Did immigration bring down inflation?

I'm highly skeptical of this theory, but it's still quite interesting.

Just a quick little econ post for your Sunday enjoyment.

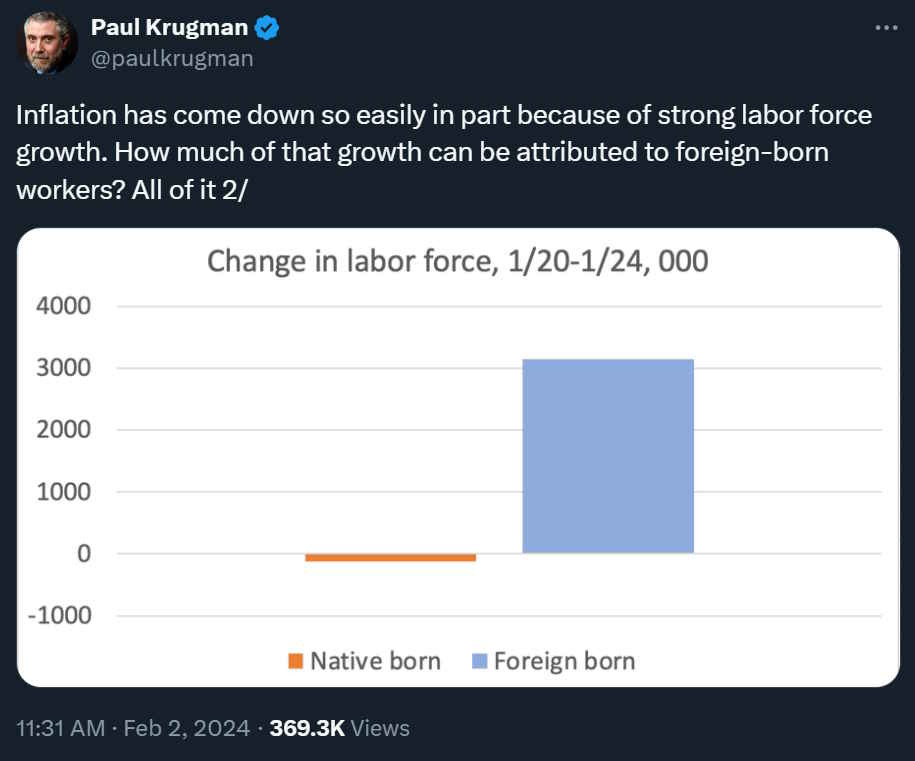

Paul Krugman has an interesting hypothesis about why inflation has come down since mid-2022. He believes a big part of it is due to increased immigration:

The more I think about this argument, the weirder and more interesting it becomes.

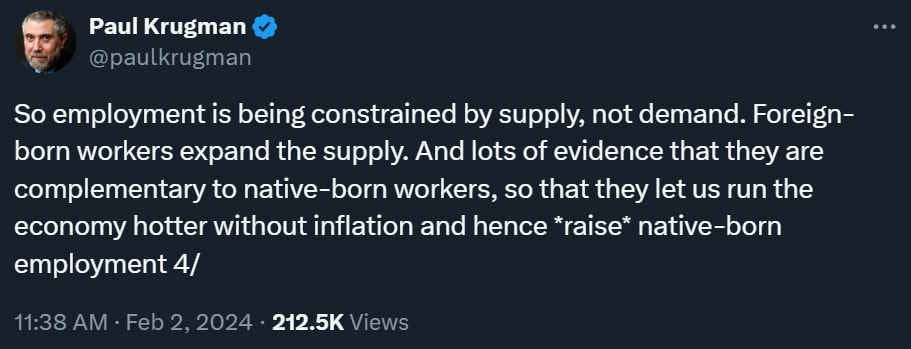

Basically, Krugman is arguing that immigration is a positive supply shock:

This is kind of a weird way to frame it — if we expand aggregate demand to keep pace with a supply shock, growth gets a big boost, but inflation remains roughly the same, rather than falling. So that was a bit confusing.

