Germany needs to stop messing around!

The industrial heart of Europe can no longer afford to indulge complacency and bad policy.

Germany is the heart of Europe. It’s the region’s largest economy by a significant margin, and it’s the most populous nation in the EU. It’s also by far the region’s biggest manufacturer:

As Germany goes, so goes Europe itself. And yet everyone seems to agree that good old Deutschland is now in big economic trouble. Here’s the AP:

For most of this century, Germany racked up one economic success after another, dominating global markets for high-end products like luxury cars and industrial machinery, selling so much to the rest of the world that half the economy ran on exports…Now, Germany is the world’s worst-performing major developed economy, with both the International Monetary Fund and European Union expecting it to shrink this year.

And here’s an article from Bloomberg detailing the grim prospects ahead for the German economy. There are many scary graphs, but here’s the one that stood out the most to me:

The WSJ declared that “Germany is losing its mojo”. Joey Politano has a long blog post with many charts showing the woes of Germany’s manufacturing sector. The Economist has numerous recent articles with titles like “Is Germany once again the sick man of Europe?”, “Germany is becoming expert at defeating itself”, and “The German economy: from European leader to laggard”. And so on.

These articles tend to focus on the problem of Russian gas cutoffs, which have raised energy costs for German manufacturers. But if you look at a chart of Germany’s GDP growth, you can see that a noticeable slowdown began around 2018. The country’s economy, which grew so robustly in the decade following the Great Recession, has almost flatlined since then:

After reading endless articles about Germany’s malaise, my considered opinion is that it boils down to three big mistakes: trusting its economic health to Russia and China, a naive degrowth-focused environmentalism, and a reluctance to embrace change and progress. On all three counts, the country seems not to recognize the magnitude of the challenge. Instead they seem to be just muddling along, dreamily expecting the economy of the mid-2010s to somehow magically return.

Germany needs to stop messing around and get serious about fixing its economic model. The fate of Europe rests on its shoulders.

Germany has trust issues (it has too much of it)

The economist Robert Solow once remarked that discussions of European growth tend to degenerate into “a blaze of amateur sociology”. Well, here’s my amateur sociological anecdote. A little over a decade ago, a man from the German government came to give a talk to the University of Michigan economics department about a new data set the German government was collecting from businesses. A professor asked whether we could trust the data, given that reporting fake numbers might help German companies avoid taxes. The government employee’s eyes went wide with shock, and he said, in his charming German accent: “Oh no, they cannot do that. That would be against the rules.”

Oh, well in that case.

Germans trust their government more than people in almost any other rich country on the planet. Trust in government is often a good thing for the efficient functioning of a society (although I can also think of a couple of times when it has gotten the country into trouble). The problem is that in the last quarter century, Germans have extended that trust to countries and institutions that don’t deserve it.

One glaring example of someone Germans shouldn’t have trusted is my country and our stupid and greedy banks. In the leadup to the crash of 2008, German banks very often behaved as the “dumb money”, buying whatever toxic mortgage-backed bonds their American counterparts sold them, and trusting the ratings agencies that lent their imprimatur to those bonds. This naivete ultimately meant increased pain for the German financial system and economy when the whole house of cards inevitably collapsed.

