Does the notion of a "Global South" still make any sense?

There are really four Global Souths.

The Israel-Gaza war has caused a lot of heated rhetoric to be thrown around. One of the big talking points is that the U.S.’ support of Israel will cause it to lose support among the nations of the “Global South”. I don’t know if that’s true or not — Muslim countries seem likely to be at least annoyed with the U.S., but India seems more on the pro-Israel side. But regardless, this has drawn my attention to the highly questionable way in which the categories “Global North” and “Global South” are used — not just in online discussions, but by official organizations like the United Nations.

A lot of people use “Global South” interchangeably with “developing countries”, since countries in the north of the globe tend to generally be richer than countries in the south. In fact, I used it myself, in a post about global development, back in 2021:

But as soon as you try to actually categorize all the countries of the world into two groups, you run into difficulties. For example, in 1980 the Brandt Report, issued by an independent international commission, drew a nice clean line:

The red and blue map at the top of this post, which is from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), is clearly based on the Brandt Line, with just two changes: It moves South Korea and Israel into the “developed” category.

South Korea and Israel…but not Singapore??? Singapore, which UNCTAD still classifies as a “developing” country, is among the very richest countries on the planet. It’s far richer than the U.S., Canada, Australia, Switzerland, or the countries of North Europe:

Nor does this wealth come from oil money, like Qatar or the UAE. Singapore’s economy is a highly diversified high-tech economy. It has the highest number of industrial robots per capita of any country except South Korea. It has the #1 ranking in the World Bank’s Human Capital Index. Its Human Development Index is higher than almost any country’s on the planet — considerably higher than the UN’s own “very high human development” benchmark:

In other words, if Singapore isn’t a developed country, then the term “developed country” is utterly and completely meaningless.

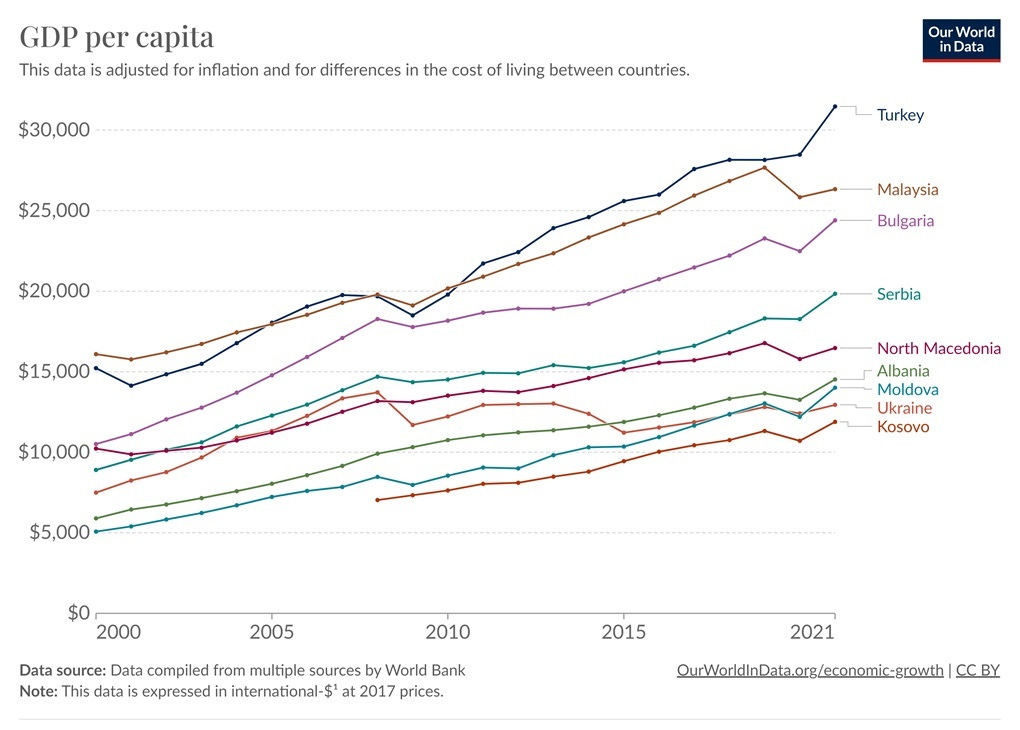

But while Singapore is the most glaring omission here, it’s not the only one. Turkey and Malaysia have grown robustly in recent decades, such that their per capita GDP is now comfortably ahead of a number of the countries that UNCTAD includes in its “developed” roster:

(The gap is narrower if you use the Human Development Index, but it’s still there.)

