Chinese Demography

China is shrinking, and is about to shrink more.

In a previous post, I talked about why China’s neighbors are increasingly afraid of its overwhelming national power. So I thought I’d do a series of follow-up posts about China’s national power, and how it depends on various factors. The most important resource for any country is its people, so the first installment will be about China’s population.

Usually, discussions about Chinese demography are framed in terms of the question “Will China get old before it gets rich?”. That question has now been resolved; the answer is “yes”. It already happened. According to some sources, China’s median age is now higher than that of the U.S., and headed higher. China is thus now as old as a developed country, even though its income levels are less than half of developed-country levels.

And it’s getting older, thanks to low fertility. China, like all countries, used to have high fertility, but in the 1970s it started falling — well before the infamous one-child policy came into effect.

In fact, some Chinese demographers believe the fertility rate is being over-reported, and that the true rate is even lower. That would fit with a recent drop in actual birth rates.

But even if the official fertility number is right, it means China is going to continue to age very rapidly.

At some point, this will cause China’s population to actually shrink. This hasn’t happened yet, due to “population momentum”. But it’s close. Estimates of the peak range between 2023 and 2029.

But total population isn’t necessarily what matters for comprehensive national power. What matters is probably two things:

The number of working-age people

The percent of working-age people (or the dependency ratio)

The first of these is basically the number of people you have available to work. The second is the number of workers you have to support each dependent. The first is important because it affects how much the nation can produce; the second is important because it measures how much of that production needs to go toward supporting old people and children.

And for China, both of these things are already going down.

Working Age Population

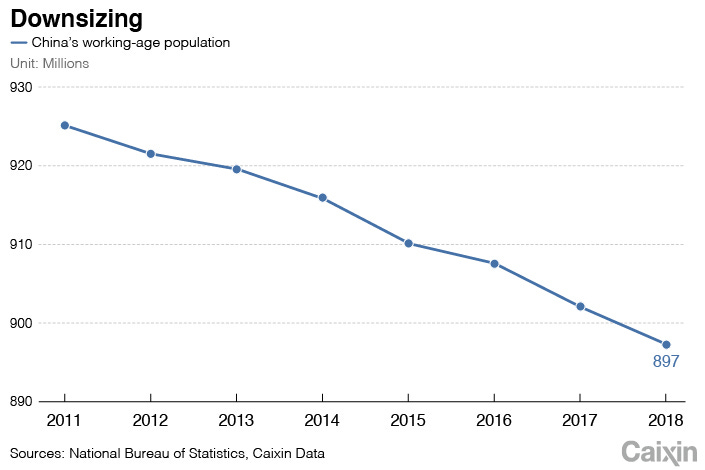

China has traditionally counted its working-age population as people between the ages of 16 and 59. After 60, people were generally encouraged to retire early (which makes sense, since much of the work in China was hard manual labor). By that measure, China’s working-age population has already shrunk by about 30 million since 2011:

To put this in perspective, China has basically lost more than one Canada’s worth of working-age people in the past decade. Of course, for a country the size of China, that isn’t much — a little over a 3% decrease.

But much bigger drops are coming. The Chinese government projects the working-age population to fall by about 65 million per decade for the next three decades.

Expanding the definition of working-age population to 15-64, as it’s typically defined in developed countries, means that the decrease is more gradual in the early 2020s:

Now, the farther you go into the future, the less reliable these projections are. In fact, recent forecasts suggest the drop in the latter part of the century might be even bigger. But I think it makes sense to confine ourselves to thinking about the next 30 years.

And for the next 30 years, China’s working-age population drop seems pretty much baked into the cake. The number through 2037 is pretty much set, since it takes about 17 years to make a new working-age person. The only thing China could really do to change the situation in the next 16 years is to let in a bunch of immigrants (which we’ll talk about in a bit).

As for the 15 years after that, it’s at least mathematically possible that China could arrest the decline with a higher birth rate. But so far the trend is decidedly in the opposite direction, despite government efforts to urge people to have more babies. Given the difficulty developed countries have had in reversing low fertility (even in authoritarian, well-managed Singapore), China’s chances of engineering a baby boom big enough to substantially reverse working-age population decline by 2050 seem remote.

In other words, China is going to shrink. And the economically productive part of China will shrink faster than the total. That will pretty mechanically erode China’s comprehensive national power. (Also, fewer young people means fewer potential soldiers, though China is huge enough that it will probably never lack in this regard.)

Fewer workers per retiree

It’s not just the number of Chinese workers that will shrink; it’s the percent. The older the country gets, the more old people whose consumption will have to be supported by the young. That includes eldercare, and it also includes any fiscal transfers like pensions and health care. That reduces the amount of production that can be used to build new capital, research new technologies, or build up the military.

As the Macquarie Research chart above shows, China’s percent of working-age population, even under the wider 15-64 definition, has already been in steep decline for a decade, and this decline is expected to continue unabated for the next 30 years.

In addition to diverting production away from growth and war-making, an aged population might reduce productivity. A number of studies suggest that workforce aging slows productivity growth. This is probably for a number of reasons — older workers become less productive toward the end of their careers, older managers may become ossified in their thinking and fail to innovate or seize new business opportunities, and so on. Automation mitigates this, of course, but it’s not clear it will mitigate it more in the future than it has in the past. On top of that, aging may exacerbate secular stagnation, and reduce agglomeration effects.

