Housing and wealth-building

Young people need wealth. Poor people need wealth. How can we get it to them?

The other day I wrote a post suggesting a Singapore-style plan for public housing, in which the government builds new housing and sells it to young people and poor people at discount prices. Matt Yglesias wasn’t convinced. If we want more housing, he said, just let the private sector build more:

The cause of [the] housing shortage is not obscure: it’s generally illegal to build denser housing on expensive land in high-cost cities, especially in their rich neighborhoods and doubly-especially in the suburbs. If we change those rules, housing will become less scarce…we should dramatically roll back regulatory barriers (zoning rules but also parking rules, etc.) to new privately built housing.

Sure. That’s an important thing to do. And as both Matt and I note in our posts, deregulating housing is a necessary first step to doing anything like what Singapore did. State and local governments would need to change their own rules in order to be able to build housing themselves — and if you have the political will to change the rules for yourself, you can change it for private developers too.

So yes, change the rules. Allow more housing. It’s a necessary thing. (I think Matt is a little optimistic that it’s a sufficient thing — as housing activist Brian Hanlon points out, government housing construction is special because you at least theoretically can do it during recessions. That could allow it to avoid the well-known boom-and-bust cycle that plagues privately built housing, as well as serving as a shovel-ready fiscal stimulus project in bad times. Of course, politically that’s easier said than done.)

But anyway, the Singapore-style build-and-sell plan that I was envisioning is not just a way to increase housing supply. It’s a way to build middle-class wealth.

Americans need more wealth

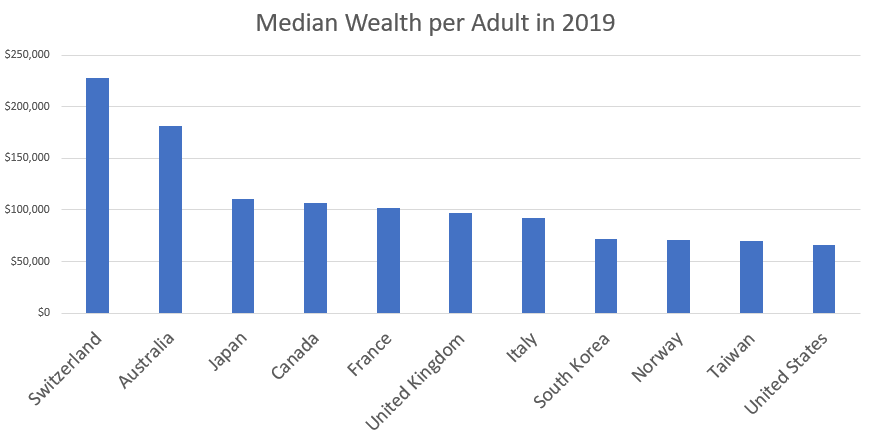

The typical American doesn’t have much wealth. According to Credit Suisse’s Global Wealth Databook, the U.S. ranks third in average wealth but only 22nd in median wealth per adult. Here’s us compared with some of our peers:

Do we really think it’s OK that the typical American has a lower net worth than the typical Korean, Italian, French, Japanese, or Canadian person? Should Australians really be almost three times as rich as Americans?

Now, a small amount of this is an age difference; the median American is younger than the median person in most of these countries, and building up wealth takes time. But isn’t it OK to shift the distribution of wealth so that young people have a bit more? That would certainly help with affordable family formation, and I know Matt is a pro-natalist.

But anyway, age is only a small piece of this. A lot is inequality. So let’s think about how we might get more wealth into the hands of the typical American.

The typical American’s wealth is in housing

First let’s think about the type of wealth that the typical American owns. Yes, 401(k)’s and IRAs and savings accounts exist. But stocks and bonds are mostly a rich-people thing. As economist Edward Wolff has pointed out, middle-class people’s wealth is mostly in real estate. Specifically, in their own home.

Now, in the past, a home was a pretty good way to build wealth — not just in the U.S., but in many rich countries. In a 2015 paper, Jordà et al. found that over the very long haul, housing has done as well as or better than stocks in terms of average returns, while also being less volatile. Even over the last 35 years, housing has done almost as well as equity (note that this includes both rental yield and price appreciation):

Why? The obvious reason is agglomeration and clustering effects. What does that mean? It means that cities keep on becoming more valuable places to live, as companies and workers find ever more reasons to clump together in close proximity. As people and companies keep piling into cities, the value of land goes up.

