Ideas to boost Japanese growth (Part 1)

Let's get this party started.

Greetings from Tokyo! This is the second in my series of Japan-related posts. The first one was about how Japanese living standards are too low. I recommended that Japan address its high poverty rate by creating a cash-based redistributive welfare state, on top of the creaky, failing corporate welfare state that it has traditionally relied on.

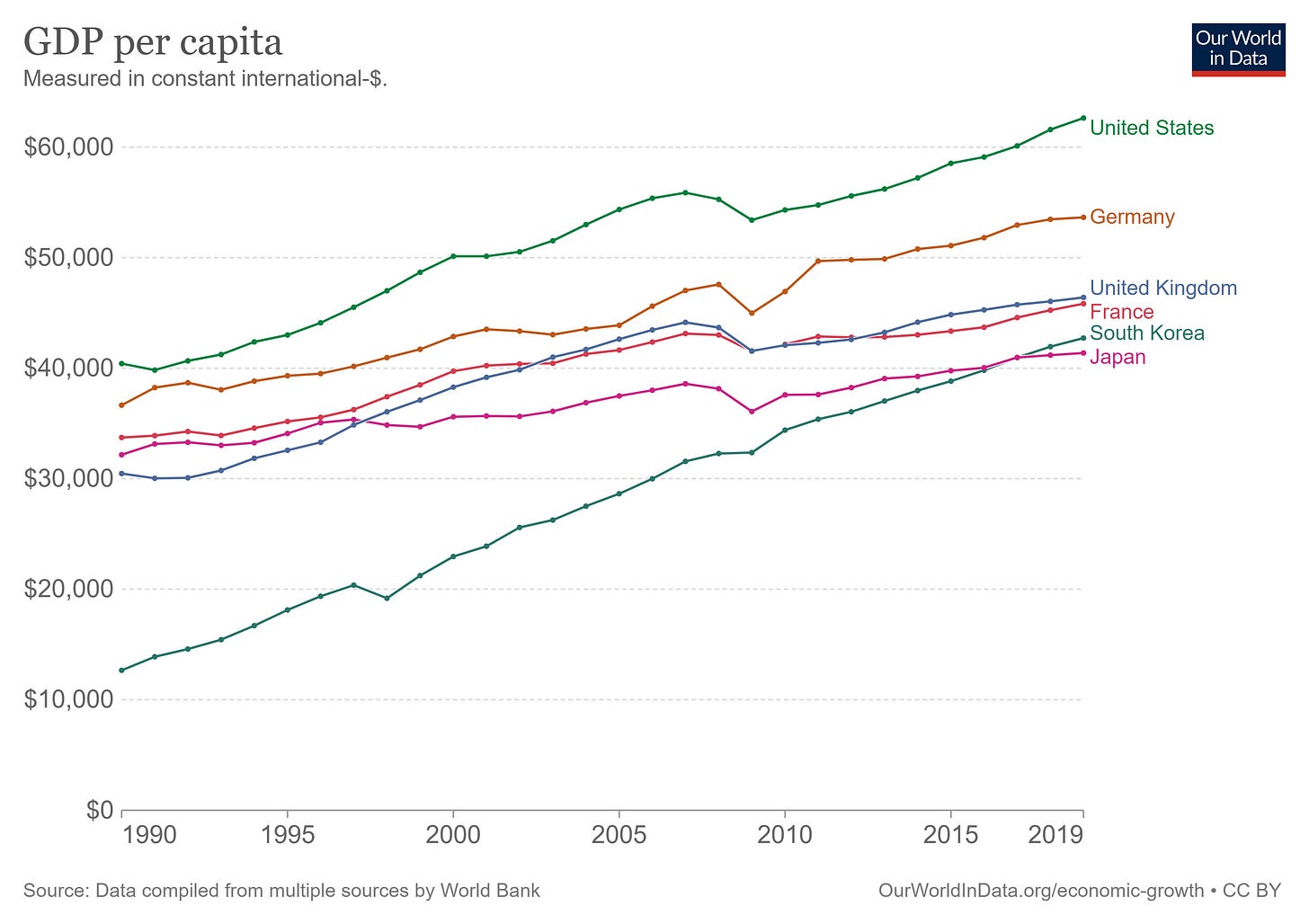

But redistribution isn’t going to be enough to give Japanese people the kind of material welfare they deserve. The three decades of slow growth since 1990 have left Japan in the lower rank of developed countries, in terms of overall GDP:

