Don't worry about de-dollarization

It's not going to happen. Though to be honest, a little would be a good thing.

A number of financial pundits are publicly worrying that the sanctions on Russia will lead to a post-dollar world. The basic idea here is that with Russia essentially cut off from financial transactions with the West, it will either turn toward deeper financial integration with China or toward the use of trans-national commodity currencies like gold and Bitcoin. And if that movement leads other countries to follow, then either the yuan, gold, or Bitcoin might become the global currency, and the U.S. might eventually find itself financially isolated instead of Russia. For example, over at the Financial Times, Rana Foroohar writes:

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine [will result in] a quickening of the shift to a bipolar global financial system — one based on the dollar, the other on the renminbi…[T]his supports China’s long-term goal of building a post-dollarised world, in which Russia would be one of many vassal states settling all transactions in renminbi…[T]he Chinese hope to use trade and the petropolitics of the moment to increase the renminbi’s share of global foreign exchange…Beijing is slowly diversifying its foreign exchange reserves, as well as buying up a lot of gold. This can be seen as a kind of hedge on a post-dollar word [sic].

Bitcoin boosters, meanwhile, naturally think the new global currency will be BTC.

To be blunt, this is unlikely to happen. Neither the Chinese RMB, gold, or Bitcoin is prepared to play anything like the role that the dollar currently plays in the global financial system. I’m not being contrarian by saying that, either — most of the top economists surveyed by Chicago Booth’s IGM Forum don’t think a shift away from the dollar is likely.

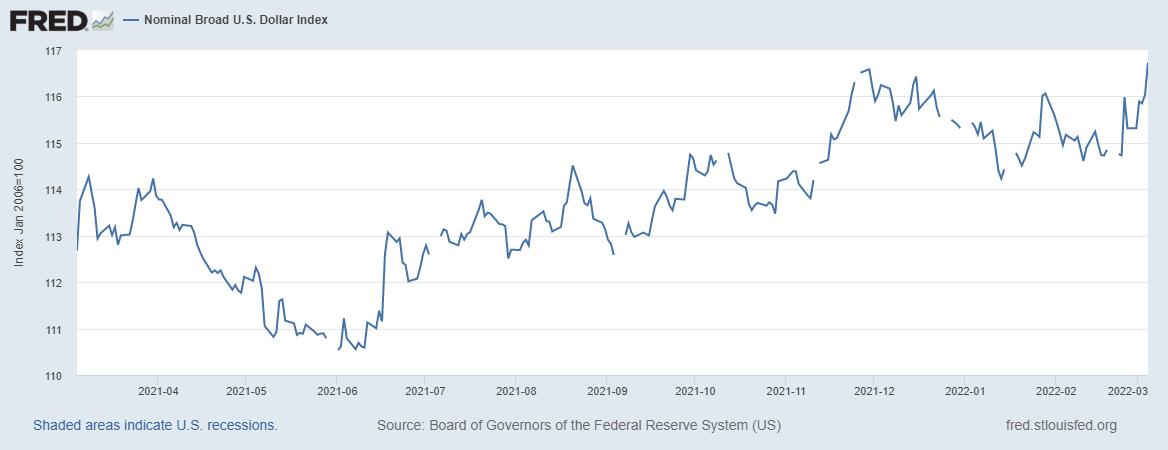

And markets seem to be even less concerned. The U.S. dollar’s value relative to the currencies of its trading partners actually rose after the sanctions, suggesting that confidence in the dollar is unshaken:

But although I may not be taking a bold contrarian stance here, it’s still worth it to explain why de-dollarization is highly unlikely to happen as a result of these sanctions (and why it’s also not as terrifying a prospect as people think).

Before I explain that, by the way, I should say that I do have some qualms about the way sanctions have been employed in this conflict. I think that wholesale destruction of a country’s economy is not generally an effective way of pressuring a repressive or aggressive regime to change its behavior, as Iran, North Korea, Cuba, and many other cases have clearly shown. I think sanctions should be focused on weakening a country’s military machine, not on impoverishing its populace — otherwise, by enraging the people against an external enemy, sanctions risk entrenching the very regimes they seek to weaken. I also do worry that there could be a slippery slope, in which ultra-harsh sanctions of the kind being used against Russia eventually get deployed in conflicts where the morality is not nearly so cut-and-dry.

