China has a fateful choice to make

The Ukraine war, Covid, and the real estate bust herald a crossroads for the world's biggest nation.

China’s stock market is in absolute chaos, suffering its worst crash since 2008. There are a ton of numbers I could quote, but here’s one that caught my eye:

The index rebounded a bit on Tuesday. But notice that while the most recent plunge was pretty steep, the downtrend has been going on for a while now.

One rule of being a financial pundit is that no one actually knows why stocks go up or down. A second rule is that everyone has an explanation anyway. And so people are rushing to explain this China crash as the effect of the Russia-Ukraine war:

Others cited “renewed regulatory risks”, meaning that the government is threatening to intensify Xi Jinping’s year-long crackdown on China’s tech industry.

There are also more long-term forces at work. As the ever-excellent Shuli Ren reports, many Western investors are questioning the value of being exposed to a country whose economic policy seems to lurch wildly and unpredictably. U.S. institutional investors have drawn down their holdings of Chinese stocks by almost a third, while some people in the finance industry are calling the country “uninvestable”. Marc Andreessen wondered aloud whether Westerners who hold Chinese shares really own anything at all:

In fact, I think all of these factors are likely to be part of the story, but each only grabs one piece of the proverbial elephant. More fundamentally, I see China at a crossroads, facing a basic choice about what kind of country to be. Economic upheavals, investor concerns, and geopolitical uncertainties all really radiate from the bifurcation of China’s future into two possible paths.

Four crises

China right now is facing four basic crises: Russia, industrial crackdowns, Covid, and real estate. If you already know all about these, you can skip to the next section of this post, but for those who are just now starting to think about China’s troubles, it helps to have a review.

The first crisis is Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Before Putin’s attack, China and Russia looked to be growing inexorably closer together, solidifying into a new axis that seemed to have the potential to outmatch the U.S. and its allies. But Russia moved too soon, and made the wrong move, and now China’s leaders don’t quite know what to do. On one hand, China’s state media have worked to promote Russia’s preferred narrative of the war — that NATO expansion forced Russia to act. But on the other hand, China’s ambassador to the U.S. angrily denied that China had any foreknowledge of the invasion. And Russia was reportedly furious when China’s ambassador to Ukraine praised the country’s resistance and vowed to help Ukraine rebuild.

China is really in a bind here. If Russia continues not to do very well on the battlefield, China faces an uncomfortable choice between A) standing back and letting its most important ally break its armed forces on a failed invasion, or B) intervening to help Russia subdue the Ukrainians, convincing the world it’s as monstrous as Putin and drawing the wrath of the sanctions regime that is crushing Russia’s economy. Its attempt to straddle the fence may result in the worst of both worlds — a shattered ally and international opprobrium.

The second crisis is China’s “regulatory” crackdown, i.e. Xi Jinping’s attempt to reorient the economy away from sectors he doesn’t think contribute positively to national strength. I’ve said a lot about this, so I won’t say much more except to note that this isn’t over — companies like Tencent are still being hit with massive fines for things China’s government had no problem with just a couple of years ago. Although the government is trying to compensate for the inevitable chilling effect on entrepreneurship by releasing TV shows lionizing semiconductor company founders, everyone in China who aspires to personal fortune has just gotten an unambiguous message that the government can take that fortune away from them whenever it sees fit.

