The other day I wrote a Bloomberg post about Bitcoin mining and resource use. Some excerpts:

Many of the complaints about Bitcoin over the years have been overhyped. But the cryptocurrency’s increasing use of real physical resources — energy and computer chips — can no longer be ignored…

The higher the price of Bitcoin, the more valuable winning each little [mining] lottery becomes. And like an increased jackpot in Powerball, that bigger reward draws more miners into the game, who spend more resources making guesses. Those resources include computer chips and electricity to run the computers.

So the more Bitcoin’s price goes up, the more resources it consumes…Bitcoin mining now consumes electricity on par with the country of Finland…Meanwhile, Bitcoin’s demand for computer chips has hogged the production lines at Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. and Samsung Electronics Co., contributing to a global chip shortage…

For most financial assets, like gold, the cost of storage doesn’t go up much as the price goes up; it’s just about as easy to guard the world’s gold at $2,000 an ounce as at $200 an ounce…Bitcoin’s decentralized trust, in contrast, keeps getting more expensive as Bitcoin gets more valuable.

Blogger Nic Carter was kind enough to write a lengthy response, in which he downplays many of my concerns. I am grateful that the title of his post — “Noahbjectivity on Bitcoin Mining” doesn’t leave out the second syllable of my name when making a pun. I can’t tell you how tired I am of people saying stuff like “Noahbrain”, as if the “ah” just doesn’t exist! So thanks, Nic, for making an actually good Noah pun.

But before I address Nic’s arguments, let me point out that while I’m not objective, I am certainly not ideologically biased against Bitcoin. I am long BTC! If Bitcoin appreciates I will make money. Also, a lot of Japanese people own a lot of Bitcoin, and I want them to make money too, since Japan’s economy needs a boost. So I want Bitcoin to go up! My article was written NOT from a standpoint of “Bitcoin is bad and we should ban it”, but rather, “Here is what Bitcoin should do in order to keep the party going.”

Anyway, on to Nic’s arguments!

Gold and resource consumption

Nic points out — correctly — that Bitcoin is far from the only asset whose extraction consumes more resources as its price increases. He posts the following graph for gold:

Theoretically this is true for stocks as well; raise the price of equity, and theoretically you should draw new companies into the market, which increases the amount of real resources devoted to creating new companies. And if the price of houses goes up, people put more resources into homebuilding.

But remember that extraction is different than storage. For Bitcoin, extraction and storage are the same activity — mining both creates new Bitcoin and verifies the existing blockchain. Verifying the existing blockchain is the way Bitcoin is stored.

But for most assets, these are different activities. For gold, the cost of pulling it out of the ground is completely decoupled from the cost of guarding it in a vault. For houses, no one can steal your house, but the storage cost is the maintenance you have to do on the house to make it keep its value. For stocks, the storage cost is the spending a company has to do in order to maintain its earnings — investing to balance out depreciation, fending off competitors, and so on. And for any currency stored digitally, a storage cost is the cost of digital security — keeping out hackers, identity thieves, and so on.

For most of these assets, storage costs do probably go up somewhat as the price goes up. The more expensive gold is, the harder thieves will try to get into your vault, and the more guards you’ll have to hire. For stocks, the higher equity prices are, the more companies theoretically have to spend fending off competitive attacks from new market entrants. For digitally stored assets, the more valuable the assets, the harder hackers and identity thieves might try to get at them. (Housing might be an interesting exception, since the resource cost of home maintenance should be decoupled entirely from the price, except perhaps through economic effects like home prices driving up local wages.)

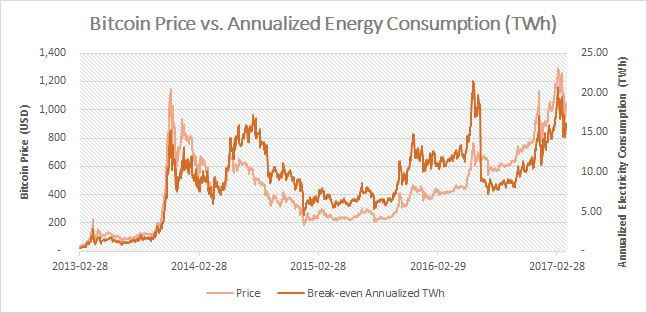

But for Bitcoin, the resource cost of storage theoretically increases as a more-or-less linear function of price. Here, via the excellent blog Digiconomist, is a derived upper bound on Bitcoin electricity usage as a function of the cryptocurrency’s price:

Of course, that’s an upper bound; the lower bound will increase more slowly, though Digiconomist cites data showing that real-world mining is well above the lower bound.

