Give us all the refugees, dammit!

America used to open our arms to people fleeing war and tyranny. We need to get back to that.

My great-aunt Edith (actually my grandmother’s first cousin, but that’s clunkier to say, so we always called her my “great-aunt”) was born in a region that’s now part of western Ukraine. Sometime in the middle of World War 2, she found herself on a cattle train, being taken from Auschwitz to another concentration camp. Everyone on the train knew they were going there to be executed. My great-aunt somehow saw an opportunity when the guards were distracted, and leapt from the moving train. She was shot in the leg, but escaped into the woods and managed to clean the wound all by herself. Over the course of the next year, after a series of harrowing escapes, she made it to a refugee camp that the Allies had set up in Italy. She lived in that refugee camp for about four years, before finally being allowed to move to the U.S. and settle there, thanks to the Displaced Persons Act of 1948. She went into the finance industry, was quite successful, and lived into her late 90s. (I learned all this from watching a video interview with her, which was part of a large Steven Spielberg project to collect stories of Holocaust survivors in the 1990s.)

I am glad she made it here.

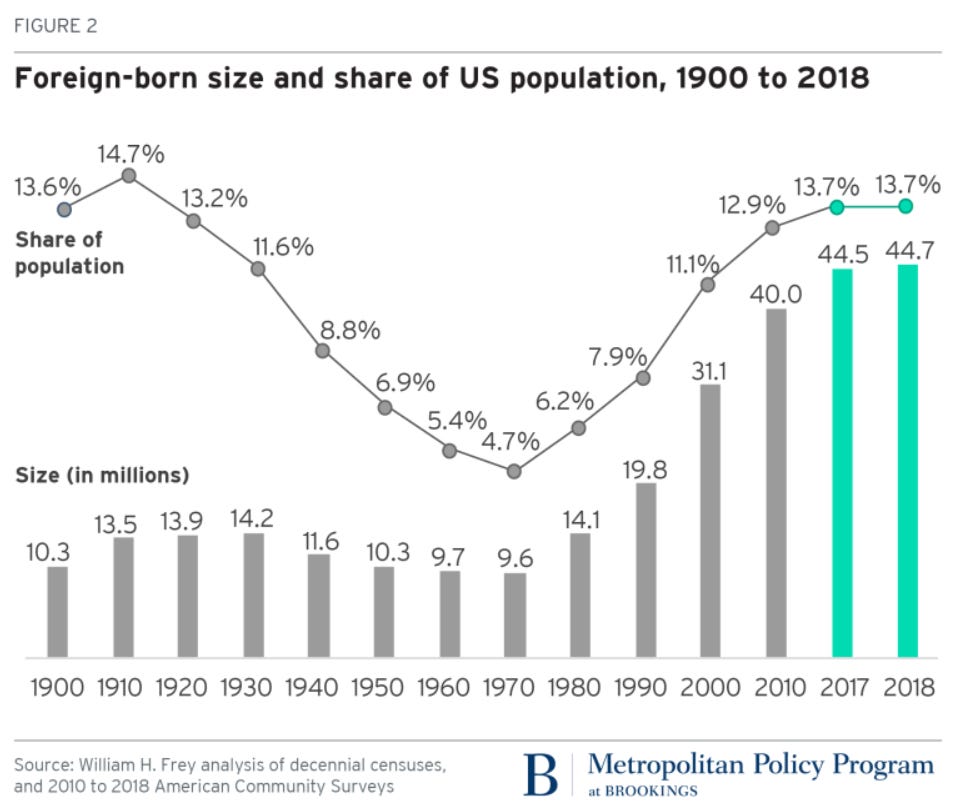

The Displaced Persons Act of 1948 was a compromise. The U.S.’ self-appointed role of champion of universal human rights, and its international reputation as one of the powers that defeated Hitler, forced it to admit refugees from Hitler’s genocides and wars. But this ran strongly counter to the nativist movement that had risen in the 1910s and become ascendant in the 1920s. A series of restrictive laws, culminating in the infamous Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, made it very difficult for immigrants to come to America, and nearly impossible for immigrants who weren’t White. The result was that the foreign-born percentage of the American-born population declined for half a century, hitting its nadir in the early 70s.

As a result, the Displaced Persons Act of 1948 was highly restrictive, and included provisions to discriminate against Jews and Catholics. Truman, angry at this lingering nativism and discrimination, signed it only reluctantly and with protest. Over the next few years, the act was amended to allow more people in, but only about 450,000 World War 2 refugees ended up coming out of a total of over 10 million. The nativism of the early 20th century died hard.

