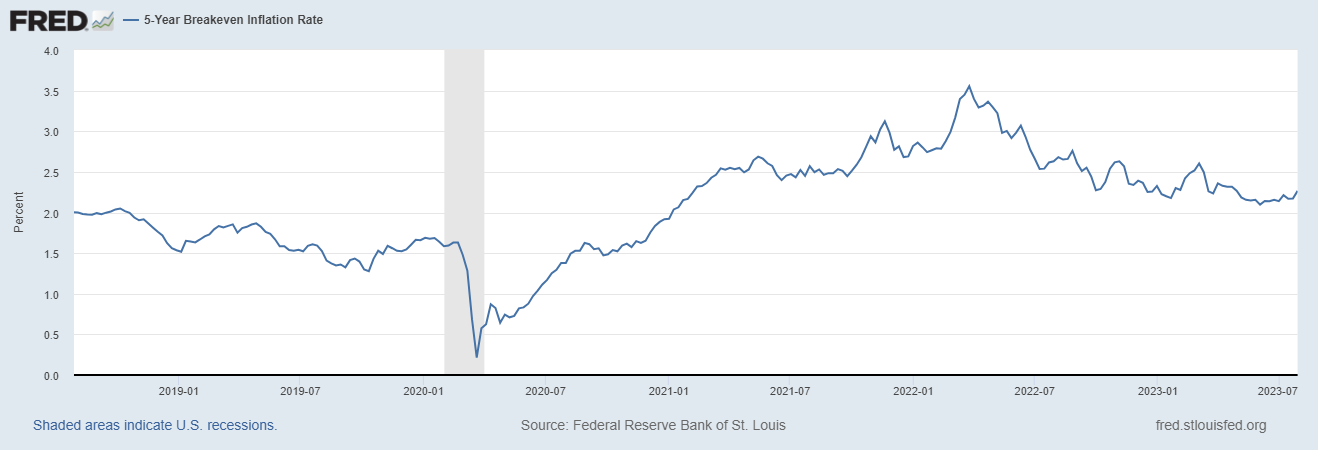

Slower-moving measures are all headed downward. Broader measures are falling rapidly as well. And when you include the rents that people are paying on new leases instead of rents for leases signed long ago, inflation looks even lower. Meanwhile, market inflation expectations, measured by the 5-year breakeven, increasingly look like they’ve been completely tamed, which means people think the Fed has inflation under control in the long term:

I don’t want to say that we have inflation completely beat. First of all, circumstances could change — oil prices could spike again, as they are known to do, or chaos somewhere in the global supply chain could cause a repeat of early 2021. And I expect the Fed to keep rates high until they’re absolutely sure the post-pandemic inflation is over, which might be a year or two. But whatever part of inflation the government was causing by pushing up excess demand looks like it’s now gone.

And together, the strong labor market and slowing inflation are delivering the third thing we want the macroeconomy to deliver: real income growth. Real GDP grew at 2.4% in the second quarter, which is a decent clip for an aging developed country, and represents a return to the pre-pandemic trend. (Remember that GDP is really just a measure of aggregate income.) But the Atlanta Fed’s growth forecast for the third quarter — or “nowcast”, as they call it, since we are in the third quarter now — is 3.5%. That’s pretty darn good!