Low-ish per capita GDP means there are just fewer resources to redistribute. That’s why growth acceleration has to be a big part of any boost in Japanese living standards.

Growth policy is hard, especially for rich countries that are close to the technological frontier. Basically, there are two problems holding Japan back in terms of GDP per capita:

An aged (and aging) population

Low productivity, especially outside of manufacturing

Aging affects per capita GDP pretty mechanically — the more retired people you have, the less people you have who produce stuff. Japanese people have been postponing retirement more and more, but there’s a limit to this. The only ways to solve the aging problem are immigration and higher birth rates, and encouraging higher birth rates is hard (Japan’s are already higher than other countries in East Asia). I’ll discuss immigration in a bit.

Productivity is probably easier to improve, though “easier” doesn’t mean “easy”. Japan is famous for its low office productivity. Here’s a good quick primer from Morikawa Masayuki, president of the think tank RIETI. Key graph:

And this chart probably understates the problem, since Japanese workers are known to put in lots of unpaid overtime, which means true per-hour labor productivity is even lower.

The woes of the Japanese workplace are by now well-known. Workers spend long hours sitting around in open-plan offices trying to look busy for the boss, waiting for the boss to go home. Young workers are paid near-poverty wages even at good companies, with raises dependent entirely on seniority rather than performance or value-added. Promotions are also seniority-based, meaning management is stuffed with old guys who don’t understand the benefits of new technologies, new markets, and new business models. This model also stifles the contributions of women, immigrants, etc. And by preventing employees from moving from company to company, it keeps ideas and knowledge from flowing and recombining.

Fixing that broken corporate culture is an important part of the story of low Japanese GDP, and I’ll talk about ways to address it. But it’s only part of the puzzle. In today’s post, I want to list some steps I think Japan can take to boost growth above and beyond corporate culture reform. I’ll cover culture in a follow-up post.

1. Export more

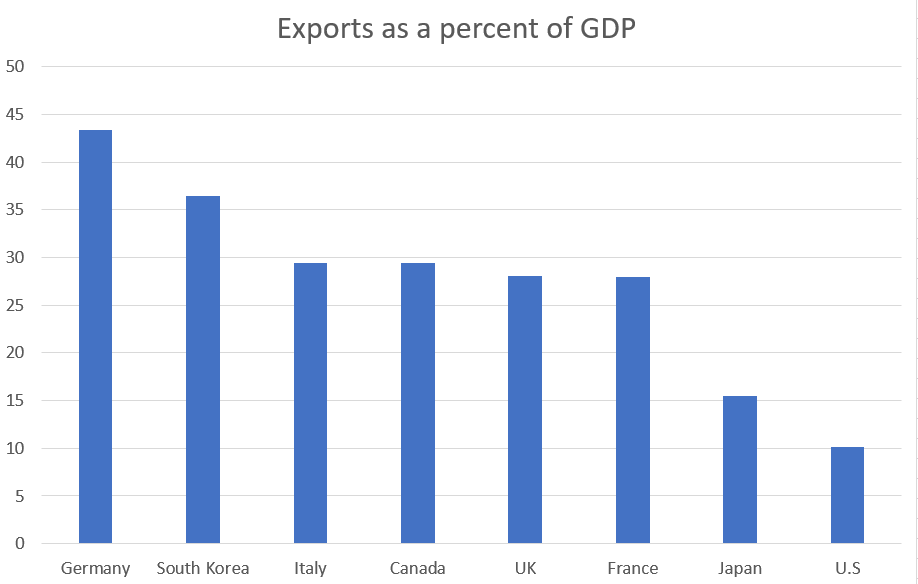

Lots of people think of Japan as an export powerhouse. When you hear about “export-led growth”, you often hear Japan’s name mentioned in the same breath. So it might surprise people to learn that Japan’s economy actually doesn’t export very much, relative to most of its rich-world peers:

