Book review: "One Billion Americans", by Matt Yglesias

MOAR.

Back in 2013, my PhD advisor Miles Kimball wrote an article for Quartz suggesting that in order to outmatch China in terms of geopolitical clout, the U.S. needed to let in lots of immigrants. I hadn’t really thought of immigration in those terms — I was always more about the economic and cultural benefits, and the idealism of America as a “nation of immigrants”. But Miles persuaded me that national power was an additional factor. As China becomes more authoritarian and more aggressive internationally, it needs someone to balance them. When it comes to national power, size matters; even the richest, most well-run country can’t do much if it’s up against a halfway competent country 10 times its size. As long as mass immigration is a good thing for the U.S. anyway, why not use it as a way to bulk up to a size where we can stand toe to toe with our soon-to-be-rival?

Now, Matt Yglesias has written an entire book expounding this thesis, and providing a road map for how to bulk America up. It is a very good book, and you should buy it.

In this review, I’ll offer a few thoughts on why the book is good, and where I would have liked to have seen the arguments and ideas fleshed out more. But basically, this is a solid case for much much more immigration, at a time when anti-immigration policy has gotten the upper hand.

Why make America bigger?

Matt’s basic pitch is this: China is big, so if the U.S. wants to be as powerful as China, we also need to be big.

Americans often seem not to realize, on a deep and visceral level, just how honkin’ big China is. Here is a graph showing the two countries’ populations in 2020:

In terms of population, China is bigger than the U.S., all of Europe, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Canada, and Australia combined.

Obviously, any contest of power between the two will also depend on their relative wealth, technology level, government competence, military competence, etc. But China is increasing its wealth and technology level all the time, and the recent COVID-19 episode should give us some information about the two countries’ government competence (It’s not all bad news for us; we developed very spiffy vaccines in record time. But it’s mostly bad news for us.). In others words, the advantages that would allow the U.S. to prevail in any sort of contest against China — military, economic, technological — are rapidly eroding. And that implies that we should offset our big disadvantage in population, by bulking up.

In fact, there’s another reason that population would make America stronger, which Matt doesn’t really go into: Agglomeration effects. Companies are desperate to invest in China because of that huge domestic market. The lure of that market forces them to put up with a lot, such as Chinese IP theft. It also induces them to put factories and offices in China, which creates lots of jobs for Chinese people. And when some companies put their factories and offices in China, it induces other companies to do the same, since they need to be located near to their supply chains — if the battery makers are in China, it makes sense for the phone makers to be in China too, etc. If the U.S. had a larger population, we could be an even more attractive destination for investment — we could retake our position as the “economic center of the world.” That would make us richer as well as cementing our power vis-a-vis China. I would have liked to have seen more of an explanation of agglomeration in the book.

OK, but let’s step back. Why are we trying to stand down China at all? Why is this a goal? Is Sweden letting in immigrants to try to balance Germany? Is Bolivia letting in immigrants to try to balance Brazil? And so on. Aren’t international conflicts bad? Aren’t cold wars bad? Can America even claim to be the good guys on the international stage anymore, after Iraq and Trump?

Now, I, Noah Smith, can give you answers to this question. I can talk about China threatening the freedom of Taiwan and other countries in the region. I can talk about how America, despite our recent stumbles, still has the DNA of freedom and individual dignity, and can advance these values in the face of a Chinese state that offers people only economic stability at the cost of dignity and freedom. I could talk to you about those things. But Yglesias doesn’t talk about them in this book. And so I feel that he needs to write a follow-up book, to explain why this contest is one we should even enter.

