Elizabeth Warren has introduced a bill that would attempt to limit “price gouging”, by imposing price controls in cases of “exceptional market shock”. This bill has generated a large amount of highly contentious public debate. So far I’ve held back from writing about this, since A) other people have written a lot of good stuff that covers most of it, and B) I said much of what I wanted to say about price controls back in this post in January:

But since so many people are talking about this, I figured the public could use some help in sorting out the debate.

There are really three questions here:

Is corporate greed contributing to inflation?

Is market power contributing to inflation?

Are price controls a good way of addressing market power and/or inflation?

So let’s go through each of these questions.

Greedflation is not a thing, and nobody really thinks it is

Elizabeth Warren and the people pushing price controls don’t really believe that a sudden surge in corporate greed is responsible for our recent surge of inflation. But their rhetoric can sometimes give the impression that they do believe this:

I poked fun at this rhetoric by creating the following (sarcastic) chart:

Catherine Rampell has an excellent column in which she makes a lengthier, more detailed version of the same argument.

The reason it would be silly to blame inflation on greed is that companies are always greedy; if they could have raised prices this much back in 2019, they could have. Thus, corporate greed is a constant; inflation is not. There’s no chance of dealing with inflation by hectoring companies to want profits less.

As I said, progressives know this. Unfortunately, some appear to think that rhetoric implying this “greedflation” story will be good populist politics and get people riled up at corporations. Rampell writes:

I’ve been scolded before, including by White House senior aides, for making a fuss about Democrats’ demagoguery on this issue. So what if Biden and Democratic lawmakers want to grandstand about corporate greed? Who cares whether Biden asks for another gratuitous investigation into whether “illegal” conduct is driving up gas prices? This kind of populist anti-corporate rhetoric polls well, they say. It does no harm. It’s just cheap talk, so Democrats can show they’re Doing Something about inflation.

But such allegedly cheap talk has become very expensive…it is encouraging Democrats to pursue policies that could be actively harmful. These include a proposed tax on “windfall” oil profits, which would likely reduce oil production exactly when we want output to increase.

Rampell is right. Even if it rousing anti-corporate sentiment were good for Democrats’ electoral prospects (which I highly doubt), it pushes Democrats’ governance toward questionable policies. Lashing out at corporations by any means available will not bring down inflation, and voters in November are still going to be mad.

But underneath the layer of overheated and probably-unhelpful rhetoric, there is the core of an interesting economic argument. Though greed isn’t driving inflation, there is a chance that monopoly power is making it worse.

Price gouging is sort of real, but it’s not so simple

The non-ridiculous version of the “greedflation” story is the idea that monopoly power is exacerbating inflation. When politicians like Elizabeth Warren say “greed”, maybe they’re just using that word as a rhetorical stand-in for “monopoly power”, since the latter is a term that few people know and even fewer understand.

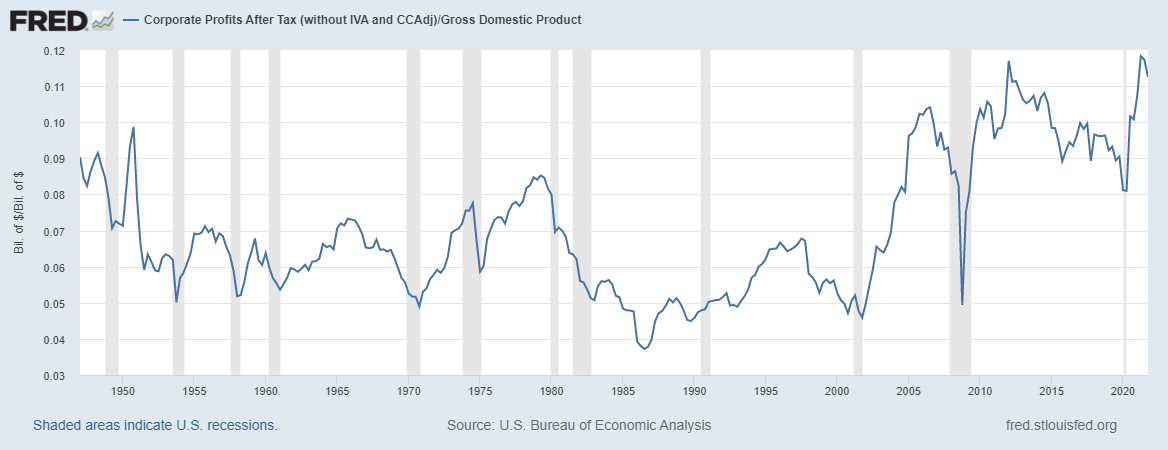

In a perfectly competitive economy, companies don’t make profits (except what’s needed to pay back their cost of capital). But in the real world, companies make quite a lot of profit. In fact, since the early 2000s, profits have risen as a share of the economy:

