Did macroeconomics fail us on inflation?

No. But maybe we failed it.

When the financial crisis of 2008 descended upon the world, Queen Elizabeth famously asked why no one saw it coming. Over the next several years, an extraordinary amount of intellectual effort (and quite a bit of acrimony) went into debating the answer to that question. Some, like Paul Krugman, criticized the academic discipline of macroeconomics for ignoring the importance of the financial sector and the zero lower bound on interest rates, and for building models that were mathematically beautiful but practically useless in a crisis. (As a grad student blogger, I joined in that chorus, arguing that macroeconomists should pay more attention to microeconomic data, and lamenting the persistence of outdated models.)

The critics made many good points, but we were a little too harsh. A few macroeconomic papers did take the danger of a financial crash into account, and some of these luckily happened to have been written by the economist who was chair of the Federal Reserve at the time. Macroeconomists had made many silly models, but the central bankers who made monetary policy used a pragmatic, eclectic approach that led them to engage in an aggressive program of quantitative easing. Keynesian economists successfully convinced President Obama to enact a bold stimulus plan. And academic macro proved itself to be far from an ossified discipline, quickly adding in the things it had left out before.

Now, the U.S. is confronting another unexpected macroeconomic shock. Although the economy is doing great in terms of jobs and growth, it’s plagued by worryingly high inflation, which accelerated to new highs in December. That’s eroding real wages for middle-class workers, causing political headaches for the Biden administration, and possibly even threatening to morph into a devastating inflationary spiral.

So it’s natural to ask the question: Did macroeconomics get it wrong again? Were macroeconomists so focused on fighting the last war — modeling the financial sector and thinking about depressions — that they missed the big inflation?

Well, no, not really. Basic macro still works to give us a general sense of what’s going wrong (and right) in the economy right now. But with the help of new data, macroeconomists might be able to help us understand a lot more about inflation than we did in the ‘70s and ‘80s.

Basic macro explains the inflation situation pretty well

Basic macroeconomics is Keynesian macroeconomics. It revolves around the concept of some kind of tradeoff between growth and price stability (sometimes called a Philips Curve). The fancy models that central banks use have this concept embedded somewhere deep inside them. But to understand the basics, we can just look at a very simple model — aggregate demand and aggregate supply, or AD-AS.

So there are two basic explanations for the inflation we’re experiencing currently. These are:

1. The supply chain crunch

2. Increased consumer demand from the Covid relief spending and Fed relief actions of 2020 and 2021

In fact, we can use the simple little AD-AS model to evaluate these two competing hypotheses!