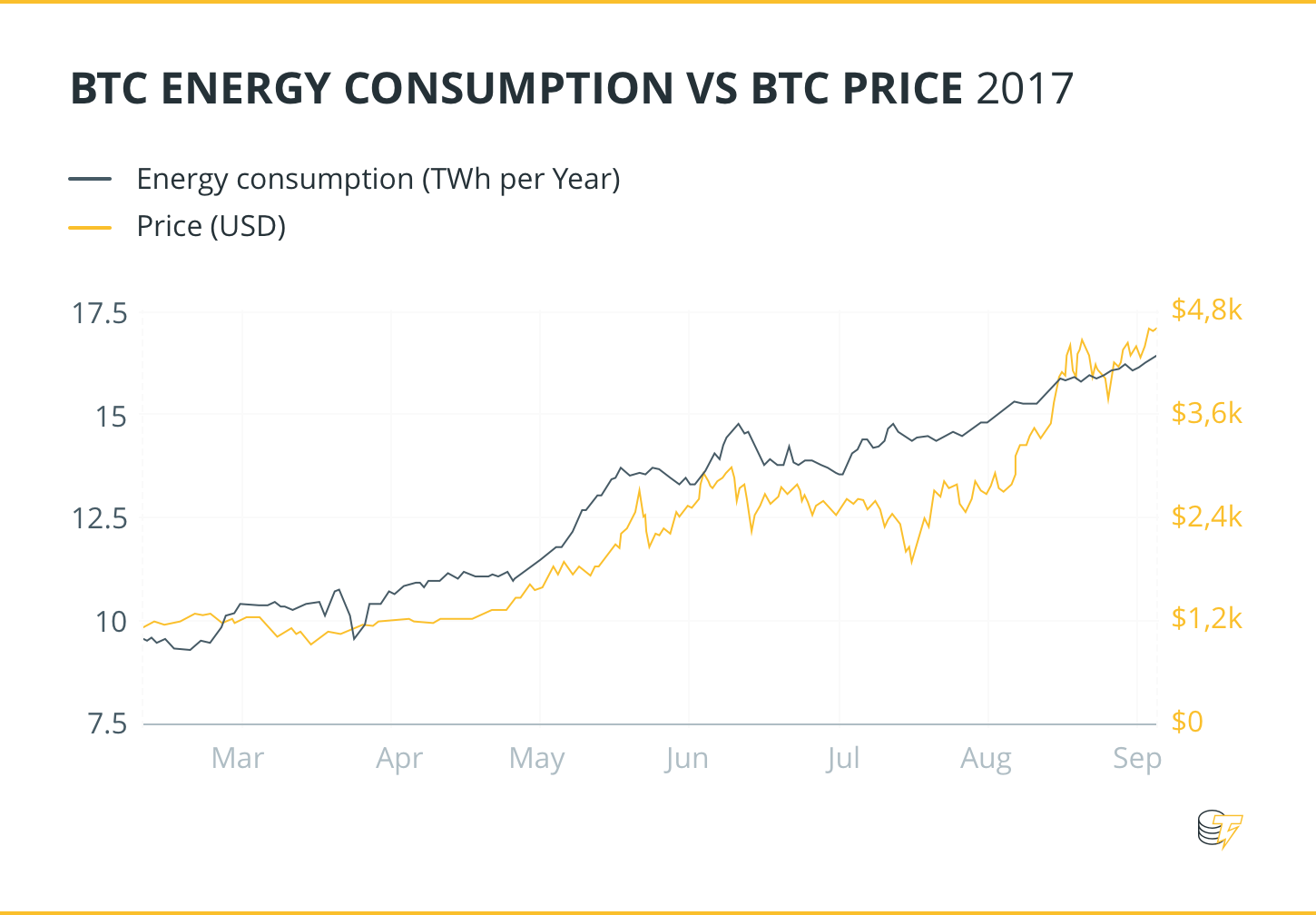

Here’s some data from Cointelegraph (originally collected by Alex DeVries). During 2017, energy usage more or less tracked price:

But during 2018, energy use continued to expand even though price fell:

So this is actually faster than a linear function of price.

That’s just not a very efficient storage technology! Gold has clear economies of scale in storage — you might beef up security a bit if gold’s price quadruples as it did in the 2000s and early 2010s, since thieves might take more of an interest in gold, but probably not too big of a change, since you’re still guarding the same physical space.

The same is true of other assets. Housing maintenance costs don’t even really increase much as house prices go up. Theoretically, high stock prices should require more investment spending to fend off competitors, but in reality as stock prices have steadily risen we’ve seen flat or declining investment and decreased competition, so theory is sort of breaking down there. IT security spending on digital assets doesn’t really seem to depend much on asset prices at all, but rather jumps around based on other factors like banks shifting to digital infrastructure. (Note that Bitcoin security spending isn’t all blockchain spending, by the way; companies like Coinbase also have to spend on IT security. But let’s ignore that for now.)

In other words, if we want or expect Bitcoin to maintain anything close to its recent meteoric price growth, storage costs — i.e., the energy and chip costs of Bitcoin mining — are going to become a bigger and bigger issue at a correspondingly meteoric pace.

Stranded energy and chip production

Nic writes that Bitcoin miners can get around the electricity usage problem by finding sources of stranded electricity — electrical power generation that’s going to waste, usually because of intermittency, but also because of various sources of waste. In fact, this is a good approach, and I wrote a whole post about it back in January. I wrote:

So if you’re not going to store it, what do you do with all that extra solar electricity during the sunny times? One thing you could do is to use it to mine Bitcoin. That will make some money for the utility company, which it can then use to recoup some of the cost of building the solar plant in the first place.