So there are risks to these sanctions, I think. But de-dollarization is not one of them — at least, not in the current conflict. The first reason this is true is that the kind of financial shift people are worrying about would have to mean not just abandonment of the dollar, but also abandonment of the second most important international currency — the euro — at the same time.

De-dollarization would really mean de-dollar-and-euro-ization

The first thing to note about the financial sanctions on Russia is that they’re mostly about making it harder to use euros, not dollars. As of June 2020, Russia’s foreign exchange reserves were:

30% euros

22% dollars

23% gold

12% yuan

So when Western banks blocked the Russian central bank from making transactions, this was more about euros than dollars. And even more importantly, Russia traditionally imported a lot more from Europe than it did from the U.S.:

Remember, to import from a country, you need that country’s currency — American businesses get paid in dollars, eurozone businesses get paid in euros. So Russia had a lot more need for euros than it did for dollars. The current sanctions are therefore going to impact euros even more than dollars.

And remember that together, the dollar, the euro, and the currencies of other countries participating in the sanctions effort against Russia overwhelmingly dominate the composition of international reserves:

The yuan (RMB) is miniscule. (Gold isn’t included here but I’ll get to that in a bit.)

So to shift the financial system away from the currencies of the bloc of nations now putting sanctions on Russia would be an absolutely monumental undertaking. And none of the candidates to replace the current system really make sense.

Why the yuan isn’t ready to replace the dollar

The best alternative to replace the dollar would be the Chinese RMB (yuan). China represents around 18% of the world economy, and about 15% of world exports, so countries have plenty of reason to use the yuan. China is also a high-tech country with well-developed systems for banking and payments, so it would have no trouble handling the technical aspects of making the yuan the global reserve currency.

There’s just one problem: Capital controls. China has a lot of rules that make it very very hard to sell yuan for foreign currencies. And it’s not just about the current rules — there’s also a general awareness that if capital ever tries to leave China in any significant amount, the government will impose a bunch of new rules in order to stop it. This was vividly demonstrated in 2015-16, when a stock market crash caused a massive capital flight from China, but the government stanched the outflows by tightening up capital controls significantly.

Why does China make it so hard to get money out of China? One big reason is that this is necessary in order for China to control the value of the RMB. When capital flows out of China, it puts downward pressure on the currency, which makes it harder for Chinese companies to afford inputs and for Chinese consumers to afford imports. But when capital flows into China, it raises the value of the yuan, which makes it harder for Chinese exporters to sell goods overseas — since China traditionally has a mercantilist economic policy, this is something it wants to avoid.

So by becoming the international reserve currency, China would give up its control over the value of its currency, exposing it to both unwanted appreciations and unwanted depreciations.

Now, it’s possible that China will change its attitude here, as the U.S. changed our attitude toward international finance around the time of the world wars. The country’s leaders could decide to be less mercantilist and less control-freaky about their finances, in exchange for global leadership. Would it then be possible that countries like India and other emerging markets might migrate into a yuan bloc?

Unlikely. Because now that the U.S. and Europe have shown the power of financial sanctions, there is precisely a 0% chance that China would avoid using this weapon if it could. Whatever the West is willing to do in order to punish its adversaries, China would definitely be willing to do.

Implicit in the idea that sanctions would drive the world to join a China-centric financial bloc is the notion that China would somehow be a more benevolent financial hegemon, less likely to wield its power to punish nations for doing things it doesn’t like. And that notion is complete, pure, grade-A nonsense. Remember, China is the nation that just threatened to retaliate against Czech companies simply because a Czech politician paid a visit to Taiwan.

Joining a China-centric financial bloc will not save countries from the threat of economic coercion — it will vastly increase that threat. So don’t expect to see countries join such a bloc unless they’ve already been forcibly exiled by the West.

