How we could return to the productivity growth of the 1990s

A guest post by Preston Mui.

As readers of this blog know, I think productivity growth is extremely important, and I’m hopeful that the “roaring 20s” decade will see productivity accelerate. In the 2010s there was a backlash against the idea of productivity growth, due to worries that wages weren’t keeping up. Those worries turned out to be somewhat overdone. But even more importantly, the return of inflation forced us to remember that rapid productivity growth is what allows the Fed to keep inflation under control without clobbering the real economy with high interest rates. So yes, we need productivity growth.

Just how to get that growth, though, is a more difficult matter. I often talk about supply-side policies like allowing more housing, streamlining regulation to encourage more construction, spending more on research, and encouraging large amounts of high-skilled immigration. Those are all very important, of course. But I’m also interested in the idea that demand stimulus can incentivize companies to invest in productivity improvements. Economists have occasionally played around with this idea, which sometimes goes by the name of Verdoorn’s Law (even though it’s not actually a law).

In fact, I do know someone who advocates for demand-based productivity policy: Preston Mui, a Senior Economist at Employ America, a research and advocacy group dedicated to promoting full employment. So in this guest post, he makes the case.

Is productivity growth back? The last few quarters of data have been encouraging, but it is still too early to be certain. Nonfarm labor productivity—real output per hour—grew at a rate of 2.6% in 2023, substantially above its 2010s average of 1.1%.

What everyone wants to know now is: was 2023 a “one-hit wonder,” or is productivity growth here to stay? The answer to that question touches on every part of the economy; after all, labor productivity growth ensures that increases in living standards and wage growth are sustainable in the long term.

That includes the Fed. For example, take Mary Daly and Austan Goolsbee:

Here’s how I think about [productivity]. I had the benefit of starting at the Fed in the mid-1990s, 1996. And that was right when Chairman Greenspan was looking at all the details trying to figure out if we were having some sort of a productivity boom…. You can miss productivity improvements even when they are happening right in front of you…. I’m optimistic, I’m just not confident that it’s going to happen yet.

— Mary Daly, February 16th, 2024

But in monetary policy specifically, we’ll be back to the 1990s. I mean, this was the—this was the centerpiece discussion for Greenspan in the ’90s, of what are the implications if productivity growth is higher? So I got my fingers crossed that that continues.

— Austan Goolsbee, February 14th, 2024

Daly and Goolsbee are not the only ones making comparisons between today and the 1990s, the last time the US saw strong labor productivity growth. It certainly feels like the 1990s in a lot of ways, and not just because “jeans and a nice top” have come back in fashion. We’ve had a full-employment recovery after a recession, backed by a Fed that is (at least, so far) looking to pull off a soft landing. The excitement over the potential impact of rapidly developing AI technology echoes the beginning of the 1990s tech boom as well.

When debating productivity growth, most focus on long-term trends in demographics or technological innovations. I think those forces are important, but I think the comparison to the 1990s highlights another important factor: the immediate macroeconomic environment plays a significant role in producing higher productivity growth.

While computers are the first thing many think of about productivity and the late 1990s, the late 1990s were also a uniquely good time for the US macroeconomy. After the Fed successfully engineered a soft landing in 1994, the US enjoyed a period of falling unemployment, low inflation, and strong GDP growth. This macroeconomic achievement was so great that Alan Blinder and Janet Yellen termed the 1990s the “Fabulous Decade.”

In this “Fabulous Decade,” three key macroeconomic factors fostered increases in productivity growth: full employment, a boom in fixed investment, and a stable supply-side. While some of these dynamics are present in other expansions, the late 1990s were the only time in recent history with all three.

Each of these three factors is a macroeconomic supporting the stool of productivity growth. Each leg of the three legs supports the other two, and prevents the stool from falling, while providing a sturdy foundation for productivity growth. In the 1990s, the stool was held together both by sensible macroeconomic stewardship and good fortune. Today, building a base for further productivity growth hinges on securing each leg of the stool.