Nor is this a recent development:

Part of this is that Japan has a big economy, and big economies tend to export less than small ones (relative to GDP). Part of it is that Japan isn’t in Europe, so there aren’t a lot of other rich economies nearby with free trade policies, ready to consume its products. But part of it is that Japanese companies tend to be insular by nature, focusing on the home market instead of venturing out.

This needs to change. Exporting is important because when your country is shrinking demographically, overseas markets represent the best (and often the only) opportunity for expansion. There are also other benefits of exporting — raising productivity by learning foreign ideas and competing in world markets, etc. — but really the most important thing is just market size.

(And it’s important to note that the benefit of exporting has little to do with trade surpluses; the export revenue can and should be used to import more foreign goods, which raises domestic consumption!)

So Japan needs to focus on exporting more. A good initial goal would be to raise exports from 15% of GDP to 20% of GDP.

Part of this is to sign more trade agreements, which in fact the country has been doing a lot of. But more vigorous export promotion efforts are needed. The country’s trade bureaucracy, METI (formerly MITI) needs to revive its practice of actively pushing Japanese companies to sell overseas. The Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) will be key for this, and it will probably be necessary to bring in some new blood to the top levels of that organization.

A big part of this will involve teaching Japanese companies that they need to sell overseas directly (and helping them learn how to do this). Traditionally, Japanese exporters relied on intermediaries called sogo shosha to sell their products for them, but these middlemen have become redundant and cumbersome in the age of the internet, and have basically morphed into investment banks. More Japanese companies need to learn a culture of marketing overseas, acquiring overseas companies as beachheads, building overseas branches staffed with local talent, and so on. No more relying on sogo shosha.

2. Build a globally competitive alternative energy industry

Energy is a key factor of production. It affects manufacturing costs, but also costs for service businesses, which need to keep the lights on. So ensuring abundant energy supplies is key.

Japan’s electricity prices are moderately high, though not as high as in some European countries. To make matters worse, Japan has few fossil fuel resources of its own, meaning that it doesn’t get much of a GDP boost from domestic energy production (as the U.S. gets). Instead, it imports most of its fuel from abroad.

One way Japan has traditionally gotten around this is nuclear power, whose fuel costs are low as a percent of overall costs. But ever since the 2011 tsunami and Fukushima nuclear disaster, there has been a vigorous popular movement against the use of nuclear power. Japan’s lawmakers have been quietly restarting reactors, but it has been slow going, and is likely to remain slow going.

Fortunately, technology has changed the game in terms of energy, in ways that Japan is well-positioned to take advantage of. The populated southern regions of Japan are fairly sunny, matching Southeast Asia or South Europe for solar potential:

Whereas the north of Japan matches North Europe for wind power potential:

Japan also has a fair amount of geothermal potential.

Japan lacks land, of course — it has about the same land area as California but four times the population. Building solar and wind energy will require some offshore construction, which will raise costs. But Japan is a technological leader in this area, and promoting the development of the offshore renewables industry (by having the government buy a lot) will help Japan become a technological leader in this area, which will give Japanese companies the chance for more high-tech exports. So there’s that. McKinsey recommended this in a 2020 report.