Why gold isn’t ready to replace the dollar

OK, so let’s talk about other possible substitutes for the dollar-euro. You’ll notice that gold isn’t included in the IMF’s chart of forex reserves above. In fact, gold is still a significant reserve asset, representing a little less than 15% of the total as of last year.

BUT, guess who holds most of that gold. Yep, it’s the “advanced” economies, i.e. the European and Asian countries putting the sanctions on Russia.

The U.S. itself is by far the biggest holder. (In fact, this fact is one thing that helped the world transition from a gold standard to a dollar standard after the world wars — for a while, those two things weren’t even that different.)

Of course, this doesn’t preclude the switch to a global gold standard, since most of the gold in the world is in private hands. But since gold can’t easily be carted around (this isn’t Dungeons & Dragons), this means that gold-based payments — whether the transfer of ownership rights over gold, or payments in some asset whose value is linked to gold — have to be handled electronically. And that means banks.

And who controls banks? National governments. The U.S. doesn’t have to own gold itself in order to tell Chase and Wells Fargo and Citibank how to handle gold-based payments. It can just do that. And China can do the same to its own banks, and Germany to its own banks, and so on. Which means that using gold for international payments isn’t really a way of immunizing yourself against the kind of sanctions deployed against Russia.

What we could see is a shift toward countries holding gold reserves, as a way of hedging against the possibility that the West might hit them with sanctions. In fact, Russia did this after 2014, and some other countries might do it too. But as I’ll explain later, this wouldn’t be such a bad thing.

But first, Bitcoin.

Why Bitcoin isn’t ready to replace the dollar

Bitcoin boosters frequently claim that Bitcoin will replace the dollar. But this will not happen.

First, let’s point out that people don’t expect anything like this to happen. When Russia attacked Ukraine, there was no surge in the price of Bitcoin:

…But there WAS a surge in the price of gold. People still regard gold as a safe haven against geopolitical instability, but they do not yet regard Bitcoin as a safe haven.

One possible reason is Bitcoin’s dependence on the global internet. Yes, you don’t technically need the internet to trade Bitcoin, but as the “bit” in the name implies, it makes it much much easier. If the global financial system carves itself into militarized blocs, the wide-open internet that allows Bitcoin to be easily traded across international borders will likely be far more restricted. Global war might even make the internet go down across much of the world.

But even with the internet up, Bitcoin is incredibly hard to use for transactions. Transaction fees are pretty high even for the small transactions currently being done. But the Bitcoin network simply can’t handle transactions of the size and frequency needed to support the global financial system (this scalability problem is so well-known that it has its own Wikipedia page). Bitcoiners have promised to create a network called Lightning that will solve these problems, but this has proven very difficult to create so far.

There’s also the fact that national governments do have a significant amount of control over Bitcoin. The FBI showed that Bitcoin transactions are traceable, meaning that governments can punish people for making such transactions if they want to. And as China has demonstrated, it’s possible for countries to ban Bitcoin mining pretty effectively.

It’s possible that blockchain technology advances to the point where it’s both immune to national control and able to handle huge and frequent transactions cheaply. So far, it’s not there, and Bitcoin seems unlikely to be the cryptocurrency that gets there first, if any ever does.

So, no Bitcoin standard to replace the dollar-euro.

A little bit of de-dollarization would be a good thing

In this post I’ve argued that dollar-euro financial hegemony won’t be replaced as a result of these sanctions, simply because none of the alternatives is ready to replace it. But it is possible that sanctions might cause a modest shift in the composition of reserve assets held by central banks around the world. Maybe countries won’t shift to yuan-based or gold-based systems, but they might hold a bit more yuan and gold, just as a hedge.

In fact, this would be a good thing.

The fact that countries hold lots of dollar reserves means that there is a large international demand for dollars beyond simply the need to buy U.S.-made goods. Countries like China and Japan and Saudi Arabia park their money in U.S. assets for a number of reasons. One is to insure themselves against a big drop in their currencies — if their currency falls suddenly, they can sell dollar reserves to prop it up. Another reason is because America is a huge and open consumer economy, and countries can sell Americans lots of export goods by keeping their currencies cheap against the dollar — this requires accumulating dollar reserves.

