Economic development is doing OK

Poor countries aren't catching up as fast as we'd like, but they're catching up faster than before.

I recently did a series of posts highlighting the successful industrialization and rapid economic growth of countries like India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Poland, and the Dominican Republic. And I didn’t even include China, which is the most amazing of the recent development success stories. So I was a little surprised to read David Oks and Henry Williams write an article called “The Long, Slow Death of Global Development”, and I was even more surprised to see my favorite podcast, Odd Lots, embracing this thesis rather uncritically. It seems extremely clear to me, witnessing the abundance of success stories, that global development has not been dying any sort of death — long, slow, or otherwise.

But, economic theses are made to be argued about, and I’m sure a debate will get us all thinking hard about how poor countries can get rich faster. So let’s dive in.

Writing about “development” is difficult, because that word can mean several different things:

It can mean income growth and poverty reduction among poor countries.

It can mean convergence (i.e., economic catch-up) between poor and rich countries.

It can mean industrialization, i.e. a structural shift from agriculture to manufacturing, which is a common feature of how countries get rich.

Also, there’s the question of what time period we’re looking at. Are we looking at development over the past 30 years, or the past 5? Or are we looking at future projections, and the possibility of continued development? There’s also the question of levels vs. growth rates — should we be happy that Bangladesh is much less poor than before, or should we despair that it’s still pretty poor? And there are also different regions — should we look at the average of the whole developing world, or should we focus on specific regions like Africa or Latin America?

It’s easy to get confused between these different questions. The Oks & Williams article has a tendency to skip back and forth between some of these different questions, so that despite the authors’ good-faith attempts to weave disparate points into a cohesive whole, it can be difficult to isolate what their theses are. But basically, I think they’re making three claims:

They’re telling a story about the history of development, arguing that 1950-1980 was the peak, and recent decades have been much worse.

They’re offering a theory about the mechanisms of development, arguing that industrialization is no longer a viable path for poor countries.

They’re making a prediction about the future of development, arguing that there are significant headwinds that will slow poor countries’ growth.

I’ll address each of these in turn. First, I’ll tell my preferred story of the history of economic development since World War 2, and why the last three decades have been the closest thing we’ve had to a golden age.