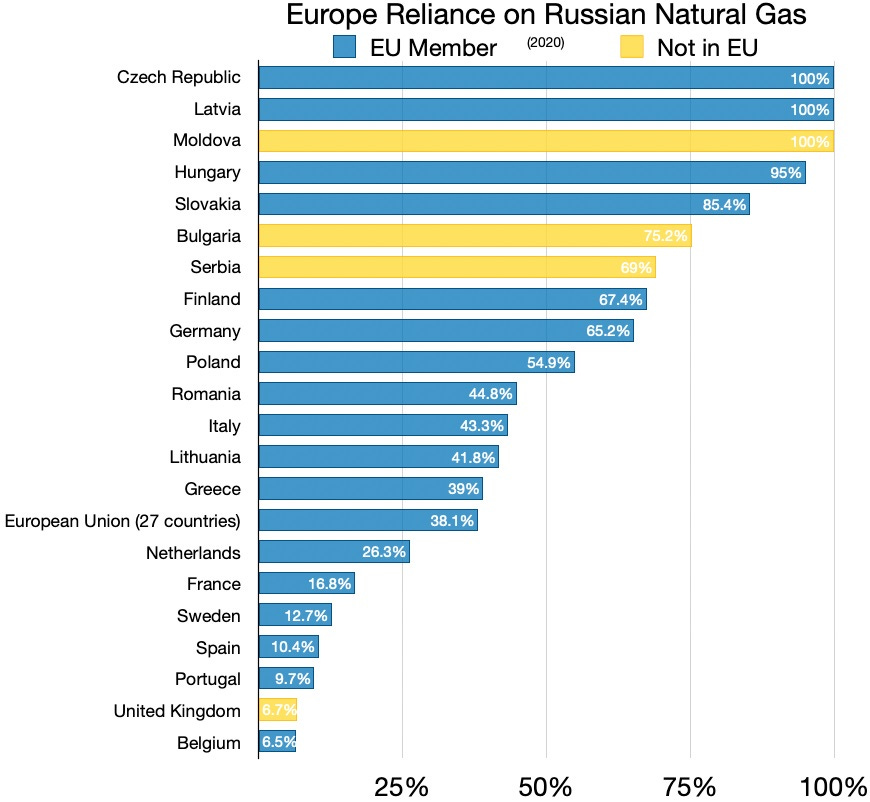

But a far more egregious example of excess trust was Germany’s willingness to allow its industry to become dependent on Russian natural gas, to a far greater degree than most of Europe:

This was partly a conscious decision, driven by the naive belief that increasing Europe’s economic ties with Russia would create durable peace in the region. Of course, things don’t work that way, as Germany learned in WW1 when it went to war with its top trading partners, and as it has now learned once again with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But Germany’s willingness to put its economy in the hands of Vladimir Putin was also born of complacency; it was simply the path of least resistance.

Now the country’s manufacturing sector is paying the price, with energy-intensive sectors being hit particularly hard:

Next time you are tempted to think “Perhaps if I put my livelihood in the hands of a revanchist dictator, he will choose to be nice to both me and everyone around me”, please consider the possibility that this is in fact a very bad move.

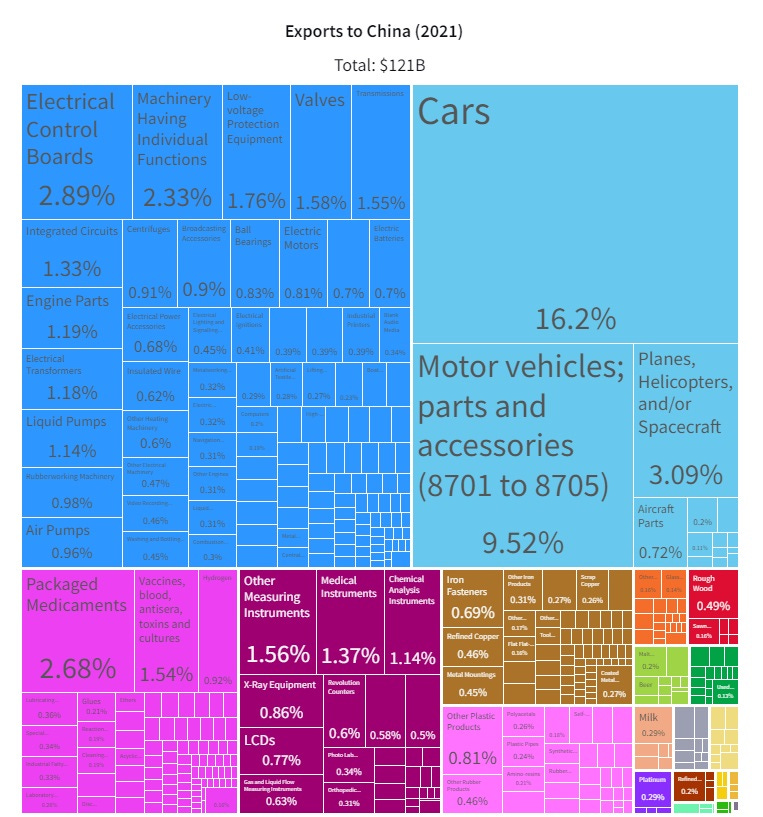

Finally, Germany and its companies trusted China far too much. As most of the above news stories will tell you, Germany’s economy boomed in the 2010s in large part because it was so export-oriented. Most of those exports went to other European countries, but a significant chunk went to China:

It’s important to differentiate between gross exports and net exports here, by the way. Germany ran a trade deficit with China during the 2010s, but its ability to sell lots of stuff to China boosted its economy nonetheless. Most of those exports were vehicles and machinery:

The problem was that China’s government had absolutely no intention of remaining dependent on German vehicles or German machinery over the long term. China immediately began systematically copying and/or stealing the technology of the German companies that did business there, and transferring it to local champions. Here are some excerpts from a story from all the way back in 2011:

"We gave them our description of the product we wanted - all the photographs, everything we used in order to to sell it over here in Germany" he says, recalling how a company he was involved with started making components in China.

"We asked them to manufacture it. They did that, but after half a year very, proudly they came back to us and showed us their own product, which they intended to sell in Germany.

