My home state of Texas is now plurality Hispanic:

Given all the hand-wringing about a “Great Replacement”, it’s astonishing how much of a non-event this has been. Texas is still a deep red state. Texas Hispanics still lean toward the Dems, but they shifted strongly toward Trump in 2020, and Republicans in the state still reliably get 40% of the Hispanic vote. Meanwhile, Texas’ culture, which always had very large Mexican influences, has not noticeably changed as a result of the influx.

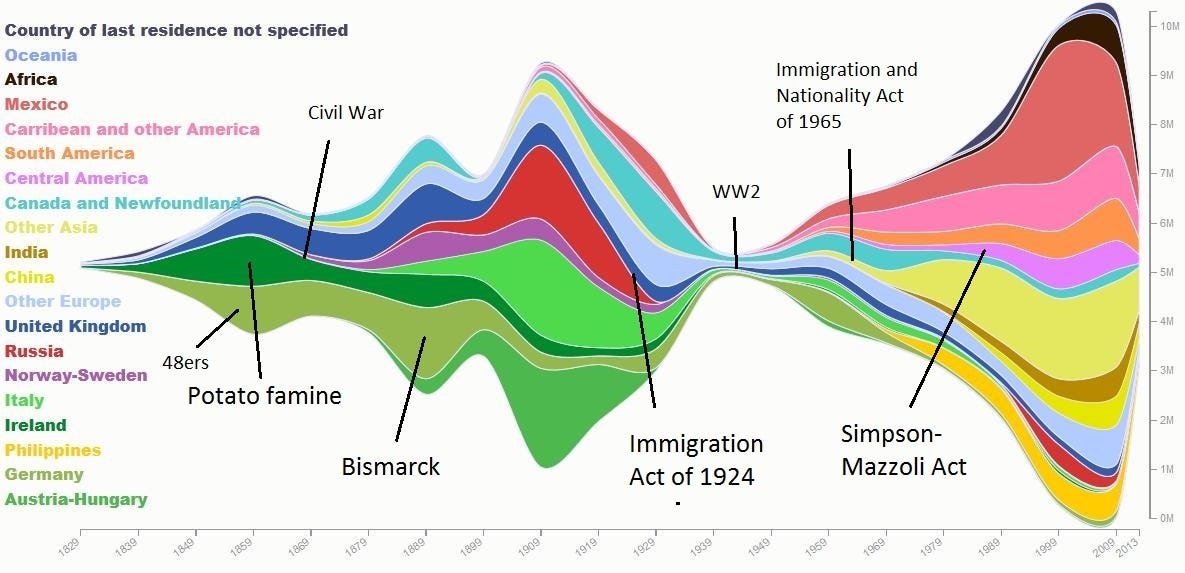

This reinforces my thesis that the best historical analogy for Hispanic immigration to the U.S. is the great Irish immigration of the 1800s. The usual analogy we draw is to the Italians, but I think the Irish make a better model. First of all, Irish immigration, like immigration from Mexico and Central America — but unlike immigration from Italy — was very drawn-out over a long period of time:

Like Hispanics, Irish migrants were mostly working-class folks who came for mainly economic reasons — pressures from poverty back in Ireland, plus the great dream of making it in America. And like Hispanics, they provoked a sustained and ferocious pushback from nativists.

All the same worries

The cartoon at the top of this post is from 1871, and features a huge number of negative stereotypes — the Irish as terrorists, as drunkards, as criminals, as seeking to dominate American culture.

Worries about the Irish often particularly focused on the religious angle — the idea that as Catholics, Irish people were beholden to the Pope and would either subvert and destroy American democratic freedoms, or literally massacre Protestants. Vicious pogroms against the Irish broke out in the early 1800s. But here are a couple of screenshotted passages from John Higham’s Strangers in the Land, showing that anxiety over race war and genocide between Catholics and Protestants persisted at least into the 1890s:

You can see these anxieties paralleled in modern conservative worries about Hispanic immigration. Conservatives worry that terrorists are coming up through the southern border, that traditional American culture will be destroyed by immigrant culture, or even that the U.S. will have a civil war along racial lines.

Economic concerns are also very similar. Read Hidetaka Hirota’s book Expelling the Poor for a good overview of how this played out in the early 1800s. Worries that poor Irish immigrants would swamp local welfare systems — similar to worries about Hispanics overloading the welfare state in the 1990s and beyond — resulted in a large number of restrictive anti-immigration measures at the state level. These largely failed, since Irish immigrants would usually find a way to enter via a different state, but they show that the U.S. was never a country of open borders.