Economists argue back and forth over why this happened. I won’t go over that whole debate here, and it’s not yet resolved. But some economists believe that the reason profits have risen is that companies have more market power now than they did two decades ago. Suffice it to say that this explanation is fairly plausible.

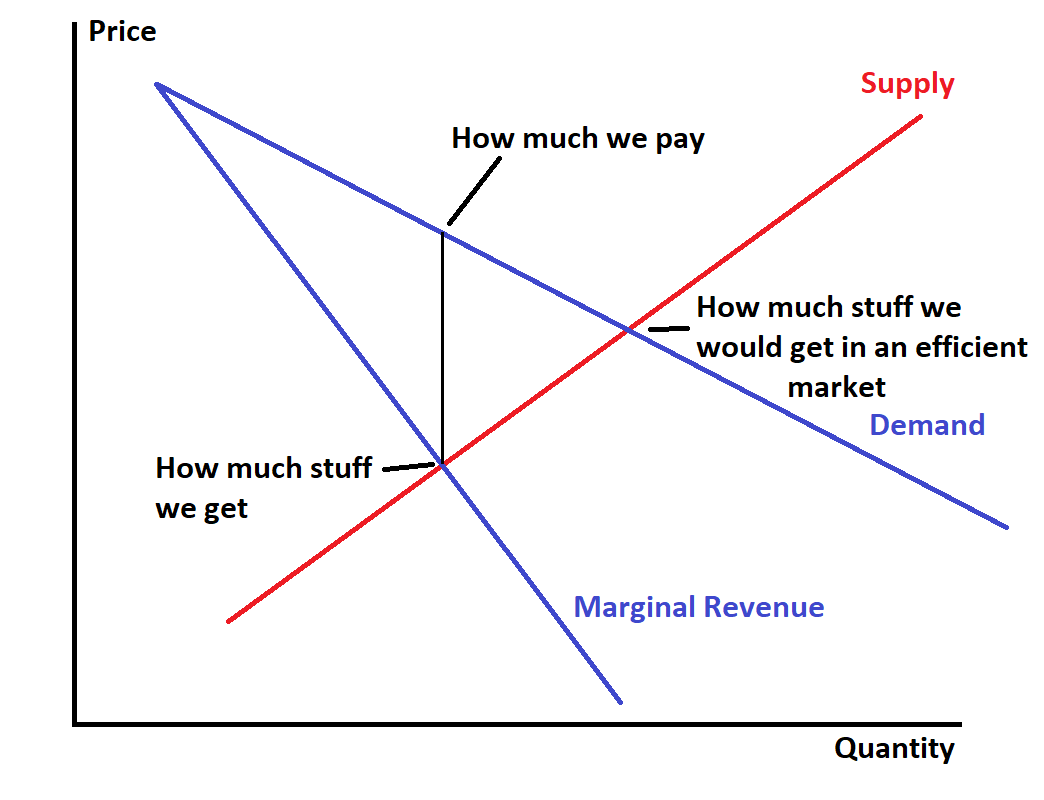

When companies have monopoly power, they raise prices beyond what those prices would be in a competitive market. And they do this by holding back output in order to make goods artificially scarce, thus increasing the price. So with monopoly power, we get a less efficient economy than we would otherwise. Shareholders make out like bandits, but we the consumers pay too much and get too little.

Here’s a picture of a simple, Econ 101 model of a total monopoly. Of course in the real world, companies aren’t total monopolies, at least in America; the truth lies somewhere in between perfect competition and perfect monopoly. But this simple model shows the basic idea of why monopoly power raises prices and lowers output.