"And it was a copy-cat of what we did, so they copied all our material. They took our photographs. They took our descriptions. Everything."

Mr Fischer was particularly amazed at one aspect.

"The interesting thing is that they had no bad conscience about it," he says.

"They openly told us what they were doing, not even understanding that this was not something that we gave to them so they could use it to compete with us."

So what does he think was going on?

"The culture is different," he says.

Of course, much of the theft was also traditional espionage rather than German companies stupidly handing over their crown jewels. And in many cases German high-tech companies like Kuka Robotics simply sold themselves wholesale to Chinese companies that had absolutely no intention of preserving those German enterprises as going concerns.

Anyway, the result has been incredibly predictable to anyone with even a modicum of sense. Having plundered most of what it came to plunder, China is now closing itself off to German products:

The share of Germany’s total exports to China dropped to 6% in the first half of this year from 8% in 2020, when the Asian economy rebounded from its first pandemic shock. This is not a result of Germany’s efforts to reduce reliance on its most important trading partner, but rather a lack of interest from the Chinese side.

Part of Germany’s pronounced economic stagnation since 2018 is due to the fact that this is when its exports to China slowed down.

German leaders, observing this entirely predictable reversal, may be finally waking up and calling for decreased economic reliance on China. I suppose two decades late is better than never, but not by much. The pain from extracting Germany’s supply chains from China will simply add to the pain from finding alternative sources of energy to Russian gas. But that pain can no longer be avoided; Germany’s business and government leaders must simply discard their trust of authoritarian powers and set themselves to the hard task of economic independence.

The wrong way to go green

The transition away from Russian gas would be much easier, of course, if Germany were not simultaneously in the grips of a degrowth-like “green” movement. In fact, Germany’s current prime minister Olaf Scholz, who includes the Green Party in his governing coalition, campaigned on a promise to shut down the country’s nuclear power plants. At the turn of the century, nuclear plants provided almost a third of the country’s electricity; that has now dropped to zero.

Scholz proceeded with the shutdown even in the face of Russian gas cutoffs, claiming (ridiculously) that keeping the plants open would be too technically difficult. At a time when Germany should have been frantically restarting all of its old nuclear plants — at a time when German industry was floundering due to a sudden cutoff of energy — Scholz insisted on getting rid of a zero-carbon energy source. The degree of pugnacious, stubborn self-destructiveness is just staggering.

And even more remarkably, this was done in the face of popular opposition. Two-thirds of Germans opposed the shutdown of the last nuclear plants. Support for nuclear is now soaring among the German public, but Scholz has stuck to his pre-existing ideological commitments. The fact that nuclear produces no greenhouse emissions makes this act even more maddening and incomprehensible.

The nuclear shutdown shows that Germany is in the grips of the same kind of degrowth mania that has afflicted other North European countries. Degrowth is antithetical to decarbonization, and Germany is demonstrating exactly why. The country is trying to build out solar power and electric cars, but it’s having trouble squaring this with the goal of becoming less economically dependent on China, which is where most solar panels and electric cars are made. Germany could make solar panels and electric cars itself, except this is very expensive now, because it doesn’t have the energy available to do so — because it shut down its nuclear plants.

Decarbonization requires growth. It takes energy today to make the infrastructure to produce green energy tomorrow. By instead falling prey to a misguided populist form of degrowth-oriented environmentalism, German’s leaders didn’t just hurt the country’s industry; they slowed its decarbonization. As The Economist shows, Germany is much more carbon-intensive than other major European economies.

In any case, Germans may be getting disillusioned with the Green agenda, but this isn’t necessarily a hopeful sign; so far, a plunge in support for the Green party has mostly benefitted the far-right AfD party.

Germany must embrace progress and change

On top of deindustrialization and an export slump driven by energy mistakes and Chinese competition, Germany is facing stagnation on other fronts.

While the country has a wealth of small high-tech manufacturers (the “mittelstand”), it produces very few new big companies, and has mostly missed the software revolution. SAP is its only big software company of note, despite the fact that it has access to a huge amount of East European programming talent. For decades, the country has notoriously resisted digitization. The country’s leaders are aware of the problem, but their plans to catch up in software seem lackluster so far.

The EU as a whole would generally rather regulate software than make it — a tendency now on display in Europe’s push to try to control global AI through regulation. Germany is not the EU, of course, but it is the most powerful and important EU state, and if its leaders were more proactive and forward-thinking, they’d throw their weight against the region’s stagnationist impulse.

Meanwhile, Germany’s R&D apparatus could use some work. The country, which invented the modern research university a century and a half ago, now has no world-beating research universities — its top-ranking school in the Times Higher Education ranking is the Technical University of Munich at #30, while U.S. News has the best German school as the University of Munich at #47. A big reason for this is that German schools are all free; in the U.S., undergrad tuition cross-subsidizes research spending.