Full employment supports productivity growth

Until the post-COVID recovery, the post-1990 recovery was the last time we saw a full employment recovery after a recession. The unemployment rate, which nearly reached 8% in mid-1992, fell to its pre-recession levels, just above 5%, by 1996. But the labor market recovery didn’t stop there; the unemployment rate continued to steadily fall throughout the late 1990s, eventually even falling below 4% before the 2000 recession. The American labor market hadn’t seen unemployment this low since the 1960s, and wouldn’t see it again until 2022.

OK—but what does that have to do with productivity growth? First, full employment means more than people simply having any job. Tight labor markets mean that workers are able to find opportunities to move to more productive and higher-paying jobs. You can think of employed workers as moving up a ladder of job quality as they switch jobs, unemployment knocks them off that ladder. When unemployment stays lower for longer, as in the 1990s, workers get the chance to climb further up the ladder.

It’s also important that workers are given sufficient time to get trained up in their new jobs. Lags between a worker starting in a new job or occupation and actually producing output might explain why the shape of productivity growth in a period of labor market expansion. Measured productivity growth is generally slow (or even negative) when employment is rapidly recovering from a recession, but it tends to pick up later in the expansion as employment gains slow down.

Full employment economies are also economies that are able to support robust demand growth. As the 1990s economy matured, employment gains slowed down (but were still positive). As employment growth slowed, wage growth picked up. Since income at the macroeconomic level is determined by both employment and wage growth, this dynamic allowed labor income, and thus consumer demand, to continue to grow throughout the decade.

Robust demand growth is crucial to labor productivity growth because it supports the decision of firms to invest. Productivity growth doesn’t just fall from the sky. Rather, it arises from deliberate choices by firms to invest in innovation and technology that improve productivity. One key insight of the “Keynesian Growth” literature is that insufficient demand growth—like we saw in the 2010s—can harm productivity by reducing the incentive for firms to invest, particularly in research and development.

The Stars Align for Fixed Investment

That brings us to the second leg of the stool: investment. One of the defining features of growth in the 1990s was a strong contribution from investment. Between 1995 and 2000, fixed investment reliably contributed between 1.0 and 1.5 percentage points to real GDP growth.

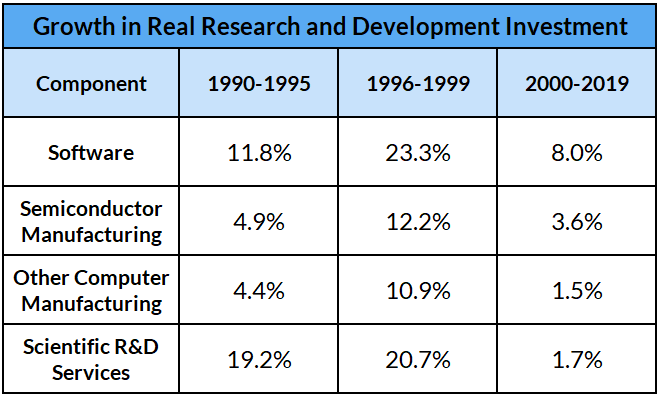

Investment growth was particularly pronounced in areas related to the tech boom during this decade: computer equipment, software, research and development, and telecoms equipment and structures. Growth in research and development in areas related to the computer boom averaged in the double-digits during the late 1990s.

This investment in research and development resulted in tremendous quality improvements in computer technology. The rate of improvement of Intel processors between 1997 and 200 was more than double that of 1984-1997. This rapid improvement in quality meant that real growth in computer investment was primarily due to a de facto decline in the quality-adjusted price of computer equipment over time. The development of computers was so rapid that the Bureau of Labor Statistics had to develop new techniques to account for changes in quality. This meant that the computer sector was able to provide a large contribution to real growth without a commensurate increase in nominal expenditures.

Tech investment also led to productivity improvements elsewhere. Oliner and Sichel (2000) estimate that nearly half of the improvement in labor productivity between the early 1990s and late 1990s is attributable to the investment in computer, software and communications equipment.

