Under President Biden, the U.S. has embarked on a breathtakingly ambitious new economic program. With the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS Act, we’ve made a clean break with the Reagan-Clinton “neoliberal” era and turned toward industrial policy. That’s an intellectual victory, but it’s not yet an economic victory. Simply deciding to do things differently isn’t enough; you have to actually produce results, our your new program is a failure.

In the case of Biden’s industrial policy, the test of success will be whether green energy and semiconductors actually get built. I see three possible outcomes here:

Outcome 1: A lot of green energy and semiconductors get built.

Outcome 2: A lot of government money gets spent, but little green energy and few semiconductors get built, because the process is held up by a combination of regulation, NIMBYism, onerous project requirements, skilled labor shortages, and excess costs.

Outcome 3: A combination of GOP political opposition and regulatory/cost barriers prevents government money from even being spent in the first place.

Outcome 1 is a complete success, while Outcome 3 is a complete failure. Outcome 2 is the most complicated case. It would be a short-term political success, and it might please the array of Democratic interest groups into whose pockets the government money flowed. But because it doesn’t result in the building of goods that are useful to the average American, it would be an economic failure. And ultimately that economic failure would translate into a long-term political failure, as the vast majority of voters who don’t belong to Democratic interest groups decide they’re not really getting anything for their money, and decide to ditch Bidenomics and go back to Reaganomics for another two generations.

So I think it’s a good idea for proponents of industrial policy to try very hard to avoid Outcome 2. Ezra Klein agrees, which is why he’s been championing what he calls “supply-side progressivism”. This is basically the notion that the goals of a progressive industrial policy — for example, decarbonizing the economy — should take precedence over the methods we use to reach those goals. Ezra believes we should try to boost unions, hear out community groups, and so forth, but not to a degree that actually ends up scuttling the industrial policy itself. I can’t help but agree.

Klein’s critics in the progressive movement — the writer David Dayen, the people at the influential Roosevelt Institute, etc. — have an unfortunate tendency to grievously mischaracterize his arguments, claiming that “supply-side progressivism” means repealing the Clean Air Act and workplace safety laws, canceling democracy, kicking unions and environmentalists out of the progressive movement, locating “unwanted infrastructure” in Black neighborhoods, and so on. In fact, as Eric Levitz explains in a recent column, these accusations are all specious — they are either entirely invented out of thin air, or directly contradict things Klein has written.

But bad-faith caricatures aside, there is some real substance to the dispute here. Consider the role of unions, an important Democratic support group that will almost certainly play a major role in the implementation of industrial policy.

Unions don’t always make it harder to build — but sometimes they do

Consider the case of the TSMC factory in Arizona. This factory, built by the world’s top chipmaker, is central to Biden’s plans for a revitalized U.S. semiconductor industry. But this flagship project has now been delayed by one year, due to a lack of American workers who know how to build semiconductor fabs:

TSMC Chairman Mark Liu told analysts on an earnings call Thursday that the company does not have enough skilled workers to install advanced equipment at the facility on its initial timeline. The company previously anticipated it would begin making 5-nanometer chips in 2024.

Liu said the company is working to send technicians from Taiwan to train local workers to help accelerate installation.

This is obviously not the kind of worker shortage that can be solved simply by raising wages. You could pay me $10,000,000 a year to install chip fab equipment, and I could eventually learn how to do it, but it would take a while. And I couldn’t learn it from reading Wikipedia; I would need someone to train me who has done it before. These are, after all, some of the most complicated machines ever built by humanity.

America simply doesn’t have a lot of people who know how to install this equipment, because we haven’t built many chip fabs for a long time now. That’s why TSMC is flying out their own people to train American workers and help with the installation.

But, maddeningly, some U.S. unions are now trying to block these Taiwanese workers from coming to the country!

Controversy over the first ever US TSMC plant aren’t going away – especially plans for around 500 Taiwanese construction workers to be flown in.

A petition has been created, calling on senators and members of Congress to block the visas needed to bring in their foreign workers…The company says that these workers have experience of setting up similar plants in Taiwan, so will help with faster and more cost-effective working.

However, unions say it breaks a promise to create jobs for American workers…The Arizona Pipe Trades 469 union has started a petition to block the issuing of these visas.

This is, in a word, nuts. American pipefitters simply do not know the technical details of installing ultraviolet lithography machinery. They need someone to teach them before they can do it, and the people who can teach them live in Taiwan. Blocking these overseas workers doesn’t help anybody, least of all American workers, who will be left without wages if no factory gets built.

