I’ve been wanting to write a post about how homelessness is primarily an issue of scarce housing, rather than drugs, mental illness, progressive policies, or any of the other factors that are commonly blamed. Then I realized that almost all of the data and analysis that had led me to that conclusion came via Aaron Carr, the founder and executive director of the non-profit watchdog group Housing Rights Initiative (HRI). So I asked Aaron to write a guest post explaining his thesis that homelessness is a housing problem first and foremost. Personally, I find this quite convincing. Even if drugs, mental illness, etc. do exacerbate homelessness to some extent, the success of southern states and cities in curbing the problem suggests that providing ample cheap housing is the best tool we have to reduce the number of people living on the street.

There are few topics I can think of that break people’s brains more than the topic of homelessness. A failure or unwillingness to carefully look at the data has led countless people to believe that the primary drivers of homelessness are drugs, mental health, poverty, the weather, progressive policies, or virtually anything and everything that isn’t housing. And while some, but not all, of the aforementioned factors are indeed factors in homelessness, none of them, not a single one of them, are primary factors. Because if you want to understand homelessness, you have to follow the rent. And if you follow the rent, you will come to realize that homelessness is primarily a housing problem.

So let’s go on a journey in which I will examine the validity of six common claims we hear about homelessness and the solution to our homelessness crisis: housing, housing, and more housing.

Claim #1: “Homelessness is primarily a mental health problem”

The first problem with this claim is plain and simple statistics, namely that the majority of homeless people don’t have severe mental health issues. To the contrary, less than one-third have a severe mental illness. Or to put it another way, while 33% of the homeless population suffers from mental illness, nearly 100% of the homeless population can’t afford housing. 100% is a much bigger number than 33%. Which is why mental health, while a factor in homelessness, cannot possibly or statistically be a lead factor.

Furthermore, if mental health were the main driver of homelessness, places with the most mental illness would have the most homelessness. However, the data shows the exact opposite:

Consider Mississippi, which has among the worst healthcare systems in America, but the lowest homelessness rate. If mental health were a primary factor in homelessness, wouldn’t a state like Mississippi, which catastrophically fails to address mental illness, have among the highest homelessness rates? But it doesn’t.

It was long thought that deinstitutionalization was the primary cause of homelessness, but this theory has largely been discredited. During the height of deinstitutionalization, the vast majority of people who were discharged found cheap housing, because, unlike today, there was a significant supply of it. Additionally, deinstitutionalization was a national phenomenon. So if deinstitutionalization were a primary factor in homelessness, wouldn’t we expect homelessness rates to be somewhat similar across places, since they were all impacted by the same policy? Yet, the data shows substantial variation:

Furthermore, attributing the cause of homelessness to mental health overlooks bidirectionality. While some people become homeless partially due to mental illness, others develop mental illness as a result of becoming homeless.

This shouldn’t come as any surprise. Homelessness is one of the worst forms of physical and psychological torture. Of course being exposed to such inhumane conditions would cause people’s mental health to deteriorate rapidly. The homeless are people. And people do best when they are inside of a toasty home rather than outside in the frigid cold.

So, is mental health a factor in homelessness? Yes. At an individual level, those who experience severe mental health issues may be at higher risk of becoming homeless. But is mental health a primary factor in homelessness? For the reasons stated above, no it is not.

Claim #2: “Homelessness is primarily a drug problem”

Like mental illness, the claim that homelessness is primarily a drug problem runs head-first into a basic stats problem: 20% - 40% of homeless people suffer from substance abuse issues. Or to put it another way, while 20-40% of the homeless population suffers from substance abuse issues, nearly 100% of the homeless population can’t afford housing. 100% is a much bigger number than 20-40%. Hence why drug abuse, while a factor in homelessness, cannot possibly or statistically be a primary factor.

