Contemporary China vs. Imperial Japan

Mostly they're nothing like each other.

In discussions of the emerging U.S.-China rivalry and military tensions in East Asia, it’s pretty common to see people draw parallels between the China of the 2020s and the Japanese Empire of the 1930s. The reason is obvious — they’re both in East Asia and they both had bad relations with the U.S. But although there are a few minor, scattered similarities, mostly the two nations are just utterly different.

The differences — economic, cultural, historical, geographical — are too many to enumerate, but I see three big ones that especially matter when thinking about the possibility of a U.S.-China conflict. These are:

governmental structure and institutional distribution of power

size

military culture and experience

One-party state vs. chaotic anocracy

This post was actually inspired by a book I recently read: Richard McGregor’s The Party: The Secret World of China's Communist Rulers. Though it’s almost a decade old at this point, many of its insights about the relationship between the Chinese Communist Party and the other institutions of Chinese society probably still hold.

The key idea that ties the entire book together is that China’s governance is extremely centralized — not in terms of Beijing versus the provinces, but in terms of the distribution of power across institutions. Businesses, courts, the military, local governments, and other social institutions that in other societies might represent alternative sources of ideas and authority are dominated by the CCP. This is done in some cases through formal governmental structures, but usually via informal, backchannel contacts — kind of like a local mafia organization might control local businesses. The CCP is essentially one giant mafia with tentacles in every piece of the country. This creates many advantages and disadvantages, some of which McGregor lays out.

But that sort of governmental structure is utterly different from what prevailed in pre-WW2 Japan. (Two good sources here, if you want to start reading about what Japan was like at this point, are Marius Jansen’s The Making of Modern Japan, and John Toland’s The Rising Sun.) Although Americans might have conceived of Japan as a sort of hive mind controlled from the top down by the Emperor, in fact it was nothing of the sort. The Emperor occasionally wielded power, and certainly commanded respect, but often reigned at an Olympian remove — such a remove, in fact, that in many cases it’s not even clear whether his power was real or notional.

In addition to the Emperor, Japan had a number of semi-autonomous institutions that competed with each other over the boundaries of their often-overlapping spheres of influence. These included the Japanese military, large business conglomerates called zaibatsu, and the country’s official parliamentary government (which was democratically elected for a while, then came under military control). Other groups also mattered — the Genro, a group of elder statesmen who advised the Emperor and meddled in politics, and various rightist ideological factions that ended up launching multiple coup attempts and helping to instigate the conquest of Manchuria.

Japan was thus an anocracy, and a highly confused, chaotic one. How this shambolic confusion of competing organizations and interests managed to take over much of Asia and contend militarily with the world’s leading powers is a fascinating tale that deserves a much longer treatment.

But the upshot here is that in Imperial Japan, no one was really in charge, and that made dealing with Japan incredibly difficult. You could make peace with the Japanese government, and then an independently operating Japanese military force motivated by rightist extremism might just invade you anyway. You could negotiate with one part of the government while another part had already decided to attack you. You could present a list of surrender demands, but to whom? Eventually World War 2 ended only when the Emperor stood up and exerted more than nominal authority, overruled his generals, survived a military coup attempt against him, and made the final decision to surrender.

In contrast, in China, someone is in charge, and his name is Xi Jinping. Not only does the Party rule China, but Xi rules the Party, and most observers seem to agree that he has consolidated personal power to an extent not seen since Mao. He has crushed rivals, rooted out corruption, and extended state control over business and the economy.

That could make China easier to deal with than Imperial Japan was, because in China there’s a real negotiating partner — if they decide to talk to you. With Imperial Japan, there was nothing to do but wait until the more radical elements within the chaotic power structure forced the country to do something crazy, then clean up the mess.

But China’s more centralized party control could also make it a more formidable opponent than Japan. The Japanese Empire’s war effort was hampered by deep inter-service rivalry, rogue military units, and poor coordination at the top. China, in contrast, would probably run like a well-oiled machine, thanks to the pervasive coordinating ability of the CCP and the dictatorial power of Xi.

China is big, Japan is small

Demographically, geographically, and economically, contemporary China couldn’t be more different from Imperial Japan, because the former is huge while the latter was small. Here, just for fun, is a visual population size comparison between the two countries (where population is proportional to 2d area):

China has 11 times Japan’s population, and 25 times its land area. There is just no comparison between the size of these countries. It’s like Germany versus El Salvador.

