How are the post-Soviet economies doing?

Prepare for a whole lot of graphs.

Today (well, yesterday, by the time you’re reading this) is the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Soviet Union, one of the most momentous geopolitical events of my lifetime. The main reason this was important wasn’t economic — it was proof that the fall of a superpower didn’t mean nuclear holocaust. And it meant the end of the Cold War, which brought a massive reduction in nuclear stockpiles.

As for why the USSR fell, this is a complex question involving political, geopolitical, and economic factors. Regarding the latter, I recommend Yegor Gaidar’s Collapse of an Empire. Short version: The Soviet economic system was dysfunctional, leading to a greater and greater dependence on fossil fuels, which couldn’t be sustained when prices crashed. Thus, some sort of dramatic restructuring of the Soviet Union was probably inevitable.

But although it was probably inevitable, the fall of the USSR also brought deep economic pain to both the post-Soviet republics and to other Eastern Bloc post-communist countries. The 90s were a terrible time for many of these nations, putting them in a hole from which it would take them years or even decades to recover. Seven years ago, Branko Milanovic wrote a post classifying post-communist countries according to who kept up and who fell behind.

I’d like to revisit that question seven years later, with some nicer graphs. I’ll include the two decades prior to the fall of the USSR, so we can compare the trends before and after. And I’ll also show a graph of percentage changes since 1990, so we can assess how much each country has caught up with Western Europe (the most obvious developed-country comparison). Data here is from the Maddison Project, though occasionally I’ll cross-check it against World Bank data.

The good news here is that things are generally looking better in the post-communist world than when Milanovic wrote his post. The bad news is that the basket cases are still basket cases, and it’s increasingly obvious why.

The Warsaw Pact countries

Eastern Bloc countries that weren’t part of the USSR have done quite well.

All of these countries were sort of flatlining in the decades before the fall of communism, losing ground against the West. They all experienced a negative shock when the USSR fell, but then resumed growing at faster rates than they had been under communism. Poland, Hungary, and the two countries comprising the former Czechoslovakia (Czechia and Slovakia) are on the cusp of developed-country status at this point.

In percentage terms, ALL of the Warsaw Pact countries have gained ground against West Europe since 1990, with Romania and Poland doing especially well:

This graph shows that all of the Warsaw Pact countries have caught up somewhat with Western Europe in percentage terms — even Albania, which went from 16% of West Europe’s GDP in 1990 to 28% in 2018. Romania and Poland have been especially impressive; Bulgaria a little less so, but still respectable.

World Bank data agrees closely with the Maddison Project here. Breaking out Czechia and Slovakia shows that the former is a true developed country now, with a per capita income of over $40,000 in 2019.

The former Warsaw Pact countries thus all should be regarded as post-communist success stories. Remember that all of these countries except Albania are now in the European Union, which helps their economic prospects a lot.

The former USSR, and Russia specifically

OK, now let’s look at the post-Soviet countries, and Russia in particular (since it’s the biggest by far and was dominant within the union).

We see the same pattern here as for the Warsaw Pact countries: Stagnation in the 70s and 80s, a dip after the fall of communism, and then a resumption of growth in the late 90s at a more rapid pace than before. But as the percentage graph shows, the USSR and Russia fell into an even deeper hole in 1991 than their Warsaw Pact allies did, and have done less catching up as a result:

In addition, Russia’s growth over the past two decades has looked far more uneven than that of the post-communist countries that joined the EU. It has suffered from volatile gas prices, then from Western sanctions following Putin’s annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Now let’s zoom in and look at the other post-Soviet regions.

