Book Review: "Danger Zone"

Getting through the next 10 years of U.S.-China relations

I’ve been reading a lot of books about China lately. Most of these can be roughly categorized into two groups — backwards-looking books describing the economic, political, and social conditions that prevailed in China during the 2000s and 2010s, and forward-looking books about the possibility of geopolitical competition and conflict between China and the U.S. Both categories have been valuable.

Hal Brands and Michael Beckley’s Danger Zone: The Coming Conflict With China is definitely in the second category. The authors don’t spend a lot of time convincing you that China’s leaders are bent on conflict — that task was already carried out by earlier authors, such as Rush Doshi’s The Long Game. It’s no longer really a question of whether China intends to displace the U.S. as the world’s leading power — it does — but rather a question of how the U.S. and its allies can resist this attempt. That’s what Brands and Beckley try to answer.

Their basic argument is that China has long-term weaknesses that will ultimately put it in a weaker position relative to the U.S. They cite five weaknesses:

Population aging and population decline

Limited natural resources

Xi’s autocratic rule

Hardening geopolitical opposition

A slowing economy

According to Brands and Beckley, these long-term weaknesses mean China’s leaders see the writing on the wall. Realizing that their country is fast approaching the peak of its might relative to its rivals, Xi Jinping & co. have an incentive to strike now — to take Taiwan and the South China Sea, to displace the U.S. from its position of global importance, and to establish regional and possibly global hegemony. This would, they argue, be similar to the way Wilhelmine Germany eagerly embraced World War 1 out of fear that if they were to wait longer, Russia would industrialize fully and become too powerful for them to overcome.

To compound matters, the authors argue that the U.S.’ military modernization — which was undertaken to meet the Chinese threat — won’t bear fruit until the 2030s. So if China chooses this next decade to attack, the U.S. might be at maximum disadvantage.

This next decade, therefore, is the titular “Danger Zone”. They draw a historical parallel between the 2020s and the period from 1945 through 1953, when the U.S. scrambled to establish a stable balance of power with the Soviets. Drawing on those early Cold War years for inspiration, they recommend a raft of strategies to make it through this dangerous time. Among other things, these include:

Building an economic bloc that includes U.S. allies but partially excludes China, limiting China’s participation to lower-value goods

Building an overlapping system of alliances and partnerships that hardens opposition to Chinese expansionism

Gaining control of global technology standards

Denying China key technologies it needs

Protecting democracies against China’s attempts to encourage autocracy

Protecting Taiwan militarily

If these strategies succeed in preventing China from toppling the existing global order, Brands and Beckley argue, things will get a bit easier after that. China’s disadvantages — aging, resource limitations, etc. — will start to bite ever harder, just as the U.S. completes its military upgrade. After that, the authors foresee a less intense conflict that the U.S. and its allies are ultimately well-positioned (though far from guaranteed) to win.

This is a coherent, cogently argued case. It is far more measured in its conclusions, and rests them on a more solid foundation, than earlier books like The Hundred Year Marathon and Destined for War, while its policy recommendations are more actionable than The Long Game. Danger Zone therefore represents the maturation of the “China threat” series of books. It is a very good book, and you should read it if you’re at all concerned about these issues.

That said, I am not yet ready to accept all of the book’s conclusions at face value. As readers of this blog know, I am inherently skeptical of historical theories, and I would like to see them tested whenever possible. In this case, it should in principle be possible for someone with a good data set on historical conflicts to test the idea that countries are most inclined to launch aggressive wars when a long period of ascendance reaches a peak. I will suggest this to my friend Paul Poast. (Of course, the main competing hypothesis, the Thucydides Trap, also deserves to be similarly tested.)

It does, however, seem extremely prudent to worry about this. China’s approach toward its neighbors and toward the U.S. has become far more belligerent in recent years, and we don’t necessarily need a theory of conflict to tell that there’s the possibility of a war in the next decade. So it pays to be prepared. And many of the remedies Brands and Beckley suggest — especially building an economic bloc that excludes China, gathering allies, and maintaining technological leadership — seem eminently reasonable whether or not China’s leaders manage to frighten themselves into acts of aggression. The “danger zone” framing is a good one, and other analysts and scholars should be thinking hard about making it through the next decade.

At the same time, though, I feel like there’s a big piece of the puzzle that deserves a longer and more detailed treatment than Danger Zone gives it — the issue of longer-term economic competition with China.

Is China really headed for long-term decline?

The main conceit of Danger Zone is that now is China’s peak of power, relative to the U.S. and its friends and allies. This is the background reality that is supposedly pushing China toward conflict, but which will also put China at a long-term disadvantage if we make it past the 2020s.