So what’s going on here? UNCTAD’s website basically says that their present categorization is based on the categories that people used in the past:

This categorization is based on a distinction between developing and developed regions that was commonly used in the past (see Hoffmeister, 2020) and is maintained by UNSD with the understanding that being part of either developed or developing region is through sovereign decision of a state (see the M49 website).

But that makes no sense. The whole idea of a “developing” country is that it’s developing, which means at some point it can become developed. So freezing in the categories of the past makes no sense. Anyway, Hoffmeister’s 2020 paper doesn’t provide much enlightenment here, making some hand-wavey justifications based on which countries have colonial pasts and which don’t (though again, South Korea breaks this mold, and Thailand and Iran never colonized, etc.). It’s only once we go to the UN’s “M49” website that we find some plausible answers:

There is no definition of developing and developed countries (or areas) within the UN system. However, in 1996 the distinction between “Developed regions” and “Developing regions” was introduced to the Standard country or area codes for statistical use (known as M49). These groupings were intended solely for statistical convenience at the time and did not express a judgement about any country’ or area’s stage of development. Over time the use of the distinction between "Developed regions" and "Developing regions", including in the flagship publications of the United Nations, has diminished. Since 2017, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) report and the statistical annex to the Secretary General’s annual report on SDGs progress uses only geographic regions without referring to the two groupings of developed and developing regions. Therefore, following consultation with other international and supranational organizations active in official statistics, the “Developed regions” and “Developing regions” were removed from the "Other groupings" of the M49 in December 2021.

Following its removal from M49, several users expressed the need to maintain the distinction of developed and developing regions based on the understanding that being part of either developed or developing region is through sovereign decision of a state. Therefore, a file was created that contains an updated classification of developed and developing regions as of May 2022, in addition to the historical classification of December 2021…The updated classification reflects a recent action by the Republic of Korea to be considered part of developed regions. (emphasis mine)

So now I think we have an answer. The UN didn’t actually want to draw a distinction between developing and developed countries, and they’ve tried to remove the classification entirely. But certain countries keep insisting that the distinction be maintained. And whether a country gets included in the “developed” or “developing” blocs is basically at the request of that country’s government. South Korea wants the UN to call it a “developed” country, while Singapore, for all its fabulous wealth and high technology, wishes to be called a “developing” country.

One presumes these desires are political in nature. Singapore, a tiny city-state, has to maintain good relationships with the poorer countries of Southeast Asia that surround it, and so would rather not be singled out from them. Turkey and Malaysia probably have similar imperatives. But South Korea would prefer to advertise its successful development on the world stage.

Anyway, this whole investigation might seem excessively punctilious, but the key point is that the notion of the Global South and Global North is inherently a geopolitical one. Much of it has to do with the politics of decolonization, which played out well before I was born. The notion of former European colonies as a geopolitical bloc — embodied by the Non-Aligned Movement, “Third Worldism”, etc. — left its mark on a lot of these economic categories.

But I think it is possible to classify the world’s economies in a more useful way. The World Bank’s four-tier classification system works pretty well, I think:

Income, meanwhile, is closely correlated with other indicators of development like education and health.

But categorizing countries by their income today doesn’t tell the whole story here, because it doesn’t show the picture over time. For instance, if you look at the five major World Bank regions that comprise the “Global South” — East Asia and thePacific, Latin America and the Caribbean, the Middle East and North Africa, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa — you’ll see that they have four very different trajectories:

East Asia — which includes Southeast Asia — is on a strongly upward trajectory; almost all of the countries in this region have either grown rapidly in recent years or are already high-income.

The Middle East and Latin America look basically identical on this graph — they’re both comfortably upper-middle income regions, but they’ve grown more slowly and have stagnated in recent years (though the Middle East has more heterogeneity than Latin America, and obviously has very different governance).

South Asia is still poor, but is making solid gains, and looks like it might be on an upward path like East Asia (though it’s too early to tell). And Sub-Saharan Africa is mostly poor and stagnant, with a few exceptions at the southern tip and the west coast.

