Ghana, you were doing so well!

Africa needs a development leader. Ghana can't afford to play the game of borrow-and-bailout.

(Note: In the initial version of this post, I read an exchange rate chart upside down, which caused one paragraph to be wrong. I have now fixed the chart and updated the relevant text. The basic conclusions remain the same!)

So, unfortunately, it’s time for another one of these. By which I mean both a “[Country], you were doing so well!” post, and a “Why [country] is having an economic crisis” post. I thought Ghana was going to be one of my development success stories, and then before I got around to writing about, its economy went into a crisis. The basic story here is that Ghana just defaulted on most of its external debt, and is experiencing very high inflation, and is going to have to be bailed out by the IMF. That’s going to result in financial and economic chaos in the country, a year or two of depressed economic activity, and hardship for the Ghanaian people.

I’m sure Ghana will eventually bounce back. And as I’ll explain, when we look at the particulars of how this crisis has played out, we see that the government is being smarter than many. But overall this is pretty disappointing. So first I’ll talk a bit about why it’s so disappointing, and then move on to the crisis itself.

Why Ghanaian development is important

Obviously Ghana’s development is most important to the ~32 million people who actually live in Ghana. But it’s also important in the broader context of African development, because it’s one of the leading candidates to become the “first mover” in the region.

Africa is really, really poor. Not just compared to rich countries like the U.S., but compared to other developing regions. In 1990, fewer than 1 out of every 7 people living on less than $2.15 a day (the poorest of the poor) lived in Sub-Saharan Africa; by 2019, it was 3 out of 5.

Here’s the income of Sub-Saharan Africa compared to South Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East and North Africa — the other regions we typically call “developing”. (Note: The World Bank defines these regions, so if you think it’s weird that the African continent is split up like this, go take it up with them!)

South Asia has started to climb out of poverty, while Latin America and the Middle East are stagnant at a middle income level. Sub-Saharan Africa is the only major region that’s both stagnant and very poor. That’s a human disaster, not just for the people living in the region today, but for the increasingly large percent of humanity that will live there in the century to come.

Currently, with the exception of a couple of tiny island countries in the Indian Ocean far from the rest of the continent, there is no African country that you could really call “industrialized” — not even South Africa. Resource extraction dominates the region’s export economies, and local services dominate its domestic economies. Some economists like Joe Stiglitz and some others are pessimistic about African industrialization, and claim the continent needs to find a new path to wealth; I personally tend to agree with the people who think industrialization is still the best route out of poverty.

But regardless of which growth model is the best, I believe that Africa needs a country or countries that pioneer that model. This is a pattern we’ve seen in Europe, East Asia, and Southeast Asia. In Europe, it was British industrialization that provided the model for continental Europe (though they made their own tweaks). In East Asia, Japan led the way. And in Southeast Asia, Singapore and Malaysia were the first movers. These “regional seed” countries didn’t just provide institutional and business models for their neighbors to follow — they provided financing, created supply chains, and gave birth to regional agglomeration and clustering effects. And I’m guessing that they also exerted an inspirational effect — poor neighbors probably saw the first movers get rich and thought “If they can do it, we can do it too.”