So there are a number of reasons why China’s rapidly shrinking and aging population will weaken it economically and militarily. The next question becomes: What can China do to change this situation?

Can policy reverse the decline?

As mentioned above, policies to get people to have more babies are very expensive, and have very modest effects. But some people believe the Chinese Communist Party has effectively total control over everything that happens in the country — if it forced people to stop having babies at gunpoint during the era of the one child policy, might it not simply be able to force people to have babies at gunpoint going forward?

Maybe. But raising children is simply so expensive in China that forcing families to have substantially more children might place them in economic hardship and lead to internal unrest. Furthermore, as the graph above shows, even the one-child policy itself was of dubious effectiveness — fertility had already been dropping for a decade before the policy, and actually didn’t fall much more in the decade after implementation.

Then again, maybe modern technology will make the Chinese government’s power over its citizenry go from legend to reality. Maybe some combination of social credit and universal surveillance will be able to gently but relentlessly nudge Chinese families to have more kids.

The thing is, the clock is ticking; even this desperate and extreme pro-natalist strategy wouldn’t bear fruit til late 2037, and if it takes 13 years to design and implement this strategy, well, that’s not going to change anything before mid-century. So China’s demographic cake looks pretty baked, unless it allows truly huge amounts of immigration.

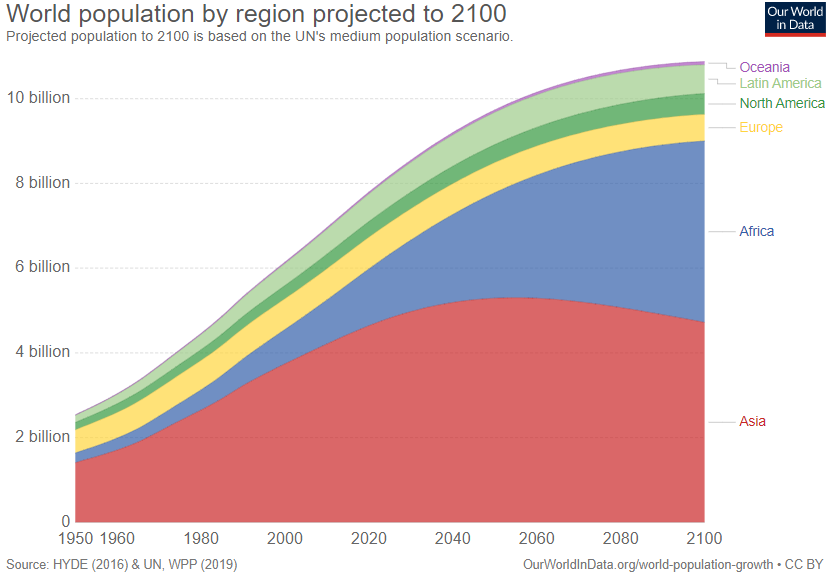

A small rich country like the Netherlands or a medium-sized rich country like Germany can pretty easily get enough immigrants to arrest or reverse population decline. But for China, which is 17 times the size of Germany and has living standards only one-third as high, it’s not so easy. To make a dent in population decline, China will have to let in truly vast numbers of immigrants from some of the poorest countries on Earth. That might include India in the short term, but in the long term it will have to mean Africa:

China’s government is trying to encourage more immigration, but public attitudes are ambivalent at best, and it seems unlikely that immigration will provide anything like the hundreds of millions of Indian and African workers that China would need to plug its demographic hole over the next three decades.

China will shrink, but it’s still enormous

So China will shrink, and shrink a lot, over the next 30 years. It seems conceivable that this might make the country more peaceful, as it is forced to turn its attention toward caring for the elderly, and as the absolute number of angry young men falls. But it also seems possible it will make the country more aggressive, as the government becomes anxious that it’s now or never in terms of conquering Taiwan and establishing regional or global hegemony. I don’t pretend to know.

But what’s certain is that even a shrunken China will still be enormous. Even if America takes the sensible advice of pro-immigration liberals like Matt Yglesias and continues to increase its population, China will still be well over three times its size through mid-century. And China’s continued preeminence over Japan, Taiwan, and other low-fertility neighbors will be just as pronounced, since these countries are shrinking as well. India will gain a little bit of power relative to China from its somewhat higher fertility, but its growth is slowing rapidly as well, and any advantage will be modest.

So China’s power will decrease a little bit due to aging. But not a huge amount. A shrinking, graying population is likely to alter the country’s domestic politics — in ways that are hard to predict — but it won’t make the country shrivel up and disappear.

____________________________________________________________________________

By the way, remember that if you like this blog, you can subscribe here! There’s a free email list and a paid subscription too!

Very thorough post on the age demographics, but I also wish there was more demographic discussion out there on China's linguistic/ethnic/cultural diversity and how that might play out this century. It seems to me that huge countries have problems keeping their very different groups of people united around a common nationality. We see that in the US today and in the past, we saw that in the USSR, and I'm just not sure China's huge size is not also a double-edged sword.

It surprised me, for example, how young people from Shanghai had a different (more negative) take on their government than

young people from Beijing. One Shanghai person told me they are proud to think differently and more freely than other people in China. It's interesting. 🤔

Now do India!