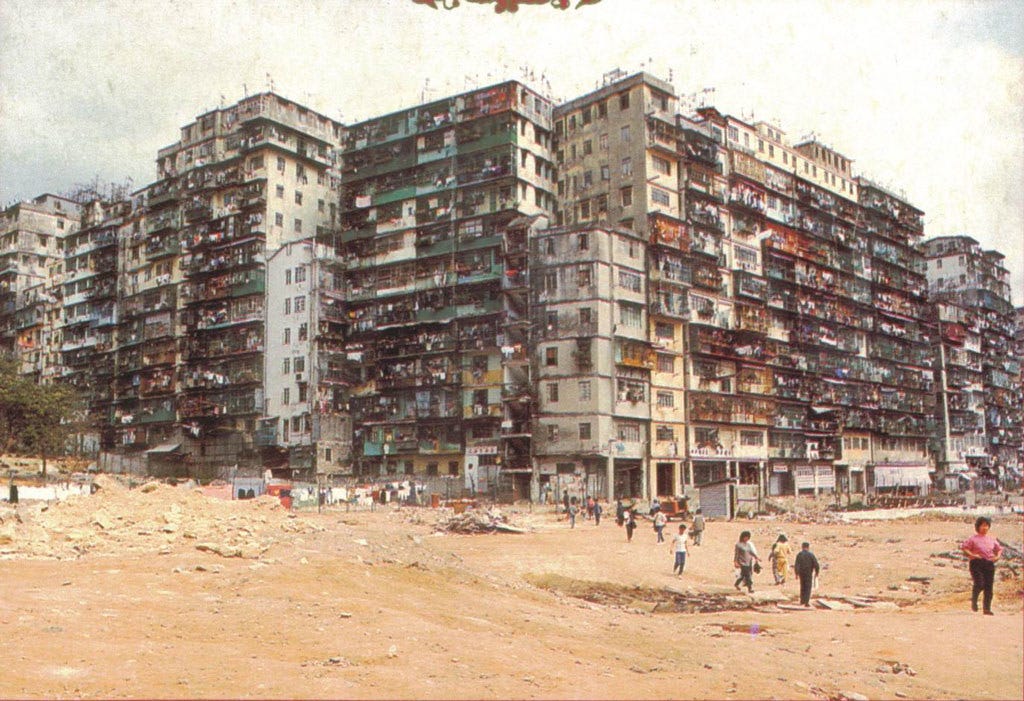

Visions of Dense America

The most powerful fact in One Billion Americans is that if the U.S. actually had a population of one billion, it would only be as densely populated as France. A lot of opponents of density talk as if we’d all have to live in little pods and eat bugs. I imagine they think that an America of one billion people would look something like this:

But in fact, lots of France just looks like this:

A billion Americans would only be three times the number of people we have now. That’s a point Yglesias really drives home, and it’s the most powerful part of the book. But I think it could have used some pictures, frankly, to show that France-like density isn’t so bad after all.

How to fit all those people

Just importing a few hundred million people, however, would not automatically make America as picturesque of a country as France. Current land use is based around suburban sprawl, long commutes, polluted freeways, cookie-cutter suburbs, and other bad choices. Much of Yglesias’ book is dedicated to explaining the nuts and bolts of how we could reshape the U.S. to fit all those new people.

Basically this is just a question of urbanism — land use and transit. We need to create denser neighborhoods that are still livable, while preserving people’s ability to get around easily. This is where Yglesias’ knowledge really shines, as he has been thinking about these issues for literally decades. He’s an urbanist at heart, and here he returns to his roots.

It’s a little odd to position three chapters of meaty urbanist details about housing and transit and land use at the heart of a book about superpower conflict and visions of America’s future, but…I dig it. I always learn a lot from reading Matt, especially on these topics. It’s a bit like reading Jared Diamond go on for 100 pages about varieties of domesticable plants — yes, I showed up to learn how Europe conquered the Americas, but botany is cool too!

What I really wished Matt would have done is provide more of a feel for what this densified, immigrant-packed, urbanized America would be like. What kind of house would I live in? How would I get to work? Would I be able to go see nature easily? Who would my neighbors be? Where would I keep my dog? And so on.

Vivid wordy descriptions would have been nice —Matt is really a data type of dude rather than a florid essayist — but I think even more powerful would have been pictures. I want to see what the One Billion America might look like.

Would it look like this?

Or this?

Or maybe this?

If we’re going to build a new country, we should be able to imagine it. That vivid vision must be left for another urbanist book.

A good idea that needs more exploring

Ultimately, Yglesias’ book succeeds at what it sets out to do — it injects an important new idea into the public consciousness. Simply uttering the words “one billion Americans” opens up possibilities and vistas that would otherwise go unthought. It’s a book that expands one’s mind about the possible.

But it leaves me wanting more. I want to know what this new, bigger America might look like. I want to know all the benefits we might derive from living in such an America — not just the power balance with China. I want to feel that vision, taste it, touch it. That would make it something worth not just thinking about, but fighting for as well.

In any case, go buy a copy of One Billion Americans if you don’t already have one. It’s the start of a long overdue conversation about this country’s destiny.

Noah, probably you know this already but there's one thing that people think immediately whenever anyone talks of migration: Reduced wages.

I think that the best way of getting people to come around to the counterintuitive idea that immigration doesn't reduce wages (and sometimes it can raise them!) is by asking people:

"When women entered the labor force, were men's wages cut IN HALF?"

Then let people wonder.

There's no better way of convincing someone of a counterintuitive concept but by trying to get them to think about how it works.

I bring this up because your idea about the need of visualizing this grand vision for America is right on-point. That's exactly what's necessary, specially with such a counterintuitive idea as this.

When it comes down to wages, the women-into-the-labor-force example is IMO perfect, because it's something that SOUNDS as if it should have reduced wages (it was a doubling of the labor force), but saying that it cut wages IN HALF would get anyone to pause and reconsider their priors.

The appeal of dramatically increasing the US population is not neatly geopolitical, in my view. It's also a way to shift and reframe domestic politics, including in ways that make the US more politically functional so that it can credibly rival China. Yglesias says some of this: the vision isn't just pro-immigration and pro-urban (things the left, mostly, wants), it's also pro-natalism/pro-family, which the right wants. What it means overall is that the US would not be *such* a rural country anymore. You can't keep the population of Wyoming so low if the population of the whole country is several hundred million more. And that solves a central problem: if there are large cities in Wyoming, the Dakotas, and Montana, if Ohio's cities are full of people again, then our political culture shifts. The US Senate is no longer the choke point.