How much of modern academia is waste?

A painful question that we need to ask.

I’ve spent many years defending America’s university system from critics on the political Right. For example, in 2017, in response to a GOP plan to increase taxes on some university activities, I wrote:

The U.S. university system is one of the country’s most important remaining economic advantages. Even as manufacturing industries have moved to China, the U.S. has retained its dominance in higher education. The research and technology output of American universities, and the skilled postgraduate workers they produce, are an important anchor keeping knowledge industries -- Silicon Valley, the pharmaceutical industry and the oil services industry, to name just three -- clustered in the country, instead of fleeing to places with lower labor costs. Degrade higher education, and the U.S. will become a much less attractive place for cutting-edge industries, and less important to the global economy.

This is all still true. But seven years later, I’m more convinced that our university system needs greater outside scrutiny and even criticism in order to fix its problems, in order to make sure that this remains true.

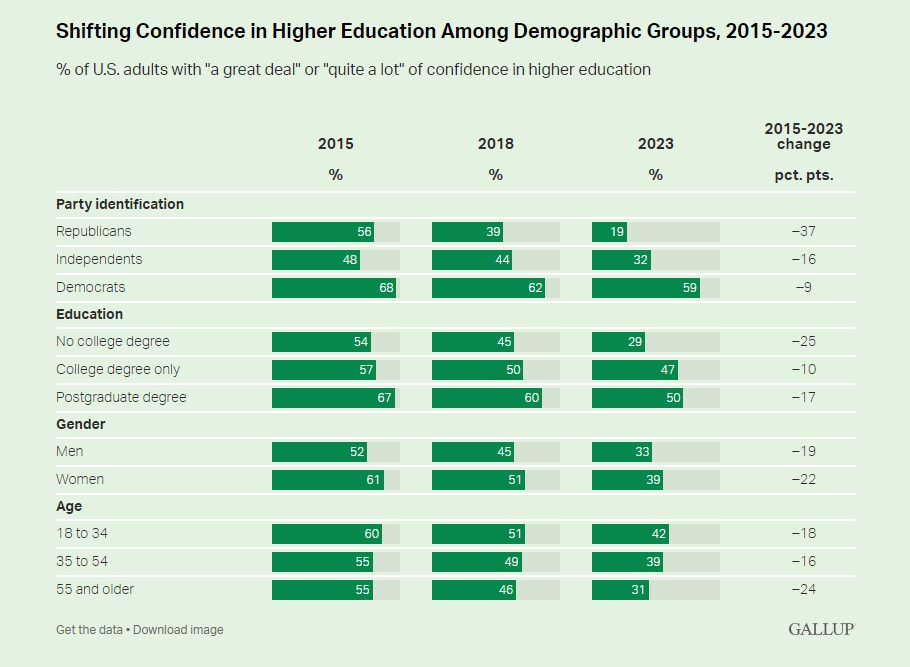

Confidence in America’s colleges has been falling — not just among Republicans, but Democrats as well.

The recent plagiarism scandal at Harvard has turned up the heat. Josh Barro, in a provocative post entitled “Universities Are Not on the Level”, argues that the problem is that colleges have embraced pervasive dishonesty:

For me, the problem starts with the replication crisis…[T]he [social psychology] studies I learned about in class keep getting debunked, with replications failing and the studies often having been p-hacked or even based on fraudulent data…I can’t be the only one wondering how much longer Dan Ariely is possibly going to remain a professor in good standing at Duke…

Matt Yglesias wrote a few weeks ago about a paper by Jenny Bulstrode, a historian…who alleges that a moderately-notable metallurgical technique patented in England in the late 1700s was in fact stolen from the black Jamaican metallurgists…The problem with Bulstrode’s paper is that it marshals no real evidence for its allegation.

