A lot of people like to criticize GDP as a measure of living standards. Among many intellectuals, particularly in the UK and some parts of North Europe, talking about the limitations of GDP and trying to think of better measures is something of a cottage industry:

Now, there are important senses in which these critics are right. GDP leaves out some things that are very important to human well-being — for example, leisure time, baseline health, inequality, natural habitats, and the value of unpaid housework and child care. And there are things it includes that some people might not want to include — the amount that government spends on tanks and bombs, for instance, or the fees people pay to lose their money in DeFi scams. There are even a few economists who say we shouldn’t even pay attention to GDP and that we should only care about consumption.

For this reason and others, it’s important not to get too obsessed with one single measure of the economy — GDP or anything else. You have to look at a bunch of measures to get a clear picture of what’s happening (in a 2018 Bloomberg post, I suggested also looking at real median personal income, prime-age employment rate, median real weekly earnings, and the Supplemental Poverty Measure). And in fact, I think policymakers and media figures all over the world already look at lots of different numbers.

But today I just want to focus on GDP, because the critics have sorely overstated their case. In fact, GDP is an incredibly useful and important number, for a variety of reasons.

GDP is actually just a measure of income

First, I think that understanding what GDP actually is helps us understand why it’s important. Critics of the concept sometimes seem to lack a basic understanding of what the number even means.

GDP is a measure of the total amount of economic value produced in a country. We measure economic value by how much people pay for stuff. If you pay $100 for a new toaster, GDP goes up by $100. If the government pays $1M for a tank, GDP goes up by $1M.

Now, it can be hard to understand why we’d care about measuring things this way. Just because people pay $100 for something, does that mean it was really worth $100? And on top of that, it can get a little complicated, because there are some things we buy that aren’t included in GDP — intermediate goods (like parts to make a car), used goods, financial assets like stocks and bonds, etc. Explaining these things would take a whole economics lesson.

But instead, there’s an easier way to think about GDP and what it means. Really, it’s just a measure of people’s incomes.

The key to understanding this is to realize that whenever you spend a dollar, someone else makes a dollar of income. If you spend $100 on a toaster at Wal-Mart, some of that goes to workers’ wages, some goes to suppliers, some goes to the people who own the company, some goes to the government via taxes, and so on. But all of it goes to someone. Every dollar that gets spent is a dollar that gets earned.

So if we add up all the wages, profits, rental income, interest income, and taxes earned by the people in a country, that total should just be the same as GDP! Magic, right?

In fact, we do add these things up, with a number called GDI — “Gross Domestic Income”. Actually we have to make some statistical adjustments to the basic formula of wages + profits + rental income + interest income + taxes, but it’s basically just that. And guess what — GDI and GDP are almost exactly identical!

The small differences between the numbers are due to statistical quirks, but you can see that basically these are the same number.

A country’s total production is kind of a complicated concept, but the total income of all the people in a country is a very easy and intuitive idea to understand. You have an income. I have an income. We all know what income means, and why it’s important.

So why do we even bother to calculate GDP? If GDI is the same thing, why don’t we just use that? The answer is that it’s easier and quicker to collect data on sales than on incomes. GDP is just a convenient number to calculate. But really it’s just a measure of income.

Per capita GDP is a great measure of living standards for developing countries

Now, the section above is how we define total GDP — the total production (or income) of an entire country. But often, when we see GDP compared between different countries, it’s actually per capita GDP — GDP per person.

Why would we care about GDP divided by the number of people? In theory, median income — the income of the typical person or household — would be a better measure of the typical person’s living standards. But medians are hard to calculate, because they require doing surveys — you have to go out there and ask everyone how much they earn. For developing countries, it’s very hard to do these surveys and get reliable results. So instead, we measure per capita GDP, simply because it’s a lot easier to measure.

But by measuring the easier thing, are we really just measuring B.S.? Is per capita GDP really a good measure of living standards? For developing countries, the answer appears to be “yes”.