The Baltics

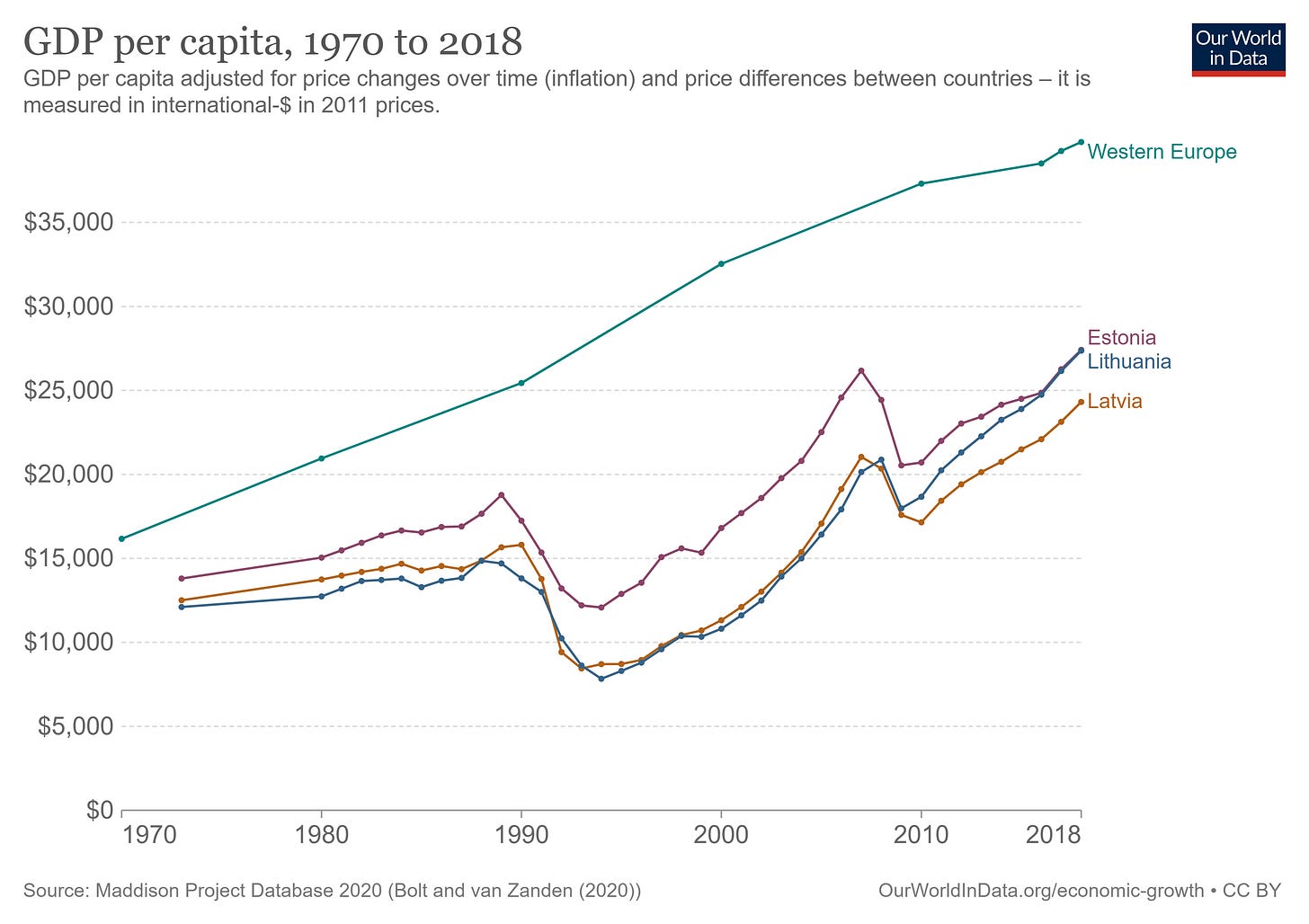

First let’s look at the Baltics, which, like most of the former Warsaw Pact countries, have joined the EU:

These countries were richer than the other parts of the USSR to start out with, but they took a huge hit from the fall of communism, and then suffered mightily in the financial crisis of 2008-10. As a result, though they’re all growing strongly and are all on the cusp of developed-country status, Estonia and Latvia haven’t really managed to make up ground against West Europe since 1990:

Lithuania, land of my ancestors, has done somewhat better than the other two (hehehe). But despite the lack of catch-up, Estonia and Latvia aren’t doing badly, as their income levels are pretty high and they’re now on a rapid growth trajectory (or at least were, before Covid). I’ll do a post about the Baltics’ interesting development model soon. But in general, I think these all have to be regarded as post-communist success stories. In fact, the World Bank has the Baltics doing even better, with essentially developed-country levels of income:

The Central Asian countries

The Central Asian countries are all natural resource exporters, and their fortunes have tended to rise and fall with natural resource prices. You can see they all took a hit from the fall of the USSR, but it’s pretty gentle, and probably corresponded to the economic weakness in their major trading partners combined with a major downturn in the global commodity cycle. After that they recover as resource prices recover and they develop new markets, but some recover much more than others:

This difference becomes even more apparent on the percentage graph:

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikstan are the laggards here, actually falling further behind the developed countries — probably due at least in part to political instability. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have done OK, making up the ground they lost during the resource slump. This kind of middling-to-disappointing performance is sadly typical for resource-dependent countries, and there are many reasons for it — Dutch Disease, uncompetitive wages, and the dysfunctional politics that accompany the Resource Curse. Kazakhstan is doing a bit better, though it started out a bit richer and its growth has slowed recently.