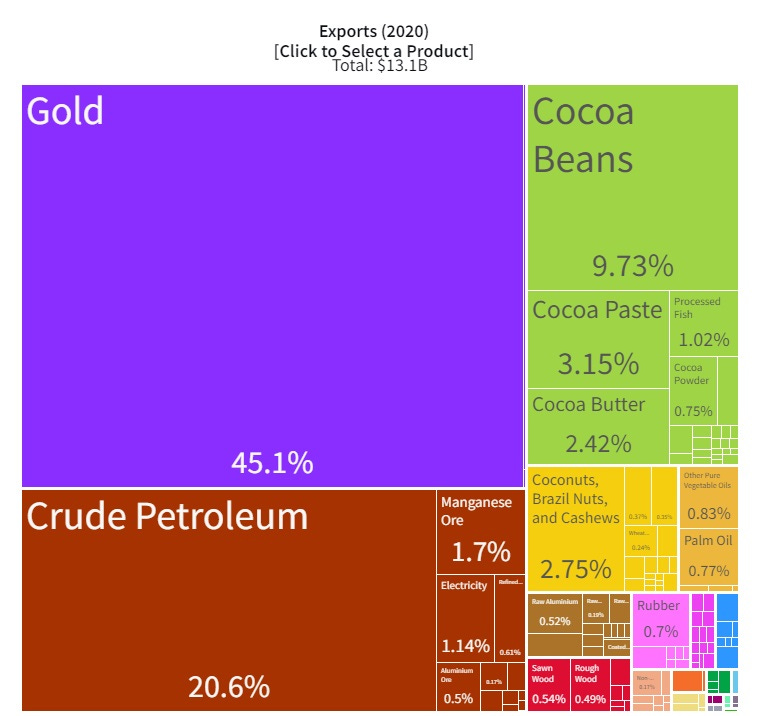

Sub-Saharan Africa, which is far from those other clusters, has no such “seed” country right now. Two main candidates, which a lot of people were keeping a close eye on, were Ethiopia and Ghana. Ethiopia, which Tyler Cowen and I were both bullish on, looked like it was starting to develop a robust manufacturing sector, based in large part on Chinese private investment in labor-intensive industries. Sadly, that country’s civil war largely put a stop to its promising growth, at least for now. Ghana, in contrast, is a resource exporter:

Resource exporters aren’t the kind of country you generally expect to lead the way to industrialization. Indeed, Botswana is much richer than Ghana, and its main export industry is diamond mining, and no one expects it to lead the way to industrialization. But the fact that Ghana’s resource exports haven’t yet let it escape poverty actually seems bullish, because it means labor costs could be low enough to attract investment for low-end manufacturing — i.e., the way industrialization usually gets started. So Ghana might be able to switch over to manufacturing. And West Africa is a fast-growing market, and you can’t import everything, so there’s an opportunity to make stuff locally.

Ghana seemed best positioned to take that opportunity, due to its big leads in health, education, governance, and stability. Here’s what I wrote for Bloomberg in 2020:

Ghana has a number of big advantages over other countries in the region in terms of geography, institutions and human capital. It’s on the coast and has plenty of ports that can be used to ship and receive goods. With about 31 million people, it has a large enough population to create a substantial domestic market but small enough that providing jobs and food won’t be too insurmountable of a challenge. Members of the Akan ethnic group make up about half of the population, meaning that Ghana has less of the ethnic fragmentation plaguing many post-colonial states. It scores well on international indicators of governance quality, freedom, democracy, ease of doing business and corruption. Ghana has lower child mortality than its neighbors, indicating a relatively healthy populace. It also has a head start in terms of literacy rates and education.