On top of this were political worries. Since Irish immigrants usually voted for the Democrats, Federalist and Whig politicians were worried that they were being politically replaced. Here are a couple of screenshotted passages from Daniel Tichenor’s Dividing Lines:

These are exactly the same as the modern GOP’s worries that the Democrats are importing Hispanic votes through lax immigration policies:

[Tucker] Carlson wailed that the Democratic Party was “trying to replace the current electorate” in the U.S. with “new people, more obedient voters from the Third World.” That, according to Carlson, is “what’s happening actually. Let’s just say it. That’s true.”…

“Every time they import a new voter, I become disenfranchised as a current voter,” he continued. “I have less political power because they are importing a brand new electorate.”

Those worries aren’t entirely unfounded — until recently, some Democrats were vocal about their hope that immigration would deliver them a long-lasting electoral majority, and many still probably privately harbor the same hope.

(Side note: It’s kind of interesting that the Democratic party, despite its total reversal on race and economics over the centuries, has remained the party of immigrants throughout all of American history.)

So every one of the worries about Hispanic immigrants in the modern day, whether justified or unjustified, has clear parallels in worries about Irish immigration in the 1800s. But the similarities don’t stop there. When I look at how Hispanics are actually integrating into American society, I see a similar process of assimilation, upward mobility, and political normalization.

Following a similar path

When the Irish arrived on American shores, they generally had very little money, simply because Ireland was a very poor country at the time (you can read some of the statistics in Expelling the Poor). But over time, Irish Americans climbed the economic ladder, and ultimately became more or less indistinguishable from other White Americans. There has been concern that Hispanics would not follow the same pattern, and would languish as a racialized economic underclass forever.

Luckily, those worries are proving unfounded. Chetty et al. (2018) found that once you control for the composition effect from continued immigration, Hispanic incomes are converging with White incomes at a steady rate:

We study the sources of racial and ethnic disparities in income using de-identified longitudinal data covering nearly the entire U.S. population from 1989-2015….[T]he intergenerational persistence of disparities varies substantially across racial groups. For example, Hispanic Americans are moving up significantly in the income distribution across generations because they have relatively high rates of intergenerational income mobility…

Hispanic Americans are moving up significantly in the income distribution across generations. For example, a model of intergenerational mobility analogous to Becker and Tomes (1979) predicts that the gap will shrink from the 22 percentile difference between Hispanic and white parents observed in our sample…to 6 percentiles in steady state…

Hispanics are on an upward trajectory across generations and may close most of the gap between their incomes and those of whites…Their low levels of income at present thus appear to be primarily due to transitory factors.

And in a 2022 Noahpinion interview, economist Leah Boustan, author of the excellent book Streets of Gold, reported strong upward mobility even for the descendants of poor Mexican immigrants:

We find that Mexican immigrants and their children achieve a substantial amount of integration, both economically and culturally. First, on the economic side, we compare the children of Mexican-born parents who were raised at the 25th percentile of the income distribution -- that's like two parents working full time, both earning in the minimum wage -- to the children of US-born parents or parents from other countries of origin. The children of Mexican parents do pretty well! Even though they were raised at the 25th percentile in childhood, they reach the 50th percentile in adulthood on average. Compare that to the children of US-born parents raised at the same point, who only reach the 46th percentile….[T]he second generation is doing substantially better than the first -- and that's important progress.

Qualitative research by sociologists finds a similar picture unfolding at the ground level. Surveys of Hispanic Americans themselves find the same. And the picture is reinforced by recent trends. In the 2010s, Hispanic income grew faster in percentage terms than White, Black, or Asian incomes:

And Hispanic outperformance appears to be continuing into the 2020s:

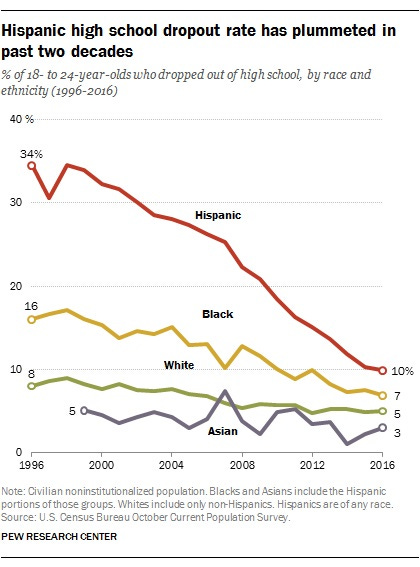

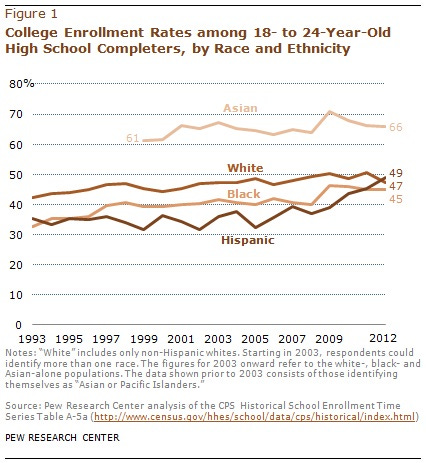

This income catch-up is being driven by several factors. Geographic dispersal from the Southwest and Florida to the rest of the country is one factor. Education is another. Hispanic education attainment has risen strongly — dropout rates have plummeted, and college enrollment has soared.

Hispanics are also beginning to catch up in terms of wealth. This takes a lot longer than catch-up in income, of course, since A) it takes a long time to save money, and B) the the need to support poor immigrant parents slows down wealth accumulation. But the gap is starting to close:

One big driver of this is the rise in Hispanic homeownership rates:

[T]he Hispanic homeownership rate reached 48.6% in 2022, the eighth consecutive year of growth…Latinos added a net total of 349,000 homeowner households last year, which is one of the largest single year gains over the last decade…Latinos trend younger as homeowners. About 70.6% Latinos who purchased a home with a mortgage in 2021 were under the age of 45, compared to 63.9% of the general population, and 61.5% of non-Hispanic White buyers…Texas has consistently topped the list for most Latino net migration, best opportunity markets and producing the greatest number of new Latino homeowners.

So on economics, Hispanics are treading the same path as the Irish.

What about culture? This is much more nebulous, as perceptions of cultural difference and assimilation are strongly subjective, and there is no agreed-upon criterion. Boustan did find an interesting measure — the names that immigrants pick for their children. And here, for Mexican immigrants at least, she finds that assimilation is rapid:

On the cultural side, we already talked about some of the metrics we use to assess whether immigrants are fitting in. Some people worry these days that Mexican immigrants hold themselves apart - that they are more likely to live in Spanish-speaking enclaves, etc. But we find that Mexican immigrants are actually the group that experiences the fastest assimilation, as measured by the names that they pick for their children. So, Mexican immigrants are certainly trying to become American to the same degree (if not more!) than other groups.

Language is one big difference between the Irish and the Hispanics, since the former came over already speaking English. But evidence consistently finds that Hispanics adopt English very quickly. And by the 3rd generation, a majority have left the Spanish language behind.