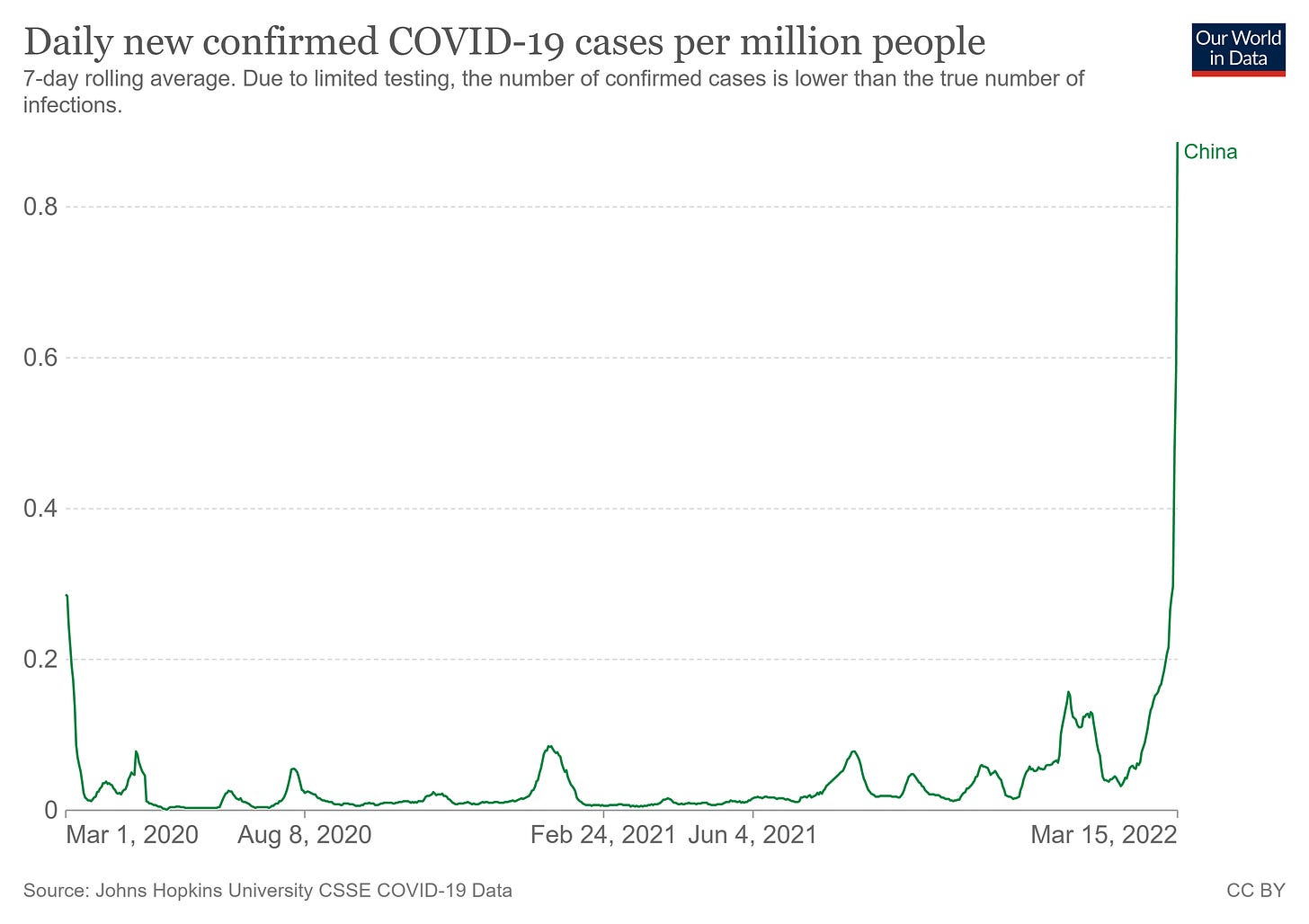

The third crisis is Covid. The hyper-contagious Omicron variant finally seems to have slipped its leash in China, and cases are going exponential:

Of course that’s still a miniscule number of cases compared to what the U.S. or Western Europe experienced. But unlike those other countries, China has committed itself to stamping out Covid utterly through non-pharmaceutical interventions. Thus, the new Covid wave has resulted in total or partial lockdowns of several of China’s largest and most economically important cities:

These lockdowns are already probably having major economic consequences — for example, Foxconn, probably Apple’s most important supplier, just shut down operations in Shenzhen.

And the insistence on Zero Covid — a policy nearly every other country has dropped — likely stems in part from public relations concerns. China has vigorously trumpeted its ability to suppress the original coronavirus through lockdowns and distancing measures — a success that both its leaders and its nationalistic boosters think of as evidence of the country’s superior system. To abandon that success now — never mind that Omicron is far more infectious than its predecessor — would be to see those pretensions of invincibility shattered (especially because Taiwan has been the one country to successfully contain Omicron so far). Also, China has refused to rely on Western-made mRNA vaccines, despite proof that these are far more effective than China’s domestically-made Sinovac — partly because it’s having trouble manufacturing those vaccines at scale, and partly because it invested considerable propaganda effort in claiming that the Western vaccines were worse.

So unless China does manage to stamp out Omicron, the lockdowns look likely to continue intermittently. Both the actual lockdowns and the uncertainty about them will put a chill on economic activity.