That means several very important things. First of all, it means that China would be a much, much more formidable foe in a war.

Japan lost its war against America the minute America decided to fight it. On the eve of war, Japan had about 35% of the U.S.’ per capita GDP, and about 55% of its population, for somewhere around 1/5 of its total productive power. As you might expect, America massively outproduced Japan during the war, and outnumbered Japan in terms of fighting men as well. Japan fought very hard, but after the first six months or so, the ultimate outcome was not in doubt.

Comparing modern China to the U.S., the per capita GDP ratio is not too different from the Japan-U.S. ratio in WW2 — about 22% in nominal terms and 36% in PPP terms (it’s not clear which matters more for military spending). But in terms of size, China dwarfs the U.S., with about 4.35 times our population. The U.S. would NOT be able to outproduce or outnumber China the way it outproduced and outnumbered Japan — in fact, it might be the other way around.

But at the same time, China’s bigness will also probably make it less interested in territorial conquest. Japan, being small, had to take over other countries in order to have the natural resources required to contend with other great powers. China might want to conquer Taiwan and take a few islands away from Vietnam or Japan or the Philippines for reasons of national pride, but it has much less of a need for conquest for the sake of resources.

That’s not to say China is fully self-sufficient in resources, of course; it’s not. It will need to guard its oceanic supply lines through the Indian Ocean and South China Sea, and develop alternative land routes as well (which is part of what the Belt and Road project is about). That could lead to conflict. But China doesn’t really need to go out and conquer anyone in order to become a great power; it’s already titanic.

China’s enormous size, coupled with globalization, also means that it’s much more central to the global economy than Imperial Japan was. Japan was a tiny peripheral player in international supply chains'; China is the world’s largest exporter and largest manufacturer, and the supplier of crucial tech equipment like 5G to much of the world. Economic integration doesn’t necessarily prevent wars — remember, Germany and the UK were each other’s largest trading partners on the eve of WW1 — but it could act as a brake on martial bellicosity.

Repression vs. conquest

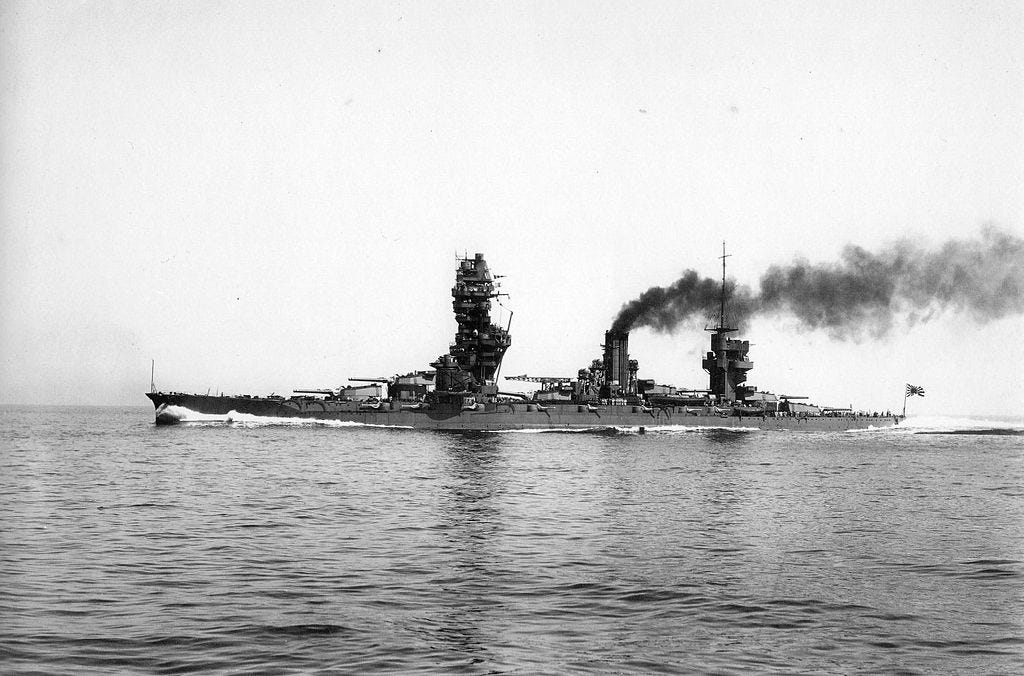

Japan’s need for resources and internal institutional and ideological ferment combined to drive it to seek external conquests — Taiwan, Korea, Manchuria, and then China and Southeast Asia. As a result, its military had a lot of experience in fighting wars, including more-or-less continual warfare during the 1930s. This made the Japanese military, especially the Navy, very competent. It also contributed to the dangerous sense of entitlement and independence among military units that ended up dragging Japan into wars, enabling numerous atrocities, and pissing off pretty much the entire rest of the world.