The last three decades have been the golden age of development

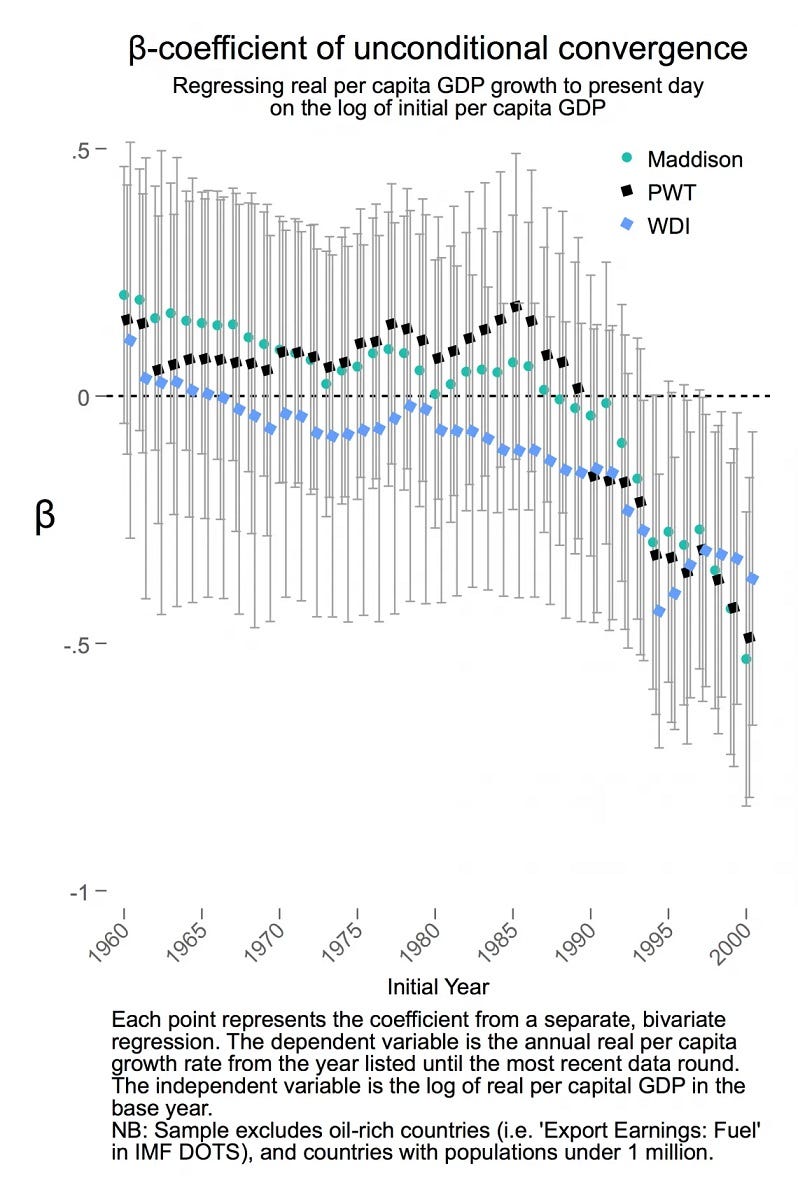

My basic story of development, which I wrote about in this post two years ago, starts with a 2021 paper by Patel, Sandefur, and Subramanian. Basic economic theory says that poor countries should grow faster than rich ones, but up through 1990 this didn’t seem to be happening — the rich countries kept staying ahead or even pulling away. Exceptions like South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore were few and far between. But around 1990, Patel et al. find that things flipped — suddenly, there was a negative correlation between a country’s income and its growth rate, just like economic theory says there should be. The poor countries were finally catching up.

A negative value on this graph means a more negative relationship between growth and income; it means that rich countries grow less quickly than poor countries.

Note that this shift is definitely not just China. Each data point in these regressions is a single country, so China is just one data point among many. On average, poor countries started catching up to rich ones over the last three decades.

Nor are these the only economists that find this effect. Here are Kremer, Willis, and You (2021):

[T]here has been a trend towards unconditional convergence since the 1960s, leading to convergence since the early 2000s…[P]olicies and institutions have converged substantially, towards development-favored institutions - those associated, across countries, with higher levels of income.

So any account that claims that development has been dying a long, slow death needs to come to grips with the fact that poor-country catch-up growth was basically nonexistent in the postwar decades, but has been a fact of life in the 21st century so far.

