How technology has changed the world since I was young

A bit of future shock.

In 1970, Alvin Toffler published Future Shock, a book claiming that modern people feel overwhelmed by the pace of technological change and the social changes that result. I’m starting to think that we ward off future shock by minimizing the scale and extent of the changes we experience in our life. I tend to barely notice the differences in my world from year to year, and when I do notice them they generally seem small enough to be fun and exciting rather than vast and overwhelming. Only when I look back on the long sweep of decades does it stun my just how much my world fails to resemble the one I grew up in.

Back in March, Tyler Cowen wrote a widely read (and very good) piece about the rapid progress in generative AI. I agree that AI will change the world, usually in ways we’ve barely thought of yet. And I love Tyler’s conclusion that we should embrace the change and ride the wave instead of fearing it and trying to hold it back. But I do disagree when Tyler says we haven’t already been living in a world of radical change:

For my entire life, and a bit more, there have been two essential features of the basic landscape:

1. American hegemony over much of the world, and relative physical safety for Americans.

2. An absence of truly radical technological change…

In other words, virtually all of us have been living in a bubble “outside of history.”…Hardly anyone you know, including yourself, is prepared to live in actual “moving” history.

Paul Krugman made a similar case back in 2011, using the example of how few appliances in his kitchen had changed in recent decades:

The 1957 owners [of my kitchen] didn’t have a microwave, and we have gone from black and white broadcasts of Sid Caesar to off-color humor on The Comedy Channel, but basically they lived pretty much the way we do. Now turn the clock back another 39 years, to 1918 — and you are in a world in which a horse-drawn wagon delivered blocks of ice to your icebox, a world not only without TV but without mass media of any kind (regularly scheduled radio entertainment began only in 1920). And of course back in 1918 nearly half of Americans still lived on farms, most without electricity and many without running water. By any reasonable standard, the change in how America lived between 1918 and 1957 was immensely greater than the change between 1957 and the present.

But when I look back on the world I lived in when I was a kid in 1990, it absolutely stuns me how different things are now. The technological changes I’ve already lived through may not have changed what my kitchen looks like, but they have radically altered both my life and the society around me. Almost all of these changes came from information technology — computers, the internet, social media, and smartphones.

Here are a few examples.

Screen time has eaten human life

If you went back to 1973 and made a cheesy low-budget sci-fi film about a future where humans sit around looking at little glowing hand-held screens, it might have become a cult classic among hippie Baby Boomers. Fast forward half a century, and this is the reality I live in. When I go out to dinner with friends or hang out at their houses, they are often looking at their phones instead of interacting with anything in the physical world around them.