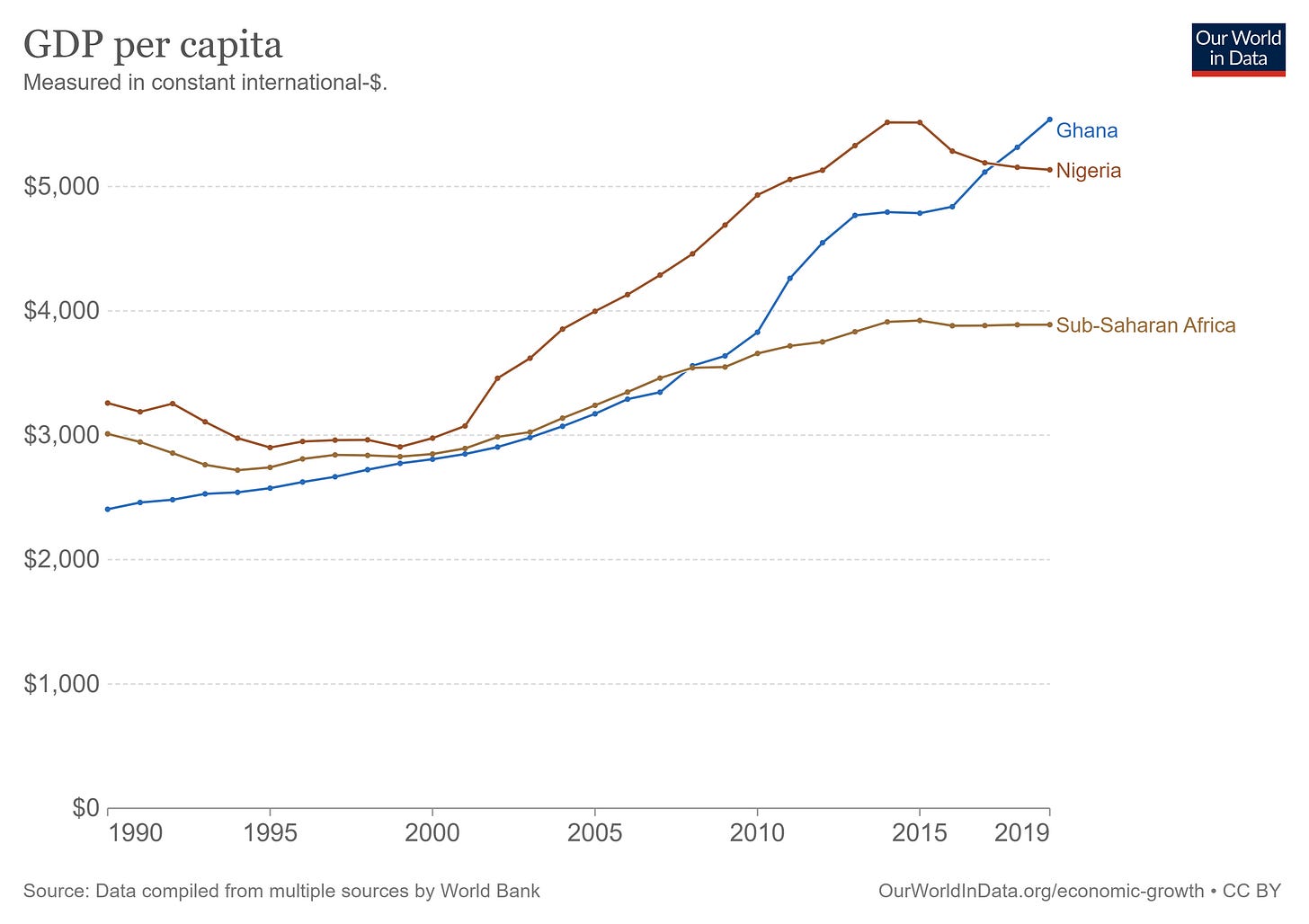

In the 2010s, Ghana experienced steady and fairly rapid growth, even as Sub-Saharan Africa as a whole stagnated. It was still subject to the vagaries of global natural resource prices, but it performed clearly better than nearby Nigeria:

Ghana’s government certainly hoped to shift the country toward manufacturing, rolling out a pretty standard industrial policy based on attracting FDI through pro-business reforms, investment in transportation and electrical infrastructure, and the creation of special economic zones. The explicit goal was to be a manufacturing export hub serving the surrounding region.

And there were some early glimmers of hope that this smart strategy was working. Even as natural resource income and overall GDP surged, manufacturing grew strongly enough to hold steady as a percent of the economy (at around 10-11%). Foreign car companies like Nissan and Volkswagen started to build some factories in Ghana. Chinese investment interest ticked up as well. The SEZs were heralded as export successes, especially the Tema Free Zone. Like Indonesia, Ghana was shaping up to be an interesting experiment on whether a country can make the jump from being a resource exporter to being an industrial up-and-comer.

Then macroeconomics got in the way.

Speedrunning an emerging-market crisis

You’ll recall from my post on Sri Lanka’s economic crisis back in July that emerging-market crises tend to look very similar:

The crisis itself tends to come from a rapid depreciation of the exchange rate. This makes it harder to afford imports like food and fuel — Ghana’s top import is refined petroleum and its third biggest import is rice, so that tells you that Ghana’s people are pretty vulnerable to a depreciation. And looking at the chart, we see that the Ghanaian currency, the cedi or GHS, lost a huge amount of value over the past year:

(Note: This is the chart that I originally read upside-down! Be careful with that, folks! This pattern makes a lot more sense.)

Meanwhile, Ghana’s situation is being exacerbated by two other common features of emerging-market crises — debt default and high inflation. The prime culprit for these things is usually foreign-currency-denominated debt. Remember that if you borrowed a million U.S. dollars when the cedi was strong and now suddenly a cedi is worth far fewer U.S. dollars, well…you still owe a million U.S. dollars! At that point you can either default on the debt, or print a bunch of money to pay it off (causing high inflation), or both.

And Ghana has certainly been borrowing a lot of external debt over the past 15 years or so:

All this is going to be in foreign currencies. Ghana is not the type of country that can borrow overseas in its own currency.

This was only part of Ghana’s government borrowing, all of which together raised government debt to about 100% of GDP — a number that’s sometimes OK for a rich country, but very unwise for a developing country where things can go wrong so easily. It spent this money on trying to build out an oil industry that ended up producing underwhelming returns, and on some other ill-advised projects as well.