And China’s fourth crisis is the ongoing slow-motion collapse in the property sector. Although sparked by Xi Jinping’s desire to reduce the country’s reliance on the real estate industry, the collapse has taken on a life of its own, with a steady drumbeat of new defaults and bad news. Some excerpts from a recent Bloomberg update:

Home sales continue to plunge and elevated borrowing costs mean offshore refinancing is off the table for many developers. Global agencies are pulling their ratings on property bonds, while a string of auditor resignations is adding to doubts over financial transparency only weeks before earnings season. An 81% stock plunge in Zhenro Properties Group Ltd. highlighted the risks of margin calls as companies struggle to repay debt.

A gauge of Chinese property shares is down 3.4% this week, taking its losses over the past 12 months to 28%, even after rallying on Friday…China Fortune Land Development Co. failed to repay a $530 million dollar bond…Since [2020], at least 11 developers defaulted…Sales at China’s 100 biggest developers fell about 40% in January from a year earlier…Net financing, which subtracts [bond] maturities from issuance, was a negative $7.3 billion.

And so on. China is taking some measures to pump liquidity into the system, but pretending that a solvency problem is just a liquidity problem is a famously ineffectual measure (remember when we did that in 2008?). Ultimately, what China is going to do is a massive government-financed bank bailout. This is necessary, but it will also probably leave lending chilled for quite a while, and it’ll force lots of Chinese people in property-related industries to find other things to do. Both of those will weigh on growth, even after financial carnage stops.

So China is hitting a perfect storm of crises. But all of these crises actually stem in part from one single root cause — China’s incipient bid to overturn the liberal global order.

Two paths ahead

The liberal global order involves things like universal human rights, the inviolability of national borders, freedom of the seas, a taboo against wars of choice, a preference for democracy as a system of government, and the right of small nations not to be dominated by big ones. This system of values and the accompanying institutions that protect it have served the world very well since its creation in the wake of the Second World War, bringing about an era of relative peace and an unprecedented period of broadly shared economic development.

This order is not a euphemism for American power (or American/European power, or Anglosphere power). There’s no reason China can’t be the world’s most powerful country under a liberal global order. But the order does restrain China from doing certain things that its leaders and its nationalists desire — conquering Taiwan, claiming the whole of the South China Sea, and so on. And it does make it harder for Xi Jinping and Chinese nationalists to build the kind of society they seem to want — one where obstreperous minorities and dissidents are crushed with the heavy hand of the state, and where the activities and lifestyles of the broad populace are carefully policed.

Thus there are those in China who dream of overthrowing the liberal global order and replacing it with an alternative order of their own making. This would involve either vanquishing or cowing the U.S. and the other countries that defend the liberal order, or waiting for those countries to implode. And despite silly stereotypes, Chinese rulers and nationalists are not infinitely patient — they don’t want to trust that this will happen in 100 or 200 years, they want to see it happen in their lifetimes. (China’s low and falling fertility rates likely add some urgency to the calculus.)

And in the chaos created by Covid and Russia’s war, some of China’s nationalists see their chance. I was struck by some of the triumphalist language cited in a recent New York Times article:

China has laid the building blocks of a strategy to…benefit from geopolitical shifts once the smoke clears…At the heart of China’s strategy lies a conviction that the United States is weakened from reckless foreign adventures, including, from Beijing’s perspective, goading Mr. Putin into the Ukraine conflict…

[Xi Jinping] has repeatedly warned Chinese officials that the world is entering an era of upheaval “the likes of which have not been seen for a century.”…

In recent weeks, Chinese analysts have repeatedly cited the century-old writings of a British geographer, Sir Halford John Mackinder…[who wrote that] whoever controls Eurasia can dominate the world…

[A]version to international standards for political or human rights, supposedly dictated by the West, has become a recurrent theme in Chinese criticism of the United States. It was the subject of a government position paper in December, intended to counter a virtual summit of democratic countries held by Mr. Biden, and of a long statement that Mr. Putin and Mr. Xi issued when they met in Beijing last month…

“The old order is swiftly disintegrating, and strongman politics is again ascendant among the world’s great powers,” wrote Mr. Zheng of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen. “Countries are brimming with ambition, like tigers eyeing their prey, keen to find every opportunity among the ruins of the old order.”

What was the last time countries were “brimming with ambition, like tigers eyeing their prey, keen to find every opportunity among the ruins of the old order”? The 1930s. The “old order” of the time was the global power of the U.S., Britain, and France. And the tigers in question were Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan — nations brimming with a mix of pride in their supposed superiority and resentment over past humiliations, eager to claim their place in the sun.

We all know how that movie ended.

Finding opportunity in geopolitical upheaval, dominating Eurasia, dispensing with universal standards of human rights — these are all part of the same eagerness to overthrow the liberal global order. And this desire is manifesting in all four of the crises listed above.