But it did eventually die. The Displaced Persons act was only one of many legal changes that made it easier for immigrants to reach American shores, including the Hart-Celler reform of 1965 and culminating in the Immigration Act of 1990. Those liberalizations restored the foreign-born percentage to pre-1924 levels. And refugee admissions were always a part of that. The Superman comic above is from 1960, and was part of a sustained cultural push to normalize refugee acceptance as a uniquely American activity. Throughout the Cold War, admitting refugees (and asylees, which are technically a different thing) became a way for the U.S. to trumpet its superiority over the communist bloc, since refugees were vastly more likely to flee in one direction.

This tradition continued into the 1980s. It was the cornerstone of Ronald Reagan’s farewell address in 1989:

I've been reflecting on what the past 8 years have meant and mean. And the image that comes to mind…was back in the early eighties…[A]sailor was hard at work on the carrier Midway, which was patrolling the South China Sea…The crew spied on the horizon a leaky little boat. And crammed inside were refugees from Indochina hoping to get to America. The Midway sent a small launch to bring them to the ship and safety. As the refugees made their way through the choppy seas, one spied the sailor on deck, and stood up, and called out to him. He yelled, “Hello, American sailor. Hello, freedom man.”…

Because that's what it was to be an American in the 1980's. We stood, again, for freedom.

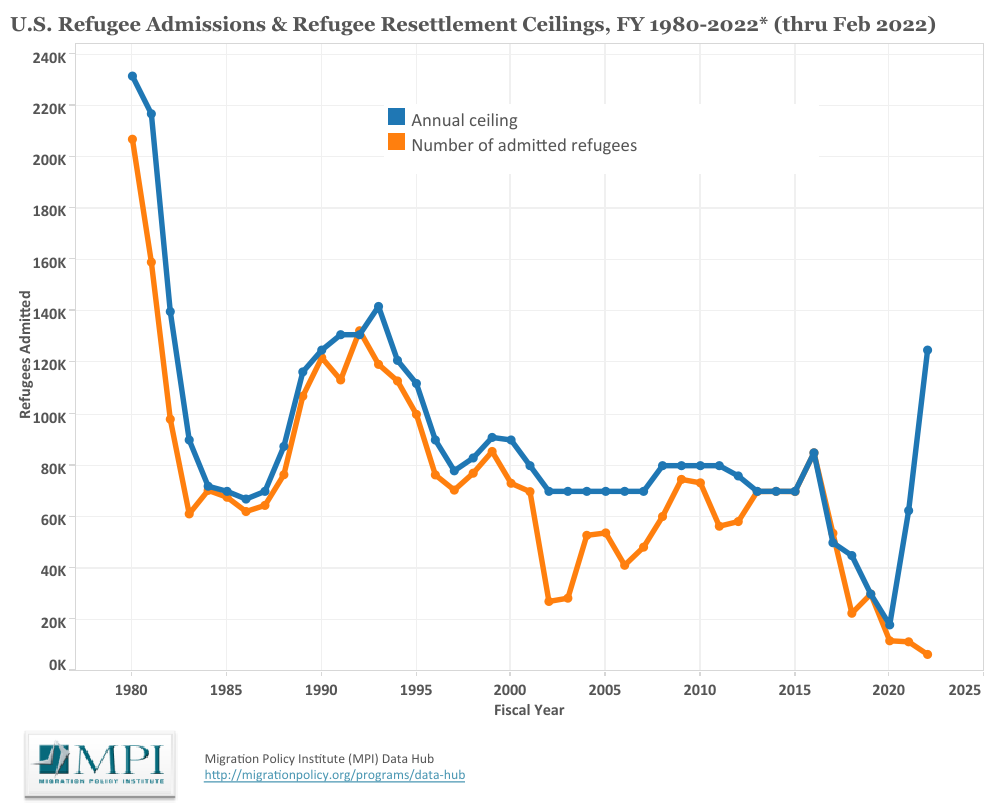

Throughout the 1980s, and for most years until Donald Trump took office, the U.S. resettled more refugees than the entire rest of the world combined:

Resettled refugees don’t represent the total of all refugees; most stay in the countries they flee to, which are usually directly over the border, or return home after the fighting or oppression has ended. But the graph above still speaks to how profoundly America changed from the xenophobic, closed-off place it had become in the years leading up to World War 2.

