Can we actually "brain-drain" China?

No. But we can give America a big economic boost while boosting our moral image.

There’s an idea going around in some policy circles that the United States can “brain drain” China by getting its best and brightest to move to the U.S. — in other words, that high-skilled immigration policy could be used as a competitive strategy for Cold War 2. Caleb Watney, for example, tweets:

Watney wrote a piece at The New Atlantis laying out the idea in greater detail. It’s a very good piece, and you should go read it. Watney recaps the U.S.’ history of taking in waves of highly skilled scientists at its rivals’ expense — Jewish scientists who fled Nazi Germany, Operation Paperclip (in which the U.S. and USSR competed to kidnap Nazi scientists), Soviet defectors in the 1980s, and so on. He marshals evidence that these scientists made critical contributions to U.S. technological supremacy. The most famous example of this is the foreign-born scientists who invented nuclear weapons for the U.S. (including Edward Teller, pictured above, who invented the hydrogen bomb).

Why immigrant scientists are so important

I happen to know a bit of that literature on high-skilled immigrants and innovation, so here are a few papers:

1. “German-Jewish Emigres and U.S. Invention”, by Petra Moser, Alessandra Voena, and Fabian Waldinger — This paper finds that chemists fleeing the Nazi regime raised U.S. patenting substantially in the fields they worked in.

2. “Immigration and Ideas: What Did Russian Scientists “Bring” to the United States?”, by Ina Ganguli — This one looks at paper citation counts, and finds that Russian scientists fleeing the USSR led to academic booms in the fields they worked in.

3. “Immigration and the Rise of American Ingenuity”, Ufuk Akcigit, John Grigsby, Tom Nicholas — This paper shows that fields that had more immigrant inventors between 1880 and 1940 had both more patenting and more academic citations between 1940 and 2000.

4. “The Supply Side of Innovation: H-1B Visa Reforms and US Ethnic Invention”, by William R. Kerr and William F. Lincoln — This one shows that increasing the H-1b visa cap led to influxes of Chinese and Indian workers who increased innovation in the cities and companies they went to.

5. “Skilled Immigration and Innovation: Evidence from Enrolment Fluctuations in US Doctoral Programmes”, by Eric T. Stuen, Ahmed Mushfiq Mobarak, and Keith E. Maskus — This paper finds that when negative macroeconomic shocks in other countries sent more grad students from those countries to the U.S., productivity at the U.S. laboratories they worked in rose significantly.

This literature goes on, and its conclusions are not ambiguous — when the U.S. gets an influx of foreign researchers, U.S. innovation goes up. This is one of a number of reasons why I’m always calling for the U.S. to increase its inflow of high-skilled immigration.

Watney goes further. He frames high-skilled immigration as a competition between the U.S. and China, noting that China has been trying to do something similar to the U.S., with programs like the Thousand Talents Program. This uses various perks and financial incentives to lure Chinese scientists working in the U.S. to leave and move back. But as a Brookings report by Remco Zwetsloot shows, this is far from China’s only program in this regard. There’s a whole network of professional organizations and corporate incentives designed to attract returnees, as well as scholarships that require Chinese students to return after getting their degrees.

Watney calls for the U.S. to battle back, by reforming its skilled immigration system in order to compete for Chinese talent. He suggests the creation of a new “Department of Promigration” to encourage foreign researchers to come to the U.S. In a separate report for the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Zwetsloot suggests a whole raft of reforms that would make the U.S. more competitive in terms of attracting international talent.

All of these are very good suggestions. From the 1980s through the early 2010s, the U.S. didn’t have to do anything to encourage top scientists and inventors to move here — we were the obvious destination. Now, with our image tarnished, immigration is falling; we will probably have to actively compete for talent that in the past would have fallen right into our lap. And Watney and Zwetsloot both have good ideas for doing that.

But I think we need to distinguish between three objectives here:

Objective 1: Attracting skilled immigrants in order to boost our economy

Objective 2: Attracting skilled immigrants in order to strengthen our innovative capacity vis-a-vis China

Objective 3: Brain-draining China of its best scientists and engineers in order to secure a competitive advantage

The first two of these actually dovetail pretty strongly; the only difference, perhaps would be whether to target programs toward immigrant entrepreneurs or immigrant scientists. But basically, Objective 1 and Objective 2 both just say “Attract as many foreign scientists as possible”. This is very doable and we need to do it.