In other words, using extra solar peak capacity for BTC-mining could make solar a better financial proposition for a utility in the first place. And that could speed the transition away from fossil fuels. When the World Economic Forum called Bitcoin “energy storage”, this is what it actually meant.

As I note in my original post, however, this is a stopgap measure. Eventually you run out of stranded energy assets that producers are willing or able to let you exploit. And since total energy usage in the world is increasing much more slowly than Bitcoin’s price, this puts you up against a hard limit eventually.

In fact this may be happening already. Nic repeatedly cites China’s province of Inner Mongolia as a place where there’s plenty of stranded energy available for mining, but as Nic notes, Inner Mongolia just banned Bitcoin mining entirely. The stated reason is to meet clean air goals (Inner Mongolia’s power comes mostly from coal), but even places with cleaner energy will eventually find their systems overburdened if Bitcoin’s price keeps soaring up and up. Towns in Washington State are trying to clamp down on Bitcoin mining because mining is overwhelming local grids; according to Politico, these towns often find themselves waging “guerrilla warfare” against miners trying to siphon electricity illegally.

Those articles were written when Bitcoin was at $41,000. It’s now at $59,000. Imagine what will happen to towns’ local electrical grids at $500,000. Just doing this simple thought experiment shows what a short-term stopgap measures like the ones Nic discusses really are. Yes, it’s good to look around for stranded electricity, but if Bitcoin’s price appreciates at anything like the rate of recent years, the simple numerical inadequacy of that approach will make itself known.

As for chips, Nic makes the useful point that GPUs — which are the focus of the recent chip shortage — are used to mine Ethereum, while Bitcoin is mind with a different kind of chip called an ASIC. And he notes that TSMC gets only 1% of its revenue from Bitcoin miners. So Bitcoin chip production is not a huge problem yet.

But again, think about the future. As price goes up, that 1% will rise. And TSMC’s production resources are fungible; if the company diverts more of its workers and machines to making ASICs, that’s fewer resources for everything else in the economy. That will increase pressure on TSMC (and other manufacturers) to limit the amount of resources they devote to Bitcoin-specific chips.

In fact, Nic points out a way that NVIDIA is already doing this with GPUs:

Interestingly, NVIDIA is aware of this problem, and has built a crypto-specific GPU, while building in anti-mining mechanisms in their mainstream GPUs. The general purpose GPUs will throttle usage if they detect crypto mining activity. This is a very smart way to segregate their product lines across different customer segments and solves the problem of miners pricing out gamers and other GPU consumers.

This intentional segmenting of its chip products means NVIDIA is already worried about miners hogging resources from everyone else. There’s no reason to expect TSMC or other foundries to be any different.

And again, think to the future. If NVIDIA is doing this with GPUs today, imagine what companies will do when Bitcoin’s price goes up 1000% from where it is now. This is worth thinking about and preparing for.

Seeking a blue-sky future for Bitcoin

Mining bans and chip limitations won’t kill Bitcoin, but eventually they could drive up the price of mining substantially. As Bitcoin’s price soars, more jurisdictions will probably limit or ban mining, and more chip companies will find ways to limit the amount of resources they commit to making chips for miners. That will squeeze miners into a shrinking number of jurisdictions and either ration their compute resources or force them to turn to inferior products from producers like China’s SMIC. That’s not a death blow for Bitcoin, but it’s not good.

That’s why in my original post, I suggested a technological solution: fork Bitcoin, and have a new version that uses a storage technology that doesn’t scale linearly with price. I suggested Proof of Stake as one potential alternative, because it’s the one most people have heard about. Nic disparages Proof of Stake on ideological grounds — it’s more centralized than Proof of Work. He also disparages other alternatives, such as Gridcoin (which uses Proof of Work calculations for other useful purposes), on similar ideological grounds. I have no doubt that the same ideological opposition would apply to other alternatives that people have suggested, such as directed acyclic graphs or second-layer solutions.

And indeed, if you really care about the ideology of cryptocurrency, this is a big drawback. But as resource use spirals and constraints multiply, it might be necessary to compromise on ideology. Again, to reiterate, this is all about the future. Lack of economies of scale in storage of an asset represents a real technological weakness, and there are clear signs that local governments and chip producers are already seeing the writing on the wall. If Bitcoin’s price continues to skyrocket — as all Bitcoin hodlers should want it to! — then the day is not far distant when the inherent resource-intensiveness of Bitcoin will become a severe problem. So it pays to think now about what to do if and when this happens.

You describe the chip supply food-fight as occurring between miners and gamers, but actually, GPUs are used to train deep networks for almost any application you can think of. Have you seen , say from NVIDIA, any breakdown of where the world's supply of GPUs is going? I seriously doubt that gamers are still such a big component.

Wait I thought there is a hard cap on the number of bitcoins that can be mined, and that we are nearing the end. Does energy intensiveness remain a problem once there’s no more BTC to mine?