So it’s clearly possible for unions to block industrial policy from working. Nor is this the only such example; witness the union attempt to stop ports from using automation, even as supply chain snarls drove up inflation. And yet at the same time, both U.S. history and the recent experience of other countries shows that unions don’t have to be a barrier to high-tech manufacturing.

First, let’s look at history. Perhaps the most successful industrial policy in U.S. history was the World War 2 effort, which turned the U.S. into the world’s dominant high-tech manufacturer. This awesome success coincided with a historic rise in the fraction of unionized workers, thanks to a pair of laws the Roosevelt Administration passed in 1933 and 1935 that made collective bargaining easier.

The Roosevelt administration certainly clashed with unions on occasion during this time period, and strikes did disrupt wartime production to a small extent, but overall the relationship between unions and the government was a constructive and effective one. The progressive goals of unionization and broadly shared prosperity were ultimately aligned with the industrialist goals of winning WW2 and building up U.S. high-tech manufacturing.

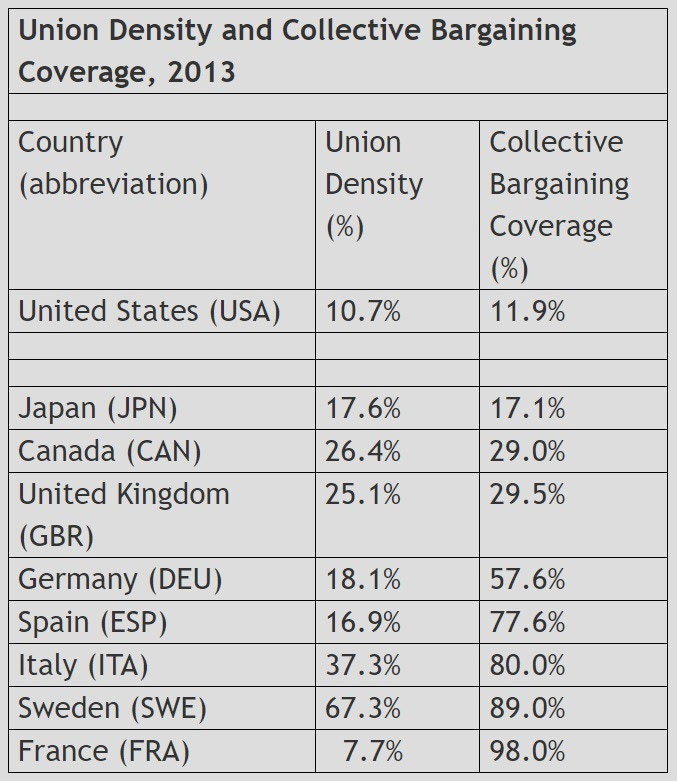

Of course, that was a long time ago, and technology has changed. But there’s little reason to believe that unions are incompatible with high-tech manufacturing in the modern day. Consider the fact that countries like Germany and Japan have considerably higher unionization rates than the U.S., and Germany has much higher rates of collective bargaining coverage, due to something called sectoral bargaining that lets even non-union workers be covered by union agreements:

But despite much higher unionization rates, both countries still have much more of their economy dedicated to manufacturing than the U.S. does, and have deindustrialized much less than the U.S. has over the past two decades:

That doesn’t mean there’s no conflict between labor and management in those countries’ manufacturing industries. Germany’s famed “mittelstand” manufacturers, for instance, often try to get out of the country’s requirement that labor be given board representation (a policy called “co-determination”). And unionization has declined over time in both Japan and Germany, due to the pressures of globalization. But these countries’ success in manufacturing relative to the U.S., despite their higher collective bargaining coverage, indicates that unions are not incompatible with manufacturing excellence.

Nor is this the only such example we should look at. Some people try to blame unions for America’s higher infrastructure costs relative to other developed countries. But those countries are actually much more unionized than the U.S., and their unions are politically stronger as well. Alon Levy, who has made a more careful study of infrastructure cost differences than perhaps any other human being alive, concludes that little of the cost differential is due to unions. U.S. construction wages aren’t even much higher than wages in other countries. Although union rules in some regions do force transit agencies to hire too many staff, Levy concludes that this is a minor factor.

In other words, strong unions are very compatible with cheap infrastructure construction — which is exactly what we need to decarbonize America.

Unions shouldn’t go away, but some of them need to change their approach

In other words, unions do impose some cost on industrial policy, but it doesn’t have to be a crippling or prohibitive cost. And as the example of World War 2 show, there are political benefits of aligning the interests of labor and industrialist planners. And there are signs that those political benefits are still achievable today — witness how the shift of many unions to the YIMBY camp in California was what enabled many of the pro-housing bills now being passed by the state legislature.

