How Latin America started to beat inequality

It can be done.

When economists or pundits in the U.S. want to issue dire warnings about rising inequality, they have a tendency to clear their throat, push their glasses up the bridge of their nose, and say “We’re approaching Latin American levels of inequality.” But it’s not just a ghost story, used to frighten politicians — Latin America probably is the most unequal region in the world:

Exactly why the region is so unequal is up for debate. Explanations typically focus on the region’s colonial history, which created highly unequal land ownership. The region never had a major program of land reform to forcibly redistribute farmland from landlords to tenants, as many countries in Asia did. The other big industry, mining, tends to be highly concentrated as well; some economists blame this on the region’s colonial history as well.

Others argue that the problem is more recent. For example, Williamson (2015) writes:

Compared with the rest of the world, inequality [in Latin America] was not high in the century following 1492, and it was not even high in the post-independence decades just prior [to] Latin America’s belle époque and start with industrialization. It only became high during the commodity boom 1870-1913, by the end of which it had joined the rich country unequal club that included the US and the UK. Latin America only became relatively high between 1913 and the 1970s when it missed the Great Egalitarian Leveling which took place almost everywhere else. That Latin American inequality has its roots in its colonial past is a myth.

One possibility is that global economic geography forced Latin America into becoming a commodity exporter instead of a manufacturing nation. Because the region has so much farmland and so many valuable minerals, and because it’s relatively sparsely populated and far from the world’s main industrial clusters in Asia and Europe, developing manufacturing was hard. Only a couple of Latin American countries — Mexico and El Salvador — have managed to specialize in manufacturing. This could have limited the scope for institutions like unions and labor laws to equalize the distribution of income, as well as robbing Latin American governments of the incentive to improve education (which would raise human capital and middle-class wages).

But in any case, there’s another very important fact that everyone should know about Latin American inequality: It’s falling.

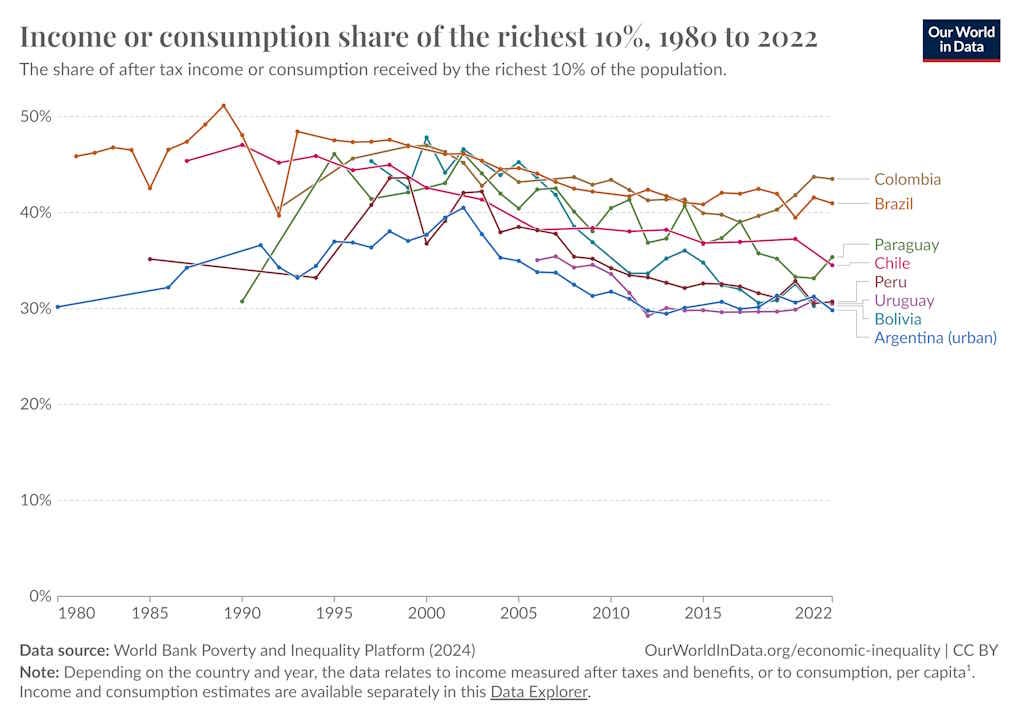

There are a bunch of different ways of measuring economic inequality — the Gini index, income shares, wealth shares, and so on. But as far as economists can tell, all of these measures have been trending downward since around the turn of the century. Here’s the income share of the top 10% of society in South America:

And here’s the graph for Central America, where the story is similar or even better:

(Data for Venezuela isn’t available.)

This hasn’t solved the problem — the region is still more unequal than most others — but it does represent pretty incredible progress. Importantly, the pandemic doesn’t seem to have interrupted the trend.

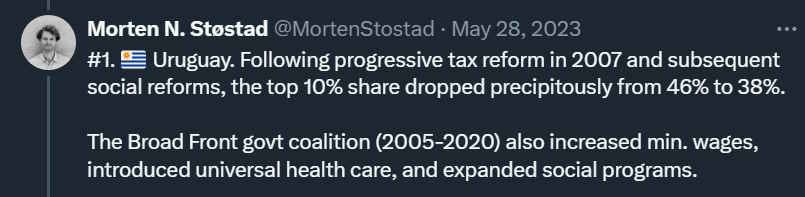

So what happened? The most common explanation is also the simplest: Latin American countries elected center-left leaders who redistributed more income and implemented other policies like minimum wages. For example, Morten N. Støstad has a thread where he lists the countries that reduced inequality the most from 2005 to 2020 — four out of five are in Latin America — and argues that progressive policy is the cause. For example, here are his explanations for Uruguay and Ecuador:

This makes for a nice, simple story: Elect center-left governments, and they will redistribute more, and then your country will be more equal. Electing far-left governments is more of a gamble — Bolivia’s Evo Morales and Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega brought inequality down, but Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez and Nicolás Maduro destroyed their country’s economy utterly. So sticking with center-left types like Brazil’s or Chile’s Boric seems like a better idea. In fact, Latin America has generally been in a mood to elect center-left governments recently.

But when economists look deeply into the causes of Latin America’s declining inequality, they find that the true story is more complex. Although it’s a decade out of date at this point, Lustig, López-Calva, and Ortiz-Juarez (2016) is still the most comprehensive, detailed paper I’ve found on the topic. It needs an update, but it’s definitely a paper you should know. Lustig also has a good set of slides that describe the paper’s findings.

Lustig and her coauthors note that the decline in inequality across the region seems to have little correlation with what type of party the countries elected — inequality fell in countries that elected conservative governments too. Interestingly, Mexico and El Salvador, whose main exports are manufactured goods, saw inequality fall just as much as in their resource-exporting neighbors.

What about progressive transfers? The authors find that although increased redistribution does account for maybe 17% of the drop in inequality from 2000 to 2012, the biggest factor by far was a reduction in pretax wage inequality, explaining 62% of the decline. In other words, the poor and middle class started earning more money in Latin America in 2000-2012.

Why did that happen? Lustig et al. examine a number of studies that try to figure out the cause of declining wage inequality in various Latin American countries over this period. The progressive state does get a bit of the credit, since some Latin American countries raised minimum wage, and a few boosted the power of labor unions. But inequality also fell in countries that didn’t do these things.

What did affect pretty much every country in the region, however, were two things: 1) faster economic growth, and 2) increased education.