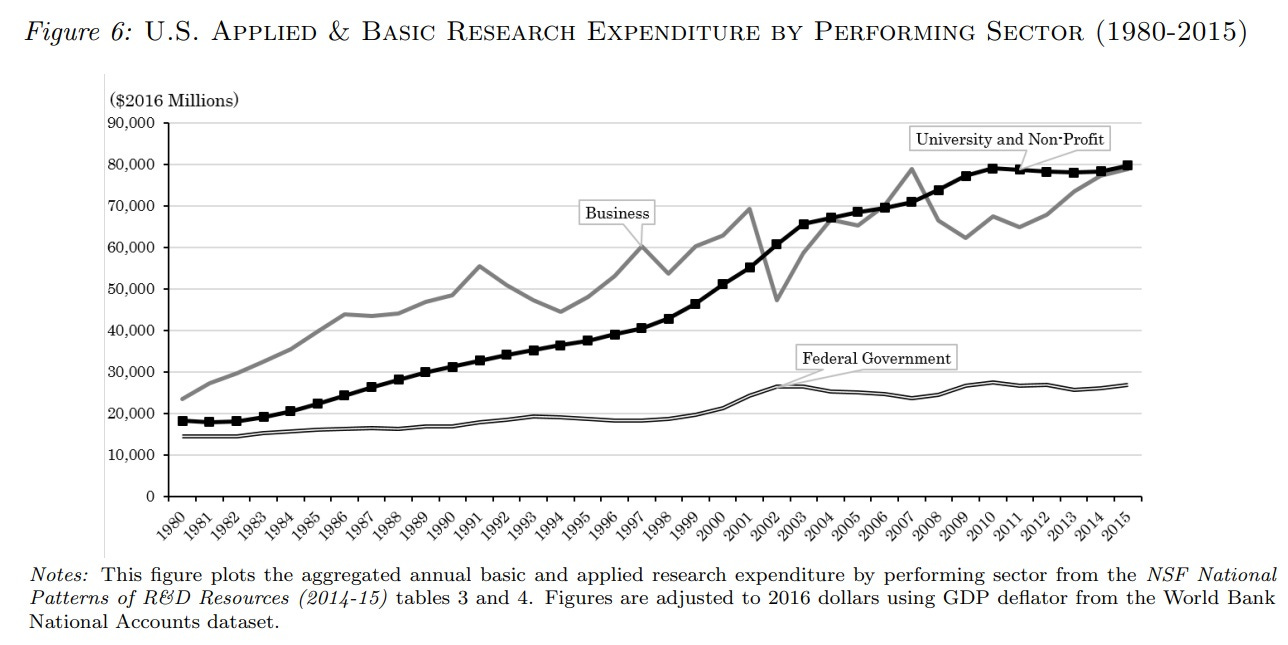

Barro also discusses dishonesty in hiring practices, admissions, and other aspects of campus life. But it’s his points about dishonest research that really hit home. My defense of the university system from its conservative critics was always based on the research that universities do. Although we tend to think about colleges mostly in terms of their education function — because this is how most Americans interact with the university system over the course of their lives — the research function is arguably even more important to our nation. Over the last 40 years, universities have taken on ever more of the research burden:

This research is crucial not just for increasing human knowledge, but for powering the private sector as well; Tartari and Stern (2021) found that every $1.6 million in government research grants to universities ultimately creates $50 million in startup value!