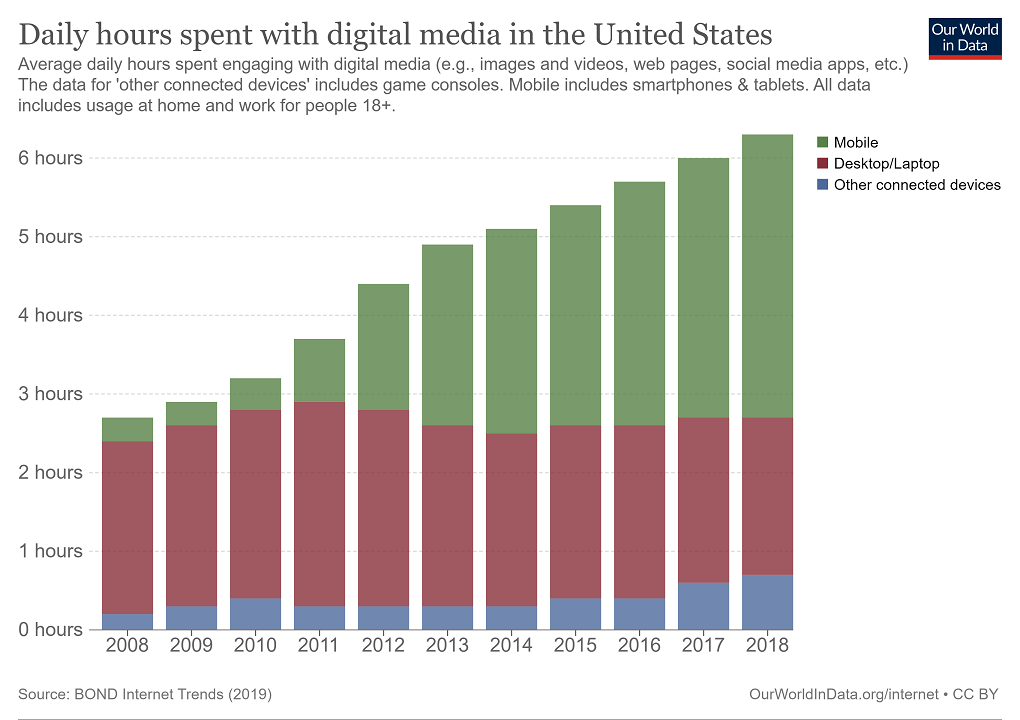

Nor is this just the people I hang out with. Just between 2008 and 2018, American adults’ daily time spent on social media more than doubled, to over 6 hours a day.

About a third of the populace is online “almost constantly”.

All this screen time doesn’t necessarily show up in the productivity statistics — in fact, it might lower measured productivity, by inducing people to goof off more on their phones during work hours. But the reorientation of human life away from the physical world and toward a digital world of our own creation represents a real and massive change in the world nonetheless. To some extent, we already live in virtual reality.