Ghana’s inflation, however, doesn’t appear to be due to an attempt to pay off external debt by printing local currency. In fact, the central bank has been raising interest rates very fast in order to fight the inflation from food and fuel prices, as well as in a (failed) attempt to halt currency depreciation. So this is not the typical “print money to pay off foreign debt” story we’re seeing.

Higher interest rates, unfortunately, exacerbate the government’s debt burden. Ghana is not a country that can borrow cheaply in the first place, and global interest rates have been going up, so the central bank’s rate hikes have just added fuel to the fire. Interest on the government debt is now absorbing 70% of tax revenues, which is crowding out anything else useful the government might try to do, and which is obviously unsustainable.

The huge debt burden, in turn, probably led to soaring inflation. Ghanaian businesspeople looked at the mountain of government debt and decided that eventually the government would reverse its pattern of rate hikes and resort to printing a ton of money to pay off its debt. So they got in ahead of the game and started raising prices, which made inflation a self-fulfilling prophecy. Economists call this kind of thing the “fiscal theory of the price level”.

Ghana’s government, however, didn’t decide to inflate the debt away; instead it just defaulted. This was a wise move. 58% of Ghana’s government debt is owed to foreigners, so defaulting on this drastically lowers the country’s overall government debt burden even as it also makes the government less vulnerable to further downward currency movements. The default will hurt, for sure, but it will also restore confidence and make it much easier to get a bailout from the IMF — which Ghana is currently doing.

In other words, Ghana basically did a speedrun of its emerging market crisis, getting the pain over with and skipping to the recovery phase. (Note: When I had read the exchange rate chart upside down, I thought it was a VERY quick default. But even reading it the right way, it’s clear that Ghana defaulted before A) the exchange rate crashed severely, or B) the central bank was forced to hyperinflate.)

That was smart. And it gives me some hope that Ghana’s government is being more competent about this whole thing than its counterparts in countries like Sri Lanka. I expect Ghana to start on the road to recovery very quickly, and I’m happy to see that the government is capable of decisive, wise, politically difficult actions.

That being said, I am still pretty disappointed with the way the crisis happened in the first place. Having the government borrow all that money in the first place was not smart. It appears that Ghana’s leaders have become addicted to the cycle of debt and bailout — this is the 17th time the IMF has helped them out of debt, which is a little ridiculous. At this point the IMF needs to start looking at how to gently but firmly cut Ghana off, so that they don’t keep doing this.

I’m also disappointed that so much of the borrowed money was spent trying to start an oil industry. I know Ghana is a poor country that needs to escape poverty any way it possibly can, but at the same time, its fundamental challenge is escaping the Resource Curse. Investments should be focused on manufacturing — on infrastructure, education, and capacity building, and perhaps on export incentives. If Ghana’s oil industry had worked out, its economy just would have become a bit more like Nigeria’s — and that is not a desirable goal.

I remain optimistic that Ghana will eventually become the “seed country” for West African industrialization, and possibly even for African industrialization as a whole. But it needs to stop playing this game of borrow-and-bailout, and learn to stand on its own two feet. I believe it has the basic resources it needs to do this.

Indeed, this is sad to see. Another worry in this area is increased terrorist threats which appear to be getting deeper into Burkina Faso, Ghana's northern neighbor: http://news.aouaga.com/h/146172.html

That this might happen so far south when I lived there 9 years ago was unfathomable. But here we are.

How can this analysis ignore lockdowns and a panicked pandemic response globally as a proximate cause for the crisis?

Ghana spent billions on lockdowns, closed schools (for a year!) and scared people into not seeking immunisations for diseases far more serious than Covid. From an early point it was clear that the population was never at risk of covid being a serious health burden due to age structure.

More broadly, this is the result of rich nations spending trillions to shut down the global economy and printing money to keep people compliant. The resulting debt bubbles, inflation and interest rate rises were always going to affect developing economies with weak currencies the most. These costs were barely, if ever, mentioned in domestic media or academic discussions of pandemic policy. It’s much harder to conceptualise the health damage of 100 young people kept in poverty over a decade than it is to imagine the death of a single elderly person due to a disease that dominated every news discussion for two years. That’s why “shut it down” won so comprehensively globally, despite the lack of any cost/benefit proportionality.

Developing countries who were teetering on the edge of progress decided to collectively shoot themselves in the foot and take hundreds of millions of children out of schools and into poverty. The global financial crisis created by lockdowns is now pushing them over the edge. History will look back on the episode very poorly.