China, on the other hand, has been pretty much at peace since its failed invasion of Vietnam in 1979. Other than the minor “salami slicing” tactics of harassment and territorial encroachment in the South China Sea and the occasional bloody border clash with India, its military has little experience fighting wars. That could make it more cautious in terms of leaping into a major war over Taiwan or other disputed territory. It also, thankfully, means that China doesn’t have the unhinged destructive culture that the Imperial Japanese Army developed.

Instead of oppressing foreigners, China has been repressing its own people — surveilling everyone, crushing Hong Kong, putting Uyghurs in camps, and so on. It might be that China, like the USSR during parts of its history, is too busy with internal repression to go in search of external conquests.

So what does it all mean?

Summing up these big differences, I come away with two basic conclusions. First, China seems less likely to start a world war than Imperial Japan. China has much less of a need for external conquest, its military is not used to conquering places, and it has centralized, consolidated rule that will not let it be pushed into war by rogue factions. Other than a general sense of having been oppressed and humiliated by the West, China has none of the motives for war that Imperial Japan had.

BUT, if China does end up going to war with the West — or even have a protracted Cold War type struggle — it will be an infinitely more dangerous foe than Japan ever could have been. It’s far larger, with endless manpower and manufacturing capacity and vast stores of natural resources. And it has a fearsomely effective and centralized decision-making apparatus. The U.S. was able to overcome Imperial Japan alone, while fighting a two-front war; against China, it could probably only hope to prevail with a significant number of powerful allies.

Great article. Unfortunately, it doesn't seem as if pundits and our govt are thinking in terms of China as Japan but China as the USSR. Could you explore that? In my ignorance, I think they're making a serious mistake. China, unlike the USSR, doesn't pose an ideological threat at all and it poses even less of a military threat to friends in Asia than the USSR did in Europe. The logistics of modern war are so daunting that only the US can put even moderate forces overseas; I know of no evidence that China is making the effort to build up anything capable of conquering Taiwan.

>>>BUT, if China does end up going to war with the West — or even have a protracted Cold War type struggle — it will be an infinitely more dangerous foe than Japan ever could have been<<<

I've been reading Noah since he first started writing Bloomberg pieces, and I'm generally a big fan. But I find on geopolitics -- which in his case more often than not involves Asia -- his writing is like a teenager who's really, really (really!) enthusiastic about the board game Risk. Several hundred words comparing a potential Sino-US conflict with WW2's Japan-USA theater, and nary a word about the most obvious (and terrifying) difference between the PRC of then and the Japan of now: the former possesses a large, lethal and growing nuclear arsenal (and by their own admission are endeavoring to rapidly grow that arsenal). THAT is what makes a PRC-US war "infinitely" more dangerous than America and Japan's titanic struggle all those years ago. (A single nuclear weapon detonated over a US metro could easily cause more causalities than the country took during the entirety of its 57 month-long war against Japan). A Sino-US war in the Pacific isn't going to look anything like '41-'45. There will be no long, bloody slogs through tropical archipelagos that you can read about in the newspaper from the comfort of your living room. There will be no lengthy, multi-year stage when the economy is mobilized and production is ramped up in preparation for protracted campaigns. There will be no five million man army. And so on. Also, Japan had virtually no ability to hit the US homeland (well, there was a weaponized balloon that blew up over Oregon late in the war). That's very definitely not the case with China.

Very early on in such a conflict, one side or another (probably the side that's on the verge of losing) will either quit or go nuclear. A PRC-USA war (in addition to being as unthinkable* as a USSR-USA war was back in the day) will be short and unfathomably violent.

I suggest boning up on one's firemaking skills.

*Yeah, I know, somebody has to think about these things; but hopefully they do so mostly with an eye toward preventing them from occurring.