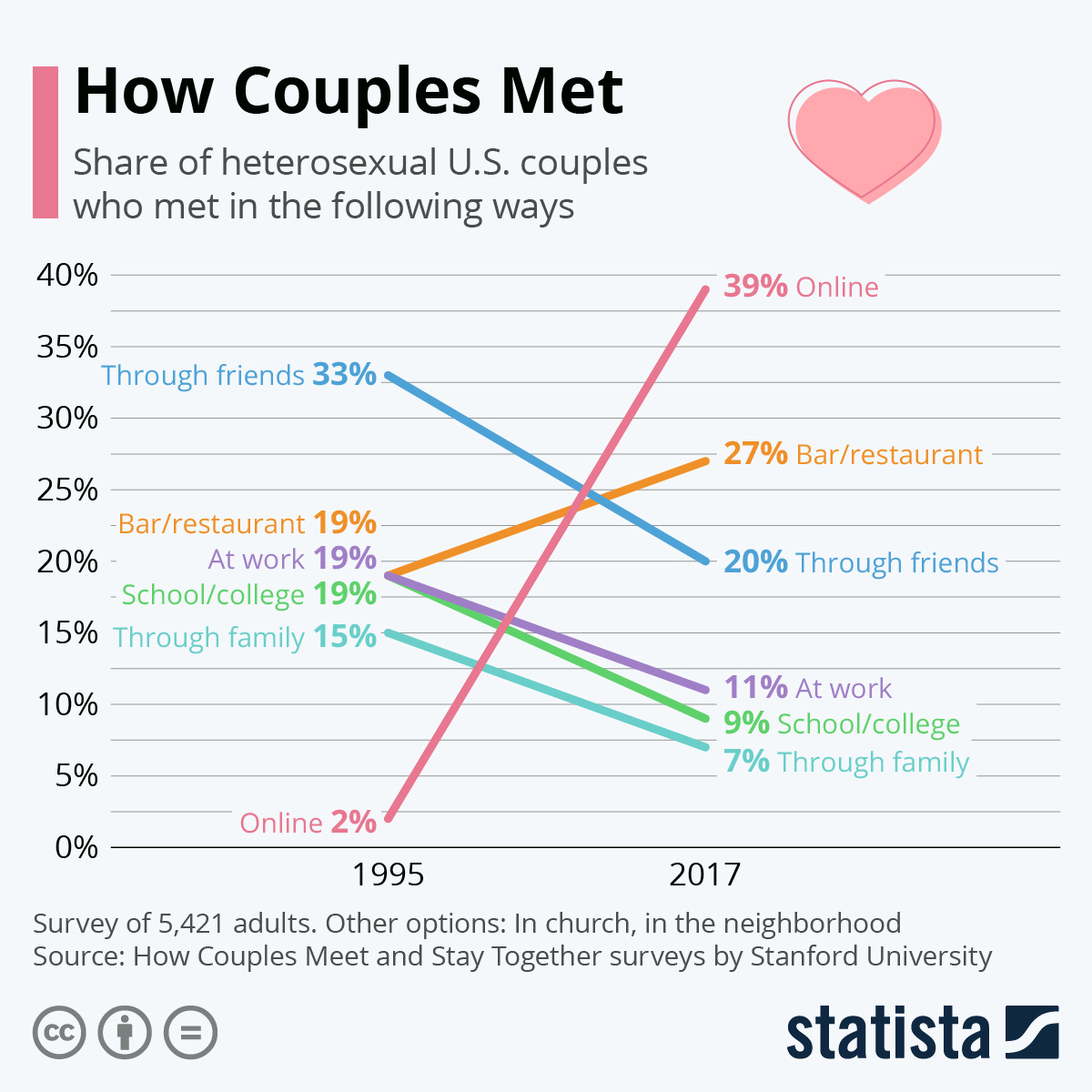

The shift of human life from offline to online has profound implications for how we interact with each other. One example is how couples meet in the modern day. Dating apps have taken over from friends and work as the main ways that people meet romantic partners:

The reorientation of social relationships to the online world is what makes the digital revolution different than the advent of television. TV involves staring at a screen for long periods of time, but it doesn’t let people talk to each other and form social bonds. Arguably, talking to each other and forming social bonds is the most important thing we do in our entire lives — personal relationships are the single biggest determinant of happiness. For almost all of human history, even in the age of telephones, our relationships were governed by physical proximity — who lived near us, worked with us, or could meet us in real life. That is suddenly no longer true.

What broader effects this will have on our society, of course, remains to be seen. One of my hypotheses is that online interaction will encourage people to identify with “vertical” communities — physically distant people who share their identities and interests — rather than the physical communities around them. This could obviously have profoundly disruptive impacts on cities and even nations, which are organized around contiguous physical territory. Perhaps this is already happening, and some of our modern political and social strife is due to the fact that we no longer have to get along with our neighbors in order to have a rich social life.

I once was lost, but now am found

Three decades ago, not getting lost was one of the most important goals of human labor and human social organization. Over the millennia we developed whole systems of landmarks, maps, directions, road names, and even social relations in order to make sure that we always knew how to find our way back to security and shelter. The possibility of getting lost was an ever-present worry for anyone who drove their car, or walked in the woods, or took a vacation to a strange place.

And now that foundational human experience is just…gone. Unless your phone runs out of battery or you’re in a very remote wilderness area, GPS and Google Maps will always be able to guide you home. Much of our physical and social wayfinding infrastructure, built up over so many centuries, has instantly been obviated — you don’t have to plan your route or ask for directions, you don’t have to keep close track of landmarks as you drive or walk, you don’t even have to remember the names of roads. The forest has lost its terror.

Of course, there was another kind of fake “getting lost” that could be quite fun, and that’s gone too. It was exhilarating to wander around in a foreign city not knowing what was around you, hunting for restaurants and shops and new neighborhoods to explore. You can still do that if you want, but it’s just imposing unnecessary difficulty for fun — you can just open Google Maps and find the nearest cafe or clothing store or museum or historical monument.