Turkmenistan, however, seems like the standout star here, with skyrocketing growth, rapid catch-up, and an almost developed-country level of income. But a word of caution here. Turkmenistan’s official data is highly suspect, and the World Bank shows much more modest performance (and for Uzbekistan as well):

So the conclusion here is:

It’s hard to be a natural resource economy, whether you’re part of a communist bloc or not.

Don’t trust data from small closed-off totalitarian states without a lot of cross-checking.

The Caucasus countries

Now let’s take a look at the Caucasus countries — Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. These countries have all been plagued by war in the post-Soviet era — Georgia fighting against two breakaway regions and then getting defeated by Russia in 2008, and Armenia and Azerbaijan fighting each other in 1994 and again in 2020. So perhaps it’s not surprising that their growth has been atrocious:

Even Azerbaijan’s burst of growth in the late 2000s was really just due to surging oil prices, and doesn’t look like a replicable phenomenon. In fact, looking at World Bank numbers makes Azerbaijan’s relatively rosy performance in the Maddison data look suspect:

In terms of catch-up, Georgia and Armenia haven’t made it out of the hole they fell into in the early 90s, and Azerbaijan only looks good because of that highly-suspect growth burst in the late 2000s:

The only real bright spot here is that both Armenia and Georgia look like they’ve accelerated recently, especially in the World Bank data. They’re not success stories yet, but if they keep things going they might eventually be.

The East European countries

Finally, we come to the East European post-Soviet countries — Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova. Frankly, none of these look great, though Belarus looks less bad than the other two:

And the same story holds when we look at the catch-up graph. Belarus is managing not to fall behind, but that’s about all it’s managing. Ukraine is falling behind West Europe, and barely treading water in terms of growth. And Moldova is growing so anemically, and took such a huge hit in the 90s, that it’s actually much poorer than it was before the USSR fell.

And I wish I could say the World Bank data give me reason for hope, but unfortunately they look exactly the same.

(Update: This is actually wrong! I missed it before, but the World Bank data for Moldova looks significantly better than the Maddison Project data!

Unfortunately Belarus and Ukraine look the same. I’ll try to track down the source of the discrepancy for Moldova.)

It’s worth mentioning that both Ukraine and Moldova have fallen afoul of Vladimir Putin, who has supported a breakaway region in the latter and actually gone to war against the former. As with Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan, post-Soviet “frozen conflicts” look like the big growth killer.

Putting it all together: The post-Soviet economic story

Looking at these graphs, and knowing what I know about the economic histories of these countries, I think I can put them mostly into four buckets instead of six:

1. Western-oriented industrializing success stories: These include most of the former Warsaw Pact countries and the three Baltics. They suffered from the fall of the USSR, but they got their industrialization back on track, joined the EU, largely maintained political stability and peace, and are now catching up with the developed countries (as basic economic theory would predict).

2. Central Asian resource economies: These have muddled along much as resource-based economies tend to do.

3. Russia and Belarus: Russia is its own strange hybrid of still-dysfunctional but often high-tech manufacturing economy and Central Asian resource economy, while Belarus is basically a satellite state of Russia whose fortunes rise and fall with Russia’s.

4. Frozen-conflict countries: Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Moldova all suffer from breakaway regions and/or military conflicts, either with each other or with Russia. This has prevented them from joining the EU (which is often Putin’s reason for supporting the breakaway regions and prosecuting the wars), which in turn has prevented them from getting on the fast track to industrialization like their luckier Baltic and Warsaw Pact counterparts. It also tends to cause political instability, as the people of these countries fight over how to best prosecute their conflicts.

With the benefit of seven more years of hindsight, we see that Milanovic’s verdict was prematurely pessimistic — freed from the shackles of communism, countries that aren’t dependent on natural resources have generally tended to converge with the West. But for a handful of unlucky countries, unresolved post-Soviet territorial conflicts and the malign influence of the fearsome Vladimir Putin have prevented them from achieving their economic potential.

The lesson, then, seems clear: The post-communist world won’t be an unambiguous success story until the frozen conflicts are resolved and Russian power becomes a more benign force in the region.

Czhech Republic and Poland felt first world, Hungary felt second world. Just from my brief visits there in early 2020

Seems like a priority for the EU should be to push back against anti-liberal politics in Poland and Hungary, and reward good leaders in Ukraine and Moldova with membership. Then down the line expand to Belarus/Georgia/Armenia and even Russia when Putin & Lukashenko eventually lose power or die. Despite the animosity that’s played up these days, it seems to me that all these European countries should converge economically, no?