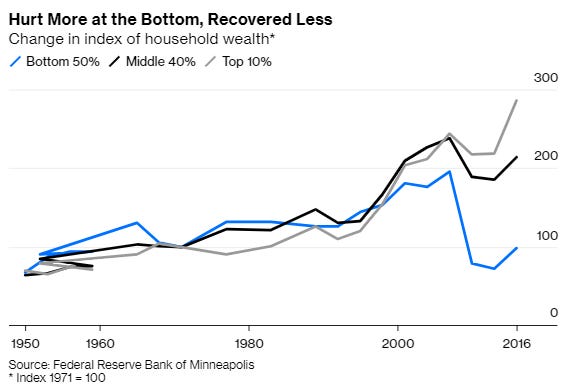

That has been a pretty damn good deal for middle-class wealth! But in 2007-8, of course, it all came crashing down. Housing took a big and lasting hit, while stocks took only a small and temporary hit. That’s why middle-class American wealth, which had been on a pretty smooth upward trajectory since the end of World War 2, took a huge hit in the financial crisis:

I think that over a decade later, the American commentariat has still failed to process what a tremendous blow the American Dream took in 2007-8.

So how are we going to restore that dream? How are normal Americans going to get their wealth back on track?

Various ideas for middle-class wealth building

1) “Suck it up and save it back”

The most obvious way to get middle-class people more wealth is for them to just save more of their income . This is, in effect, what we have told people to do since housing crashed. And it’s how Japanese people got all that wealth (though they don’t save much these days).

But saving back the American Dream is going to be a long and arduous process. The years between 2013 and 2019 were good years, and incomes grew, and savings rates were OK. But as COVID shows, there will always be another recession, and even with good monetary and fiscal policy to ensure full employment (hah!) it would take a long time to rebuild what was lost in 2007-8. Meanwhile the rich sailed through the crisis with their stock portfolios intact, and companies scooped up much of the distressed housing that regular people had to sell off in the crisis. “Save it back” is a bit of a tough sell, policy-wise.

2) Give people more income to save

An obvious alternative is to simply tax the rich (perhaps with a wealth tax) and give that money to everyone else (perhaps with a UBI). But wealth taxes have failed to raise much revenue in the European countries that have tried them; rich people are pretty good at avoiding them. And UBI is a tough sell politically. Furthermore, this approach also requires people to build wealth out of savings.

This isn’t a bad idea, but it’s a logistically and politically difficult one, that won’t necessarily restore the feeling of the American Dream.

3) Social wealth funds

This idea would basically have the government do people’s savings for them. The advantage of this is that it doesn’t rely on people to save their own money. The disadvantage is that it does this by basically locking up people’s wealth and doling it out to them as income. Wealth that people can’t sell off might be “better” for them in a sort of paternalistic sense, but it probably doesn’t feel quite like wealth that you fully control. So while this is a cool idea and worth a try, I’m not sure it will be as satisfying as the kind of wealth middle-class people had before the financial crisis

And that leaves one big idea left: Housing. I.e., the way we used to do middle-class wealth.

Housing as a financial asset

Owner-occupied housing as a financial asset leaves much to be desired. For one thing, it can easily turn into a zero-sum game between the generations — for old people to make a return on their housing, they have to sell it off to younger people at a big markup. That’s not actually a Ponzi scheme — since the economy keeps growing and agglomeration/clustering keeps making land more desirable, you actually can have each generation build wealth this way. The problem is, the older generation has an incentive to use their political power to limit the supply of housing in order to jack up the price of their own homes even more than the natural growth of cities would imply. And this forces young people to either rent forever, or allow the olds to extract more of their wealth.

Meanwhile, the restrictions on housing supply hurt the economy, because they make it harder for people to live and work in the most productive cities. This is the well-known NIMBY dynamic that is choking the San Francisco Bay Area to death. Japan, where houses depreciate over time because the government periodically knocks them down to build new stuff, happens to be one of the very few countries whose big cities have actually built enough housing to keep rents from rising in recent decades.

Another downside of housing is that it’s un-diversified. If your city has a local downturn (like when the auto industry fled Detroit), you can lose both your job AND your nest egg at the same time, which really sucks. Owner-occupied housing also isn’t very liquid — it’s tough to sell, and moving disrupts your life a lot.

But there are advantages to housing as a financial asset. First of all, normal people can probably understand housing markets a lot better than they understand stock markets. Basically, normal people do a crappy job of picking stocks and timing the market. So they end up either losing money trying to invest for themselves, or paying exorbitant fees to money managers or 401(k) plan managers or a host of other middlemen that end up siphoning away much of their life’s savings. But most people don’t try to flip their own house like they would flip a stock. And because they actually live in their house, they tend to try to buy a house with good intrinsic long-term value, rather than gambling on what seems like a hot commodity.

