Four reasons Biden's spending bill won't make inflation worse

You can oppose Build Back Better if you like, but don't use inflation as an excuse!

Inflation is still going strong, with the CPI rising at the fastest rate since 1982. I’ll talk more about what to do about that, but today I want to talk about the implications for government spending policy. Republicans are using inflation as a reason to call for the cancellation of President Biden’s signature spending initiative, the Build Back Better bill. Right-leaning economic policy advisors concur. It’s possible that centrist Democratic senators like Joe Manchin — who has warned about the dangers of spending money in an inflationary environment — will go along with this, and quash the bill.

That would be a big mistake. The BBB bill wouldn’t add materially to inflation.

First, before we talk about why this is true, let’s talk about why some people think BBB will raise inflation. One reason is just basic economic theory. Our simple workhorse model of the economy is just aggregate demand and aggregate supply (AD-AS). In that model, increased government spending raises aggregate demand, which boosts growth (and thus boosts employment), but at the cost of higher prices (inflation).

Now, there’s a bit of wiggle room here. It’s not always clear whether government spending is supposed to boost aggregate demand, or whether government deficits are what does it. We’ll get to that later.

But anyway, more sophisticated theories also say that government deficits raise inflation. In fact, there’s a theory called the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level that says that government deficits (including future deficits) are basically the only thing that matters for inflation.

So theory gives some reason to worry about BBB. But the reason people worry probably goes beyond that, into complex sociological and political processes that no one really understands. Some historians believe that the angst over the inflation of the 1970s was due largely to discontent at the way American culture was headed. For example, Rick Perlstein writes:

The conclusion I’ve drawn is that this was a form of moral panic. The 1970s was when the social transformations of the 1960s worked their way into the mainstream. “Inflation spiraling out of control” was a way of talking about how more permissiveness, more profligacy, more individual freedom, more sexual freedom had sent society spiraling out of control. “Discipline” from the top down was a fantasy about how to make all the madness stop.

I wouldn’t go nearly that far. Inflation can hurt real wages (though this is more likely when the main cause of inflation is a supply crunch). It can also cause economic uncertainty that makes long-term planning hard. That makes people mad, and rightly so. But I do recognize that cultural “vibes” and political zeitgeist can make people want to avoid big policy changes, and that inflation can be an excuse for that.

So maybe this post won’t convince people that BBB is safe. But it needs to be said anyway, because in purely economic terms, Biden’s spending agenda poses little to no inflation risk. Here are the four big reasons.

1) The standard theory is woefully incomplete

The AD-AS model tells a very simple story about the economy, but it’s not always the most useful story. The model leads to a Phillips Curve — a tradeoff between growth and inflation — that is often very difficult to observe in real life.

For example, a recent paper by Hazell et al. looks at state-level data and finds that the Phillips Curve is very flat — in other words, not much of a relationship between inflation and growth. That’s a very typical finding. Of course, there are things that lower both inflation and growth — the Great Recession comes to mind. But overall, there’s just a lot of other stuff going on. Some of that can be explained as supply shocks — Hazell et al. judge that the inflation of the 1970s, for example, was due somewhat to the oil shocks (a negative supply shock that fits nicely into the AD-AS model). But the authors assess that the greater part of the 70s inflation was actually due to beliefs about a regime change in monetary policy — people decided the Fed didn’t care that much about inflation, and so inflationary expectations became a self-fulfilling spiral. That’s a story that doesn’t fit very well into the simple AD-AS model.

As for theories like the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level, it’s very hard to test these against data. But when we look at actual relationships between debt/deficits and inflation, we just don’t see much. To see a concrete example of this, look at Japan in the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s. Government debt ballooned to levels unprecedented throughout the rich world, and yet the country spent most of that time at 0 or negative inflation.

Something similar happened to the U.S. in the decade after our own Great Recession. Government debt soared, inflation stayed the same or even fell a bit.

That doesn’t mean fiscal policy doesn’t affect inflation at all. But the lack of a clear historical relationship gives us less theoretical reason to worry.

2) Biden’s bill isn’t very big

The second reason BBB won’t raise inflation is that the bill just isn’t that big, size-wise. Together, the three Covid relief bills in 2020 and 2021 totaled $3.4 trillion — about 8% of two years of U.S. GDP. In comparison, the Build Back Better bill has now shrunk to $1.75 trillion over 10 years, which will be about half a percent of U.S. GDP over that time. In other words, relative to GDP, BBB is 1/16th as large as Covid relief was. Even if you believe Covid relief contributed substantially to the inflation we’re currently experiencing, you probably don’t have to worry about something that’s 1/16th as large. (The U.S.’ annoying habit of listing the size of bills in terms of 10-year totals is really working against Biden here, making BBB seem much larger than it really is.)