But is it true? First, let’s talk about China’s demographic decline. This is very real — China is losing working-age population at the rate of millions per year, and that rate is set to accelerate. It is losing young workers even faster, and its old-age dependency ratio is rising quickly. Next year, it is project to see its total population shrink, even as India overtakes it as the world’s largest country.

But what Brands and Beckley believe is important — and what would presumably be key in a long-term Cold War — is not China’s absolute demographic decline, but its relative decline compared to its rivals. And the thing is that they’re all hitting demographic decline too:

This data set accepts China’s pre-pandemic official fertility rate number of 1.7, which would put it in the middle of the pack; in fact, the true number is lower. A Chinese government agency reported it at 1.3 in 2020, and the CIA puts it at 1.45. So China’s fertility is considerably lower than that of the U.S.

But it’s about the same as Japan, which is already considerably more aged. And it’s higher than Taiwan or South Korea. Meanwhile, U.S. fertility has plunged in the last few years and may have further to fall, while even India’s just went below the replacement rate. Demographic decline is just something that every modern society has to face; China’s is a little more severe than most, but it’s not dramatically more severe. If the U.S. continues to restrict immigration and/or becomes a less attractive place for immigrants to move, the difference will be even less significant.

And remember, China is starting out at an enormous population size advantage relative to every other country except India:

Thus, China’s demographic disadvantage seems likely to be a drag on its relative power, but not any sort of inevitable doom. In fact, it’s the U.S. and its allies that should be more worried about population disadvantage, and looking for ways to get more immigrants.

Second, Brands and Beckley talk about China’s slowing economy. This is also very real. China is in a recession now, but its growth — and even more crucially, its productivity growth — have been slowing for a decade now. For a variety of reasons, China’s rapid catch-up growth is probably permanently over.

But China’s economy is already vast in size. In GDP it doesn’t quite measure up to the U.S. and its allies, but in manufacturing capacity it matches them pretty closely:

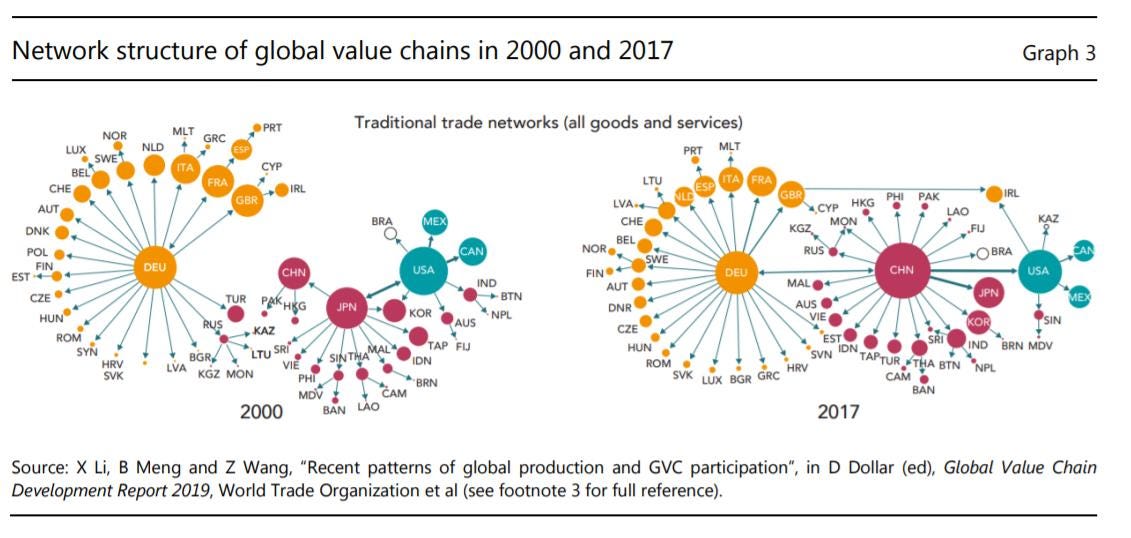

Nor is it at all clear that China’s percent of global manufacturing will wane in the future. Over the past two decades, China has established itself as what Damien Ma calls “the make-everything country” — the center of global networks of production and trade in manufactured goods:

The vast, impersonal forces of economic agglomeration — the tendency of producers, customers and suppliers to all locate near to each other in space — are pushing all of world manufacturing toward East Asia, and China is the center and by far the largest part of East Asia. In recent years, despite Trump’s trade war, China has only solidified its position as the center of global manufacturing, and multinational companies are finding it very hard to leave.