Why was there such a boom in fixed investment in the 1990s? I see three stars that aligned to promote investment. The first reason, as I explored earlier, was the presence of strong aggregate demand after the full employment recovery that validated investments in technology.

Second, the federal government played a critical role in coordinating research and development in semiconductors under a “science policy” model. While this policy fell short of the industrial policy seen today with the CHIPS act, science policy in the 1990s focused on coordinating research efforts and setting out a roadmap for product development.

Finally, financial conditions were relatively looser during the 1990s, with real interest rates falling from their higher levels in the 1980s. This was partly due to irrational exuberance in financial markets, particularly in the telecommunications sector towards the end of the decade. But it was also the result of deliberate policy actions; the Fed was willing to avoid tightening monetary policy, despite the unemployment rate falling far below contemporary estimates of the natural rate. They were able to do so due to the last leg of the productivity stool: a stable supply-side and, as a result, low inflation.

Stable Supply and Inflation Allow for Fed Forbearance

All of this growth would not have meant as much if the economy had faced significant inflation. Yet in the 1990s, the US economy was able to avoid the inflationary shocks and cost growth in essentials that upset other recoveries. Unlike the 1970s and 2000s, energy prices were relatively calm in the 1990s. Unlike the 2010s, cost growth in housing services was modest in the 1990s.

In some sectors, this low inflation was just luck. For example, the Asian financial crisis and devaluation of foreign currencies in 1997 resulted in a decline in commodity prices and import prices in raw materials, metals, oil, agricultural products, and consumer goods.

In others, policy played an important role. The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 introduced measures to control health care costs in Medicare and Medicaid, which likely also helped keep health care prices in the private sector in check.

The abundant supply and low inflation of the 1990s was important for productivity for two reasons. The first is that the share of consumer spending diverted to essentials was kept under control. Spending on food, energy, housing and medical care was at its lowest level during the late 1990s.

The strong growth in labor income was not eaten up by higher energy prices or exploding costs. This left more room in the household budget for consumer goods, encouraging firms to invest in new technologies and products.

The second is that low inflation during the 1990s was key to enabling the Federal Reserve to keep monetary policy loose. Throughout the late 1990s, the Fed was always itching to raise interest rates, concerned that an unemployment rate falling below NAIRU was a sign of impending inflation. However, Alan Greenspan was able to convince the rest of the committee to hold off on raising rates as long as inflation didn’t show signs of increasing.

This paradigm, which Alan Blinder and Janet Yellen called “forbearance”, helped keep financial conditions loose through this period, supporting the full-employment economy and the fixed investment boom.

A Full Employment Economy With Productivity Growth, If You Can Keep It

Could we recapture the spirit of the 1990s, today? At the risk of angering the spirit of Harry Truman: on one hand, there are optimistic signs that we are set to repeat the conditions that fostered productivity growth in the 90s; on the other hand, we still have much work to do in stabilizing the legs of the productivity stool.

The economic recovery from COVID, supported by accommodative monetary policy and very expansive fiscal policy, has provided a full employment recovery. Prime-age employment rates have fully recovered and even exceeded their pre-COVID levels. The high level of quit rates during the recovery was a sign that workers were quitting their jobs and moving to others as they climbed the job quality ladder. Quitting rates appear to be retreating as a result of workers getting more settled into their new jobs.

The challenge now is to sustain the full employment economy, so that those workers aren’t thrown back off the job quality ladder by unemployment. While there are no obvious signs of an imminent breakdown in the labor market, many indicators—employment gains, wage growth, and quit rates—show that the labor market has slowed. Monetary policymakers must be on guard against unemployment risks, and conduct monetary policy in a way that preempts those risks.

The situation on investment is mixed. While growth in real investment in some areas, most notably manufacturing structures, is strong (supported by programs such as CHIPS and IRA), investment in other areas is slowing noticeably. Of note, multifamily housing permits have declined over the past few quarters and real private research and development has actually shrunk over the past couple of quarters. In sectors where fiscal policy is not providing direct support, we see investment in further retreat. Even as the effects of monetary tightening are not as readily visible and identifiable with respect to consumption, it has had a more identifiably restrictive effect with respect to fixed investment outcomes.