It’s not hard to tell what separates the fast-growing countries from the stagnant ones — it’s manufacturing. If you look at which goods these countries export — which is a good proxy for what they specialize in — you’ll see that the fast-growing countries almost all export manufactured goods, while the stagnant ones mostly export natural resources like fossil fuels, minerals, and agricultural products. Economic research shows this correlation clearly.

And economic theory gives us a clear reason why manufacturing-based economies should grow faster than resource-based ones: productivity. There’s lots of scope to improve the productivity of manufacturing, especially if you’re not near the frontier yet. But there’s just not much scope to improve the productivity of resource extraction (especially because the extraction is often done by foreign companies whose technology is already cutting-edge).

Resource exporters can do lots of things to improve their GDP — stable governance, a good business climate for local services, etc. — but ultimately their space for growth is more limited. And even the most well-governed resource-based economies will be limited by their population sizes — if your country has hundreds of millions of people like Nigeria does, resource rents will be stretched thin, while if you have only a few million people like Norway, there will be more to go around.

In other words, there are basically four Global Souths. I think I’ll give them names:

The mostly-developed countries: Industrialized countries that are on the cusp of developed status, and are only thought of as “developing” for historical or political reasons. These include Turkey, Malaysia, and arguably China, Thailand and Mexico.

The industrializing countries: Rapidly industrializing countries that are still poor or middle-income but are growing fast. There include India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, the Dominican Republic, and potentially the Philippines and Indonesia.

The resource exporters: Upper-middle-income countries that specialize in resource extraction. These include Brazil, Colombia, South Africa, Iran, Botswana, Namibia, Kazakhstan, and so on.

The poor countries: These countries mostly export natural resources but either don’t have enough of them to afford decent standards of living, or are plagued by war and/or poor governance. These include countries like Nigeria, Ethiopia, Afghanistan, Somalia, Pakistan, Sudan, and so on.