It’s China’s desire for allies against the democratic powers that saw it turn to Russia, and which now forces it to waver and equivocate on what ought to be a clear-cut situation, drawing the suspicion of the world. It’s Xi Jinping’s vision of a martial society that led him to crack down on internet companies, video games, and pop culture — and on real estate. And it is Xi’s determination to prove China’s superiority that is forcing China to lock down in the face of Omicron while it seeks to reinvent mRNA vaccines. These problems all would have cropped up to some degree in any case, but the desire to supplant liberalism have exacerbated the costs China faces from each.

That path, however, is not the only path available to China. A recent analysis by Hu Wei, the deputy director of a Chinese government think-tank, provides a far safer and more sensible alternate vision:

[Putin’s] military action constitutes an irreversible mistake…The United States [will] regain leadership in the Western world, and the West [will] become more united…The new Iron Curtain will no longer be drawn between the two camps of socialism and capitalism…It will be a life-and-death battle between those for and against Western democracy…the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy will be consolidated, and other countries like Japan will stick even closer to the U.S., which will form an unprecedentedly broad democratic united front…

China will become more isolated under the established framework…it will encounter further containment from the US and the West…Europe will further cut itself off from China; Japan will become the anti-China vanguard; South Korea will further fall to the U.S.; Taiwan will join the anti-China chorus, and the rest of the world will have to choose sides under herd mentality. China will not only be militarily encircled by the U.S., NATO, the QUAD, and AUKUS, but also be challenged by Western values and systems…

China cannot be tied to Putin and needs to be cut off as soon as possible…Cutting off from Putin and giving up neutrality will help build China’s international image and ease its relations with the U.S. and the West. Though difficult and requiring great wisdom, it is the best option for the future…

China should prevent the outbreak of world wars and nuclear wars and make irreplaceable contributions to world peace…To demonstrate China’s role as a responsible major power, China not only cannot stand with Putin, but also should take concrete actions to prevent Putin’s possible adventures…As a result, China will surely win widespread international praise for maintaining world peace[.]

In other words, Hu advocates that instead of trying to overthrow the liberal order, China become its chief enforcer — thus setting itself up to take over as the centerpiece of that order, as the U.S. once took over from Britain. He’s only talking about Russia/Ukraine here, of course, but it’s easy to imagine applying the same idea to China’s other problems — embracing Western mRNA vaccines while working to develop its own capability in the future, and focusing its industrial policy on scientific and technical leadership instead of trying to crush any industry that doesn’t have obvious direct benefits for hard power.

It’s a smart strategy. It would work. The U.S. could not long hold its pole position within the liberal global order against a fully industrialized high-tech country with four times its population; as the global guardian of liberalism, China would naturally be first among equals.

But I’m not holding my breath for Chinese leaders or nationalists to see the light here — Hu’s essay was quickly banned on Chinese social media. As for Xi Jinping, he seems to have been getting a bit high on his own supply of propaganda — he truly came out of 2020 believing that China had worked out a superior system and that liberalism was now an albatross around his enemies’ necks. He appears set on indulging his conservative nostalgic vision of what his country ought to look like.

Nor is Xi the only important actor here. An angry, chauvinistic nationalism has become a deeply rooted force in China’s society. Even as China’s government has wavered on whether to support Putin, there has been a massive outpouring of support for the invasion on Chinese social media. Of course that nationalistic sentiment isn’t unanimous, and it’s hard to tell what percent holds it, but for now they seem to have the upper hand. In fact, at this point it’s not clear that China’s top leadership could stop the nationalist tide even if they wanted to; like the generals of Imperial Japan, they could end up getting pushed into aggressive action by a populace that had no idea of the risks.

So China stands at an epic crossroads. It faces a choice that will determine its fate for the rest of the century — the choice of whether to return to the path of stability that Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, and Hu Jintao set it on, or whether to gamble it all to try and succeed where the revisionist illiberal powers of the 20th century failed. The stock market is only the latest messenger issuing a warning that the latter course would be extremely ill-advised.

Great analysis Noah. I might add the report today about possible FSB document leaked discussing Xi's intention at invading Taiwan this past fall. It's incredibly relevant, if true. Especially to myself, as I'm situated in Taiwan.

Keep up the great work, cheers.

Xi looks likely to push China down the strongman route. It’s the rare authoritarian who doesn’t get high off their own supply. Sad (and, frankly, irrational) as that may seem.