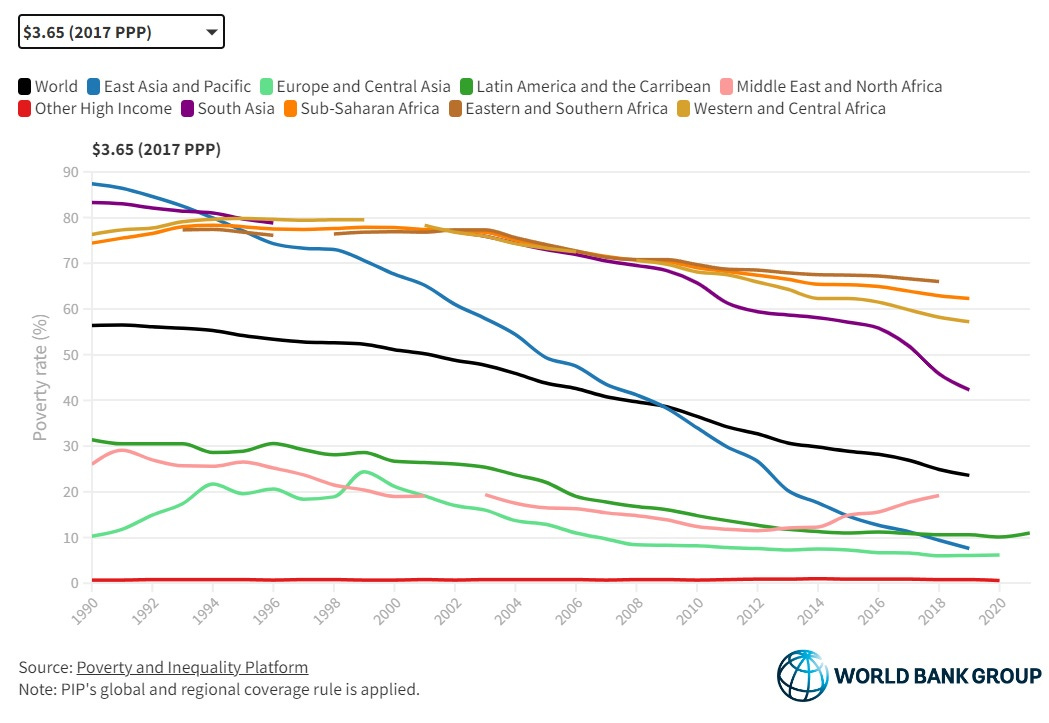

This accelerating poor-country growth was accompanied by massive poverty reduction. People like to argue about whether “extreme poverty” — measured as people living on less than $2.15 a day — is an appropriate threshold. Personally I think lower thresholds are more important than higher ones — going from the edge of starvation to food security is more important than, say, getting a motorcycle. But this debate really doesn’t matter, because if you look at all three of the poverty thresholds defined by the World Bank — $2.15/day, $3.65/day, and $6.85/day — they have all been going down almost continuously in all regions of the world for two to three decades. Here are the three charts:

Obviously, East Asia’s poverty reduction has been the most impressive, due to China’s hypergrowth. But with the exception of the Middle East since the mid-2010s (which was torn by wars), all regions have experienced some drop in poverty rates — no matter how you want to measure it.

I’d especially like to highlight India here, because it’s the world’s largest country and it’s still quite poor. Even using the more conservative estimates of Indian poverty reduction, the drop has been nothing short of staggering:

Anyway, these numbers show that Oks and Williams are on very shaky ground when they claim that the postwar decades were the golden era of global development:

[I]t was the period lasting roughly from 1950 to 1980…that stands in retrospect as a golden age for the cause of global economic development…[T]he global economy underwent an economic boom of an intensity and duration never seen before or after…For the countries of the poor world, this meant three decades of vigorous growth, with rapid industrial expansion[.]

Yes, the world economy experienced rapid growth during the postwar years. But poor countries failed to catch up with richer countries. And even though growth reduced poverty rates, high birth rates and high inequality meant that the total number of extremely poor people in the world actually increased during this “golden age”. Only in the mid-1990s did the number of human beings in extreme poverty actually begin to fall.

And anecdotally, it’s just very hard to call the years of China’s Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution and India’s ultra-slow growth a “golden age” of development, when those two giant countries together accounted for over half of the developing world.

In other words, if global development has ever had any sort of a golden age, it has been the last three decades, not the postwar years.

Now, a word of caution. The sea change since the mid-90s has been a massive human triumph, but it’s crucial to emphasize that this is just the start of a long journey. Despite its rapid growth and its success against extreme poverty, for example, India is still quite a poor country overall — most of the people there are still living on less than $7 a day. And in fact, this is typical. Even the economists who find that convergence is now underway caution that it’s still proceeding at a slow pace. There are a few countries like Poland and Malaysia that have approached developed-country status in recent years, but overall the rich countries remain a pretty rarefied club. So global development isn’t even close to the finish line of “every country gets rich”, even in the regions that are catching up the fastest.

But overall, I would tell a very different story about the history of global development than Oks and Williams tell. As I see it, development was always very difficult, unreliable, and uneven. But it has been a little less difficult, unreliable, and uneven in recent decades than it ever was before. Development’s story has not been that of a fall from grace, but of a slow, fitful acceleration.

That story, however, leaves a key question unanswered: Can the (relatively) good times continue?

Industrialization probably isn’t over (and we don’t know til we try)

The second big argument that Oks and Williams make is that industrialization — getting rich via manufacturing — is not a viable development path for most of today’s poor countries. They allow for exceptions, like some of the ones I named above (Poland, Vietnam, etc.). But overall, they claim that this road is closed:

Our relatively pessimistic assessment of the progress of emerging markets is shaped by a judgment about the fundamental role that manufacturing plays in economic development…For most of the world, there is no real path to development that does not run through manufacturing…[But] the countries of the poor world thus find themselves today in a situation markedly different from those of successful late-industrializers of the past.

