I’m in transit today, flying to Japan (again). So here’s a Japan-related repost from the early days of this Substack. Between an immigration boom and a tourism boom, Japan has become much more internationalized in recent years, especially in Tokyo and Kyoto. But in fact it was never as homogeneous as people thought. All of the takes you see that rely on the idea of Japan as some sort of racially pure, xenophobic, closed-off nation are pretty much nonsense. Then again, if you see people making those takes, maybe it’s better not to correct them; after all, that might make them more eager to move to Japan!

If I hear “Japan is a homogeneous society” one more time, I’m going to write a long angry blog post. Oh wait…this is that blog post.

When you hear the words “homogeneous society” uttered in conversation in America, people are almost always talking about either Scandinavia or Japan. To some on the Right, Japan is a paradise of racial purity, while to some on the Left, it’s a bastion of xenophobia and isolationism. The one thing they agree on is that pretty much everyone in Japan is Japanese, and that the government is intent on keeping it that way.

So are they right? Well, I’m going to restrain my impulse to say “NO, YOU’RE ALL WRONG, YOU FOOLS, YOU DON’T UNDERSTAND JAPAN AT ALL,” because it actually is an interesting and rather subtle question. It depends on what “homogeneity” means, both to us Americans and to Japanese people themselves. And that leads to some interesting questions about identity, nationhood, and public policy.

BUT, before asking those questions, we need to get some facts.

Isn’t Japan 98% Japanese?

One of the most common statistics I hear in these discussions is that Japan is “98% Japanese”. In fact, the 2018 Census did report that 97.8% of the population is “Japanese”. (Though it’s noteworthy that this is down from the traditional “99%”.)

But what most people don’t seem to understand is that “Japanese” here means “citizen of the country of Japan”. It is not a measure of race or ethnicity. It includes native-born citizens of minority races, plus naturalized citizens. The equivalent number for the United States is 93.3%.

If I told you that the U.S. was “93.3% American”, would you conclude that the U.S. is a homogeneous country? Because that’s exactly what everyone who cites the “98% Japanese” statistic is doing for Japan.

OK, so how much of Japan is ethnically Japanese? Well, first of all, the ethnicity we casually refer to as “Japanese” is formally known as “Yamato”. And as for the percent of Japan that’s Yamato ethnicity, we don’t actually know that, because the government doesn’t keep track.

Yep, you read that right. Japan’s government doesn’t go around asking people what race they are. A curious behavior for a country that’s supposedly obsessed with racial purity, no? We’ll come back to that in a bit…

Anyway, there are probably some high-quality private-company surveys on ethnic self-identification in Japan, but I don’t have them right now. I will try to track them down. In the meantime, various sources put the Yamato percentage at around 90% or a bit higher. That’s pretty high — about the same as the percent of Americans who identified as “white” in 1950. But even includes people of mixed ancestry (like one of the anime characters depicted in the image at the top of this post). And since marriage is a significant way that non-Yamato people immigrate to Japan, the percentage of Japanese people who are descended purely from self-identified Yamato people is going to be even lower than 90%.

And of course these percentages don’t take local variation into account. In 2018, 1 out of 8 people coming of age (i.e. turning 20) in the city of Tokyo was foreign-born, a figure that doesn’t include ethnic minorities or people of mixed ancestry. Add that to the massive pre-COVID tourism boom, and Japan’s capital city definitely no longer feels very homogeneous.

But they’re all Asian, right?

Western tourists who go to Japan often feel like they’re in a homogeneous country, because they look around and everyone looks East Asian. In fact, in recent years, lots of the people they’re seeing were actually Chinese tourists, who swamped Japanese cities before COVID-19 struck. And given that they can’t even tell tourists from locals, it is highly unlikely that Westerners walking down the streets of Tokyo, looking around and saying “Hmm, everyone here looks Japanese to me” are capable of identifying residents of Korean, Chinese, or Brazilian descent.

And indeed, in Western society, ethnic distinctions within racial minority groups like “East Asians” are often glossed over. But in Japan these differences are real and salient. The hate groups who marched through ethnically Korean neighborhoods in the early 2010s with signs saying “Death to Koreans” definitely see a distinction. Brazilian residents are actually mostly of Japanese descent — they look as Asian as anyone — but are treated as a separate ethnicity and often face discrimination. And so on.

So even if Americans wouldn’t recognize a group distinction walking down the street, these distinctions are important in Japanese society. In other words, the ethnic diversity that Japanese people experience is greater than the diversity that outsiders ascribe to the country.

“One nation, one civilization, one language, one culture and one race”

In 2005, then-Foreign Minister Taro Aso declared that Japan was a country of “one nation, one civilization, one language, one culture and one race”. He was not the first Japanese politician to use those terms.

Given the data above, it’s obvious that this was an aspirational statement rather than a factual one — a call for Japanese people to think of their country this way. It was a desire to create homogeneity out of diversity, through cultural and linguistic assimilation and through identification with the Japanese nation. In fact, this sentiment is probably one big reason why the Japanese government doesn’t ask citizens about their ethnicity — it wants them to think of themselves as all being Japanese.