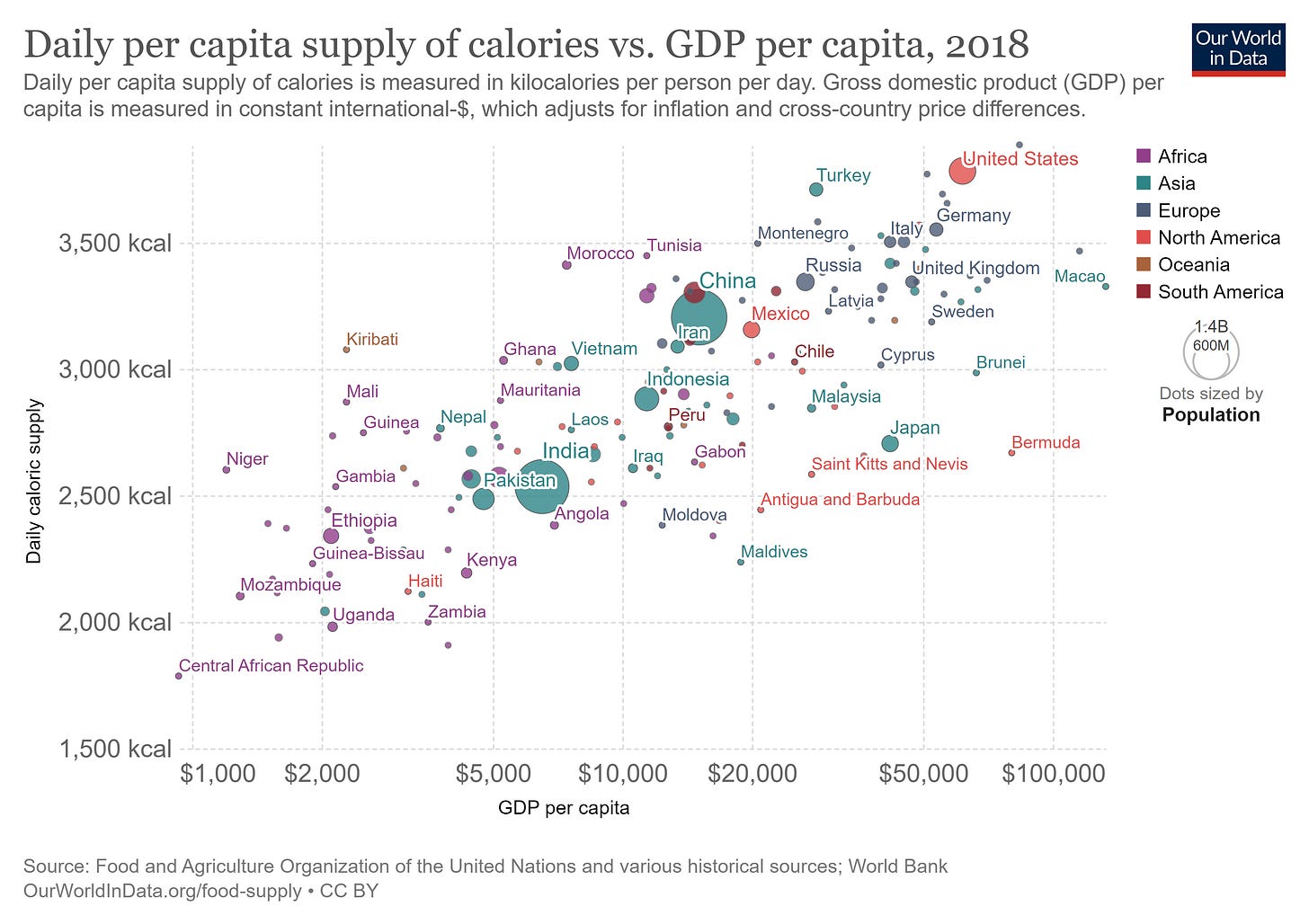

The way we know this is that we can compare GDP per capita to various other measures of well-being whose importance is clear and easy to see. For example, food. Everyone eats food, and one of the big problems for people in very poor countries is how to get enough food. When we look at calorie consumption per person, we see that it’s pretty correlated with GDP — the countries where people get fewer than 2500 calories a day on average are mostly quite poor countries, while the places where people get over 3000 are mostly pretty well-off.

(Note: All of these per capita GDP numbers are measured in terms of “international dollars. This is a measure that tries to account for local price differences, so that 100 “international dollars” can buy you roughly the same stuff in Ghana that it can in Singapore. This approach is called PPP, or Purchasing Power Parity.)

Or take life expectancy. Overall, as countries get richer in terms of per capita GDP, their life expectancy tends to go up. And the countries where people don’t live very long, by modern standards, are all quite poor in terms of per capita GDP:

Or take education. A lot of people think that education is a good thing for a society to have, and when people have the time and resources to send their kids to school it’s generally a good sign. And as with calories and longevity, we see that GDP per capita is correlated with years of education:

In fact, this is why people who tried to come up with alternative, more well-rounded measures of human well-being generally find that these are closely correlated with GDP per capita. The Human Development Index, which includes the measures above along with literacy rates, is a good example.