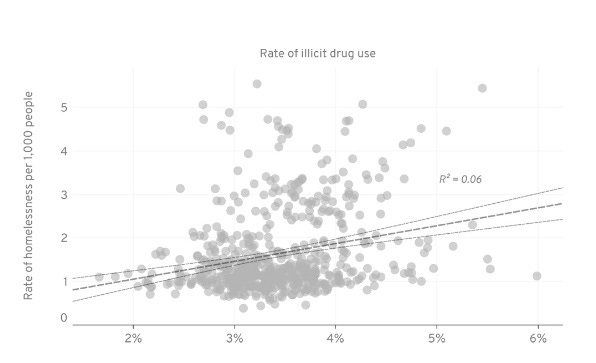

Furthermore, like mental illness, if drug abuse were the main driver of homelessness, it would be reasonable to expect that the places with the most drug use would have the most homelessness, However, the data shows virtually no link:

Take for example West Virginia, which has the single worst drug overdose mortality rate in the country, but among one of the lowest homelessness rates in the country.

And like the claim “homelessness is primarily a mental health problem,” the claim “homelessness is primarily a drug problem” fails once again to consider bidirectionality (which, as you may be starting to realize, is a big problem in homelessness discourse!). While some people become homeless partially due to drug addiction, many others develop drug addiction as a result of becoming homeless:

And why should this come as a surprise? If you are homeless and in a state of mental and physical agony and hopelessness, and someone offers you a temporary reprieve from that (drugs), would you take it? Maybe not. Or maybe so! The point is, for many, if we can prevent homelessness, we can prevent drug addiction.

So, is drug addiction a factor in homelessness? Yes. At an individual level, those who experience drug issues may be at higher risk of becoming homeless. But is drug addiction a primary factor in homelessness? For the reasons stated above, no it is not.

Claim #3: “Homelessness is primarily a poverty problem”

The first thing to understand about this claim is that the vast majority of impoverished people aren’t homeless and will never become homeless. The total number of people experiencing homelessness is less than one-fifth of 1% of Americans, while there are a whopping 34 million people who live below the poverty line.

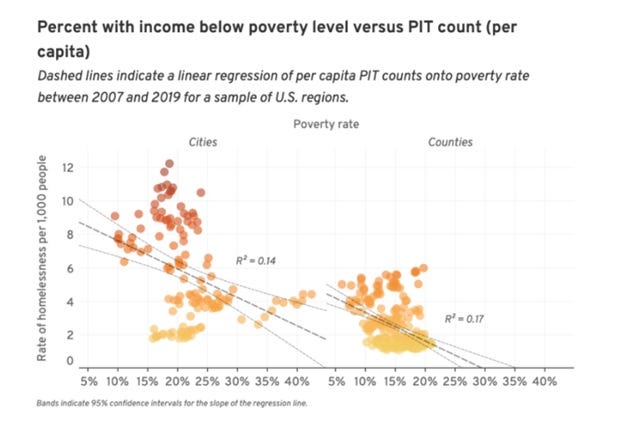

The second thing to understand about this claim is that, just like mental illness and drug abuse, the places with the most poverty don’t have the most homelessness:

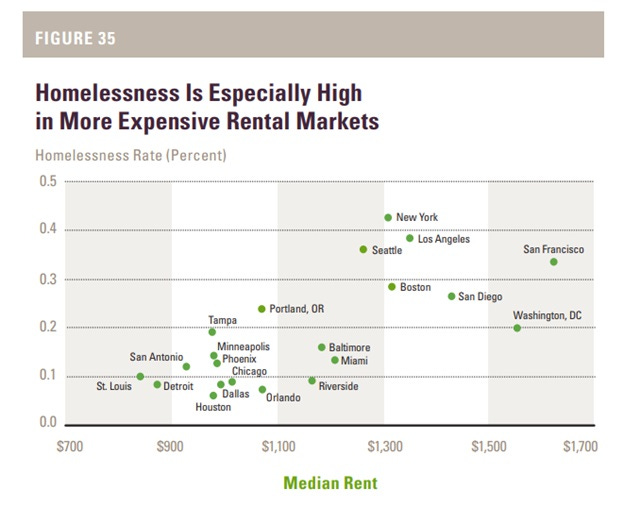

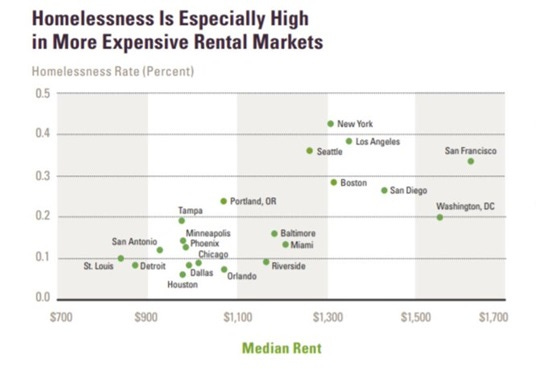

To the contrary, high poverty cities like Detroit (31.8% poverty) have among the lowest homelessness rates in America, while low poverty cities like San Francisco (10.3% poverty) have among the highest homelessness rates in America. When housing costs are low (whether through depopulation or, ideally, abundant housing), homelessness is easier to avoid:

So, is poverty a factor in homelessness? Of course it is. Those who are in poverty are going to be at a significantly higher risk of becoming homeless. But is poverty a primary factor in widespread homelessness? For the reasons stated above, no it is not.

Claim #4: “Homelessness is primarily a weather problem”

Another claim that we often hear in homelessness discourse is that places with temperate climates serve as magnets for the homeless, but there are a few fundamental and fatal problems with this claim.

The first is that in Los Angeles, famous for its temperate weather, 65% of homeless people lived there for more than 20 years and 75% were already there prior to becoming homeless.

And in San Francisco, also famous for its temperate weather, 70% of its homeless population previously lived in the city and a whopping 92% had previously lived in California.

But most importantly, like America in general, California’s modern day homelessness crisis began in the late 1970s, but, as far as I can tell, its nice weather began long before that. In other words, if weather were the primary culprit of California’s homelessness crisis, wouldn’t California have always had a homelessness crisis?

But perhaps I am overcomplicating things. Because all one would really need to do to realize the futility of the weather argument is to simply look at a homelessness map next to a weather map:

As you can see, states like New York, Vermont, and Massachusetts (places not exactly known for their tropical weather!) have among the highest homelessness rates in the country. While some of the warmest places in America, like the South, have among the lowest rates of homelessness rates in America.

So all of this is to say that the weather theory for homelessness is junk.

Claim #5: “Homelessness is a progressive policy problem”

The other claim we often hear in homelessness discourse is that homelessness is being driven by progressive policies, which, like weather, serve as magnets for the homeless.

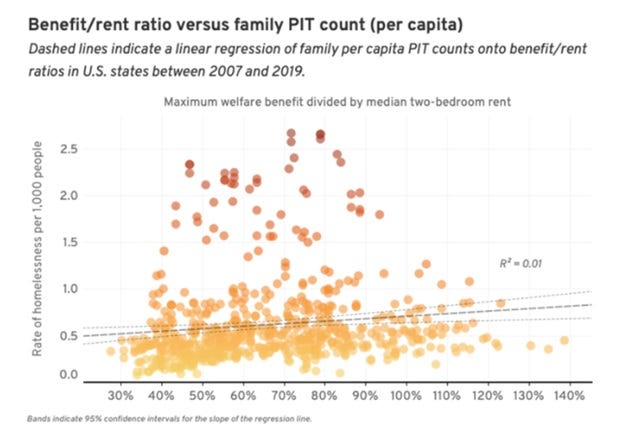

But if this claim were true, wouldn’t the places with the most generous welfare benefits have the most homelessness? But yet again, the data shows no link:

And if progressive policies were the main driver of homelessness, wouldn’t progressive cities have similarly high levels of homelessness? But they don’t. To the contrary, there’s significant variation: Blue cities like Detroit and Chicago have among the lowest homelessness rates in the country, while blue cities like San Francisco and New York have among the highest. Why? Housing costs.

Equally, if the claim that progressive policies were the main drivers of homelessness, wouldn’t conservative places be immune to homelessness irrespective of housing costs (i.e. the main factor that many deny as the primary cause of homelessness)? But, as a general rule, when housing costs go up in red states, homelessness goes up in red states. In the past 10 years, the homeless population of Idaho, a state that Donald Trump won by 30.7%, has increased by a whopping 23%. Why? Because it led the nation in housing cost appreciation.