For the U.S. to replace the China-centered global manufacturing economy with one that even partially excludes China will thus be an incredibly uphill battle. That doesn’t mean it’s not a battle worth fighting, but it’s definitely not the kind of thing we can rely on happening on its own if we can just make it safely to 2030. Economically, China is no USSR.

Thus, while I think that thinking about the “danger zone” of the 2020s is very important, I think the outcome after that initial period will not be nearly as predestined as it was in Cold War 1. China is vastly more populous than the USSR, it is far more economically competent, and it occupies the center of the world’s manufacturing hub. Slowly declining demographics and the end of catch-up growth will not change that.

So I think we need to start thinking and planning now about how the U.S. and its allies can match Chinese power in the long term. Our job for the next 10 years is harder than it was in 1945, when we were the world’s unchallenged economic powerhouse, and all we needed to do was contain the Soviets militarily. This time, we’ll need to manage military containment at the same time that we start reshaping the U.S. economy and the global economy. That’s going to be a difficult task.

The "Thucydides Trap" implies that rival powers can't resist destructive escalation against each other. But that's an awfully selective reading of history, isn't it?

Sure, Britain and the USA fought in the War of 1812. Yet they never fought a war again afterward, not even once, even as the USA got stronger and stronger.

Sure, the USSR and the USA made opposite sides in the Cold War, and even proclaimed their wish to exterminate each other's philosophy. Yet they worked so hard to limit actual military conflict that even *other* countries' international wars after 1945 were actually much rarer than before WW2!

Are China and the USA fated to suspect and be nervous of each other? Sure, I'll buy that. But "nervous" can go two ways: escalation, or negotiation.

Some pairs of countries settled their rivalries by nervous escalation to all-out war, like Germany and Austria versus Russia in World War I. But other rivalries got eased by nervous negotiation that limited conflict, like USSR and USA in the Cold War. Not all "trapped" powers end up annihilating each other.

So, what's the best recipe for priming US-China tensions to head for "nervous negotiation" instead of "nervous escalation"?

Whatever that recipe is, it might be worth the world to find it.

Dear Noah Smith, I think your book review bring about all the key points that needed to be considered to understand China US relationship and where it is going between the two countries. However, I may not agree that China is threatening democracies. Mostly China's role in other countries have been economic dominance and China's involvement in local culture has been minimum and that is one of the reasons that most of the Chinese projects under belt road initiatives in South Asia, Middle East or Africa have not seen much progress. Neither China is assisting partner countries in technology transfer. All the good things of Chinese cooperation wiz a wiz economic cooperation is only concentrated to East Asia and probably that is the reason China is not allowing Taiwan and Hong Kong to break away. Both Taiwan and Hong Kong are the golden goose for China.

Secondly you conclude your blog with excellent points that is that China is dominating the global manufacturing supply chain and all multinationals are very comfortable with working in main land China. Thus it seems that Chinese belligerent behavior that is mostly concentrated to Taiwan and Hong Kong is the main threat to Chinese economic progress itself. For example, multinationals work very comfortably in Africa in diamond trade or oil, and those African countries are suffering from institutional underdevelopment. Multinationals have rarely contributed to institutional aspects like political stability or rule of law in the countries they operate and have relationship with the countries that offer some benefit to international trade with natural resources despite any challenges to local development or class conflict. Thus it seems that multinationals would keep working with China and would not expect China to improve its records on human rights. The introspection has to be done by CDC and President Xi as to transform its economic gains with better domestic governance. It is that Hong Kong and Taiwan has actually contributed to Chinese economic prosperity in its historic context, whereby both the East Asian cities are the global business hub that has brought the global supply chains to main land China. It is unfortunate that China is showing belligerent behavior towards both Hong Kong and Taiwan that btw is rejected by the citizens of both mega cities. Regarding American superiority over China, I should mention that the modern world is synonymous to brand USA and the American dream any where you go into the world. Yes there is economic competition of China and the US but there is no competition of US with China in practice of liberal values, cultural aesthetics, freedom of speech because these values are the future of the world a decade after or a century after. This reality should be known to any country that opposes US value system. Remember US is the country of immigrants and every person in this world is represented in the US economy and its prosperity. No country in the world other than may be Britain can claim this. So China and its leadership should know that there is only one way to progress and that is better governance that can implement modern values into the laws that the Chinese people abide by. Economic dominance is a different story and if China rejects modern values and democratic governance, future multinationals might not find it a consumer heaven as Tesla EV found by relocating its Giga Factor there.