So if something like this is going on in the modern American economy, we can raise economic efficiency — meaning lower prices and higher GDP — with better antitrust. It can also provide a rationale for price controls (which I’ll talk about in the next section).

OK, so far so good. Now let’s think about inflation, and how monopoly power might affect that.

First of all, there could be an increase in monopoly power in the economy. That would increase prices, and also increase profits. In the graph of profits shown above, we see that there is a jump in the share of profits as a share of the economy after the pandemic. Did powerful companies get more powerful as a result of their competitors getting wiped out by the Covid shock?

Maybe. But we also see that this jump in profit’s share of the economy is only about the same size as the jump after the Great Recession, at which time inflation was low. The big increases in profit as a share of GDP happened in the early 2000s, when inflation was also low. So it doesn’t seem likely that an increase in monopoly power since early 2020 is likely to be a big part of the inflation story. Also, for this story to fit, we’d probably have to see continuing increases in monopoly power in 2021 and 2022, which doesn’t make sense with the pandemic story. And finally, economists who study monopoly power don’t see much of an increase since Covid.

So we can probably discard the “monopoly power went up” explanation for inflation.

But in fact, Elizabeth Warren and other advocates of the “greedflation” story probably don’t have that story in mind when they accuse companies of price gouging. Instead, they probably believe that companies are using their existing level of monopoly power to take advantage of the current economic situation in order to raise their prices (and profits) more than they would in a competitive market. For example, here’s a thread by Lindsay Owens of the Roosevelt Institute that basically makes this case:

To evaluate this, we first have to think about two competing explanations for the current inflation:

Inflation might be caused be a negative aggregate supply shock, from supply chain snarls, China lockdowns, and the war in Ukraine.

Inflation might be caused by a positive aggregate demand shock, from Covid relief spending and easy monetary policy in 2021.

(There’s also the hybrid theory, which is that inflation was caused mostly by Covid relief spending back in 2021, but that now in 2022 it’s being caused by China lockdowns and the Ukraine war.)

If you think inflation is being caused by a negative supply shock, then the “greedflation” story just doesn’t make sense at all. Yes, higher costs for companies will raise prices. But it will also reduce profits. When companies with monopoly power see their costs go up, they do manage to pass on a lot of the cost increases to their consumers, but they also take some of the hit themselves. So the idea that companies would be exploiting a supply shortage in order to make record profits just doesn’t make a lot of sense.

In other words, in order to accept the “greedflation” story, you also have to accept that the fundamental impetus for inflation came from government largesse.

But anyway, that might be true. (And indeed, I do think it’s the likeliest story, at least for 2021.) So if there’s a positive shock to aggregate demand, will monopoly power exacerbate inflation?

The answer is: Maybe. It could go either way. As this blog post demonstrates, depending on the slopes of the various curves, it’s possible that monopoly power could work in the opposite direction, dampening the impact of a demand shock on prices, even as profits increase. But as John Quiggin and Flavio Menezes show, it’s also possible for monopoly power to exacerbate the inflationary impact of a demand shock.

And that’s just in the simplest possible theory. There’s no guarantee that the macroeconomy works according to a simple model; more complex stuff like expectations could also be playing a role in inflation, for example. Update: Paul Krugman has a thread in which he discusses another possible theory, based on price-setting norms.)

In other words, one version of the “greedflation” story might possibly be true. It goes like this: Biden and the Democrats spent a bunch of money in 2021 to help people recover financially from Covid, and to help the economy recover more quickly. And the Fed kept interest rates really low and lent out a lot of money, in order to speed the recovery. This succeeded, but because of their dominant market position, some big businesses captured way too much of that government spending and lending, pocketing profits by raising prices and causing inflation in the process.

Now the next question is: If you believe that story, what is the proper response?

Price controls: Dangerous in theory, even more dangerous in practice

In my post back in January, I went over why I think price controls are a bad tool for fighting inflation, even with monopoly power. But let me quickly recap.

If there’s monopoly power in the economy, then a price ceiling can actually raise GDP. But if the ceiling is set too low, it backfires and causes shortages. The model looks like this:

(This is similar to the way minimum wage works, except in that case it’s about monopsony power rather than monopoly power.)