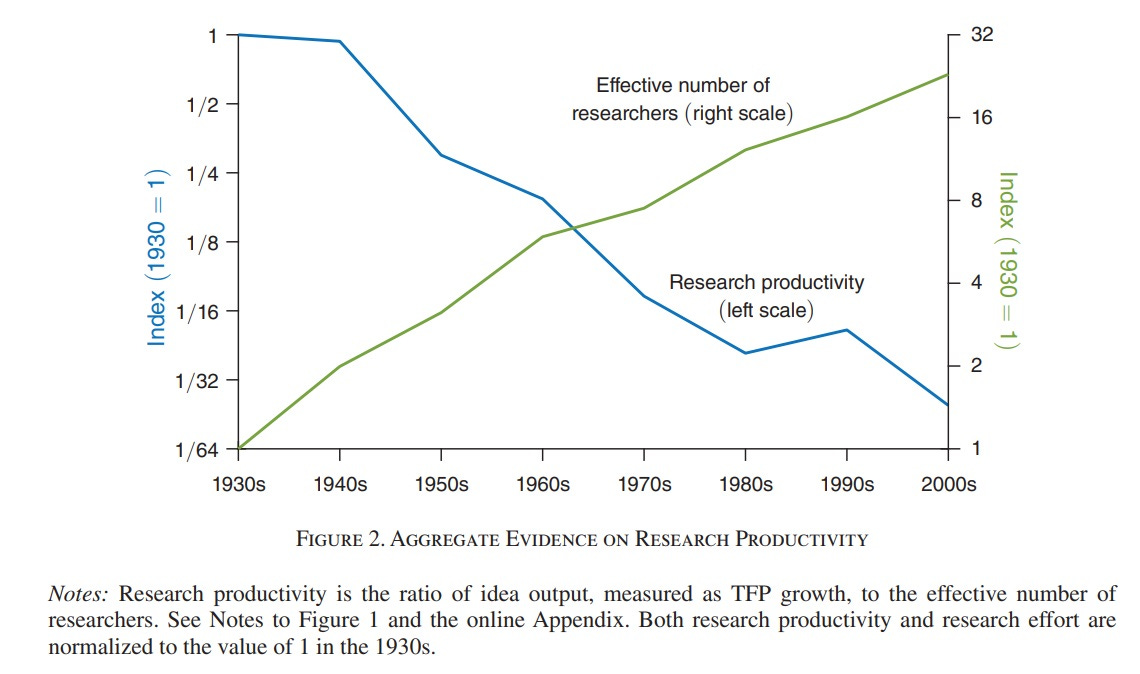

And yet something else has been happening during this time: Research productivity, as measured by the amount of total factor productivity growth relative to research spending, has been going steadily down.

Now this doesn’t mean research is no longer worth spending money on (it is). Nor does it mean universities are solely to blame for this trend, since it’s been in place since well before universities became dominant. A lot of this may simply be a case of ideas getting harder to find, or of the U.S. throwing more money at marginal (but still valuable) research projects, or of research results not getting commercialized.

But given the pivotal role that universities now play in our research ecosystem, and given the replication crisis in psychology, medicine, and other empirical disciplines, it makes sense to ask if our universities are wasting national resources by producing too much useless or misleading research.

This is a painful question to ask, because so many of us (myself included) came up through the academic system, or still work there, or have friends and family who work there. And it’s a question many progressives will be uneasy about, given the lurking menace of conservatives who want to gut universities for culture-war reasons unrelated to research productivity. But it’s a question we need to ask anyway, because the massive concentration of talent in our research universities is among our most valuable national resources, and we need to think about whether the incentive system we’ve created is putting that resource to good use.

Measuring waste is really hard

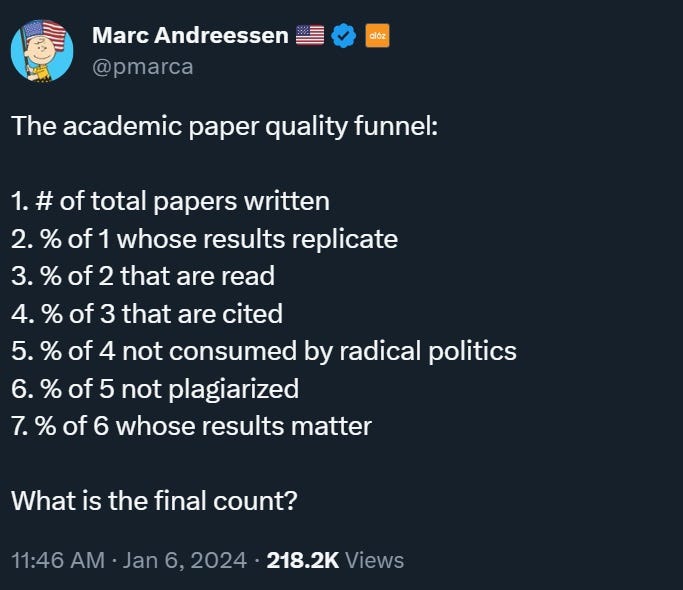

It’s incredibly difficult to quantify research waste. One way is to think about the steps involved in the research production process, from publication to application. Marc Andreessen came up with a breakdown:

Honestly, the only one I’m really worried about is the last of these. Let me explain why.