If monetary policy doesn’t normalize and continues to drag on investment, fiscal policy must do the work of promoting investment. A case study on how policy can support commercial investment in today’s context, see this piece on next-gen geothermal energy from my colleagues Arnab Datta and Ashley George. Supporting the major investments that will be required by the energy transition will sometimes require the government getting out of the way and removing regulatory barriers to building and development.

Building a stable and secure supply side looks like it may require the most work. This inflationary episode, in which the economy ran up against highly inelastic supply constraints in housing, energy, food, microchips, and automobiles, is a stark reminder that we cannot take a steady supply-side for granted.

Hope is not a strategy for ensuring supply side abundance. Outside of HMO-driven healthcare disinflation, the 1990s largely relied on the “luck” of the Asian Financial Crisis to drive down the cost of salient and volatile commodity prices. We should not bet on lightning striking twice in that manner. Supply-side problems are multi-faceted and industry-specific, so this will require a suite of policy initiatives. One angle, which we at Employ America have promoted through our work on the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, is to use stockpiling authorities to manage the supply of critical resources and countercyclically support production. The outsized and somewhat inevitable role for public subsidization in healthcare and education can be transformed into efforts to equitably control costs, as happened in the 1990s and the 2010s. Similar efforts should be considered in the context of higher education policy.

Whether or not we return to productivity growth is at least partially a choice. Public policy may not be able to simply will technological improvements into existence, determine whether AI is actually going to be useful, or meaningfully affect the demographic trajectory of an aging population. What policy can do is ensure that the macroeconomic backdrop is supportive of investments in technological improvements and that the broader economy is in a position to translate those improvements into economic activity.

Also Noah to explain the investment boom please give credit where it’s due to the 1993 Clinton Budget, it contained many tough decisions, significantly reversed Reaganomics and at great pain to Clinton politically (breaking his middle class tax cut pledge) it did what it was designed to do, reduced the deficit to free up capital for private investment

I get very angry that the left refuses to give Clinton credit for its Reaganomics reversing contents but what can you expect from those people but I really wish the centre left and outright centrists would give him credit for the tough decisions that arguably cost him the 94 midterms but did deliver the productivity growth and investment you discuss here as if it just arrived out of thin air, this was in fact the result of tough political decisions that delivered the outcomes they were planned to do (Read The Agenda but ignore the typical Woodward drivebys and focus on the substance)

Sorry- this fellow seems completely ignorant of international economics of the 1990s (globalization and overproduction/over investment abroad helped drive disinflation while increasing supply) as well as micro policy- particularly regulatory and competitive improvements in the US and Europe.

Productivity isn’t caused by Fed policy. Isn’t he aware that his fellow acolytes of the “run the economy hot” school (er- excuse me, “forbearance”) just created the biggest spike in inflation in decades accompanied by sharp falls in real wages?

Is he not aware that, very much unlike the 1990s, both parties wish to constrict competition and supply (except for targeted handouts)? Is he unaware Biden wishes to raise investment taxes and taxes generally (unlike the 1990s in most of the world)?

Is he unaware the frenzied over-investment of the late 1990s led to a bubble and then a crash in stocks, media/telco (particularly relevant and damaging as it was leveraged) and dot com darlings?

Seems to me like he is using one set of questionable productivity numbers (in a period where much of our econ data seems questionable/volatile and still impacted by Covid) to push for the same monetary policy that Brainard and Yellen (and Yellen’s old hires on the Fed economic team) that was disastrous the first time they tried it.

I do believe monetary policy will need to become stimulative again in the years ahead…..because we are going to have a decade of stagnation trying to get out from all of the irresponsible debt we are putting on, particularly since 2020.

If this is accompanied by Biden’s preferred model of high taxes, high regulation and protectionism I wouldn’t be expecting a productivity boom unless it is caused by falls in employment due to AI.