And there’s also a big and important flip side to the fact that no one gets lost anymore — as long as you have your smartphone with you, someone, somewhere, is always able to know where you are. Your location is tracked, wherever you go, even if Apple or Google is nice and respectful enough not to let humans look at that data. China, of course, has far less concern for privacy. But even where privacy rights are respected, governments and corporations are still capable of easily tracking your every move if they feel like it.

Mystery has gone out of the world

I still remember a moment in 2003 when I idly wondered what the Matterhorn looked like. In 1990, answering my curiosity would have required that I go open an encyclopedia, or — if my encyclopedia didn’t have a photo of that particular mountain — to go through the library searching books for a picture. But in 2003, I just typed “Matterhorn” into Google image search, and the picture appeared.

Over the last two decades, there has been a massive proliferation of tools that convey enormous amounts of knowledge, on demand, to anyone who wants it. Wikipedia can teach you the basics of anything from math to history to geography. YouTube tutorials can show you how to fix things in your house, ride a jet ski, or cook a restaurant-quality meal. Google can tell you what anything looks like, or point you to any scientific paper on any topic. And they can give you all this knowledge on demand, from the little screen that you carry with you everywhere, whenever you want it.

This has changed the nature of human life. Just a few decades ago, the knowledge contained in human heads was of utmost importance. If your cabinet was loose or your drain was clogged, you had to know a human being who could fix it. If you wanted to know interesting facts about the world, you had to either ask a human being who knew those facts, or go on an exhaustive search. Wisdom and know-how were profoundly valuable personal attributes. Now they’re much less of a reason for distinction.

Now it’s important to note that understanding and practiced skill are still scarce commodities. YouTube can’t teach you how to be a great violinist (at least, not in 30 minutes), and Wikipedia can’t give you the ability to do difficult math proofs. And the knowledge that can be gained from direct experience is often superior in quality to the knowledge gained from a Google search — for example, if I actually go to the Matterhorn, I can see it from a variety of angles and in a variety of lighting. But overall, humans have taken much of the knowledge that they used to have to carry around in their heads and uploaded it to what is, in effect, a single unified exocortex.

But if ignorance (or at least, the accidental kind, rather than the willful kind) has diminished, mystery has also shrunk. Exploring remote locations, rare objects, and esoteric knowledge is no longer difficult enough to generate quite the same sense of adventure and wonder it once did. Just as GPS has taken some of the adventure out of visiting strange places, the vast sea of internet knowledge has made many other forms of exploration quotidian.

And there’s another kind of mystery that the internet has either eliminated or vastly reduced — the mystery of not knowing other people. In 1990, if I wanted to know what Indians thought about American politics, I’d just have to wonder. Now, I can just open Twitter and ask, and a bunch of Indian people will be happy to inform me of their views. In 1990, talking to someone from another country was a rare and exotic treat; now, it’s just something that we do every day without even really thinking of it. That’s the first time that has ever happened in the history of humankind.

The Universe has memory now

The internet doesn’t just find things for us or allow us to communicate; it also stores information in much larger volumes than books, TV shows, or any other medium that came before. Practically everything you’ve ever typed on the internet is still on the internet. As recently as a few decades ago, most of the things you said and did would be forgotten and misremembered after a fairly short time; now they’re frozen in silicon and magnets.

This has some obvious major consequences for the shape of human life. When you can be “canceled” by an online mob as a 35-year-old for something you said as a teenager, that requires people to be more on guard about what they say for their entire life, even as kids. When any prospective business partner or lover can Google you and find your background (unless you erase it, in which case the prospective partner will be justifiably suspicious), the ability to craft a new persona for yourself, and move beyond the baggage of the past, is limited. On the other hand, remembering what you were like at a younger age, or an argument that you made in a debate a few years ago, is now quite easy. And it’s a lot easier to keep in touch with old friends now.

Technology’s memory involves images and video as well, thanks to the explosion of digital cameras and the increasing capacity of hard drives. Many of the memories we want to preserve in life — our interactions with our offline friends, the places we traveled, the places we lived — now get stored on a hard drive.