What’s pretty amazing is that GDP per capita is even correlated with things it was never intended to measure. For example, when you ask people how satisfied they are with life, people in countries with higher per capita GDP tend to give higher answers:

This is why projects like “Gross National Happiness” are unlikely to lead to big advances over GDP in terms of measuring a country’s well-being.

So GDP per capita is a fairly-easy-to-calculate number that is correlated with all kinds of measures of human well-being — food, health, education, and happiness. But on top of that, looking at which countries’ GDP per capita grows a lot over time is a pretty good guide to which countries seem to have become more materially wealthy and technologically advanced. For example, here’s a comparison of the per capita GDP of South Korea, Pakistan, and Argentina since 1950:

This fits with our intuition about how these countries economies developed over the long term. South Korea started out impoverished and devastated by war, but eventually grew into a rich technological powerhouse. Pakistan also started out poor but remains pretty poor to this day. Argentina started out with an income that was impressive for 1950, but which didn’t grow much over time, meaning that Argentina is not considered a rich country today. Google some pictures of the neighborhoods in these countries’ big cities, and you’ll get a decent idea.

In fact, there’s a really great website called “Dollar Street” where you can look at pictures and videos of typical families at different levels of income. GDP per capita isn’t a perfect guide to the income of a typical family (because of inequality), but it’s a rough approximation. Looking through that website, you can clearly see how much of a difference a higher income makes.

Now, I keep saying that GDP per capita is a good measure of living standards in developing countries. What about in rich countries like the U.S., Japan, or France? Here, I think, GDP is still somewhat important, but not as much. The reason is that human beings have diminishing marginal utility of wealth — once we get a decent place to live and decent transportation and a few other basics, things like leisure time and inequality and baseline health become more important. Those things aren’t measured in GDP. And quality-of-life things that aren’t fully reflected in GDP numbers — crime, nice weather, good urban design, and so on — also loom larger.

Anyone who has lived in multiple rich countries — say, Japan and the U.S. — knows that the differences between these countries tend to be more a matter of tradeoffs than raw income numbers. If you want great public transit and low crime and dense urban living and great fashion, go to Japan. If you’d prefer a big house and a lawn and cheap gasoline, come to America. In general these differences are more important than the GDP difference. In fact, if you look at the Human Development Index, you’ll see that all the countries with GDP per capita of over $30,000 are clustered up near the maximum level of HDI.

For rich countries, though, GDP matters for a very different reason.

GDP growth is highly correlated with employment in rich countries

In rich countries, you won’t often hear people talk about the level of their country’s GDP per capita. Instead, you will often hear about growth, which is the percentage change in GDP from quarter to quarter or year to year. In fact, GDP growth is so important in our economic statistics that we just call it “growth”, period.

Why do we talk so much about quarterly or yearly growth in rich countries? The answer isn’t because it represents a big change in living standards; you’re probably not going to notice the difference between an economy at $60,000 per capita and an economy at $62,400 per capita. But nor is it because our politicians and pundits have been brainwashed into an obsession with GDP numbers. The reason is that GDP growth is strongly correlated with employment.

The tight correlation between GDP growth and unemployment is called “Okun’s Law”, and it’s been known since the 1960s. It’s not a law of the Universe, of course, but over time it just keeps being true. Sometimes it looks like the relationship is breaking down, but it generally reestablishes itself:

What’s the reason for this correlation? It’s simple: When people consume a lot and businesses invest a lot, that creates demand for labor, and it also increases GDP.

Unemployment is something that politicians have a big reason to care about, because when unemployment is high, people tend to get quite angry and vote their leaders out of power. Even in countries like China where people can’t vote, a surge of unemployment might create popular anger that threatens regime stability.

So rich-country leaders and media figures have a good reason to talk about — and to care about — economic growth. But it’s certainly not the only thing they care about. As we’re seeing now, inflation, which if anything is exacerbated by fast growth, is the big concern. Very few people were trumpeting America’s fast GDP growth numbers back in 2021, because rising prices were the big pain point.

In other words, critics of GDP imagine that rich-country leaders are obsessed with GDP growth, but this just isn’t true.

Total GDP may be a measure of national power

On top of all these reasons, there’s probably a reason why countries care about their total GDP: It represents one measure of national power.