Japan should also promote the development of hydrogen as a storage medium. With solar modules already dirt-cheap and grid penetration increasing, intermittency is emerging as the main barrier to solar. As David Roberts informed me in a recent interview, electrolysis is emerging as the most promising long-term storage medium, to smooth out solar (and wind) across the days and months. Japan, oddly, has an advantage in hydrogen technology after a failed bet on hydrogen cars. Hydrogen turned out not to be as good as batteries for cars, but for long-term energy storage, it has a good chance to be the winning technology. So Japan’s government should encourage hydrogen energy storage, and take advantage of those learning curves to build a dominant position in what’s likely to be an important global industry.

3. Create a defense-research-industrial complex

Japan spends a decent amount of its GDP on research and development — more than the U.S. as a percentage of GDP. But this probably isn’t being spent in the most efficient way. Much of this spending is done by Japanese companies in corporate labs, which is fine, but is more likely to be narrow-bore applied stuff and less likely to be groundbreaking basic research that propels dominance in whole technological fields.

The U.S. also has this problem. But what the U.S. has, and Japan lacks, is a robust defense research ecosystem. The U.S. actually funds a huge amount of stuff through defense spending:

Part of this is peculiar to the political economy of the U.S., where lawmakers are more eager to approve defense spending than other spending. But it probably also comes with collateral benefits — DARPA, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, is responsible for a startlingly large number of foundational innovations, including the internet and GPS.

Japan needs its own DARPA. The threat of a war with China over Taiwan has motivated Japan’s leaders to pledge increased defense spending (the country’s post-WW2 era of pacifism is over). A significant fraction of this should be devoted to developing cutting-edge technology, whose uses will inevitably spill over into the private sector.

4. Increase late-stage funding for new companies

Japan’s top companies — Toyota, Sony, Nintendo, etc. — tend to be pretty old. There are few equivalents of, say, Google or Amazon. Even Japan’s most dynamic big companies — Softbank, Fast Retailing, Nitto Denko, etc. — tend to have been founded before 1990.

But this wasn’t always the case — the early and mid 20th century saw a burst of entrepreneurship. You can read about this history in the book We Were Burning, by Bob Johnstone. Economic growth, exporting, and innovation would all get a boost from returning to an era of entrepreneurship.

In recent decades, Japan has made some strides in improving funding and support for startups:

But as any number of reports and blog posts will be happy to explain to you, Japan really suffers when it comes to late-stage financing. Japanese entrepreneurs can start companies fairly easily, but have trouble when it comes to scaling them up into giants. This is one reason Japan has failed to build a world-class software industry, to go alongside its world-class manufacturing industries.

Making more late-stage financing available to Japanese startups thus seems like a logical move. It shouldn’t be too hard to do this with the right combination of tax breaks and regulatory encouragement.

5. Institutionalize the immigration system

Now we come to immigration. Japan has the reputation of being a closed-off country, but this is now a decade out of date. Under former Prime Minister Abe, Japan began to dramatically increase the number of foreign workers in the country:

Just what constitutes “immigration” is a little fuzzy here — some of these workers are Chinese kids on student visas working at convenience stores for a couple years before they go home. But under Abe Japan did create two programs for permanent immigration — a path to citizenship for guest workers, and a fast track to permanent residency for skilled workers.

Much more of that sort of regulated, institutionalized immigration would shore up the labor force more. It will not make up entirely for a lack of domestic births, but it will slow aging until solutions to ultra-low fertility rates can be found. To this end, the government should heavily prioritize young workers and students, as they will reduce the old-age dependency ratio (the number of retirees per worker) by the most.

Of course, ultimately it’s the Japanese people’s choice how much immigration to allow. In the U.S. I am a vocal advocate of higher immigration. But the U.S. is my country, and so I get a say in whether we take in more people; where Japan is concerned, I can point out the economic benefits, but Japanese people themselves must decide whether immigration comes with a cultural cost. The U.S. is fairly unusual in being a country composed mostly of the recent descendants of immigrants, and we Americans should understand that most other countries, including Japan, may define their nationhood and culture differently than we do.