Now the country is rotating back toward nativism. Trump dramatically reduced the number of refugees the U.S. accepts. But simply electing Democrats may not be enough to flip the switch back to where it was. Early in his presidency, Biden attempted to keep Trump’s new, lower refugee cap in place, before a wave of liberal outrage forced him to raise the cap from 15,000 to 62,500 per year. In 2022, he raised the cap to 125,000, which is a high level historically. But the actual number of admitted refugees hasn’t yet come anywhere close to the higher cap:

Biden’s administration has proven especially resistant to taking in Afghan refugees. The administration’s pullout from the country and the subsequent Taliban reconquest stranded a great many Afghans who worked for the U.S. as interpreters and in other capacity, as well as a far greater number who stand to be oppressed by the Taliban’s tyrannical regime. But only a relatively modest number — about 76,000 — have been taken in so far, and many of these are under a temporary program that may ultimately force them to leave. Part of this is because the networks of NGOs and government workers that helps resettle refugees deteriorated during the Trump years.

But part of it is probably that nativist sentiment is still ferocious among a subset of the American population. And that nativism is especially strong against Muslim refugees from the wars in Afghanistan and Syria. In 2017, author Cheryl Benard — whose husband, ironically, is an Afghan immigrant — wrote an article alleging that Afghan refugees are far more prone to sexual assault and other crimes than refugees from other places, and blaming a “mind-boggling” European crime wave on Afghans.

This was all hearsay; there was never any solid evidence to back up the allegation. When Alex Nowrasteh and Michelangelo Landgrave of the Cato Institute looked at the data on Afghan criminality, they found that Afghans were only 8.5% as likely to be arrested as the average American. But hard data never seems to do much to dispel stereotypes and fears.

Now, the world is being confronted with an even bigger refugee crisis — the one from the war in Ukraine. Already, after just one month of high-intensity destruction by the Russian invaders, over 3.7 million Ukrainians have fled their country. The bulk of these have gone to neighboring Poland, or to other East European countries nearby:

The U.S. has pledged to take in 100,000 of those refugees — a number that will not count toward the annual cap. But this is a modest number — only 2.7% of the refugees the war has created thus far — and it’s not yet clear whether the same murky administrative difficulties that have so far prevented the regular annual cap from being filled will spill over to this effort as well.

It seems possible that we’re experiencing a milder version of the 1948 syndrome — a leadership that understands that America needs to step up and accept more refugees in order to solidify its global role as the champion of freedom, but which is hobbled by the legacy of a recent nativist backlash.

Fortunately, the U.S. public seems to be warming up to the idea of taking in lots of the Ukrainians fleeing Putin’s bombs. Anecdotes suggest that the Ukrainians who have made it here are receiving warm welcomes. And public opinion polls indicate that although Democrats are much more pro-refugee, a majority of Republicans also supports taking in “thousands” of Ukrainians:

The piteous plight of the Ukrainian refugees is readily visible to the millions of Americans who are closely following news of the war:

As is the utter devastation wrought by Putin’s death machines:

So it’s a good sign that Americans are reacting to this and starting to come out of the nativist shell that many retreated into during the Trump years. Hopefully the warmth and sympathy people are feeling toward Ukrainian refugees can be extended to Afghan refugees as well. Racial and religious discrimination, and the scare stories spread by people like Benard, are obviously a big barrier here. But if the Ukraine war helps push America back toward the kind of refugee policies we embraced in the mid and late 20th century, so much the better.