So while it is true that the places with the highest homelessness tend to be progressive, for the reasons stated above, homelessness isn’t a “progressive policy” problem – it’s a housing cost problem.

Claim #6: “Homelessness is primarily a housing problem”

And, at long last, we have arrived at the actual root cause of homelessness: housing costs.

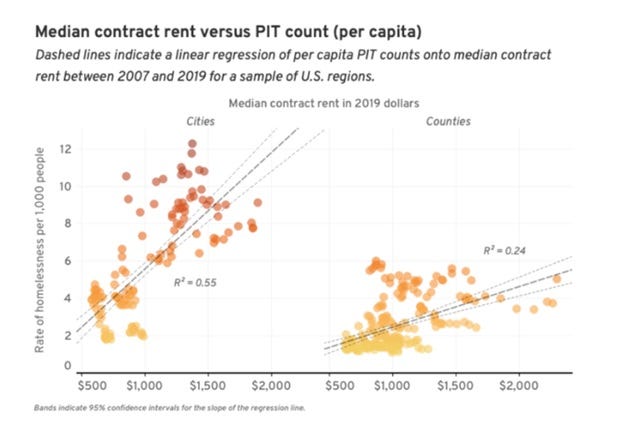

Because unlike poverty and mental illness and drug abuse and weather and welfare benefits and other factors, the places that have the highest housing costs, and the least housing supply, have the largest homeless populations:

In literally any other realm, this would come as no surprise. You can’t have what you can’t afford. If someone says, “I want a $2000 laptop, but can’t afford it,” nobody would find that hard to believe. But if someone says, “I really want the single largest and most crippling expense known to man, housing, but can’t afford it,” for some bizarre reason people would say, “that’s not true!,” or “correlation isn’t causation,” or “homelessness isn’t a housing problem,” or something patently insane. As I said before, the topic of homelessness breaks people’s brains.

The story of homelessness in America is perfectly captured by the following quote in the Economist:

Few Americans lived on the streets in the early post-war period because housing was cheaper. Back then only one in four tenants spent more than 30% of their income on rent, compared with one in two today. The best evidence suggests that a 10% rise in housing costs in a pricey city prompts an 8% jump in homelessness.

And that’s just it: before modern-day homelessness, there was poverty, there was mental illness, there was nice weather, there was welfare, there were liberal places, and there were drugs. So, something must have changed. And what changed were the rents:

If the primary problem of homelessness is housing, then the primary solution to homelessness is housing. And housing is indeed the solution:

● Atlanta reduced homelessness by 40% through housing

● Houston reduced homelessness by 63% through housing

● Finland reduced homelessness by 75% through housing

● Tokyo reduced homelessness by 80% through housing

But as important as housing supply is to reducing homelessness, places like Houston also demonstrate the importance of going beyond it.

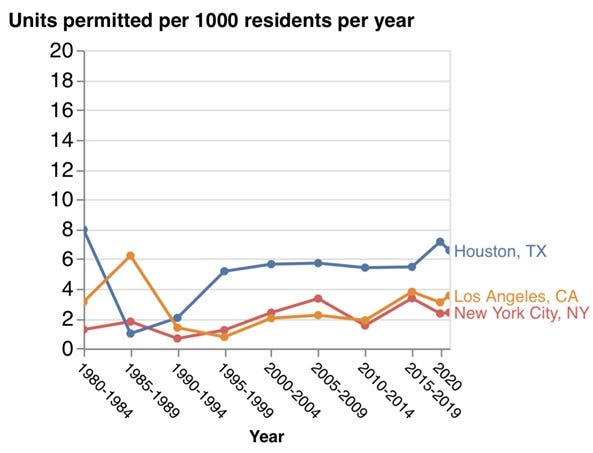

Houston has always had a significantly lower rate of homelessness than other large cities, like New York City and Los Angeles, because unlike those cities, Houston builds a lot of housing:

But despite its ample housing supply, which, as mentioned, resulted in a lower baseline level of homelessness, Houston has still struggled with this problem. And that is because, while housing supply is vital, it will never ever, ever, ever be enough on its own for families who lack income, the disabled, the elderly, and other highly vulnerable populations.