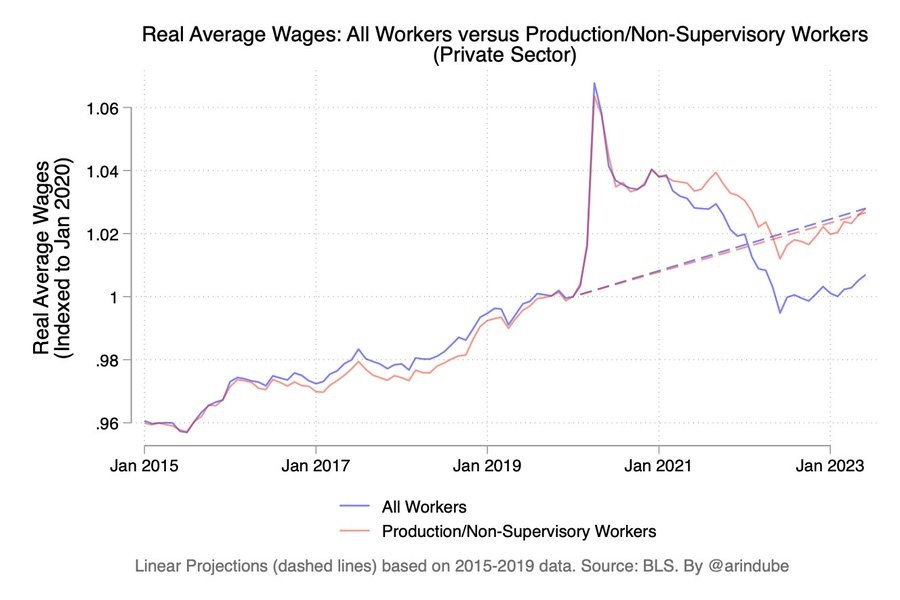

And in case you’re wondering whether most of that income growth is flowing to the rich, well, let’s take a look at wage growth. Real wages fell during 2021 and the first half of 2022, but when inflation came down, they started rising again. Now, labor economist Arin Dube reckons that wages for production and supervisory workers — i.e., regular workers — are all the way back to their pre-Covid trend line:

Now, that trend line looks a tiny bit suspicious to me; I think it should be a little bit steeper. But it’s pretty clear that things have really turned around for the average American’s wages since mid-2022. And when Dube adjusts for aging, he finds that the wage picture looks even better:

In fact, a whole lot of other indicators of material prosperity are looking really good these days. I could list a bunch, but I won’t; they pretty much just track wages and employment, with small differences. One of my favorite statistics, though, is that Americans’ consumption of physical goods is all the way back to its trend line from before the financial crisis of 2008!

This economy isn’t just good; it’s impressive

Anyway, this is all very good news. But I want to point out how improbable and surprising it is, from a macroeconomic standpoint. The basic theory of macroeconomics — still, in this day and age — includes the idea of the Phillips Curve. That means that when the government takes action to reduce inflation — raising interest rates, cutting deficits, etc. — it’s supposed to reduce real income growth and employment. There’s supposed to be a tradeoff there!

And yet instead there seems to have been no tradeoff at all. OK, maybe the Fed’s rate hikes just haven’t had time to work their way through the system yet — maybe 1.5 years isn’t enough. Maybe we’ll still eventually get that recession that everyone was forecasting up until a short while ago. But so far it looks like we’ve managed a macroeconomic miracle — bringing inflation down without damaging the real economy noticeably.

One way to see how unusual this is is something called the “misery index”. In the 1970s, the economist Arthur Okun created this number to measure the stagflation that was happening at the time. It was just the sum of the unemployment rate and the yearly inflation rate — nothing special, nothing from deep economic theory, just adding up the two things Americans were unhappy about. Here’s how the misery index has looked since it was invented:

Rises in this number basically indicate a worse tradeoff between inflation and unemployment. So the fact that we’re now headed toward all-time lows means that we’re approaching the optimum tradeoff.

But just for fun, let’s construct an alternative “misery index”. Instead of the unemployment rate and inflation, let’s take the deviation of the prime-age employment rate from its historical maximum, and then subtract real wage growth. Basically, that’s a better measure of labor market failure and a better measure of the erosion of real purchasing power. If we do that, we see that the current economy is the least miserable since at least the mid-2000s, and maybe since the late 90s:

And since this is year-over-year inflation, assuming inflation continues on its downward trajectory without a sudden recession, these numbers are all going to look even better in a few months.

This is a remarkable achievement. Who gets the credit? Because we don’t really know how macroeconomics works, we can’t actually give a definitive answer to this. Some of it was probably luck. Russia ended up having to sell a lot of oil at cut-rate prices to fund its war effort, which helped bring global oil prices crashing down, which boosted the real economy and helped stop inflation. China’s economic mistakes and burst real estate bubble tamped down global demand for commodities and helped restrain inflation even more, while not really reducing demand for U.S. goods much (since China doesn’t import much from the U.S.). And of course the U.S. economy is just an inherently resilient machine that tends to bounce back from recessions.