One reason Abe’s immigration policies were done quietly and in piecemeal fashion was fear of a domestic political backlash; it managed to pump up numbers while maintaining the fiction that these were mostly guest workers who would eventually return to their original countries. But guest-worker programs just don’t work as a permanent solution.

But if the Japanese government wants ways to make regular, high-skill immigration more palatable to its people, there are probably ways to do this. One would be to allow prefectures to sponsor immigrants, as Canada does with its Provincial Nominee Program. This would direct immigrants to live in depopulating regions where they’re more likely to be welcomed and less likely to add to urban crowding. A second measure would be to create a modified form of birthright citizenship, so that people born on Japanese soil to permanent residents of Japan are automatically citizens of Japan. A third would be to popularize the linguistic equivalent of “hyphenation” — i.e., the equivalent of “Italian-American” or “German-American”. (In Japanese, this is “-kei Nihonjin”, but the term isn’t yet common.)

Bonus Idea: Create a Japanese Hong Kong

The above ideas are all pretty standard things that the Japanese government already knows about, and has made modest or halting moves toward implementing, but hasn’t really gotten serious yet. So just to round out the list, here’s a big bold idea that I haven’t seen anyone suggest: Create a Japanese version of Hong Kong.

Hong Kong’s existence helped China’s growth quite a lot. It provided a freewheeling, deregulated entrepot where foreign capital could be channeled into China. It helped funnel foreign technology into China. And after it rejoined China in 1997, it provided the government with taxable income.

Fearful of democracy and dissent, China eventually crushed much of what was special and unique out of Hong Kong. But Japan, being a democracy and an open society, would not be fearful enough to do the same to its own equivalent. Thus, Japan should consider creating a special economic zone that functions as a deregulated entrepot for the finance and software industries.

Here’s a sketch of how it would work. Japan would carve out a small area — some lightly inhabited region — to be a special economic zone. It would be organized as a new metropolitan region with its own locally elected metropolitan government, but with special rules set by the central government. Japanese citizens would be free to move to and from this zone whenever they wished. Foreigners who met basic criteria (perhaps similar to those used by Singapore) could very easily become permanent residents of this zone, but moving from the zone to Japan would require an additional visa application. In fact, Japan could encourage refugees from Hong Kong itself to move there.

The Japanese government would invest in high-quality infrastructure within the zone, quickly creating a well-planned, well-functioning city. Within the zone, financial businesses (and other businesses) would be lightly regulated, and foreign capital inflows heavily encouraged. Taxes would be light, trade between the zone and the rest of the world would be essentially unregulated. The zone would have its own free-floating currency, similar to the Hong Kong dollar.

Financial companies set up within the zone would have the ability to invest in Japan proper very easily, while companies set up there would have no barriers to selling in Japan. Japanese banks, while encouraged to invest somewhat in financial companies within the zone, would have their exposure limited, so that inevitable financially driven busts and crises within the zone would not spill over much into the overall Japanese economy.

This zone would do a number of things for Japan. It would allow the country to build a truly global finance industry, and to take over much of the Asian financial entrepot trade. It would function as a channel for foreign capital and technology to enter Japan. And it would create more demand for Japanese exports. In other words, it would be like the Roppongi/Azabu area of Tokyo, but scaled up to city size.

At any rate, it’s an idea worth thinking about. But though this idea is probably too wild and wacky to ever happen, the others on the list are all very feasible and definitely worth doing.

In the third post in my series, I talk about how to fix Japan’s unproductive corporate culture.

Just to provide an on the ground anecdote about Japan's relative lack of exporting...

I live in Vietnam which, for whatever reason, is one of the few places that does seem to attract Japanese exports. And it really drives home how absent they are in other countries (I'm most familiar with Australia and the US).

When I go to a baby store we can choose diapers from Merries, Moony, Genki, and Whito. For formula there's Meiji and Yokogold.

And that's just one tiny example from one store. You wonder why you never see these things anywhere else.

Really well written