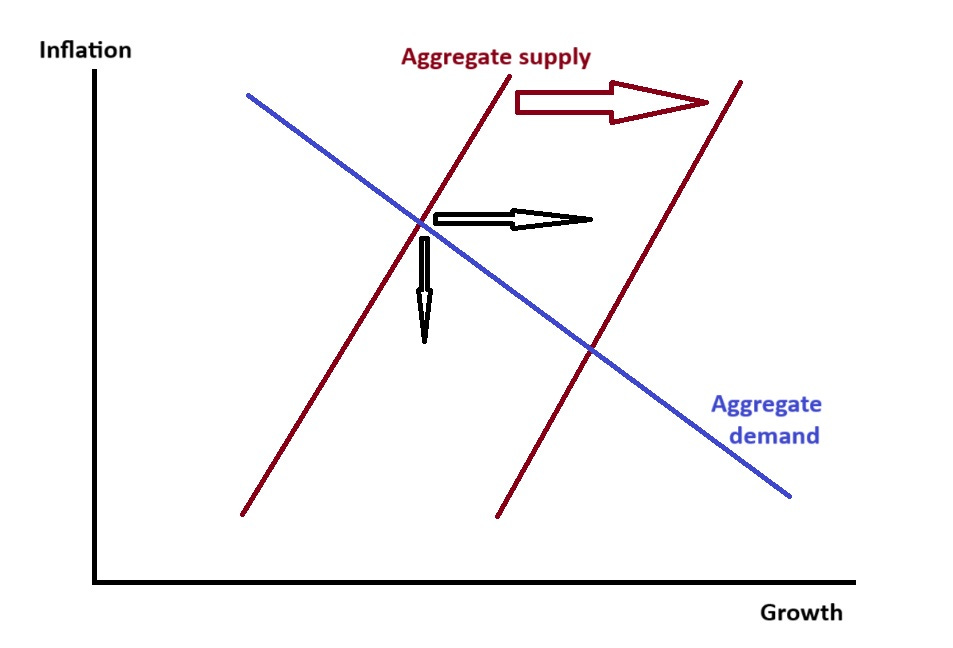

But anyway, what I really think Krugman is saying here is just that immigration represents a positive aggregate supply shock. Remember that when aggregate supply shifts in the positive direction, growth rises and inflation falls:

OK, but why would immigration increase aggregate supply? Basically, aggregate supply goes up when companies’ costs go down. So Krugman is saying that immigration pushed down costs for U.S. companies.

“But wait!”, you may be saying at this point. “Noah, didn’t you tell me that immigration doesn’t reduce wages?”

And yes, that was the title of a post I wrote:

BUT, that was actually shorthand. What I meant was that immigration doesn’t reduce wages for the native-born. Usually, when we have debates about immigration and wages, we’re talking about wages for native-born Americans. And as I explain in that post, the evidence strongly suggests that the increased demand for native-born labor that immigration creates roughly cancels out the increased supply of labor in occupations that native-born Americans do. And that leaves wages and employment unchanged — for the native-born.

But when we’re talking about immigration’s effects on companies’ costs, we need to think about how immigration affects the wages of other immigrants who are already in the country. And here, the evidence shows that the supply effect outweighs the demand effect — immigrants do tend to compete down each other’s wages.

Why the difference? Because immigrants and native-born people tend to do different kinds of jobs. So immigrants mostly compete with other immigrants in the labor market, not with the native-born.

So Krugman is arguing that the surge of immigration under Biden has pushed down the wages of immigrants, lowering costs for companies and thus expanding aggregate supply. His evidence is that since the pandemic, the wages of immigrants have fallen relative to the wages of native-born Americans:

This graph doesn’t really do much to convince me of Krugman’s case. First of all, the timing is suspect. The big drop in immigrants’ relative wages came from 2021 to 2022, just as inflation was at its highest. That doesn’t fit the story of falling immigrant wages letting companies reduce costs. By the time inflation started falling, immigrants’ relative wage decline was petering out.