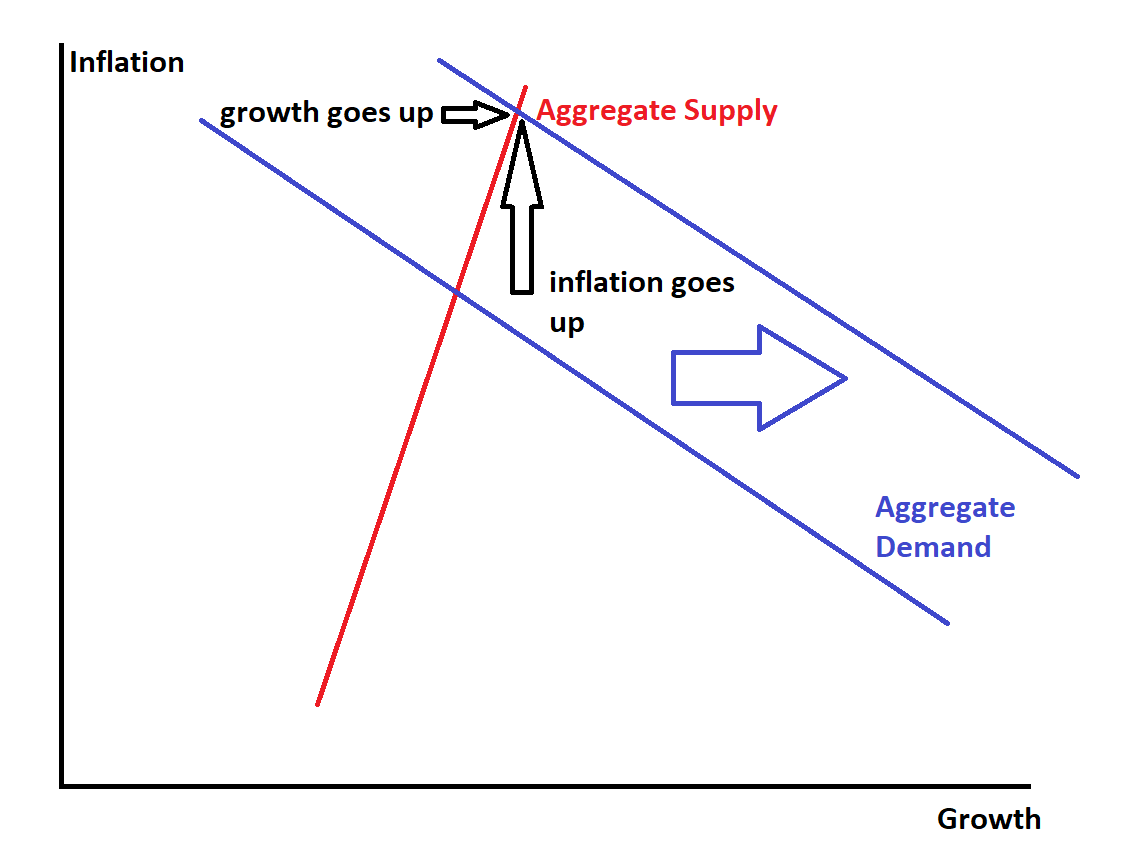

So, suppose that there’s been a negative shock to aggregate supply. In this explanation, Covid has disrupted factories and logistics networks, making it harder for goods to reach consumers. This would be sort of analogous to the oil shocks of the 1970s, except that instead of oil suddenly becoming more costly, it’s computer chips, lumber, etc. In the AD-AS model, that would look like this:

That would give us something like the stagflation of the 70s, with slow growth and high inflation.

On the other hand, maybe Covid relief spending pumped up aggregate demand, leading to a red-hot economy. That would look more like this:

In this situation, we also get inflation, but this time instead of stagnation we get rapid growth — a red-hot, overheated economy, where too much money is chasing too few goods, and prices have to rise.

So where are we now? Is growth slow, indicating a negative supply shock, or is growth fast, indicating a negative demand shock?

Well, in fact it’s hard to say; you can make arguments for both. On one hand, growth was very fast in 2021 — it’s forecast to come in at 5.6% for the year when the numbers are finally tallied. On the other hand, GDP isn’t quite back to its pre-pandemic trend. Unemployment is historically low, but because many people have left the workforce, the prime-age employment-population ratio is still below the level of 2019.

In other words, whether you think the economy is overheating or is being held back by a supply crunch depends mainly on your expectations of how fast the economy could be growing right now — on your guesses about potential output or the natural rate of unemployment. If you think we could be growing even faster than we are right now if those pesky supply chain snarls weren’t holding us back, then that’s a negative supply shock.

Jason Furman, the former CEA Chair (and Noahpinion interviewee) has a recent presentation in which he argues that it’s primarily a demand shock, and that we should have seen it coming a mile away. His basic argument is that if we were seeing a negative supply shock from supply chain problems, we’d see traffic at ports be reduced from where it was in 2019 — just as U.S. oil consumption fell during the oil shocks of the ‘70s. But instead, we’re seeing port traffic above where it was at the peak of the previous boom:

That’s a strong indication that we’re seeing a positive demand shock in the market for imported goods that outweighs any negative supply shock in that sector. And since this is the sector that gets implicated as the cause of the negative aggregate supply shock, the fact that port import volumes have increased also implies that the negative supply shock has been outweighed by a positive aggregate demand shock.