But although price controls can potentially reduce prices, this doesn’t mean they slow inflation. This is a difficult but important distinction to understand. It’s all about the level of prices vs. the rate of change. Here’s what I wrote in my earlier post:

Notice that in the monopoly model, the price ceiling doesn’t actually change the supply curve. So if the aggregate supply curve just comes from some sort of summation of companies’ individual supply curves, price controls aren’t going to change the aggregate supply curve either.

Because remember, even if there are monopolies in each market, that doesn’t mean the macroeconomy overall acts like a monopolized market. There’s no one company that has a monopoly over aggregate production. So price controls, macroeconomically, are likely to reduce inflation only at the cost of causing a recession:

That would be a bad idea; sure, we’d beat inflation, but we’d throw a ton of people out of work. If that’s what we want to do, we might as well use monetary policy.

In other words, price controls are how you get gas lines like the ones in the 1970s. If you want to enrage the American populace, and make them vote Republican, I can think of few better ways to do that than to create huge gas lines.

And as I explain in my earlier post, it’s possible that price controls like the ones Warren is proposing could actually exacerbate inflation:

[I]f price controls do cause empty shelves — as they will if they’re strong enough to overcome the amount of monopoly power in the economy — that this will cause people to engage in hoarding behavior. Martin Weitzman explained how this can happen in a 1991 paper called “Price Distortion and Shortage Deformation, or What Happened to the Soap?”…

And when we’re talking about inflation as a price control measure, hoarding could be especially bad. It would boost demand (because everyone is trying to hoard), which will lead to even more inflation, causing the government to respond with even more price controls, etc. That would be a very unpleasant spiral, even beyond the hardships and unfairness created by hoarding. This possibility of a price-control-inflation spiral has occurred to economists, but it’s very hard to measure. Anecdotally people talk about cases where something like this seems to have happened.

And that’s not the only theoretical reason why price controls could exacerbate inflation. Many economists theorize that inflation is, at least sometimes, determined by people’s beliefs about monetary policy. If people think the government (especially the central bank) doesn’t care that much about fighting inflation, then they’ll raise prices now in anticipation of future cost increases, causing fear of inflation to become a self-fulfilling prophecy. This is one leading explanation for the high inflation of the 1970s — the oil shocks caused some prices to rise and the Fed didn’t respond, which convinced people that the Fed didn’t care that much about inflation, which caused inflation to spiral upward much more than the oil shocks should have caused just by themselves. It’s also part of the story many economists tell about how hyperinflation — which is truly devastating to a country’s economy — gets started.

In fact, it looks like something along these lines happened in Venezuela, contributing to that economy’s utter collapse.

And even in the cases when price controls didn’t wreck the economy outright — like Argentina’s, or Nixon’s in the 70s — they didn’t suppress inflation much either.

So both theory and evidence suggest that price controls either don’t do much, or make the problem worse. That’s a good reason not to use them.

On top of that, the price control regime in Warren’s bill appears to be poorly designed. Chris Conlon, an economist at NYU Stern, has a thread in which he explains why the implementation is sloppy:

He also notes that Kroger, one of the companies Warren has repeatedly singled out for supposed gouging, has actually suffered higher costs and shrinking profit margins during the recent inflation.

In other words, this bill — and the broader effort to use price controls to fight inflation — looks like a case of ill-advised populism. The economic case for price controls rests on a lot of assumptions about how the economy works, and on even more assumptions about how price controls would work, and even then the case is very weak. History suggests only a small potential upside and a huge potential downside. And these price controls look particularly badly designed, even when compared with past attempts like Nixon’s.

So overall, I think this is not a good bill. Whether it’s good political rhetoric, I can’t say. But I hope nothing like this ever actually passes.

Update: Here is a paper claiming that greater market concentration has led to greater pass-through of supply shocks (not the main cause of the 2021 inflation, but perhaps increasingly important now):

And here is some fairly clear and simple evidence that “greedflation” has not been a big deal so far:

Is anyone left in Washington who wants to fight inflation by reducing deficits and deregulating the economy?

Two ways to allocate a limited resource, by price or by rationing. (And rationing usually ends up with black or gray market and become price anyway). Whether corporations were greedy (which they are) or altruistic, if you don’t have enough good to provide everyone, you have to keep increasing prices until you do.