But Objective 3 is going to be much, much trickier.

Why brain-draining China will be very hard

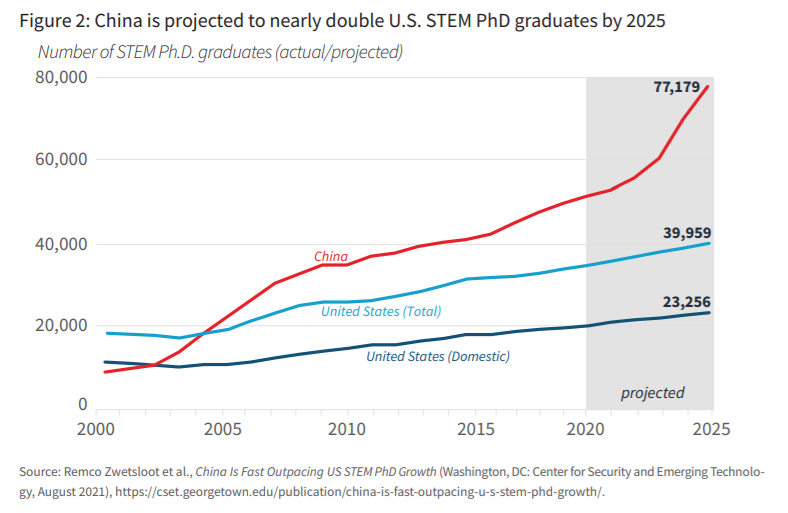

The first reason brain-draining China will be hard is that it’s just so huge — much larger than either the USSR or Germany were. It has four times our population, and it’s minting new STEM PhDs faster than we are:

Any brain drain strategy will merely be a sip from that mighty torrent.

But an even more fundamental issue is that brain drain, in general, is a myth. It just doesn’t happen, under normal circumstances. The Nazis, who lost a lot of their best scientists and suffered grievously when they pushed out Jews and liberals, are really the exception here. Usually, skilled immigration sets up a virtuous cycle that benefits both the sending country and the host country.

There are several mechanisms by which what looks like “brain drain” is actually usually “brain gain”. First of all, the opportunity to send researchers abroad can encourage education and high-tech investment in a developing country. Also, scientists, entrepreneurs, and engineers who leave their country to work in another country often return home after a while, bringing back their knowledge and human networks and personal fortunes. But crucially, even if they don’t go back, diaspora scientists often share their knowledge and ideas with people they know back in the old country, which boosts innovation there. A recent paper by Qingnan Xie and Richard B. Freeman finds:

Chinese diaspora authors of scientific papers…produce a large proportion of global scientific papers of high quality, gaining about twice as many citations as other papers of the same vintage…[D]iaspora researchers are a critical node in the co-authorship and citation networks that connect scientific discovery in China with the rest of the world. In co-authorship, diaspora researchers are over-represented on international collaborations with China-addressed authors. In citations, a paper with a diaspora author is more likely to cite China-addressed papers than a non-China addressed paper without a diaspora author; and, commensurately, China-addressed papers are more likely to cite a non-China addressed paper with a diaspora author than a non-China paper without a diaspora author. Through those pathways, diaspora research contributed to China’s 2000-2015 catch-up in science and to global science writ large, consistent with ethnic network models of knowledge transfer, and contrary to brain drain fears that the emigration of researchers harms the source country.

In normal times, this is great. It creates a virtuous cycle wherein both the U.S. and the sending country see their rate of innovation increase. Everyone wins.

But if we’re now in a zero-sum competition with China, this doesn’t make sense. Just as facilitating Nazi or Soviet innovation would have been unacceptable during our contests with those rivals, helping China do cutting-edge research would not be a very effective way of prosecuting Cold War 2. In fact, making U.S. science dependent on researchers who tend to share their results with our chief rival doesn’t seem like a smart move.