Why? Basically, they base their case on two things: 1) Dani Rodrik’s observation of “premature deindustrialization” in some parts of the developing world, and 2) speculation about factors that might disrupt the traditional model of industrialization.

First, let’s talk about Rodrik. In a 2015 paper called “Premature Deindustrialization”, he argues:

[C]ountries are running out of industrialization opportunities sooner and at much lower levels of income compared to the experience of early industrializers. Asian countries and manufactures exporters have been largely insulated from those trends, while Latin American countries have been especially hard hit.

Already we can see one big caveat to the thesis: it doesn’t seem to have hit Asia. Asia has 60% of the world population, and an even larger fraction of the developing-country population, so saying that countries have been deindustrializing except for Asia is a little like saying “Other than that, Mrs. Lincoln, how was the play?”.

Second, much of the deindustrialization that Rodrik documents happened far in the past — as he puts it, the trend is “not very recent”. In Latin America, Rodrik’s starkest example, deindustrialization was already happening in the 1960s — right in the middle of the period that Oks and Williams call the “golden age” of development! For Sub-Saharan Africa, deindustrialization seems to have started in the 70s or 80s, but it’s hard to tell because the data is patchy.

But anyway, let’s think about what this means. In the years since Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa began deindustrializing, much of East and Southeast Asia and East Europe (including Turkey) have pursued a successful strategy of manufacturing-led growth. So it’s clear from just a quick reading of the historical record that the deindustrialization of Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa did not herald some great economic shift that made industrialization impossible.

Rodrik posits that changes in the economy make it harder for countries to industrialize nowadays. I’ll address that idea in a bit, but first let’s examine the magnitude of the effects that Rodrik posits. He argues that before 1990, manufacturing tended to peak as a share of a country’s economy at about $49,000 of GDP, but since 1990, manufacturing has peaked as a share of a country’s economy at about $22,000:

OK, suppose Rodrik is right and that’s just the way the world is now. That still means that industrialization can potentially take countries all the way to $22,000 of per capita GDP! In 1990 dollars, no less! Given that India is now at $7,000 and Nigeria is at $5,400, I’m not particularly discouraged by that $22,000 number. My reaction is: OK first let’s get the poor countries to $22,000, then we’ll talk.

Now let’s take a look at Rodrik’s theory of deindustrialization. Oks and Williams write that automation is a big reason why poor countries can no longer industrialize. And they attribute this idea to Rodrik:

As Rodrik and others have pointed out, each wave of industrialization has been weaker than the last: possible factors include heightened global competition, with contemporary countries having less control over their home markets than did successful industrializers…global shifts in demand…and, perhaps most importantly, the decline of manufacturing labor intensity due to labor-saving automations, which may accelerate in coming years[.] (emphasis mine)

But taking a look at the model in Rodrik’s paper, we find that automation — represented by rapid total factor productivity growth in manufacturing — actually helps poor countries industrialize, even though it does the opposite for rich countries:

This last set of [theoretical] results is important in interpreting the experience of developing countries that have experienced rapid deindustrialization. These countries tend to be small in global markets for manufacturing, so we can take treat them as price takers. What equation (9) shows is that employment deindustrialization in those countries cannot have been the consequence of differentially rapid TFP growth in manufacturing at home. That kind of technological progress would have fostered industrialization, rather than the reverse. In this respect, developing countries are quite different from the advanced countries where there is considerable evidence technological progress was the culprit. (emphasis mine)

Rodrik’s model says that deindustrialization in poor countries would have to be a result of a slowdown in the demand for manufactured goods from rich countries, rather than a consequence of robots taking poor people’s jobs. (The reason for this, in the model, is that poor countries are assumed to be mostly exporters, so if you automate manufacturing in poor countries you can always just sell more on the global market instead of firing workers.)