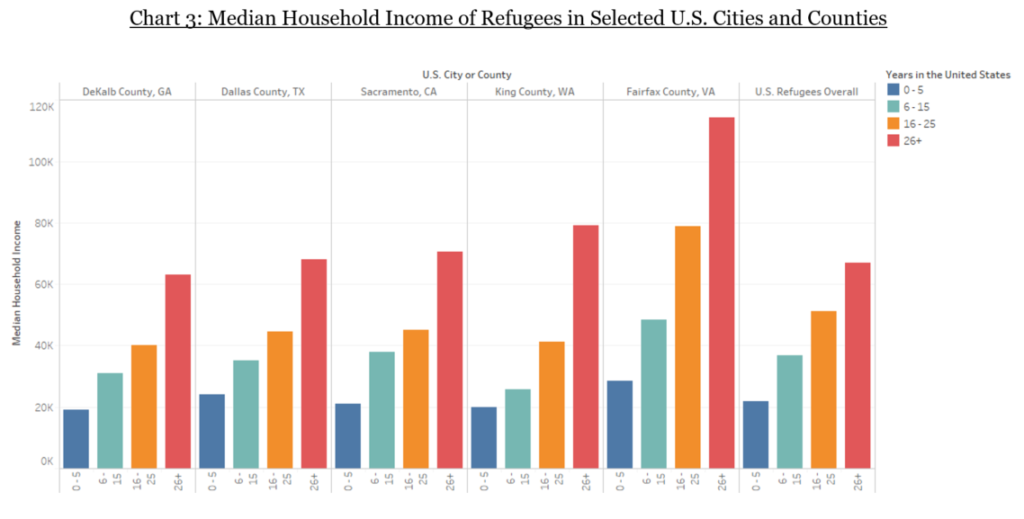

Of course, I should talk a bit about the economics of refugees here. Lots of people stereotype refugees as poor people with low levels of education. That stereotype tends to be accurate at the point in time when refugees arrive. But, like my great-aunt, refugees tend to start out poor and work their way up the economic ladder. A 2017 paper by Evans & Fitzgerald tells the tale:

Refugees have much lower levels of education and poorer language skills than natives and outcomes are initially poor with low employment, high welfare use and low earnings. Outcomes improve considerably as refugees age. After 6 years in the country, these refugees work at higher rates than natives but they never attain the earning levels of U.S.-born respondents…[W]e estimate that refugees pay $21,000 more in taxes than they receive in benefits over their first 20 years in the U.S.

No, refugees don’t tend to be the kind of high-skilled immigrants who come on an employer-sponsored green card or an H-1b. They take a few years to find their feet. But they work hard, and they move up, and they pay more in taxes than they take in government benefits. Ultimately, they give a boost to the whole economy.

A report from the nonprofit New American Economy finds the same, and they have a nice chart showing how refugees move up over time:

And this improvement also continues throughout the generations, with refugees’ children moving up in the economy much as the children of other immigrants do.

What about the labor market? Do refugees take jobs away from native-born Americans? Many people tend to think of immigration as purely a labor supply shock, increasing the number of workers. But as I explained in a post back in 2020, immigration is also a labor demand shock, increasing the number of consumers. And empirically, these two shocks tend to just about cancel out in terms of their impact on wages.

In fact, refugees are one of the easiest immigrant populations to study empirically, because refugee waves are so unexpected. Refugees come to flee war and tyranny, not to make a bet on the local economy. So lots of papers studying the economic impact of immigration actually look at refugees specifically. And what do they find? Here, I’ll repost my list from 2020:

“Is It Merely A Labor Supply Shock? Impacts of Syrian Migrants on Local Economies in Turkey”, by Doruk Cengiz and Hasan Tekguc

This paper analyzes the effect of refugees from the Syrian War who went to neighboring Turkey. They find no negative effect on Turkish workers, even at the lower education levels. They find, increases in local demand and investment, consistent with the idea that immigration is a positive labor demand shock.

“The labor market impact of refugee immigration in Sweden 1999–2007” by Joakim Ruist

Wages are set by sectoral bargaining in Sweden, so instead the author looks at the effects of refugee waves on employment. He finds immigrants don’t cause unemployment for the native-born.

“The Impact of Syrian Refugees on the Labor Market in Neighboring Countries: Empirical Evidence from Jordan”, by Ali Fakih and May Ibrahim

Another Syrian-refugees-to-Turkey study. They do find some slight negative impacts of the immigration — slightly higher housing and food prices, and a slight reduction in internal migration to the areas with lots of refugees. But no labor market impact.

“The Impact of Mass Migration on the Israeli Labor Market”, by Rachel M. Friedberg

This study is about Jews who left the former USSR and moved to Israel when the USSR fell. It looks at occupational categories that had lots of refugees vs. those with fewer refugees and finds no negative impact of immigration.

“Immigrants’ Effect on Native Workers: New Analysis on Longitudinal Data” by Mette Foged and Giovanni Peri

This study finds that when refugees fled to Denmark in the 80s and 90s, less-educated Danish workers got more education and ultimately had higher wages — in other words, immigration increased native-born wages in the long run.

“The Labor Market Effects of a Refugee Wave: Synthetic Control Method Meets the Mariel Boatlift”, by Giovanni Peri and Vasil Yasenov

This paper studies the Mariel Boatlift, in which Fidel Castro kicked a bunch of mostly low-skilled people out of Cuba to Miami. They carefully compare Miami’s labor market to that of other cities, and find no negative effect, even for high school dropouts.

As you can see, not much of a negative labor effect, if any at all.