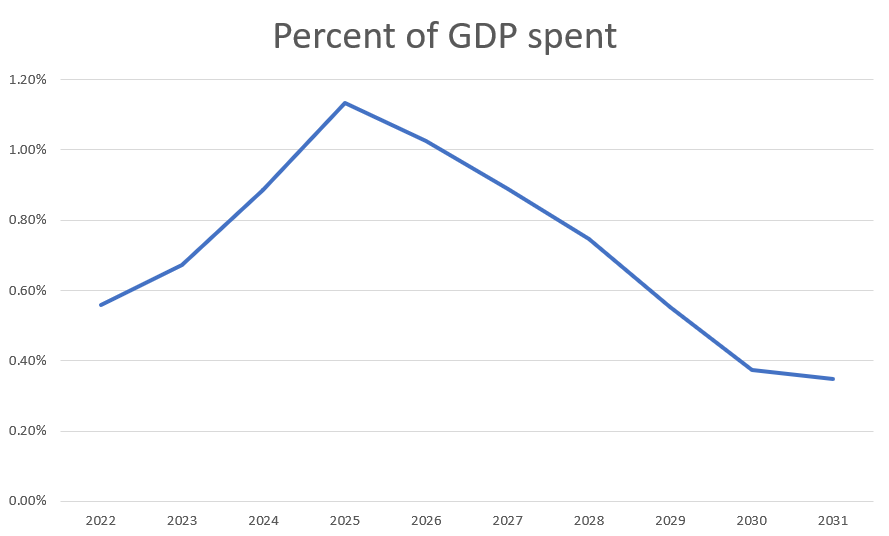

In fact, the Congressional Budget Office produces estimates of spending by fiscal year, so we can look at the size of the bill in each year. Assuming the economy grows at 2% per year, here’s what the BBB bill will spend as a percent of GDP:

Compared to Covid relief, this is really not a big deal, even in 2024-7 when the spending peaks. And Obama’s ARRA stimulus spent about 2.5% of GDP in 2009-10.

So in terms of size, we’re just not talking about very much spending here.

3) Biden’s bill raises taxes

But in fact, spending alone doesn’t tell the tale. In both simple theories and complicated models, it’s deficits that have the biggest effect in terms of raising aggregate demand and pushing up inflation. Yes, it’s possible for balanced-budget spending increases to raise demand — this is called a “balanced budget multiplier”, and it can exist for a number of reasons (e.g. spending that redistributes money from rich people to poor people will raise AD because poor people spend more of their money than rich people do). Mainly, though, when we talk about the danger of inflation we’re talking about deficits.

Biden’s bill some expensive tax cuts (increasing the cap on the SALT deduction being the biggest by far1), but overall it raises taxes. Most of these increases come in 2027 or later. So for the first few years, the CBO predicts that BBB’s impact on the deficit will be approximately equal to its overall spending. But starting in 2027, it will actually cut the deficit!

The knowledge that the BBB deficits — which are fairly modest to begin with — will eventually disappear will dampen the bill’s effect on aggregate demand, decreasing its effect on inflation.

(Of course, this also means the BBB bill will not be much of a fiscal stimulus. But that’s OK; it’s not a stimulus bill, it’s about industrial policy and welfare.)

4) The Fed is managing inflation expectations

So judging by both history and by the bill’s modest size, BBB will have only a minor impact on inflation. So what will have a big impact? Supply chain issues, obviously, but also the Fed. Most economists, and most economic theories, agree that monetary policy is extremely powerful and important when it comes to determining inflation. And U.S. monetary policy is getting tighter and tighter, as the Fed wakes up to the fact that our current inflation isn’t transitory. The Fed is tapering quantitative easing, and will likely increase the rate of the taper very soon. Talk of rate hikes is increasing.

And the tightening seems to be working. The 5-year breakeven inflation rate — a measure of the market’s expectations for inflation over the next 5 years — surged in October and early November but has now come down off its recent highs.

That suggests that the Fed’s tough talk is having the intended effect — reassuring markets that the central bank still cares about inflation, containing price expectations so they don’t spiral out of control.

That doesn’t mean inflation is going to go away soon. To push inflation back to the 2% target in the face of supply chain disruptions, the Fed would have to hike rates so much it would crash the economy. No one wants that. Instead, they’ll merely raise rates enough to keep expectations from rising, and wait for the supply crunch to resolve itself.

And this is one more reason why BBB isn’t going to contribute substantially to inflation. If it passes, and inflation expectations rise, the Fed will simply drop the hammer and raise rates until aggregate demand goes back down to a manageable level. That will cancel out any fiscal stimulus benefits the BBB bill would have — but again, remember that BBB is not about stimulus, it’s about industrial policy and welfare.

Taken together, these factors — the generally mild impact of spending and deficits on inflation, the modest impact of BBB in terms of both spending and deficits, and the Fed’s tightening — mean that BBB’s effect on inflation would be small potatoes indeed. You can oppose the bill if you like, but don’t use inflation as a reason to do so.

The CBO analysis that anticipates a $200 billion deficit impact over 10 years assumes the new and changed programs expire on schedule. E.g., CTC ends after 2022 and SALT cap reinstated in 2025. Alternatively, if BBB policies are made permanent, the CBO estimates a $3 trillion deficit. [1] Such a larger increase in deficit spending would entail a large stimulating effect on the economy.

I think it's well accepted that we put in these expirations with the expectations that the programs would be extended, but we needed to minimize the deficit spending to get this through recon. I haven't seen any proposals from Dem leadership for how we hope to handle that in the future, assuming we even have sufficient Ds in Congress. Hence, I think it reasonable to assume that at least some of these programs will be extended and at least partially paid for through additional deficit spending.

Still agree that the overall impact of BBB on inflation will be minor. Yet, if we truly were concerned about inflation and wanted to use fiscal tools to combat inflation we'd be increasing taxes. Possibly even front loading a tax revenue surplus with later deficit spending in the 10 year plan. That of course would be political suicide.

[1] "Budgetary Effects of Making Specified Policies in the Build Back Better Act Permanent", https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57673

Great article. I've read in the past that the higher rate of unionization in the 1970s could have been a factor, too - that it was the mechanism by which higher expectations (held by unions) got into wages. But maybe this research wasn't accurate.