But there’s a good argument for U.S. policy doing a lot here too. We’ll probably never know just how much the Fed’s rate hikes were responsible for taming inflation, but to think that rates can go from 0% to 5.5% with no effect would be quite an assumption. The fact that this didn’t also cause a big increase in unemployment (yet) represents a stroke of luck; macroeconomists were prepared for a much more costly disinflation, and those costs didn’t end up materializing. People will be arguing for a long time about why we got so lucky there. But I think it’s pretty plausible that rate hikes did help tamp down inflation.

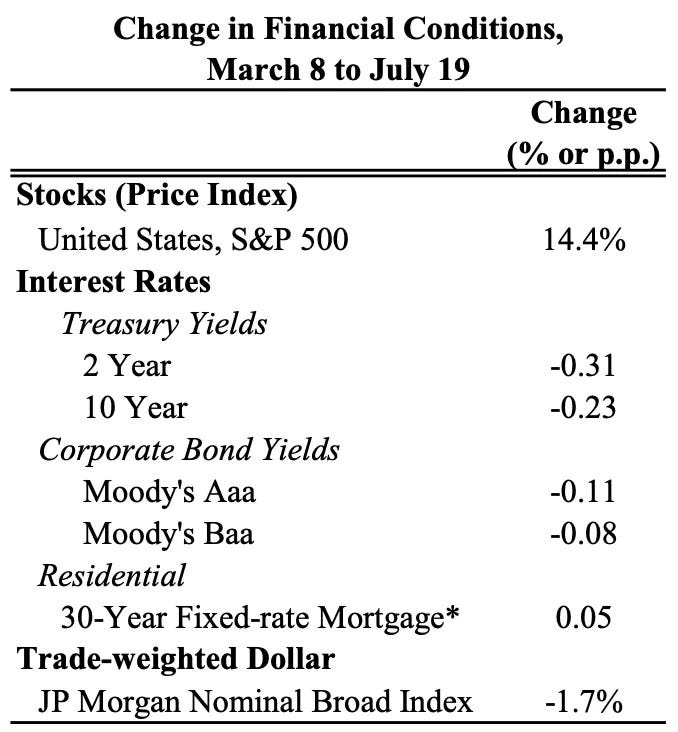

There’s also the financial side of things. Remember that a large-scale collapse of financial institutions very reliably causes economic downturns — 2008 being the most dramatic example. This could have happened in the U.S. banking system last year — rate hikes put a lot of banks in danger, and a few mid-sized regional banks like Silicon Valley Bank actually failed. But the FDIC, the Fed, and the Treasury stepped in and guaranteed bank deposits and provided emergency loans, and the banking crisis that lots of people were predicting never materialized. In fact, financial conditions in the U.S. actually improved after SVB’s collapse!

In addition, the Biden administration might have had something to do with low oil prices. Biden released a bunch of oil from the strategic petroleum reserve back in 2022, and teamed up with Europe to put a price cap on Western purchases of Russian oil that may have allowed China and India to negotiate lower prices as well. Biden also mended fences with Venezuela and encouraged U.S. companies to start investing there again, which is starting to bring that country’s production back on line after a long hiatus. Remember that a drop in oil prices is a positive supply shock, which economic theory says should boost growth while also reducing inflation — i.e., exactly what we’ve seen over the last year or so.

And finally, there’s the investment boom. The CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act are spurring a ton of private investment in semiconductors and green energy:

The Biden administration claims that this contributed about 0.4 percentage points of the 2.4% GDP growth in the second quarter, which is a pretty robust contribution. Of course, that’s just mechanically adding up dollars; we don’t know for sure how much other economic activity that subsidy-induced factory boom caused or prevented. And you can say that this is all wasteful investment that won’t create economic activity in the long term. But still, it seems fairly likely that this is making a positive impact right now. Morgan Stanley and other banks think it’s having a major impact, in any case.