This creates some benefits for America — the so-called “exorbitant privilege”. Holding dollar assets means lending money to American borrowers, so the fact that countries want to hold a bunch of dollar assets means that Americans get to borrow cheaply. This could include American companies looking to borrow money in order to do stock buybacks (or invest in business expansion), American consumers looking to get cheap mortgage loans, or American banks looking to borrow cheaply in order to make more loans.

Great, right? Except this also makes American exports much more expensive overseas, because higher demand for dollars makes the dollar more expensive. This “strong dollar” is one reason for the U.S.’ large and persistent trade deficit:

This pushes the U.S. away from export industries like manufacturing, and toward industries that benefit from cheap borrowing — finance, real estate, etc. In other words, the strong dollar is probably one culprit in the financialization of the U.S. economy.

Over-reliance on dollar reserves also creates risks for other countries. If the U.S. has much higher inflation than the rest of the world (as has happened in the last year or so), this will erode the value of central banks’ reserves (since most of the dollar reserves are bonds with fixed nominal interest rates, whose value inflation destroys). Also, as I argued in Bloomberg, a period of severe political instability in America could cause global financial chaos.

Thus, a modest shift away from the dollar as the global reserve currency would be a good thing — it would help reduce global imbalances, as well as the imbalances within the U.S. economy itself. And it would make the global financial system more robust.

Perhaps now that Europe is looking more vigorous and united as a response to Russian aggression, the euro can become more important as a second global reserve currency. But really, China needs to step it up here. They’re now a very significant portion of the world economy, and yet because of their capital controls they’re not doing their part to support the stability of the global financial system. A moderate international diversification from dollars into yuan would be a good thing, even if — for the reasons stated above — I think it’s pretty unlikely to happen anytime soon.

So to sum up, don’t worry that sanctions will spell the end of the dollar’s role in global finance. This is highly unlikely to happen. And if somehow there is a modest shift away from the dollar, especially toward the yuan, it could help correct some of the system’s current flaws — to the benefit of basically everyone involved.

Exorbitant privilege, or exorbitant burden? If you haven't read them yet, I recommend Michael Pettis and Matt Klein, especially their joint book _Trade Wars are Class Wars_.

They make a nice case that America's soaking up foreign capital actually amounts to not a privilege but a burden, harming American equality and growth.

Roughly -- any dumb errors here are mine, not theirs -- Germany, China and some other countries have rigged their economies so that less income goes to consumers, and more stays with corporations or the government. The result is higher national savings, not because "Germans are thrifty," but because specific policies changed to keep working Germans or Chinese from taking home as much of their GDP contribution as personal income.

These pro-national-savings policies help these countries have competitive exports and robust employment. But it also sticks them with lower consumption and a trade surplus. Where does that surplus end up?

That surplus has to match with a trade deficit. And when countries as big as Germany and China run big surpluses, the final trade deficit is going to land on some country that's big, stable, and open to selling government bonds in trade for cheap imports. In other words: the United States.

In the long run, Pettis and Klein argue, these policies end up basically pushing down the bargaining power of workers worldwide, while, by making American wages less competitive, it quietly inhibits what kinds of jobs are worth companies creating in the United States. It's a small-scale version of a "resource curse," where the American resource worsening our terms of trade is dollars. Dollars, that is, plus our role as the provider of consumer demand to the world. Not because Americans are spendthrift, but because it's the inevitable consequence of our economy being big and open while other countries' economies have been rigged for reduced consumption and surplus exports.

It's a nifty book, and I'd love to read your review of it.

"Using Chinese currency means being vulnerable to Chinese sanctions, and after what just happened to Russia no one will trust China *not* to do that" -- that's a heck of a point.

Ironically, American dollars just became *more* safe than Chinese yuan, because we now all know that your currency of choice is also your sanctions vulnerability.

I suppose crypto really can't be a reserve now unless/until there's a more genuine anonymity. Which should be a technically solvable problem, but will regulators let you trade into an anonymous currency?

Now that currency and bank accounts are sort of weapons, maybe nobody important will be allowed to accept currency anonymity again.

"We don't take cash here! What do you think we are, criminals?"