Now, that doesn’t mean supply chain problems had nothing to do with this inflation! But the connection is probably a little more subtle than with oil in the 1970s. Our creaky, over-engineered, inflexible, over-regulated ports and logistics systems (described vividly by Ryan Peterson in our recent interview), combined with the fact that American manufacturing has been hollowed out and didn’t have the ability to ramp up production quickly, made America’s aggregate supply less elastic, which magnified the effect of the demand shock on inflation and held back growth. Here’s what that looks like on the graph:

If America had better manufacturing, better ports, and better logistics, we would have gotten faster growth with less inflation. So we should work on those things.

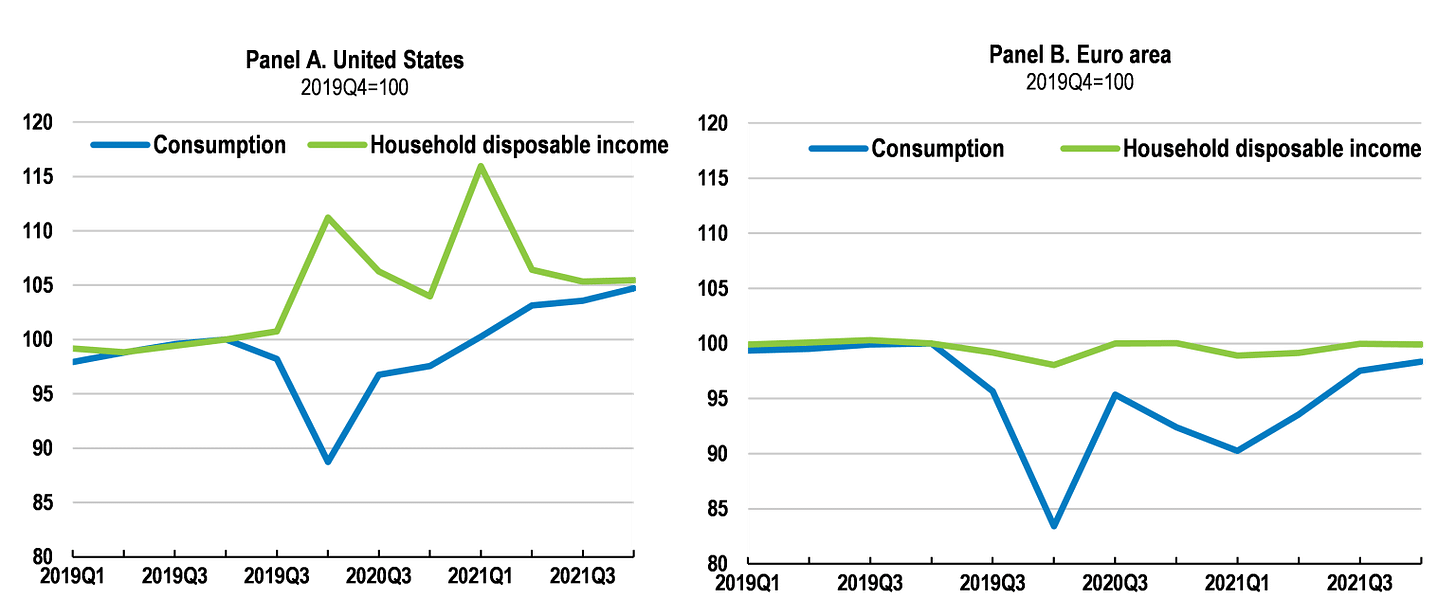

So, the final piece of this story is the positive shock to demand. Comparing America with Europe suggests that our greater Covid relief spending and our bolder central bank policy take a lot of the credit for the boom in growth and employment, but also bears much of the blame for inflation. Laurence Boone, chief economist of the OECD, has a good post in which he lays out this comparison. You should read the full post, but I’ll bring over a couple of her graphs. Boone shows that U.S. household disposable income and consumption both increased much more than in Europe:

And he breaks down consumption to show that the difference mostly consists of greater American spending on physical goods:

Again, this tells a story of increased demand outweighing any decrease in supply; we’re not cutting back like we did in the ‘70s.