So although I always stress that the President has a limited impact on the economy, there are several reasons — oil policy, bank rescues, and industrial policy — that I feel inclined to give Biden some credit for the economy’s surprisingly stellar performance. Not all, but some.

Steelmanning the case for a bad economy

OK, but remember, I don’t want to be a Biden shill. If people feel like the economy is actually in the dumps, despite all this positive data, I care about that — and I want to know why. Consumer sentiment is still near its all-time lows:

So let’s “steelman” the case against this economy. What are the strongest arguments for why it’s actually not doing well?

Well, one possible reason is that although wages for the average worker are back to trend, disposable income is not:

What we’re seeing here is the “richcession” — incomes in the upper part of the distribution fell a lot more than incomes at the bottom and middle, and have recovered less. This is bound to make the upper middle class quite grumpy, so they might be giving very negative answers on consumer confidence surveys.

Also, Americans of all classes probably haven’t forgotten the way that their incomes and wages fell for a year and a half. That was an unusual, traumatizing experience, and it may take some time for people to realize that that episode is behind them.

Finally, there’s one other thing that people expect from the economy, which I didn’t discuss earlier: wealth. Wealth conveys a sense of security above and beyond what income can provide, especially for older workers who don’t have many working years left. And since the beginning of 2022, real wealth has been going down for the American middle class:

The drop is partly due to inflation, which reduces the value of most bonds. That is now easing, but the value of those bonds will not bounce back to what it was.

Meanwhile, much of the ongoing wealth decrease is due to another factor. Home prices — which comprise the majority of the wealth of the American middle class — have been falling.

Home prices have been going down because of interest rate hikes. Rate hikes make mortgages more expensive — mortgage rates are now almost at 7%, higher than they’ve been since before the financial crisis. That makes it harder to buy a house, which reduces demand for houses, which reduces the market price.

Thus, middle-class Americans just saw their bond wealth erode from inflation, and now they’re seeing their housing wealth erode due to the methods we deployed to fight inflation. Nobody likes feeling poorer.

Now, macroeconomists don’t necessarily think that the macroeconomy exists to raise the value of people’s bonds and houses. To a macroeconomist, the value of the economy is just its GDP, and wealth is just an accounting method that people use to divide up who gets what. But in the real world, wealth is a very important part of whether people feel like they’re thriving or struggling.

So there’s the “steelman” case for why the average American might still feel grumpy about this amazing macroeconomy. It’s a combination of:

the traumatizing impact of a year and a half of falling wages,

upper-middle-class real wages and incomes that haven’t fully recovered from inflation, and

reduced middle-class wealth due to inflation and (especially) rate hikes.

That’s not the strongest case I’ve ever heard, but it’s not ridiculous either. In any case, it’s just me taking my best guess; if you can think of any other way in which this economy could be better, please let me know.

So if my guess is right, what do we do about it? Concerning the first two of those problems, the only thing to really do is wait, and let the post-pandemic inflation fade into the rearview mirror, and let wages and incomes continue to recover. But as for the third point, house prices will only go back up once rates come down. So we may have to wait for rate cuts in order for Biden & co. to be able to convince the public that it’s really “morning in America” again.

Agree with your comments.

One area where we're not doing well and it's causing real pain is home/apt building. No one could credibly disagree with the observation that we have a real housing crisis. Yet that's exactly where the current economy is coming up most short. Home builder's can't build (because they can't sell) in volume. And apartment construction has fallen off a cliff owing to the doubling of debt costs combined with equity having run to the sidelines (I'm a large scale apartment developer.)

So just when we need a large supply boost, and the YIMBY movement is making real headway on the entitlements front, the factors required for a big housing supply increase have run into a head wall in the form of the current economy.

I think this misses an important point, which is that while INFLATION has gone down, PRICES haven't. Now, I know: inflation going down doesn't mean prices go down. Prices going down would be DEFLATION, and that's bad. Yes yes yes. But most people don't get this. For most people, inflation means "My groceries cost 15% more than they did two years ago!" And groceries still cost 15% more than they did two years ago. So inflation hasn't gone away. Again, I'm not endorsing that thought process, I'm just saying it's very common.