Stagnation is happening in Germany’s built environment as well. The Economist reports on how German housing construction is falling prey to NIMBYism similar to that which afflicts the U.S.:

The government promised to build 400,000 flats a year when it came to power in 2021. Industry groups reckon that something more like 700,000 a year are needed…Whatever the true figure, everyone agrees that the 295,000 built last year did not cut it...

An application for a building permit requires filing eight paper copies with the authorities. Each of the federal republic’s 16 states has different building rules. Cities, and even some of the country’s nearly 11,000 communes, weigh in with their own strictures. Whenever a fault, no matter how minor, is found with an application, the clock for its processing is reset.

This is certainly not good news for the country’s chances of building solar plants to replace the lost nuclear energy, or building new factories to compete with China.

And The Economist also reports on the parlous state of the much-trusted German government itself:

Sclerotic bureaucracy is a problem when companies must adapt to a fast-changing global economy and the entire capital stock serving fossil fuels needs to be replaced. At the moment, it takes more than 120 days for a German firm to receive an operating licence, compared with fewer than 40 in Italy and Greece. Construction permits take more than 50% longer than the oecd average. Clinical trials are so difficult that biotech firms set up research centres abroad. Almost 70% of Germans think the state is overwhelmed.

Overall, these problems paint a picture of a country living in the past, clinging to the way it did things in the glory days, unwilling to confront the difficult adjustments required by changes in technology and geopolitics.

This would be a big enough problem if it were just the livelihoods of German citizens on the line. But Germany’s blundering and stagnation come at a time when Europe needs it more than ever.

Germany must be the arsenal of European freedom

Europe is currently more united than it has arguably ever been, pulling together to oppose Russia’s invasion of Ukraine with financial and material aid. As the U.S. turns its attention to East Asia, Europe will have to increasingly shoulder the burden of furnishing the arms that allow Ukraine to defend itself in the long term. Fortunately, it is doing this; European commitments to Ukraine are now far ahead of U.S. commitments.

As the chart at the beginning of this post showed, Germany has the power to vastly out-manufacture Russia if it chooses to do so. But it is not yet choosing to do so. One key thing Ukraine needs, on an ongoing basis, is a large and steady supply of artillery shells. There are some reports that Russia is making up to 7 times as many artillery shells as the West, and even though the West’s are much more accurate and deadly, that’s still a huge and puzzling production disadvantage. Ukraine is currently firing shells faster than it can replace them, which wouldn’t be happening if Germany was bending its true industrial might toward this task. Currently, German weapons and ammunition backlogs have soared; the stuff just isn’t getting made.

This is consistent with a general German approach of talking big but doing far less than promised. Despite a much-publicized shift in its defense planning, Germany hasn’t yet increased military spending:

Mr. Scholz has failed to deliver on the other piece of the equation — the buildup of Germany’s own defenses. As the war in Ukraine settles into a bloody stalemate, the urgency he described has evaporated…A $109 billion special fund to rebuild Germany’s anemic armed forces over the next few years remains largely untapped. Mr. Scholz backed off his initial pledge to pump additional tens of billions of dollars into annual defense spending to meet a NATO spending target Berlin has long endorsed — and long ignored. Efforts to streamline the country’s cumbersome weapons procurement system are only now gaining traction…

[German] officials say the Defense Ministry’s request for an additional $11 billion for next year is a nonstarter. This even as a poll showed 62 percent of Germans support more defense spending.

At a time when Europe needs Germany to be its Arsenal of Freedom, the country and its leaders are taking the same dithering, bumbling, stagnationist approach that they have taken toward energy, toward Chinese competition, toward new technology, toward construction, and toward everything else. It is a deeply unserious approach, indicative of a country whistling past the graveyard and dreaming of better times.

What Germany needs now is to become a serious country again. It needs to restart every nuclear plant that can still be restarted, even as it accelerates the building of renewables. It needs to cut off any remaining tech transfers to China. It needs to increase spending on the military and rebuild its defense-industrial base. It needs to focus on giving software companies a safe and profitable haven to grow and develop, and encourage more rapid digitization. It needs to quash NIMBYism and allow more building.

Most of all, Germany needs to realize that the easy days of the 2010s aren’t coming back. There’s a difficult path ahead, and it has to be faced head-on rather than ignored. Europe needs Germany to stop messing around.

I honestly don’t understand how they could decide to shut down their perfectly functioning nuclear plants in the middle of an energy crisis. I had the idea - probably a cliché but still - that Germans were more pragmatic than other people, but this degree of stupidity is beyond belief.

If only some USPresident had warned them about being completely reliant on Russian gas. Nah, they'd just laugh him off ....