Now, that’s a very simple model, and I doubt Rodrik himself believes that it represents all that’s going on. For example, it doesn’t include local multipliers, which could model how manufacturing can support economic growth even without generating much employment. But I digress. The real point here is that Oks and Williams have greatly overestimated the degree to which Rodrik’s paper supports their thesis that industrialization is no longer possible.

Other than Rodrik’s paper, Oks and Williams basically rely on a narrative interpretation of why East Asian countries were uniquely able to industrialize:

[P]oor societies today are also quite different from previous…industrializers. South Korea in 1960 or China in 1980 were largely agrarian societies, with vast peasantries (“full of potential energy, waiting to be released,” as Perry Anderson has written) under uncontested rule by flawed but coherent coalitions of developmental elites. Their initial success was a product of high state capacity even at low levels of income, itself the product of a variety of factors: these countries enjoyed state autonomy from rentier interests, owing to the displacement of rural landlords, as well as strong state monopolies on violence, founded on durable social fabrics; national elites could coordinate effectively between state and enterprise, able not just to subsidize firms but to discipline them as well; their workforces were relatively skilled and healthy, due to successful education and public health policies, and included an abundance of cheap workers who could flood into manufacturing.

I don’t discount any of these factors, but the idea that these are necessarily unique to East Asia is…well, it’s very hand-wavey. “Durable social fabrics” and the “potential energy” of the peasantry are basically varieties of economic phlogiston — labels for some sort of general mojo that fill the gap when there’s nothing we can really measure. (“State capacity” is a measurable thing in some cases, but in this case it’s sort of a placeholder as well.)

This is basically a way of saying that East Asian countries were able to industrialize because they were politically able to do the policies that led to industrialization. Well, OK. Good job! But why should we assume that, say, African societies are unable to move in this direction — to make their social fabrics more durable, to make their workers healthier and more educated, to establish strong state monopolies on violence, etc.? Oks and Williams say a lot of pessimistic things about the state of African politics and society, but we’ve heard all these things before — corrupt extractive elites, violence, instability, etc. If we just assume that those problems are here to stay, then maybe we should throw up our hands and give up on Africa. But I’m just not willing to do that yet, especially given how chaotic and dysfunctional, say, China looked half a century ago. Countries can change, and if you think they can’t, why are you giving policy advice?

Anyway, there’s an obvious alternative to the idea that robots and globalization have made manufacturing-led impossible for anyone who doesn’t have the political and social mojo of East Asia. It might be that the world can’t all industrialize at the same time — that some countries naturally tend to specialize in being natural resource exporters, selling energy and minerals and food to everyone else, even as some other countries join the ranks of the manufacturers. This is, in fact, the upshot of the economic geography model of Krugman, Fujita and Venables, when applied to global trade networks and global development. In that model, global regions industrialize one after another, with a shrinking “periphery” region selling natural resources to the rest.

If this model holds, then the real reason Latin America and Africa deindustrialized was that other countries got ahead of them in line. When all the world’s manufacturing investment and demand is flowing into China, it’s probably just a better idea for Brazil or South Africa to sell China minerals and food instead of trying to compete with Chinese factories.

But now that China’s industrialization is slowing down, other regions could get their chance. Already, lower-end manufacturing is flowing out of China to Southeast Asia and South Asia, just as it once flowed from America and Japan and Europe to China. Perhaps that will create another commodity boom to enrich Africa and Latin America and the Middle East. And perhaps after that boom is done, in 30 or 40 years, manufacturing will flow to Africa.

I have no real idea if this is how the world works. Oks and Williams sort of wave the idea away, saying that “an international “queue” for industrialization…may no longer hold.” But it may still hold! And the current success of Vietnam, Bangladesh, and a few other countries getting started on the road to industrialization offers hope that if other poor countries can get their acts together policy-wise — I’m looking at you, India — they can still tread some modern approximation of the well-worn path of industrial development.

Maybe it won’t work. But I don’t think Oks and Williams have made a convincing case that it isn’t worth trying.

Is global growth going to crash?

Oks and Williams’ final big thesis is that poor countries are about to face a bunch of big headwinds:

Stagnant development in most of the poor world, ecological crisis, declining populations in the developed world, and growing populations in the worst-off places—what will this explosive mixture yield? With aging populations in the United States and Europe, and the Chinese economy apparently entering a low-growth equilibrium, the prospects for another global commodities boom to rescue poor economies seem distant.