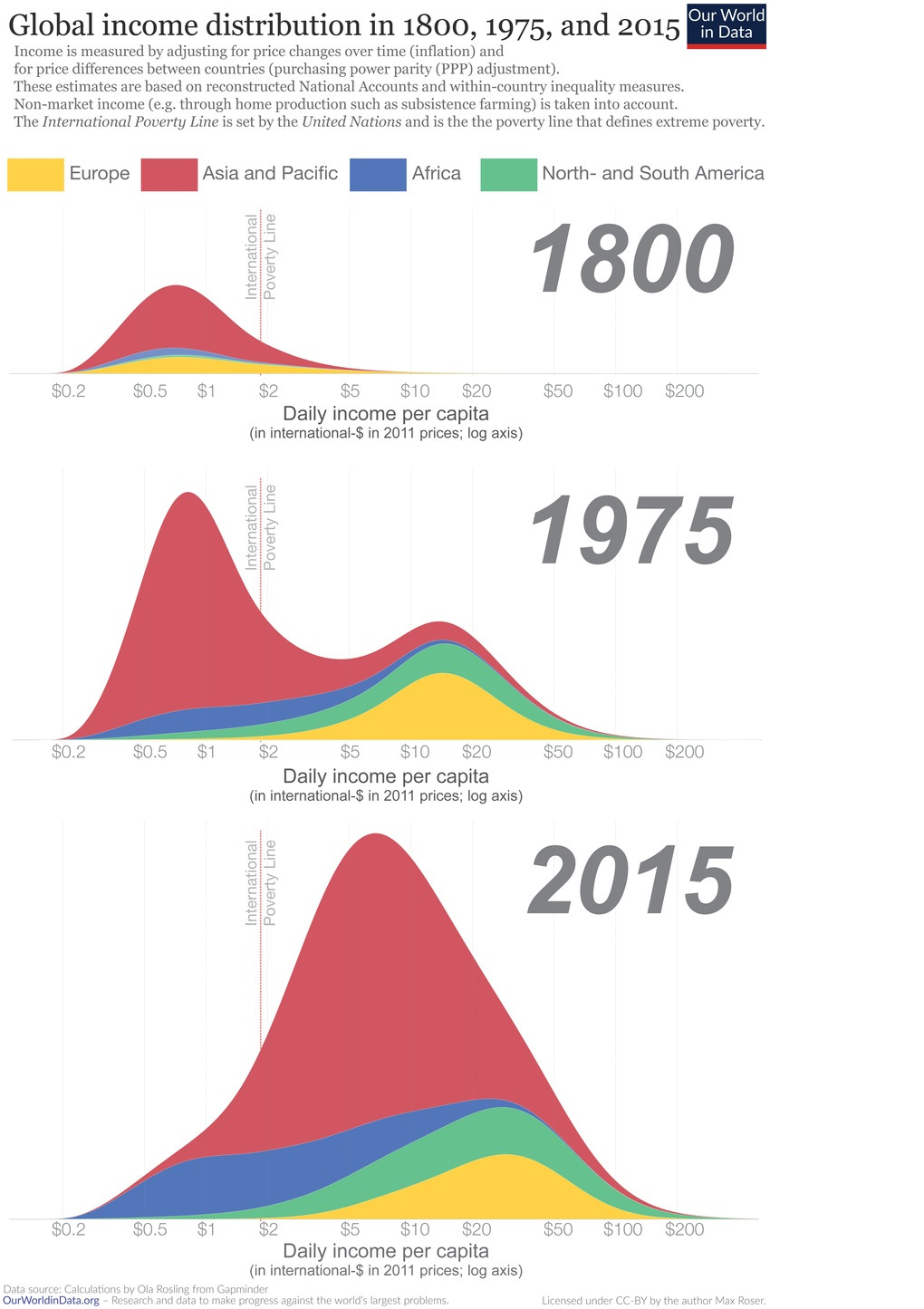

Every time a country moves from the “industrializing” category to the “mostly-developed” category, the old dividing lines between Global South and Global North become a bit less relevant. Already, this process has turned the two-peaked global income distribution of the old colonialist world into something that looks much more natural:

Continuing this process should be the goal of development policy — for poor countries, but also for rich countries and international economic organizations that have an interest in a richer, more equal world. This means helping the industrializing countries escape whatever “middle-income traps” they find themselves in, and propelling as many of the poor countries as possible onto the escalator of industrialization. Industrialization is the means by which the shackles of the colonial age are thrown off; by this means we can build a world where nations respect each other as equals.

I fear that many on the political Left don’t understand this. When I read accounts of global economic development by thinkers who lean to the socialist side, I often encounter nostalgia for the “trente glorieuses” — the three postwar decades. In those decades, most of the industrial growth happened in rich countries — the old “Global North” — and poor countries mostly exported resources to them. To people on the left, this relationship represents at least a partial rectification of the exploitation of colonialism — finally, the Global South was getting a fair price for their resources!

And sure, it was an improvement. But fundamentally, it still represented an unequal relationship — the Global North controlled all the high-value-added and high-tech parts of the supply chain, while the Global South mainly dug up rocks for them. Ultimately, that pattern of development was a trap for the resource exporters of the Global South, because it meant they could only rise as high as their resource endowments would allow them to. The stagnation of countries like Brazil and South Africa demonstrates that there’s an inherent ceiling to resource-based development. (Many saw this trap and tried to break out of it, but only a few like South Korea and Taiwan succeeded.)

The decades since 1990, however, have been a much different story. Manufacturing has finally spread beyond the boundaries of the Global North. It’s not just a few countries like Turkey and Malaysia joining the party, either — China now manufactures more than the U.S. and Europe combined, and the countries of South and Southeast Asia are rising fast.

I believe that despite the geopolitical disruptions caused by the industrialization of much of the Global South, ultimately this will lead to a world that’s both richer and more equal. And we’ll know it’s working because the categories of Global North and Global South will start to make less and less sense; the more ridiculous and out-of-date the old Brandt Line starts to look, the brighter the future will be.

I would add a category called “failed states” where the little development that these managed to have is going in reverse. Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Lebanon, Syria and the likes.

I get the impression that the countries who are keenest on the term “Global South”, or the rhetoric related to it, are middle-income regional hegemons. For countries like China, Turkey, and Brazil, the term itself and some other Global South-flavoured language (E.g. developing country, post-colonial) are handy to make them seem less threatening to their neighbours. Even Russia is keen on the notion that the “Global South” is on its side. Singapore is not a regional hegemon, but it uses the term to fit in more, as you pointed out.

India is interesting. The government seems to use the idea selectively when it benefits it, like in climate negotiations. But it is way less eager than some others to couch its entire geopolitical strategy in that terminology.