Second, this is just a graph of relative wages between immigrants and the native-born, not overall wages. Overall wages are what matter for costs. And overall real wages in America fell during the period of high inflation in 2021-22, and then rose during the period of lower inflation in 2023. So corporate labor costs were falling when prices were rising rapidly, and rising when prices were rising slowly. That definitely doesn’t fit Krugman’s story.

Now, you could tell a more complicated form of this story, where the wage changes and the inflation changes don’t have to line up with each other — you could bring in expectations, various sorts of inertia and lags in the system, etc. But the simple story doesn’t seem to fit the timing of events.

But OK, let’s think about a more complicated story here. One thing we do know about wages is that while wages for production and nonsupervisory workers have returned to their long-term trend, wages for managerial workers haven’t caught back up, and the gap was still growing as of 2023:

So can we tell a story where immigration is depressing wages for managers, but not wages for regular workers? Perhaps we can. Observe this breakdown of the increase in immigration from 2022:

The light blue bars at the top include asylum seekers — the people you hear about flooding across the border. But even though that number has increased, it’s still a lot smaller than the amount of immigration that’s due to people coming in on visas — student visas, work visas, and so on.

Immigrants who come with visas tend to be highly skilled and educated, and this has become even more true in recent decades. Meanwhile, it seems likely that we're not missing a huge wave of low-skilled immigrants who sneak across the border and evade the Border Patrol and disappear into American cities, as was common in the 90s. Instead, nowadays the poor immigrants are sneaking across the border and turning themselves in to the Border Patrol in order to ask for asylum. So we have a record that they came. And thus they are probably mostly being counted in that light blue bar in the graph. Which means that most immigration to the U.S. is of the educated and/or skilled variety.

So maybe immigrant managers are depressing the wages of other immigrant managers. And maybe this is creating a bonanza for companies, who get to hire immigrant managers more cheaply, and who then pass the cost savings on to the customer in the form of lower inflation.

And to round out this version of the story, maybe managers — and especially immigrant managers — do important tasks that basically no one else can or will do. Maybe immigrant managers are a key bottleneck in the production system, because they’re more skilled, or have stronger work ethic, or simply that they’ll do jobs that the native-born would turn up their noses at. So maybe the wages of immigrant managers are important out of proportion to their direct contribution to the national average.

It’s possible to imagine a story like that. It’s a very interesting story, because it’s not at all about low-skilled asylum seekers pushing down aggregate wages. Instead it’s about managers — and in particular, the kind of managerial jobs that only immigrants can or will do. Basically, it says that if the U.S. wants our economy to grow faster, we need to flood the market with skilled immigrants in managerial roles. That would be a very important lesson. One good general rule of thumb is to never underestimate the importance of high-skilled immigration.

But anyway, we should also consider the possibility is that Krugman is just plain wrong, and that immigration played little role in America’s successful disinflation in 2023. After all, even with increased immigration, U.S. population only increased by 0.5% in — a lot more slowly than in the years before the pandemic. If that’s a supply shock, it’s a pretty anemic one. So I think we should consider the possibility that inflation fell because of a combination of the Fed’s decisive action and the fading of pandemic-era supply shocks.

None of this means immigration is bad, of course — it grows the tax base, it anchors industrial clusters, relieves production bottlenecks, transfers know-how, and so on. Immigration is good — it strengthens our country immeasurably. But that doesn’t mean we should give it credit for everything good that happens in the economy.

The problem with Krugman is that he's extremely partisan. He's basically starting with a premise of defending Biden, and then working backwards to see all plausible arguments that might lead there. No amount of 'predictions' that prove him wrong in hindight seems to reduce his fan following in the New York Times

It would be interesting to do this analysis in Canada, where immigration growth has been considerable relative to country size.