The instinct, then, would be to invite Chinese researchers over, but try to prevent them from leaking ideas back to China. But this opens up a huge new can of worms. Over the past few years, the U.S. has gone on a giant spy hunt, scrutinizing Chinese researchers for signs of illicit technology transfer. Dan Wang writes about how this effort has turned up relatively few cases of actual spying, while driving talent back to China:

Most defendants in these cases are of Chinese origin or descent. Recent reporting in MIT Technology Review suggests that only a quarter of the cases brought under the China Initiative involve alleged intent to steal secrets or spy. The bulk of the prosecutions of the past three years…are related to a lack of candor, such as the failure to disclose ties to Chinese funding or institutions…[A]cademics have been subjected to house arrest, the loss of their jobs, and ruinous legal fees…

Overkill has consequences. In a study conducted by the University of Arizona and the Committee of 100, a nonprofit representing prominent Chinese Americans, 42 percent of surveyed Chinese scientists reported that the China Initiative, and other investigations by the FBI, has affected their plans to stay in the U.S…According to the Chinese government’s figures, the share of overseas students who decide to return climbed from a low of 25 percent in 2005 to 64 percent in 2018.

So the U.S. faces a dilemma. Attracting Chinese scientists leads to collaboration between them and scientists back in China, which ends up transferring ideas to our rival. But trying to prevent this collaboration just drives the researchers away and makes the U.S. look like the bad guy. It even strengthens some people’s impression that the U.S. is engaged in racist persecution of Americans of Chinese heritage.

What we can do

Facing this Catch-22, what can the U.S. do? In general, my rule is: “Be the good guy.” And in a cold war situation, that means creating meaningful, substantive moral distinctions between ourselves and our rivals.

Chinese scientists get plenty of perks and resources back in China. But what they don’t get is freedom. China never had anything approximating the U.S. notion of free speech, but in the Xi Jinping era, crackdowns on dissent have ramped up to a fever pitch. Academics tend to be the type of people who value independent thought and the ability to speak their minds, and this makes them a natural target for persecution by Xi’s regime. Already this has driven an offshore exodus of scholars in law and political science.

But STEM researchers are not simple gearheads who care only about their equations and blueprints, and nationalism will only motivate some fraction of them to toe the party line. Many scientists and engineers are going to resent having to live in constant fear of going from well-funded government darling to prison cell occupant if they say the wrong thing about Xi’s policies.

And here is where the U.S. has an opening. We should use the asylum system to explicitly encourage defections of scientists and engineers from China, offering them permanent residence (and eventually citizenship) for relocating to the U.S. This doesn’t have to be done secretly or clandestinely — it can be trumpeted openly, by the President of the United States, along with explanations of why scientists might feel safer in America than in China.

Defectors, as a group, will not be the type to ship U.S. secrets back to Chinese government-supported enterprises — at least, not while Xi or someone similar remains in power. In fact, there’s a chance that China’s government itself might try to stop defectors from collaborating with people back in China, since they might spread their subversive ideas along with their scientific ones.

In other words, trumpeting American freedom as a way to lure scientists permanently away from China will both reinforce the U.S.’ moral image in the world, and gather needed tech talent in a way that doesn’t encourage the sending of ideas overseas. Of course, that effort would have to be paired with vigorous efforts to present the U.S. as a place where Chinese people can feel safe and free from racial discrimination. That will require cracking down further on anti-Asian hate crime, as well as stepping up rhetorical efforts to make Asian immigrants feel like America cares about them and can be their family’s permanent home.

But it’s worth it. America needs talent to innovate and grow, and China has a lot of it. We can get that talent and burnish our moral credentials as defender of the Free World at the same time.

The issue which is not addressed well in this article is: how much of the US' attractiveness to skilled immigrants was due to its economic dominance? The US economy was something like 40% of the world's GDP after World War 2 - why wouldn't a smart guy move to the US to take advantage of the economic opportunities in a large, rich, undestroyed by war, country?

The equivalent today is: China has been the fastest growing opportunity in the world for the past generation. They are, or will soon be, the largest economy in the world.

I also see a distinct oversight: the Nazi rocket scientists and Japanese medical experimenters.

Why the competition between US and China must be a zero-sum game? This will just narrow our mindset and force the response from both countries into a loss-loss situation. It’s a real waste of resources and an increase in inefficiency for the whole world. Americans should be more open-minded and spend time in China to understand the country and its people.