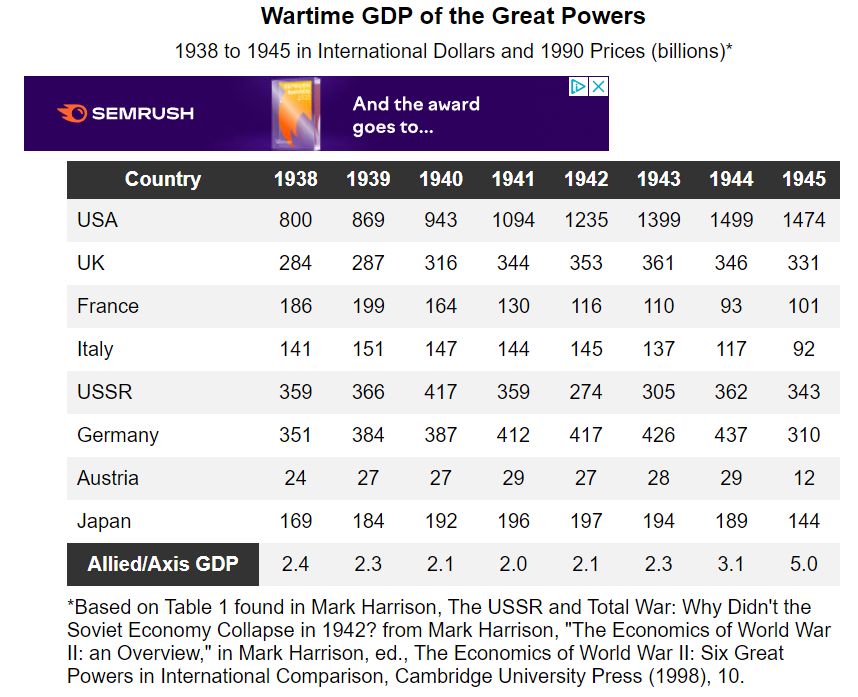

GDP is a successor to an older measure called industrial production (which we still do measure, by the way). The industrial production index was created after World War 1, in response to the observation that the U.S. and the Entente powers ultimately won not by out-maneuvering but by out-producing their opponents. Later, it was replaced with GDP because GDP seemed to give a broader, more comprehensive measure of a nation’s productive potential. Some people do think that GDP proved the decisive factor in World War 2, when unparalleled U.S. manufacturing prowess sustained the USSR and ground down Imperial Japan:

Obviously GDP isn’t a one-number summary of comprehensive national power, but it is one thing to look at. In my post comparing the China-Russia “New Axis” with the U.S. and its allies, I showed how they stack up:

Not everyone cares about national power, but a lot of people — especially national leaders — definitely do care.

So the people who denounce the concept of GDP are, in my opinion, wasting their effort. People in rich countries are not obsessed with GDP; it’s one of many economic numbers they care about, and that’s as it should be. In poor countries, where the overriding goal is basic material security and comfort, GDP looms larger, but that’s also as it should be. There will never be one economic number to rule them all, but GDP is a good and important one, and we should definitely keep it around.

The big adjustor I think that is needed for GDP/capita is some measure of inequality, whether it's Gini index or something more sophisticated. If you want to understand the typical standard of living and so on, *median* income is a good proxy for that; *mean* income, not so much. The issue is worse with PPP/capita: in a highly unequal society, high PPP/capita can end up meaning something like "the rich can employ lots of servants, because servants are cheap", which is a terrible model of economic development. Also, inequality is a very persistent feature of societies, perhaps more so than poverty as captured by aggregate measures like GDP; governments can redistribute to a greater or lesser extent, but it's not a trivial task to do so in the face of elite resistance (including in democracies, where elites can still resist redistribution through propaganda and lobbying).

There's also an argument that GDP from exporting more or less raw natural resources, especially oil, is "fake GDP" in the sense that its contribution to overall economic development is much, much less than the raw dollar amount would suggest. So maybe we need a measure of labour-productivity-based GDP that excludes oil and mining, and then the resource money can be counted separately. Again, in theory the government or whoever controls the resource money can reinvest the profits into general economic development, but in practice few do so in an efficient way; on a spectrum from Norway to Equatorial Guinea, most oil-rich countries resemble the latter more than the former.

It is important to hold the line on standard definitions and uses.

I wondered if those opposed to the use of GDP were degrowthers. The link in the NYT certainly is. It is quite base to try and remove something like GDP from relevance and consideration when you want to destroy what is in it and people know what is in it. But they probably are not all degrowthers.

Still it is for similar reasons some say we are not to concern ourselves with inflation or debt because their policies are going to cause large inflation and debt.

It is like Argentina of old who stopped publishing inflation figures when they became so bad. If you are going to degrow an economy then you will need to hide the collapse of gdp and the recessionary definitions too.