Thus, there is no reason to think that union-busting should be a part of our industrial policy, or that unions should be expelled from the progressive coalition. At the same time, the examples of the Taiwanese construction workers and resistance to automated ports show that American unions sometimes really do act in ways that frustrate the goals of progressives and industrialists alike. If industrial policy is to succeed, they need to stop doing that.

Supply-side progressives therefore need to think of ways to align the interests of the unions and the industrialists. That might involve giving labor more of a seat at the table when making industrial policy, so that unions understand that new technologies and foreign workers aren’t threats to their livelihoods. That could mean some variant of German co-determination, or simply including a few prominent union leaders in the planning process for the implementation of the CHIPS Act and the IRA. The goal here is to get American unions out of the wild-eyed defensive crouch that they’ve been in for the last 40 years, and convince them that things that they previously perceived as threats — new technologies and foreign workers — now represent opportunities instead.

Meanwhile, the people at the Roosevelt Institute need to stop acting like every criticism of union behavior is a prelude to union-busting and a fracturing of the Democratic coalition. That kind of panicky reaction is also a sort of defensive crouch, born of the Clinton years when the only way Dems could win elections was by making concessions to Reaganomics. It’s not 1996 anymore; progressives are now setting the economic policy agenda. They can afford to tell unions “No, don’t do it like that, do it like this instead” without seeming weak and disunited.

Ultimately, people like David Dayen and the Roosevelt Institute people are right that progressive industrialism needs to build power in order to succeed. But the power to merely appropriate resources from the federal government is far inferior to the power to create prosperity out of nothing for the whole country. That is something the supply-side progressives understand, to their great credit.

My thoughts, from many decades in the union movement and six years as head of the AFL-CIO in Oregon:

-The single-employer, site-based bargaining unit, a product of those 1930's New Deal laws Noah cites in this piece, are woefully outmoded and mis-structured for today's economy, whether we pursue industrial policy or not.

-That's why we need sectoral bargaining.

-These outmoded structures infect the organization of the union movement as well. Unions are federations of local chapters, thus the actions of the Arizona pipe fitters, which may run counter to the views of their national leadership. The many tails of any national union often wag or disorient the dog in instances like this, pitting parochial biases and short-term interests against the broader and longer-term interests of workers in a given industry.

-Sectoral and regional bargaining would help to force unions to restructure and better deal with the dynamics of today's economy.

-The union movement continues to press for labor law reform to make organizing easier, without pursuing parallel reforms to change the structure of bargaining to be multi-employer, multi-site and therefore sectoral. The labor law reform agenda needs to add a focus on the latter.

-There remain two types of unions in the U.S. -- craft unions (like the pipe fitters Noah mentions in AZ and all of the building trades unions), which preceded the New Deal (think of Samuel Gompers and the cigar makers), and industrial unions like the auto workers, which are a product of the New Deal. The former (AFL) are supply side unions, based on apprenticeship and their ability to deliver a highly-skilled workforce to multiple employers. The latter (CIO) are industrial unions, structured on a non-craft, all-workers, "wall-to-wall" model, but still largely dependent on localized bargaining units focused on sharing the profits of single employers.

-If we progressives hope to build back better, we'll need to pay more attention to the benefits of the apprenticeship model of the craft unions (on a regional basis) and the need to reform the outmoded bargaining unit structure of the industrial unions (on a sectoral basis). Those changes will require more than new approaches to unionizing and representing workers by the unions themselves. Some unions have been pioneering new ways of representing workers in specific industries, like the Service Employees' Justice for Janitors and home care workers campaigns, but that approach won't get to scale with a new legal framework enacted at the national level. Unions should move beyond trying to regain their power for workers through an outmoded structure and Democrats should stop treating labor law reform as an "oh yeah, that" agenda item. There are big changes needed that will take a concerted effort, like, for example health care reform.

Respectfully Noah, this piece is a little empty. Unions in most countries and most times throughout history have been anti-automation, anti-foreign workers, and frequently anti-progress. They are philosophically always, always protectionist. Advocacy for extremely narrow interest groups (dockworkers, cargo ship deckhands) imposes large costs on the other 99.9% of the working population. Everyone in America is paying for the Jones Act giving job security to a few thousand workers!

>That might involve giving labor more of a seat at the table when making industrial policy

So they have even more political power to block progress?

>and convince them that things that they previously perceived as threats — new technologies and foreign workers — now represent opportunities instead

Frequently they really are a threat to their very narrow interest group- automation really will put some dockworkers out of work, machines really did displace the Luddites. The bird's eye view is that it's better for society overall for some workers to lose these jobs, sorry to say. Pain for narrow interest groups leads to diffuse benefits for everyone