Even if industrialization is still possible, it’s going to be hard to do if your country is roasting to death or under water. Climate change is a severe challenge that the entire world will have to deal with. But what Oks and Williams overlook is how we’re going to deal with it. We’re going to fight climate change by building a ton of green energy and green transportation and green infrastructure. In the U.S., the Inflation Reduction Act is already spurring massive investments in energy, manufacturing, and infrastructure. Other countries will follow suit. And what China’s doing dwarfs all other countries’ efforts.

This massive investment is going to create a lot of demand for cheap manufactured products from poor countries, which could help spur industrialization. But it’ll also spark a commodity boom. Maybe oil and gas and coal won’t be in such high demand (and that’s a good thing!), but metals sure will be. That will give the resource exporters somewhat of a boost.

Demographics are a more dicey proposition. Shrinking rich-world populations (including China) will indeed dampen demand for poor countries’ products. And continued population growth in Africa — despite falling fertility — will put a strain on those countries’ living standards, since they’re still natural resource exporters, and larger populations mean fewer resource revenues per person. So I do think this could slow development somewhat. But on the other hand, demographic dividends from falling fertility in industrializing nations — especially in South and Southeast Asia — will give these countries a boost.

There’s another potential big factor that Oks and Williams don’t discuss, which is decoupling. The IMF is worried that an economic rift between China and the developed democracies will make it harder for poor countries to sell their products, because they’ll have to choose one market or the other. But I don’t expect this to happen — only a few products will be under export controls. And I think pressure on multinational companies to “friend-shore” production out of China could give a major boost to manufacturing-led growth throughout the remaining poor countries of Asia — already Apple is moving some operations to India, to name just one example.

In general, I think global growth is a very hard thing to forecast — even when the professionals do it, it involves a whole lot of tea-leaf reading. But simply looking out at the world and being pessimistic because of climate change and low fertility is not sufficient reason to think that economic development is dying.

So basically, I think Oks and Williams’ three main theses either miss the mark, or rely on a very hefty amount of speculation. Global development has definitely not been dying a long, slow death, nor is there good reason to believe that industrialization will longer work, nor should we be overly confident in global macroeconomic forecasts. The proper perspective here, I think, is to realize that economic development was always hard, and always slow, and always uneven and uncertain. We were right not to despair in previous decades, and we shouldn’t despair now.

I disagree with Noah, I think he's too bullish on Africa, specifically Sub-Saharan Africa. To quote a recent post on AE

"from 1960 to 2021, real per capita GDP grew 46 times in China, over 5 times in India, 158% in Latin America, and only 40% in Subsaharan Africa. In a closer time period, from 1990 to 2021 CEE countries increased their real per capita GDP by 144% (starting from a much higher point as well) while SSA, again, only grew by 24%."

A lot of the countries that had major issues in the past but ended up successful, like China, Taiwan, Korea, still had existing systems, people, culture, and foreign factors that could be turned to facilitate economic growth.

Currently a lot of SS Africa is like 'Haiti-lite' where nearly everything on every level has been utterly disorganized and corrupt for decades; there isn't really a place to start without a total reorganization of everything, or a miracle. It also feeds on itself; being surrounded by corrupt, poor, and unstable states is not conducive to success.

South Korea's growth has continued strong, but Taiwan's has slowed down in recent decades. Why has Korea been able to keep growing incomes fast when Taiwan has slowed?

I don't want to exaggerate the comparison. Taiwan's growth is still equal to or faster than developed countries, and Korea, while growing faster than today's Taiwan, is still far from the rocket-speed growth both countries had in the 1980s. But these are economically two very similarly positioned countries. You'd think they'd face the same laws of economic gravity. Yet Korea somehow has been able to sustain above-trend growth for 20 years longer than Taiwan.

"How countries get rich" attracts one-size-fits-all explanations, but in this case we have two countries, both growing, but obviously with some kind of important difference to Korea's benefit. If there was a reason for Korea's recent outperformance over Taiwan, it'd be worth knowing.

Noah, any ideas?