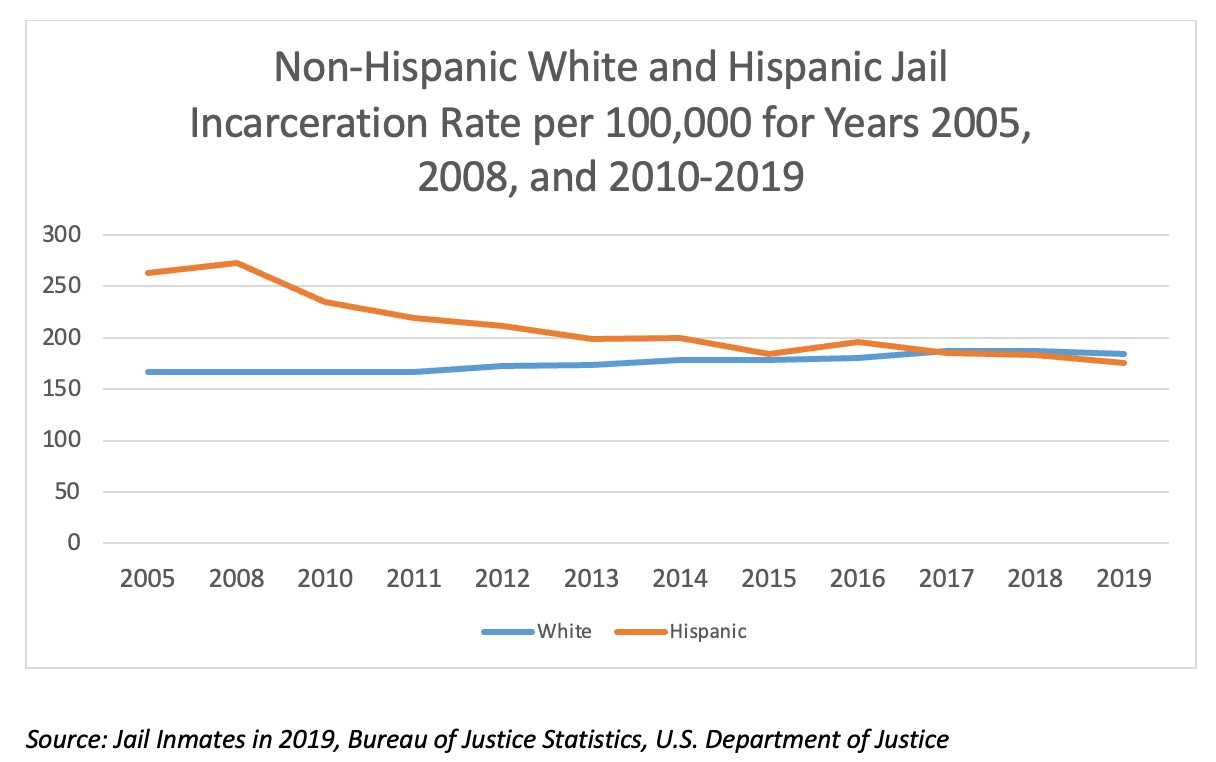

The stereotype that Hispanics commit more crimes than the native-born population was never true, once you controlled for the age of the population. But in recent years, even without controlling for age differences, Hispanic jail incarceration rates have fallen to the Non-Hispanic White average:

In fact, as Keith Humphreys notes, rather than joining the ranks of the incarcerated, Hispanics are overwhelmingly joining…the police.

From 1997 to 2016…the proportion who were Hispanic increased 61%. This helps explain why a June 2021 Gallup poll found that the proportion of Hispanics expressing “a lot” or “a great deal” of trust in police was 49%, almost as high as whites (56%), and far greater than that of African-Americans (27%).

This all strongly echoes the pattern of the Irish, who were initially stereotyped as criminals, but who joined police forces in large numbers (this is probably where the term “paddy wagon” comes from). Police forces around the country still have a strong Irish American presence to this day.

And of course the final measure of assimilation is political. The recent shift of Hispanics toward the GOP is modest, but it suggests that Hispanic Americans will eventually be pretty evenly split between the parties. Even the 60-40 split that currently exists is very far from racial bloc voting.

So in every way that I can see, Hispanics are following the path that took the Irish from stigmatized, feared working-class immigrants to highly integrated middle-class Americans. That doesn’t mean the great Hispanic immigration wave will leave America unchanged — assimilation is a two-way street, and Irish immigration certainly left a strong mark on our country. But I expect that the historians of the future will write about the great Hispanic immigration wave much as the historians of the present write about the Irish.

Update: Here’s some more data from Keith Humphreys about Hispanic Americans’ experience with the criminal justice system, which now looks very similar to the White average.

I've lived for many years in two cities where I encountered Hispanic immigrants. Both experiences cemented my great respect for immigrants.

In the 70s in New York City, I worked with Dominican kitchen help in my job as a waitress. Most of the time I was the only person in the restaurant who could interact with the kitchen help in Spanish. I also interacted with many Spanish speaking immigrants during my five years as a receptionist. My impression was that they were strangers in a strange land struggling hard to figure things out.

When I arrived in Houston, the situation was very different. Here, the border with Mexico has been porous for centuries. There are Tejanos in Texas whose ancestors lived here for centuries before Esteban Austin (that's Stephen to you) Arrived on the scene. Thus, there is a whole matrix of Hispanic culture into which new arrivals fit seamlessly. They have all kinds of formal and informal support systems to facilitate their integration into the economy whether their participation is strictly legal or not. They don't have to depend on a woman with one year of college Spanish to act as their interpreter, as the New York immigrants did when I was a receptionist.

I’m thinking of writing an article about this (have a draft saved, just need to flesh it out adequately) about how the usual suspects (guilt ridden whites + various “POC” hoping for their acceptance and aggrieved blacks, both fixated on “oppression”) are trying to replace a dying white monoculture with not an emerging multicultural society but a system of ethnic competition mediated through political, economic and cultural institutions. I’d rather we not end up with a Lebanon/Fiji style conflict, but if we do I’ll ensure my “people” get theirs.

My hope was that Asian and Hispanic immigrants would be a large enough bloc to disrupt the racial pathologies on both sides - on the right, a yearning for a homogenous white monoculture and on the left the melding of white guilt and black grievance demanding ever more special privileges. This article has given me some pause. We may still avoid replacing a monoculture with racial composition and moving to true multiculturalism, but I’m not sure how.