Anyway, as you might expect from the simple AD-AS model, increased U.S. spending relative to Europe is matched by higher inflation:

So the most plausible story here is that the U.S. did more than Europe to support the economy, both on the fiscal side and in terms of monetary easing and lending support from the central bank, and that this translated into greater income, greater spending, and — because we had creaky supply chains and insufficient manufacturing capacity — much greater inflation as well.

Thus, a very simple standard undergrad-level macro model — more sophisticated versions of which are used by the Fed and other central banks, and are dominant in the academic macro field — was able to explain the basic story of our current inflation. It tells us that in the short term, inflation was an unavoidable consequence of the things our government did to support our economy and ensure a rapid recovery. And it suggests that in the long term, investments in upgrading our ports and increasing domestic manufacturing capacity would require less of a tradeoff between growth and inflation in any similar situation.

So basic macro does OK! But that still leaves us with many mysteries. Most importantly, it leaves us with the question of how much inflation is too much. At what point do these price increases stop simply being a drag on wages, and become a dire threat to economic output itself? And what must the Fed (and/or Congress) do to prevent things from getting out of control? And what will be the cost of those safeguards? Here, our ignorance outweighs our knowledge, and academic macro needs to give us more answers.

Macro needs to tell us more about inflation

One big problem with the AD-AS model is that while it tells a simple story, it doesn’t actually fit the historical data very well. An AD-AS model should produce a Phillips Curve — a relationship between unemployment and inflation (which is really a relationship between growth and inflation). In fact, the more complex models that yield fancy versions of AD-AS also feature fancy Phillips Curves. But there’s a large literature showing that in practice, the Phillips Curve is pretty flat — in other words, monetary and fiscal policy don’t seem to have much effect on inflation in recent decades. In other words, we did a ton of quantitative easing and fiscal borrowing and spending in the Great Recession, and yet inflation didn’t budge.

I won’t do a whole tedious review of the literature, but my favorite paper showing this result is “The Slope of the Phillips Curve: Evidence from U.S. States”, by Hazell, Herreño, Nakamura & Steinsson (any regular readers of mine will know that Nakamura and Steinsson are probably my two favorite macroeconomists working today). Here’s the abstract of that paper:

We estimate the slope of the Phillips curve in the cross section of U.S. states using newly constructed state-level price indexes for non-tradeable goods back to 1978. Our estimates indicate that the slope of the Phillips curve is small and was small even during the early 1980s. We estimate only a modest decline in the slope of the Phillips curve since the 1980s. We use a multi-region model to infer the slope of the aggregate Phillips curve from our regional estimates. Applying our estimates to recent unemployment dynamics yields essentially no missing disinflation or missing reinflation over the past few business cycles. Our results imply that the sharp drop in core inflation in the early 1980s was mostly due to shifting expectations about long-run monetary policy as opposed to a steep Phillips curve, and the greater stability of inflation since the 1990s is mostly due to long-run inflationary expectations becoming more firmly anchored.

So to really predict inflation, we’re going to need a lot more than a simple AD-AS model. In fact, when we look at how price changes for various goods and services are correlated, it sure seems as if there’s one unifying thing driving inflation. But if it’s not simply aggregate demand, what is it? Hazell et al. think that the missing piece is expectations. Basically, if the public starts to believe that the Fed isn’t going to be very tough on inflation, then businesses will raise prices, and inflation will become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

But not everyone agrees! The Fed’s Jeremy Rudd has a recent paper in which he argues (with a scornful fire befitting the blog wars of the early 2010s!) that there’s no good evidence that inflation is driven by inflation expectations at all. His arguments basically boil down to two things — the highly implausible nature of the assumptions in modern macroeconomic models, and the difficulty of doing empirical measurement in macroeconomics without relying heavily on assumptions.

Both of those are very good points (and are both points that I sketched out back during the blog wars of the early 2010s). But rather than retreat into nihilism, macroeconomists should simply look at more data and make better theories. After all, we have vastly more microeconomic data today than we did in the 70s and 80s, when the contours of our theories about inflation took shape. And in fact, we have vastly more data today than we did even in the 1990s, when economists did a bunch of research on the way companies determine their prices.