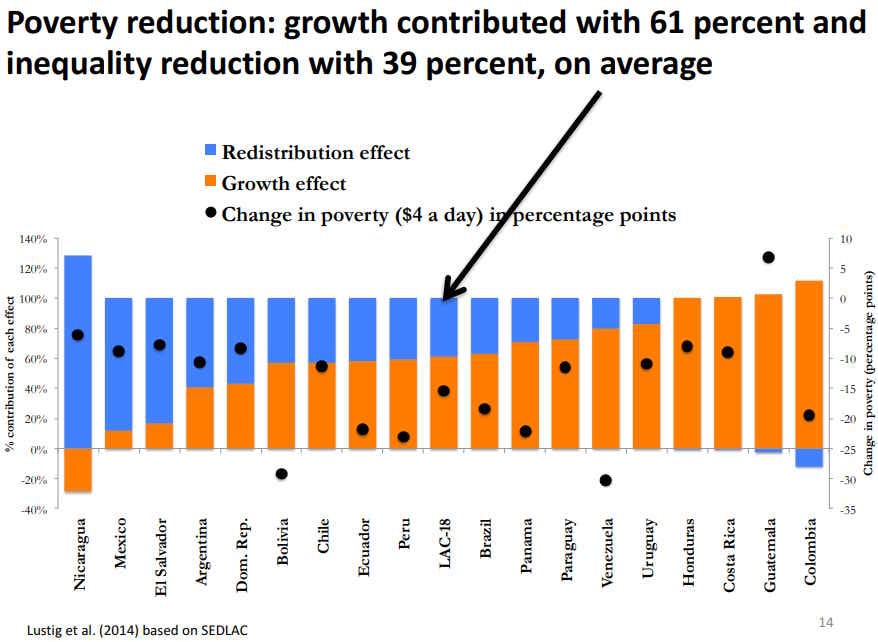

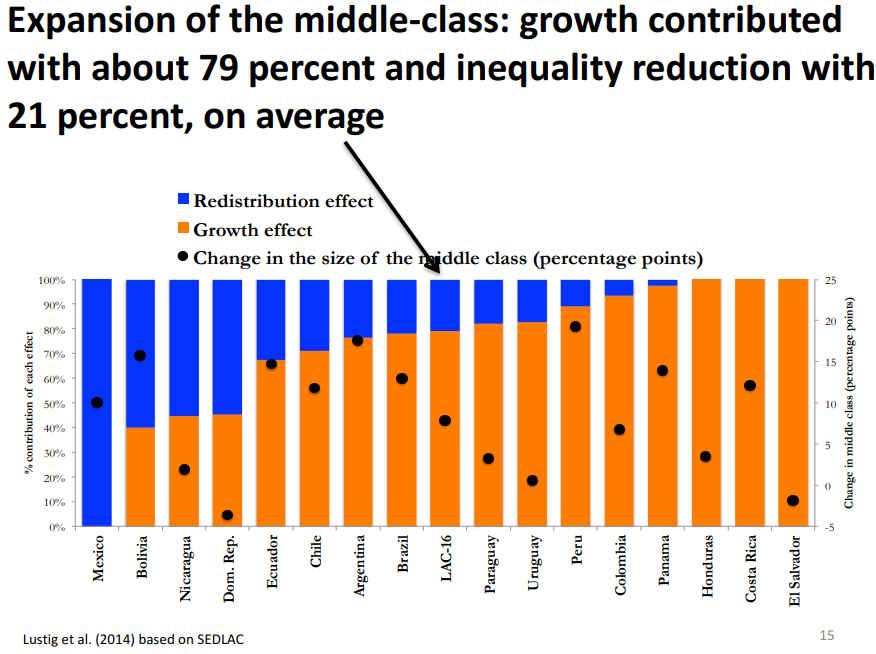

Lustig et al. estimate that from 2000 to 2012, faster economic growth was responsible for the lion’s share of the growth in the Latin American middle class, and for a majority of poverty reduction as well. This wasn’t true in all countries, though; in some, redistribution mattered more. Here are a couple of graphs from Lustig’s slides:

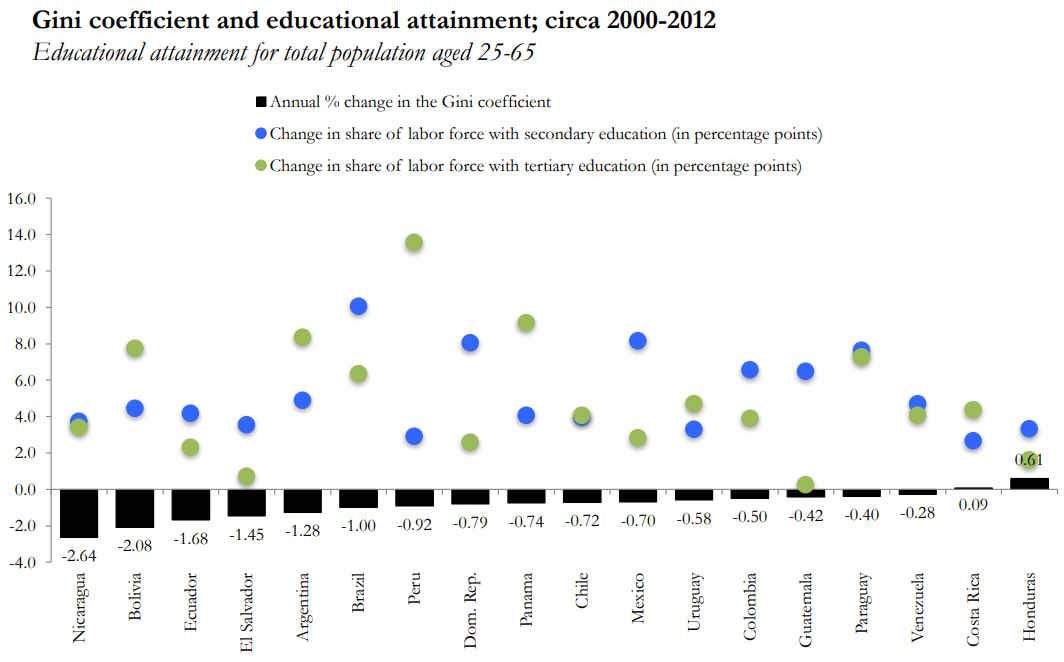

But why was this growth so broad-based? Why were the benefits shared so equitably, instead of mostly flowing to the top 10%? Lustig et al., and most of the other studies they cite — as well as some they don’t cite — suggest that the key factor was education. In the 90s and 00s, Latin America made big strides in school completion at both the secondary and tertiary levels. Pretty much every country got a lot better-educated:

Education allows workers to take a bigger slice of the pie. It increases their productivity, making them worth more to employers. And it also probably increases their bargaining power, since it makes them better able to understand their true worth as employees, savvier about switching jobs, and so on.

Better education boosts growth, especially in countries like Latin America where education had traditionally lagged. And it boosts growth in an equitable way, because when a larger chunk of the population is educated, the “skill premium” falls — you don’t just have a few elite workers taking all the cash, because they’re suddenly in direct competition with a much larger educated workforce.

So this is the likeliest story of Latin America’s great inequality decline. The region still has far to go, of course. And there’s still the possibility that the decline could reverse itself; Colombia in particular shows dangerous signs of backsliding. But overall, the lesson is clear: Improve education, improve growth, and do some progressive transfers, and inequality will fall. The key isn’t just to elect left-of-center leaders — you need left-of-center leaders who also care about growth and who pay special attention to the value of education.

The old adage about teaching a man to fish really seems to be true.

Why this fetish for equality? Isn't absolute wealth more important? If I'm poor, I'd be happy to double my income and gain ground on a rich guy, but I'd be even happier to triple it, even if the rich guy quintuples his, making inequality "worse."

I understand that inequality can cause a lot of resentment, but I think that can be greatly mitigated if the poor are getting richer in absolute terms.

North America: Canada, US, Mexico

Mexico is NOT part of Central America; though it’s part of Latin America.

It pisses off (this Mexican) to no end when Mexico is grouped w Central America.