Defending the status quo is not environmentalism

In the 21st century, building things is the key to protecting nature.

American environmentalism started out as conservationism. The U.S. possessed a vast unspoiled landmass, and the industrial age was just getting started. Protecting natural habitats and natural beauty meant slowing down the construction of basic industrial infrastructure — railroads, highways, power lines, gas stations, and so on. So a lot of the famous early environmentalists you hear about are conservationists like John Muir, whose goal was to establish zones where nature was protected from industrial encroachment.

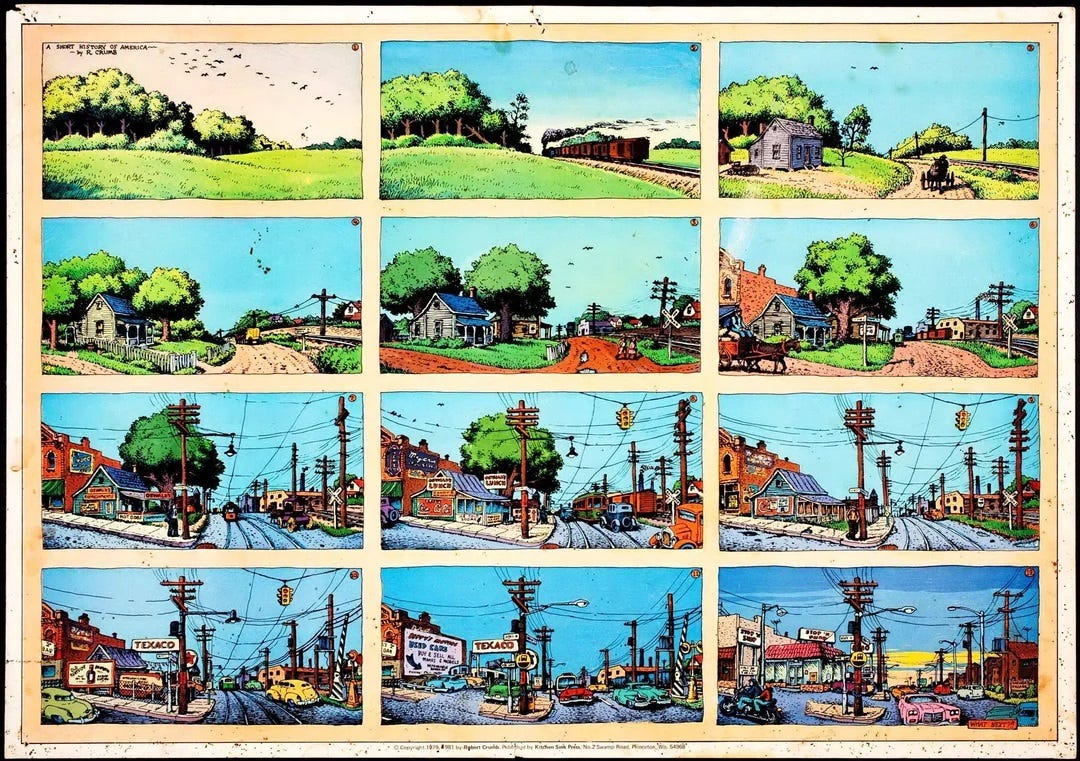

You can see the tragic story of development destroying natural beauty everywhere in America. Two of my favorite examples are John Prine’s song “Paradise”, and this cartoon by R. Crumb, entitled “A Short History of America”:

Creating natural parks and other development-free zones was a good idea. But the conservationist effort deeply and permanently colored Americans’ thoughts about environmentalism in ways that are not always helpful to address the modern-day environmental challenges that we face.

Today, our biggest environmental challenges require us to build new things. Climate change requires that we build vast fields of solar panels, and the infrastructure to transmit solar power to the grid. Habitat destruction requires us to build dense cities full of high-quality infrastructure and multifamily housing, so that humans can have somewhere pleasant to live without gobbling up the wilderness.

But some factions of the modern environmental movement are stuck in the anti-development frame of mind. Back in January, Jerusalem Demsas wrote an excellent article about this problem in the context of Minneapolis’ housing policies:

[I]n Minneapolis, the green community has fractured as a wide array of self-described environmentalists find that they don’t agree on very much anymore…Back in 2018, Minneapolis…legalized duplexes and triplexes in all residential neighborhoods. The plan led to a frenzy of ambitious regulatory changes meant to yield denser, transit-accessible, and more affordable homes across the city…[S]upporters also stressed the environmental benefits of funneling population growth toward the urban core instead of outlying counties…

From the beginning, though, many in Minneapolis perceived the plan as an attack on their way of life…a newly formed group called Smart Growth Minneapolis, the local chapter of the National Audubon Society, and another bird-enthusiast group sued under the Minnesota Environmental Rights Act…Hundreds of planned housing units are on hold…

[S]upporters of the plan described a common pattern in which not-in-my-backyard types look for any excuse to block things they dislike. “A lot of people come to us to stop development projects,” Colleen O’Connor Toberman, the land-use director at a Minnesota environmental organization, told me. “I definitely also hear from people who are like, ‘I don’t like this. Please help me find the environmental grounds to oppose it.’”

Many climate writers are livid.

As Demsas writes, this represents a crisis at the very core of the U.S. environmental movement. It’s not a disagreement over tactics, messaging, or leadership; it’s a fundamental disagreement over what it means to protect the environment.

On one side are environmentalists who have a transformative vision of what environmental protection should look like. They envision a pattern and type of human development that exists in greater harmony with nature than what we have today — energy production that doesn’t cook the planet, big cities that don’t sprawl over fields and forests, industries that don’t belch toxic waste into the air and water. To these people, “the environment” means the entire natural world, and the way to protect it is to reshape human development.

On the other side are faux-environmentalists for whom “the environment” means the small pieces of nature that they experience in their day-to-day lives — the blue sky outside their windows, the lush green lawns in their neighborhood, the open space near their houses. And they want to protect that “environment” by freezing the status quo of the physical world around them. That requires preventing the construction of buildings that might block their views or pave over nearby lawns, solar plants that might mar the view on their hiking trails, and so on.

It should come as no surprise to readers of this blog that I side with the former group. Conservation is a great idea when it means protecting unspoiled areas of natural habitat; preserving the prettier parts of the existing suburban sprawl is not something I particularly value. And halting the warming of the planet before it becomes catastrophic is a much more important task than blocking unsightly power lines and solar panels.

Anyway, this conflict is playing out within the progressive movement, the Biden administration, and the nationwide battles over housing and energy construction. The anti-development “environmentalists” haven’t entirely carried the day, but they’ve won far too many battles.