Second, owning a home nudges people to save more money than they otherwise would have. One thing we know from behavioral economics is that savings rates are HIGHLY susceptible to nudges. A monthly mortgage payment feels like paying rent, but in fact you’re saving money! So having a mortgage takes some of the spending that would otherwise go to consumption (via rent), and redirects it toward savings. (It also nudges middle-class people into an asset class with higher risk and higher expected return, which can be bad in cases like 2007-8, but also allows them to keep up with the rich in the long term.)

Finally, as noted above, housing is just the kind of investment that the American middle class is used to. We could change our culture and our financial system to make Americans save a ton of their income into bonds (like Japanese people used to do) or stocks (through low-fee diversified vehicles like Vanguard or Betterment provide), while housing depreciates like it does in Japan. But do we really think we can pull off this transformation? Maybe we can, but it’s worth considering the alternative — tweaking our housing system so that it builds wealth for the vast majority of every generation.

Sustainable housing wealth growth

Unless cities become much less attractive places to live and work (perhaps due to the rise of truly remote work?), the value of urban land will continue to grow. If all we do is allow the private sector to build lots of housing whenever and wherever it wants, that means each generation will get some piece of that growth. So that’s one order of business — make it easy to build new housing. The YIMBY solution.

But there are better ways to get that wealth into young people’s hands sooner, and make the distribution more equal. A simple one would be down-payment assistance. Both Elizabeth Warren and incoming Vice President Kamala Harris have proposed such a program specifically for Black people excluded by redlining, as a way of closing the racial wealth gap. But you could also do it for low-income people in general, or for young first-time homebuyers (probably with some fade-out for high earners).

The thing is, unless you do the YIMBY solution in a whole lot of places, a down-payment assistance program is going to pump up the prices of existing housing (at taxpayer expense, no less). With inelastic supply, an increase in demand just raises price, as we saw when cheap subsidized student loans pumped up college tuition. That’s not really good for anyone, since it basically means you’re taxing productive labor and capital to hand money to existing (old) homeowners. And since YIMBY stuff tends to happen at the state and local level whereas down-payment assistance would be a federal program, it will be very hard for the federal government to make sure that everywhere is building enough new supply so that the down-payment assistance enriches the people it’s supposed to enrich. (Maybe you could make down-payment assistance conditional on whether a city or state builds sufficient quantities of housing. It’s worth thinking about.)

In fact, America successfully pulled off a version of the YIMBY-plus-down-payment-assistance thing, back when we built the suburbs and gave veterans money to buy the newly built homes via the G.I. Bill. But the political barriers facing housing construction now are much more formidable than back then.

So that’s where the Singapore-style program comes in. Government building houses cheaply and selling them at or below cost to low-income and first-time homebuyers would accomplish much the same thing as YIMBY-plus-down-payment-assistance. Because it would both build new housing and help people buy it. But because the same entity — a state or local government — would be A) lowering legal barriers to construction and B) subsidizing the purchases of that housing for the people who need to start building wealth, it would make sure that the two aren’t mismatched in space and time.

In other words, a Singapore-style housing program is really about redistributing land wealth — it’s a Georgist program. The expansion of supply and the subsidization of purchases for low-income and first-time buyers both redistribute land rents from those who already have a lot of housing wealth to those who start out with little or none.

Of course, if the program were subsidized from general revenue (in order to increase the discounts for buyers), it would represent a transfer from high-earners’ labor income to middle-class housing wealth. Economically speaking, that’s not the most efficient thing in the world. But the benefit in terms of equalizing America’s incredibly unequal wealth distribution might outweigh that by a lot.

So that’s the real purpose of a Singapore-style housing program — to redistribute land wealth throughout the populace, and thereby restore the American Dream. Maybe there are better ideas for doing this. I’m certainly open to them! But this is one idea.

Update: Jenny Schuetz has a pretty persuasive post arguing against

By the way, remember that if you like this blog, you can subscribe here! There’s a free email list and a paid subscription too!

"Of course, if the program were subsidized from general revenue (in order to increase the discounts for buyers), it would represent a transfer from high-earners’ labor income to middle-class housing wealth. "

Sounds like a bit of equalizing of the upper/lower middle class divide you mentioned in a previous post?

Why should housing be a way to build wealth? I mean, people use it but it seems like a terrible idea. Housing needs constant investment to maintain and build its value. Increases in value are taxed immediately without liquidation through property taxes in most states. Tax perks for owning it decrease over time and are generally setup so that the wealthiest benefit the most.

It also made a lot more sense in a society where people started working at a company shortly after graduating school (high school or college) and worked there their whole careers. In an environment where you might change jobs regularly, then being bound to location decreases economic potential.

If you are wanting to build wealth, why not simply do a baby bond? Give every child 5k to 10k in treasury bonds (or even better a total market index fund). They can take out half the money when they turn 25 and the rest sometime later.