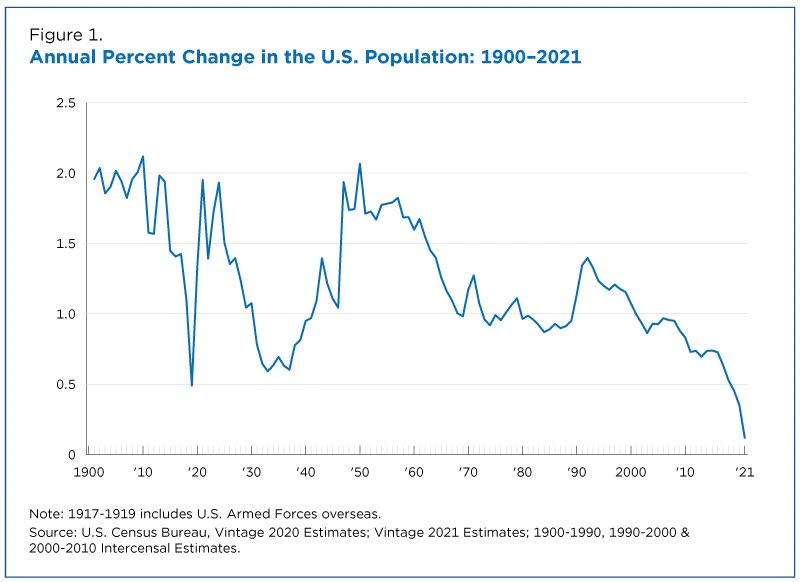

I could stop here. Helping refugees is a humanitarian act that has positive fiscal benefits and little or no negative impact on the labor market. But on top of all that, I should point out that America needs population growth right now. In 2021, the U.S. population grew only 0.1% — the smallest increase ever recorded in the entire history of the country.

Part of this was due to Covid-related death, but much was due to a combination of lower birth rates and a collapse in immigration.

As Japan and many other countries have discovered, a rapidly aging, declining population saps much of the dynamism from an economy, reducing productivity and increasing the number of retirees that each working person has to support. And population shrinkage creates half-abandoned, hollowed-out towns full of despair. To reduce that burden and minimize that despair, we need to keep population growth going at a steady, moderate pace if we can. Refugees, with their proven track record of hard work, are a great way to help do that.

We don’t just owe it to the world to take in refugees — we owe it to ourselves.

My great-aunt came to America at a time when we were just starting to remember our role as a haven for the persecuted and brutalized people of the world. Hopefully we’re living through another moment right now. Refugees make our country better, and we make ourselves a better country when we take them in. It’s been that way from day 1.

I really would like to see more work on the Afghan refugees issues re. crime. For example that BBC report, based on German statistics, seems to disagree with your conclusions.

Punchline : "When it comes to violent crime, 10.4% of murder suspects and 11.9% of sexual offence suspects were asylum-seekers and refugees in 2017. This is despite their population representing just 2% of Germany as a whole".

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-45419466

It's certainly true that Europeans aren't keen on more Muslims coming in Europe. I'd like to point out that Muslims are maybe 8-10% of the French population and, regardless of whether the bulk of the integration problem is due to racist natives or to communitarian immigrants, the result is that we have a badly integrated Muslim minority and the issues that this situation creates don't seem to resolve over time.

I used to say it was very comparable to the problems generated by the Hispanic/Latin/Mexican immigration in the US at the height of the pushback of 90s/early 00s but that seems to have calmed down quite a bit - with Hispanics eventually integrating just like other immigrant waves before them.

We don't seem to be able to achieve that integration in Europe...

I very much agreed with Noah’s post last year “Love It and Leave It”. I would add that travelling in other countries also gives us some perspective on our homeland that we would not otherwise have. Yesterday’s post made me think about what I have learned about my country and myself from immigrants I have known. When I was in grad school, one of my fellow students who was from a repressive nation said to me, “You Americans are so lucky to have your Bill of Rights.” I have to say that I had never given the Bill of Rights much thought; it was something I had to learn about in a high school government class. But, as my friend pointed out, I’ve never lived in a fascist country.

I have worked in the high tech field. One of my colleagues, from a European country, told me that she had inquired about a job in her home country and was told the job was for men only. When she told them that would be illegal in the United States, she was told she could return to the US. Another female colleague, a university professor, told me that in her country, the male members of her family practice professions such as medicine and engineering, while the women do not attend school past about the sixth grade. She told me how lucky I am to have been born here.

That said, I have to mention that in my experience issues such as sexual harassment have been more common when I have dealt with men from countries where women have a lower status than in the US. American men are either more enlightened or better socialized.