In fact, a number of macroeconomists are currently tackling this question, using tools such as surveys to gauge the inflation expectations of businesses and households, and relate these to actual price-setting and consumption behavior. For example, D’Acunto et al. (2019) look at very detailed data on consumer purchases and find that consumers’ inflation expectations are driven by the prices of the things they buy from day to day (not very surprising). And Candia et al. (2021), Coibion et al. (2018) and other papers find that if surveys are to be believed, neither households nor corporate managers pay very much attention to inflation or monetary policy!

That seems consistent with Rudd’s dismissal of the role of expectations, but there are other papers that contradict his fiery assertions. For example, Cloyne et al. (2016) combine very detailed pricing data with surveys of businesses in the UK, and find that businesses’ inflation expectations plays a very large role in how they set their prices!

We need more studies like this, in order to nail down the relationship between expectations and prices. And crucially, we need them in countries where there have been big changes in inflation and/or big changes in monetary policy, so we can evaluate the sort of regime shifts in expectations that Hazell et al. use to explain U.S. inflation in the ‘70s. And if expectations turn out not to be the missing factor, we need to find out what it is.

Most importantly, we need much more research on what causes hyperinflation — the sort of catastrophic, spiraling inflation that lays waste to whole economies and societies. As I noted in a post almost exactly one year ago, macroeconomists have done precious little research on this topic in recent decades; most of what we have comes from the ‘70s and ‘80s. This is a true case of macroeconomists fighting the last war — as soon as the U.S. seemed to have inflation under control, the very U.S.-centric macro profession took less of an interest in the phenomenon. Among the few I found were:

1. A 2021 theoretical paper by Obstfeld & Rogoff shows that in a broad class of simple models, the only way a hyperinflation happens is if there’s “a large-scale government resort to monetary finance of deficits” — in other words, if the Fed starts printing money to fund Congress’ borrowing directly.

2. A 2018 paper by Lopez & Mitchener argues that policy uncertainty was key to the hyperinflations in several Central European countries after World War 1.

3. A 2018 paper by Saboin looks at many hyperinflations in various developing countries, and finds some empirical regularities — for example, inflation seems to persist at a high but not hyper- level for between 2 and 12 years before the devastating spiral really kicks off.

4. A 2006 paper by Sargent, Williams & Zha tries to model South American hyperinflations as a function of money-financed government borrowing (i.e. the same thing that causes hyperinflations in Obstfeld & Rogoff’s theory above), and finds that this model fits the data reasonably well.

So that’s somewhat helpful. But this handful of papers — none of which should be taken as definitive or conclusive — is not nearly enough. Hyperinflation is one of the most devastating economic phenomena in existence, and whether and when it could happen to America is absolutely critical in answering the question of whether it’s worth it for the Fed to act now to push inflation back down to 2%, even at the risk of recession.

In fact, we will not be able to answer that question definitively in time; we will have to act on our best instinct, and on hints cobbled together from real-time data and the theories of the ‘70s and ‘80s, and hope for the best. But hopefully this brush with inflation will reinvigorate macroeconomists’ interest in the topic in the decades to come. And hopefully the next time a developed country finds itself suddenly experiencing rapid inflation, it’ll be able to rely on something better than simple textbook models.

Occam’s Razor would suggest that handing out checks to people is a pretty good way to create inflation

I think the discussion of what’s happening to AD needs a closer look than just “what’s the current stance of fiscal and monetary policy? Loose? AD must be rising then”. A key component of AD is private sector borrowing from banks.

Sometimes (2008) you have an impaired banking system that won’t lend, and households/businesses (frightened by recession and with weak balance sheets) that won’t borrow… you can cut interest rates to zero and do a bucket load of QE, net bank lending will remain negative and the impact of these monetary policy moves on AD will be limited. That leaves fiscal policy / government spending as the only game in town. The 2008 fiscal stimulus was insufficient and the economy stagnated.

In other circumstances (2021?), household balance sheets are strong and corporate profitability is high because of muscular gov bailouts early on. Loose monetary policy spurs demand for housing and mortgage lending accelerates - this results in a more rapid increase in the money supply and then rising spending across the economy. Eventually we hit supply constraints, and inflation rises.