This is why in 2011 Houston started going beyond supply by implementing the Housing First model, which pairs affordable housing with supportive services for people who are experiencing severe mental illness, drug addiction, and other debilitating issues. And, as a result, something incredible happened – homelessness plummeted:

And while mental health and drug addiction aren’t lead factors in homelessness (the vast majority of homelessness is temporary and the vast majority of homeless people just need housing), some homeless people, particularly the chronically homeless (which, again, is a minority of the homeless population), need both housing and supportive services. But if you just give the chronically homeless supportive services without housing, they will still be homeless. Hence why homelessness is primarily a housing problem.

Critics of Housing First will be quick to point to California’s gargantuan homeless population as a failure of the Housing First model. But California’s homelessness crisis isn’t an indictment of Housing First, it’s an indictment of California’s self-inflicted housing shortage and stratospheric rents, which have overwhelmed the Housing First system.

As the data clearly shows, places with the best track records of reducing homelessness do two things: (1) they build ample housing, thereby preventing many cases of homelessness from occurring in the first place, and (2) have ample subsidized housing, which humanely and effectively addresses the homelessness that does occur.

So in conclusion: places with the highest drug addiction rates, highest severe mental illness rates, highest poverty rates, most generous welfare benefits, and the nicest weather don’t have the most homelessness. Places with the highest housing costs do. So we as a society are left with a choice: If we don’t want to solve homelessness, we can continue to misdiagnose it. If we do want to solve homelessness, we can build an ample supply of housing and subsidized housing. There’s no way around this. The solution is clear. And what happens next is up to us.

Josh Murillo and Nick Peters provided outstanding research assistance for this article.

What I see with a lot of these comments is that there's a fundamental disagreement with what the problem of homelessness actually is. It seems like a lot of advocacy groups and policy wonks approach it from the perspective of the problem is that a lot of people don't have reliable shelter and personal spaces. That is the problem from the perspective of people experiencing homelessness.

For most regular people who aren't homeless and don't have close acquaintances who are homeless, that's not the problem at all! The problem is that regular people going about their lives encounter unhygienic individuals who seem to be on drugs or have mental illnesses and are frightening and potentially dangerous to interact with or even have in your proximity. That is the problem that this sub-set of homeless people are creating for non-homeless people. Homeless people who aren't like that are not part of "the homeless problem" and one might in a general sense wish their situation were better, but their problems are their own, not everyone else's problem.

And yes, you could say that solving the first problem by reducing the cost of housing will eventually impact the second problem, but the scary, unhygienic, mentally ill people that are the "the homeless problem" will be among the last people to come off the streets. It's a "bank shot" solution that promises that solving this first problem that is not that important for many regular people will eventually over a long period of time help with the second problem that is important to non-homeless people. Normally that sort of "bank shot" is the hallmark of conservative policy solutions. "You see, if we cut taxes that will spur innovation and create a more productive society which will raise the standard of living and in the end everyone will be better off than if we had kept the tax money and used it on public assistance" If you don't find that convincing, you might consider why "if we reduce the cost of housing then all the scary, smelly people will no longer be in public spaces" isn't very convincing.

Of course I think reducing the cost of housing would benefit a lot of people who aren't homeless, but then you can sell it that way rather than making a bunch of promises about how it will get unhygienic people who are alarming to interact with out of public spaces.

Makes sense to me. I think we have to ask ourselves what is visible versus what is.

Back in the 90's, I remember a census was done of 'subway beggers'. That used to be a big thing in NYC and while one might guess most were homeless, that may or may not have been the case. Anyway, people thought the number of subway panhandlers would be in the thousands, maybe even tens of thousands. When the census was done, it was absurdly low, like 75 people or so! The impression of their large numbers came from the fact that they rode the subways all day so were visible for millions of people day in day out.

Likewise the mentally ill homeless person can draw a lot of attention. In NJ we had an infamous homeless person who was kicked out of the library and got a large settlement...only to remain homeless and harass people on the street.

But the person who may work changing tires or at Wal-Mart who may sleep in their car or crash on a friends couch or use his shower in the morning maybe far more common and much less visible to the general public because he isn't begging on the street or exhibiting mental illness in public.