In fact, this impulse toward homogeneity doesn’t just work at the level of nationhood, but in terms of ethnicity as well. Just as many Americans whose ancestors have been in the country for a long time come to identify as “white”, Japanese people whose ancestors have lived in Japan for a while come to identify as “Yamato”. Race and nationhood are even more intertwined in Japan than in the U.S. The minorities that exist — Koreans, Brazilians, and so on — are generally excluded based on citizenship status rather than linguistic or physical differences. Japan doesn’t have birthright citizenship, so many native-born residents of Japan, who speak no language other than Japanese, hold foreign passports.

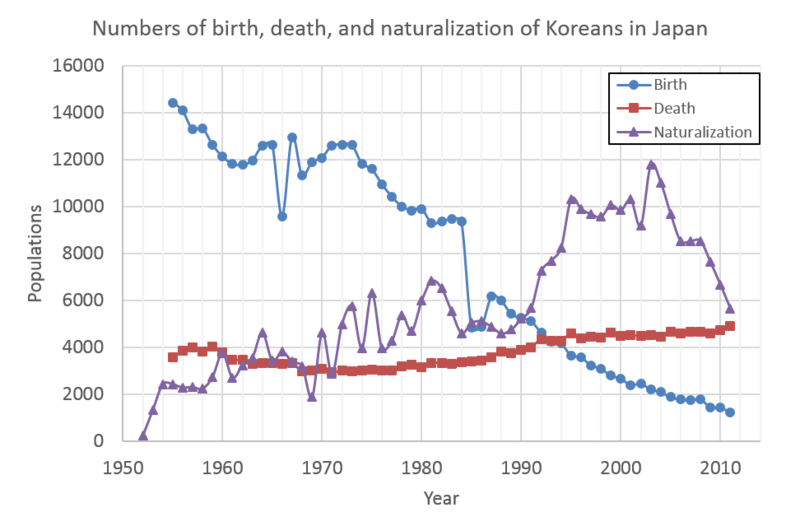

This is how Japan tends toward homogeneity as time goes on. Zainichi Koreans, Japan’s largest and most prominent minority, have been steadily becoming Japanese through intermarriage and naturalization.

Of course, here’s where visual distinctiveness does end up mattering. If a guy who looks like Masayoshi Son tells you he’s “Japanese”, it’s pretty easy to just accept that as fact. In fact, Son IS a Japanese citizen, and the only reason people think of him as being part of the Korean minority is that he’s famous enough that the media looked up and reported his ancestry.

But for someone like Ariana Miyamoto, it’s a lot harder for some Japanese people to accept that she’s “Japanese”. In fact, when Miyamoto won the Miss Universe beauty pageant in 2015, there was a ferocious racist backlash, leading other Japanese people to jump in and defend her.

In other words, the rise of visually distinctive Japanese nationals is now forcing Japan to struggle with some of the same issues of appearance, race, identity, and nationhood that other rich nations are now dealing with. For a good in-depth coverage of these issues and struggles, I recommend the 2013 documentary “Hafu: The Mixed-Race Experience in Japan”. Encouragingly, racial exclusion seems to be losing the debate in Japan for now, as evidenced by the far smaller backlash against Japan’s second mixed-race beauty queen, Priyanka Yoshikawa.

A normal country, struggling to be culturally homogeneous

Japan is not an island of racial purity. Instead, it is a fairly normal rich country, dealing with fairly normal issues of immigration, diversity, minority rights, racism, and nationhood. A lot of these debates look similar to those in Europe or the U.S., such as when Nike ran an ad in Japan featuring the bullying of minorities, and encountered a mixed reaction.

Japan’s distinctiveness in these areas is relatively minor. The country was late to get in on the immigration trend, but finally started opening up under Prime Minster Shinzo Abe in 2013:

Japan’s dogged pursuit of homogeneity through nationalism and assimilation is also not particularly unusual — it’s much less heavy-handed than Denmark or France in this regard, or even than the U.S. in the early 20th century. The refusal to gather statistics on ethno-racial diversity is unusual (UPDATE: Turns out France is the same!), but it remains to be seen whether simply having statistical agencies ignore diversity will produce greater homogeneity over time.

Whether Japan’s leaders will continue to seek homogeneity, or embrace some form of multiculturalism, remains an open question. And it’s also not clear who Japanese people will continue to think of as a minority, or how Japanese racial and national identity will be conceived of in the future. But what should be clear is that Japan is a lot less unusual in these dimensions than many Westerners believe.

I know that the immigrant countries with birthright citizenship are the outliers here, but when you tell me that the largest minority group in Japan faces discrimination, calls for their death, and exclusion from citizenship despite having lived in Japan for generations, speaking Japanese, taking Japanese names, and only being there in the first place due to Japanese colonialism… I dunno, man, that sounds kinda racist and xenophobic!

you mention Brazilians several times in your article. You should expand on that and explain why these Japanese-descent Brazilians are there in the first place, namely an explicit policy back in 80s-90s (when Japanese industry needed workers not yet because of low birth rates but because of booming economy) to import these "Japanese-blooded" people as guest workers on the (mistaken) assumption that because they looked Japanese that they were also culturally etc. similar. They could've imported labor more cheaply from nearer but went across the world to hunt for these hopefully more racially compatible imports. Can't think off top of head of another similar example. It's like Germany in 70s deciding to get workers from US citizens with German ancestry rather than from Turkey, or something.