Technology weirds the world

A lot of economists tend to think of technological change as being embodied in total factor productivity growth, which has slowed down since 1973 or so. But first of all, there are plenty of things that go into TFP growth besides what we typically think of as technology — there’s education, geographic mobility, a demographic dividend, and so on. As the economist Dietz Vollrath has shown, these factors can explain the entire productivity slowdown, with no need to appeal to a slowing rate of technological progress.

But even more fundamentally, technology changes the world in ways not directly captured by the monetary value of goods and services sold in the market. If our daily activities are redirected toward different sorts of relationships and interactions, that isn’t necessarily something that we’d pay a lot of money for — and yet it means human life is now an entirely different sort of endeavor. If we’re constantly surveilled by corporations and the government, that’s probably something we don’t want, and thus will not pay extra money for, even if rebelling against it would be too much of a hassle for most. And so on.

Sometimes technology grows the economy, but more fundamentally, it always weirds the world. By that I mean that technology changes the nature of what humans do and how we live, so that people living decades ago would think our modern lives bizarre, even if we find them perfectly normal. The information technology boom may not have goosed the productivity numbers as much as many hoped, but it has nevertheless left a deep and transformative impact on the shape of human life.

I’m excited to see if AI brings us a world of radical technology-driven change. But you and I have already been living in a world of radical change for decades now. Maybe the tendency to believe progress has slowed — to focus on the stagnation in our kitchens and not the fact that the world has suddenly become far more transparent, comprehensible, and recorded — is a way of avoiding future shock. But man, when I think of 1990, I can’t help but feel a little overwhelmed by how far we’ve come.

I'm in the 1x 10‐⁸ of the heterosexual meet your spouse category. Maybe alone. I met my wife on the side of the road. Fixed her car. Nighttime. Married her 9 months later, 46 yrs ago.

I still have my 1950s one transistor am radio I used to hear the World Series.

Being an early 1970s tech nerd at 3 letter geek school in Boston, I see the smartphone as they key leap..I think you highlight screen time. That's me now!

But for me (69) and my wife (73), the access to information, to learn things, to satisfy curiosity, is fantastic! We have thousands of books and still research and read from them. Turns out not everything is on the internet.

Excellent article! The one thing I’d quibble on is this line: “Wisdom and know-how were profoundly valuable personal attributes. Now they’re much less of a reason for distinction.” I think if anything, the explosion of ubiquitous information has placed a *premium* on wisdom over superficial facts.

You provide a few good examples of how experience can be superior to online activity (ie learning violin), but I think it goes deeper than that. The critical skill is no longer just...knowing a thing, but rather how to connect it to the 8 million other facts and narratives fighting for attention. The ability to construct meaning from data is what people increasingly crave, and I think you can see this with the rise of Vox explainers, Substackers who focus on technical areas, and subject matter experts becoming Demi-celebrities on Twitter and tik tok.

A great example of this was during covid. There was a glut of information, even in those early months, but they were all disconnected fragments and people struggled to make sense of it. A then-unknown genomics professor from the Hutch in Seattle named Trevor Bedford was able to rise to prominence by not just posting his own data and other research, but crafting long, methodical Twitter threads that walked lay people through the data in a clear, fun, and non-inflammatory way. He later won a MacArthur Genius award, and while he’s clearly a bright scientist, I highly doubt he would be on the committee’s radar if not for his public science communication work.

Similar things seem to be happening right now with AI. When every person on the planet can use it to become a decent writer, the truly great writers will stand out above the sea of uniform mediocrity, rather than a bell curve of quality. When anyone can ask ChatGPT for factoids about something random like microRNA or particle physics and get a B-minus answer, the people who can weave a story, and more importantly use the data effectively, will become in high demand as consultants, speakers, and employees, while other knowledge workers that can’t rise above the crowd are at risk of automation.